"Time doesn't exist when you're... just chilling!" Topping an administrative page on the site of curatorial collective Jstchillin, this slogan rephrases a familiar bit of folk phenomenology: Time flies when you're having fun! But in denying time's existence, rather making its perceived acceleration a metaphor for losing yourself in the moment, the slogan suggests a swap of the trinity of past-present-future for something else -- a sense of time that (until the end of this essay, at least) I will call "chill time." Jstchillin is concerned with the internet, and my description of chill time will be, too. It entails an awareness of parallel threads of messages, ordered by clock-time sequence and subjective assignments of importance (cf. Facebook's feed settings: "Top News" and "Most Recent"), and the knowledge that these messages will wait until you find them (in your e-mail, in your RSS aggregator, etc.) but might be irrelevant when you do if you wait too long. Chill time is simultaneity of the recent past and lagging present, the sum of attempts to track some threads into the past and push others toward the future. Awareness of physical surroundings tends to be fuzzy as you sift through old layers of digital sediment and deposit new ones. Jstchillin founders Caitlyn Denny and Parker Ito describe it like this: "[T]o chill is to live in a constant state of multiplicities, a flow of existence between web and physicality."

Jstchillin encompasses a number of initiatives, including the gallery show "Avatar 4D," but its flagship project is "Serial Chillers in Paradise," an online exhibition that has featured a different artist every other week since October 2009. Chill time, I think, is the central theme of "Serial Chillers," one that many commissioned artists have approached through conventional associations with chilling. Video games were the subject of an illustrated short story/film treatment by Jon Rafman, and Jonathan Vingiano's browser add-on Space Chillers was a game. Ida Lehtonen's contribution folded soothing ocean sounds into a video of exercises that computer laborers can do to stay limber during breaks, while Eilis Mcdonald's sent you scrolling through bits of pat, New-Agey advice and then to a page with equivalent visuals; both artists drew on packaged relaxation. Zach Schipko and Tucker Bennett's feature-length movie Why Are You Weird?, parceled into YouTube uploads, is a story of art-school students who spend almost all of their onscreen time at parties or hanging out in their dorm rooms, rehashing crits.

There is more to "Serial Chillers," of course, than web sites about fun stuff, and Denny and Ito try to communicate as much in their manifesto by citing Proust ("real without being actual, ideal without being abstract") alongside extreme chatspeak ("If ur lukin 2 meet nu frndz, enemies or if ur lukin 2 ave fun, herz d plce 4 ya."). The self-effacing attitude of Jstchillin seems partly indebted to the surfing clubs that flourished from 2006 to 2009, to use Tom Moody's historical brackets. But those group blogs gave a more convincing impression of effortlessness (even if savvier viewers appreciated the extent of research involved); the top-down organization and meticulous calendar of "Serial Chillers," not to mention the scope and size of each project for it, can't hide the technical expertise or consideration invested in it. The underachiever attitude is a compensatory measure, one to support Denny and Ito's exclamation: "[W]e are the slackers of the art world!"

If self-awareness is key to Jstchillin's conceptual structure, it stems from awareness-enhancement as an artistic device -- the use of art's frame to sharpen the perception of elements that go unnoticed in life. Recent history's acts of conceptual chilling -- The Act of Drinking Beer with Friends Is the Highest Form of Art, and Rirkrit Tiravanija's soup dinners, among others -- frame social interaction. Of the many possible online analogies for this, you could cite early projects for "Serial Chillers" by Mitch Trale and Cody Blanchard, with shifting visual environments that track the movement of your mouse, vividly visualizing mechanisms of the interface. While Marioni, Tiravanija and the like operate within limits of time -- a gallery's hours of operation, an exhibition's run -- a web site is what you want, when you want it. Trale and Blanchard's projects will keep doing what they do indefinitely. Other artists harness this aspect of chill time by using loops and options, like Lehtonen's aforementioned exercise routines, and Ivan Gaytan's menu that calls up windows of visual and sonic noise.

Internet art has sometimes been described as "performance" because of the potential for development over time, and while that may be useful to some extent, I think it relies too heavily on a vague common notion of what "performance" is. The study of language might offer more specific terms. Roman Jakobson's 1960 essay "Linguistics and Poetics" names six functions of language that all operate in any act of communication even as one dominates. An utterance like "Can you hear me?" affirms that the channel of communication is open; its primary function is what Jakobson called the phatic. He took this term from anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski, who introduced it in the 1920s in his studies of small talk. Jakobson and Malinowski discussed two aspects of the same purpose -- confirming contact -- though Jakobson was more concerned with speech establishing the physical possibility of communication (again, "Can you hear me?"), while Malinowski was interested in the social possibility ("How are you?", "Nice weather we're having," etc.).

"Hello?" confirms a working connection at the beginning of conversation over the telephone. The internet started out in phone lines and expanded their potential as vehicles for communication, effectively spawning millions of ways to say "Hello?" -- from "A/S/L" in AOL chat rooms to tweets documenting the contents of the tweeter's lunch. The latter barely count as vehicles of information; mostly, they are there to remind the tweeter's network of his existence, reaffirming the connection among them. The phatic function dominates online language in professional media as much as social media, as outlets produce more news to stay on top of the non-stop news cycle, reminding readers of the brand's presence.

Gareth Spor's contribution to "Serial Chillers" directs you to a video chat with a NASA space station. It singles out the idea of contact through exaggeration and extremity, by selecting a channel of communication that spans the void of outer space. Guthrie Lonergan shows a bigger concern with the social conditions of contact in 3D Warehouse, a collection of Google Sketchup drawings of objects seen in dreams, accompanied by verbal accounts of those dreams. The sharing of dreams is an odd kind of small talk, as meaningless as discussions of weather but more intimate, something you'd only do with a close friend. But the Google Sketchup users in Lonergan's collection put their dreams out there for anyone. The discomfort you feel from this distortion of social convention is reflected in the images, which -- for all the modeling skills of the artists who drew them -- are awkward and cartoonish, thin shadows of a stranger's dreams. I brought up both Lonergan and Spor's projects to demonstrate the importance of the idea of the phatic function to this discussion of "Serial Chillers," but I would say that Lonergan's project is the more memorable of the two, both for the emotional impact he achieved by touching his audience's unconscious knowledge of social norms and for the use of text. Writing is a technology invented to transcend time by superseding the immediacy of speech, but the internet puts it at the service of the phatic function, which is all about immediacy and presence. This paradox is a big part of what produces the effect of chill time.

While a message in a Twitter account, a blog, or a professional news service may have little apparent use beyond the present, the quantity and frequency of messages give the message's sender authority. Their sum is an online artifact, a fossilized yet living piece of chill time, and the size of it indicates its potential usefulness for a searcher in the present digging something out of the past. The accumulation of past moments in a present entity is somewhat like the design mechanism of video games. The protagonist accrues experience and equipment over many hours of play -- interrupted by pauses, "deaths," etc. -- that determine his chances of defeating an enemy at any given moment in the present. In "Serial Chillers," this sense of chill time is perhaps best articulated in Watching Martin Kohout. A YouTube channel documenting Kohout's viewing of YouTube videos, it is more affecting than a Favorites list as a record of the act of viewing. Rather than being an index asserting each video's potential for viewing enjoyment, it captures the present time of each of those connections and collects them for another, future present.

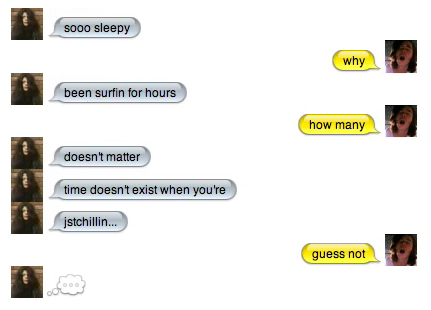

"Serial Chillers" was announced with an IM screenshot, a fragment of a bigger chat between Jstchillin's founders -- and this set the tone for the whole project. While Denny and Ito share philosophical precepts with their peers in the net-art world ("It is important to keep in mind that the concept is identical to the object," they write), their focus on chill time sets Jstchillin apart from other web-based curatorial initiatives. Netmares & Netdreams was about creative perception of things seen online, employing dreams as a metaphor for the internet's uncertain reality. Club Internet, with its guerilla curatorial philosophy and hidden or deleted past, is about looseness of location, transfer and transience. Nasty Nets and dump.fm touch the issue of chill time by adapting its form. "Serial Chillers" makes it the subject.

Yo BD, I'm really happy for you Imma let you finish, but Ben Vickers had one of the best JstChillin projects of ALL TIME!!!

JstChillin is most certainly my favorite of Ito and Denny's projects, but it seems their/your idea of "Chill Time" borrow an awwwwful lot from Cory Arcangel's idea of Continuous Partial Awareness. Perhaps it's a battle of semantics, perhaps it's just an ideological re-blog.

This seems way off. Please explain.

Nevermind, I went to your website.

Or perhaps we chilled too hard and got lazy to think of our own thing and just stole his shit?

Ceci mentioned Continual Partial Awareness after she read my draft, so I've been thinking about it a bit over the past two days. For one thing, Continual Partial Awareness (as I saw it performed) was a Powerpoint presentation of fifty unrealized ideas. "Serial Chillers" is like what would happen if you took those ideas and made a web page/netart project about each one and released them every other week for a couple of years. Cory Arcangel's performance was an attempt to replicate and mimic the online experience of time, whereas "Serial Chillers" is a slower and more aloof consideration of it. In that respect, the difference between the two is like the distinction between form and subject I introduced in the last two sentences of the essay.

Even if that was the only difference, I'm not sure citing Cory Arcangel would be necessary – after all, he's not the first person to point out that computers let you do several things at once (I mean, he could have titled his piece "Multitasking!") or that doing so makes you feel kind of distracted and stretched thin. But there are more bigger differences, too. Among other things, "Serial Chillers in Paradise" is an extended survey of the internet's possibilities as a time-based medium. What sets it apart from video or performance isn't just the availability of menus and loops (database vs. narrative, as Lev Manovich put it). It's also what happens when Guthrie Lonergan tries to make a durable document by probing ephemeral messages, or when Martin Kohout takes the amorphous YouTube surf sesh and divides it up into discrete units recorded over the course of several months. The context built by Jstchillin brings this to the foreground, through the lens of chillin. Continual Partial Awareness doesn't have anything to do with that.

I would also like to say that I have absolutely no desire for "chill time" to become a Term. I needed some short-hand to refer back to the condition described in the first paragraph, something brief and not-too-pretentious that communicated a sense of solidarity with the artists. Chill time fit the bill at the time, and now it's disposable.

Too late, "chill time" is a term.

[img]http://img.photobucket.com/albums/v90/oatsuzn/fantasia.gif[/img]

*Shipko

I enjoy Rider Ripps' piece on Just Chilling