The stage at St. Petersburg's Sergey Kuryokhin Modern Art Center was set for a blast of live electronic music, with seating for ten performers, each station equipped with samplers, laptops, and electric guitars. As the audience arrived the musicians tinkered with the controls; one stood near a huge glass jug, adjusting wires submerged in its murky liquid. But when the appointed time for the concert's start arrived, the performers retreated to the wings, and recorded music came up and continued for the next twenty minutes. It seemed almost like a wry comment on the detachment of the physical presence of the performer from the source of sound in electronic music. But in fact it was an unannounced presentation of past issues of Tellus, the 1980s journal of experimental sound produced by Harvestworks, selected by director Carol Parkinson. As it faded, the musicians took their places, at last, to perform Third Eye Orchestra, a piece written and conducted by Hans Tammen. It was a controlled improvisation, where Tammen lifted numbered cards indicating which of the score's instructions should be read at that moment. The musicians, all local recruits, visibly relished both the spontaneity and the monstrously loud sound that only an ensemble of many amplified electronic instruments can produce.

The Harvestworks evening was part of the program of the third edition of Cyberfest, an annual festival conceived and organized by Anna Frants, a New York-based artist and gallerist, Marina Koldobskaya, director of the St. Petersburg branch of Russia's National Center for Contemporary Art. The NCCA hasn't had a building in St. Petersburg since the branch was established six years ago--a problem played up the first night of the festival, when a new Cyland museum in Second Life was presented--and so the concerts and presentations took place in venues around the city. The festival's climactic event was a performance by Paul Miller, aka DJ Spooky, at the Hermitage Theater, a marble-studded auditorium built for Catherine the Great's private entertainment. Miller added a soundtrack to Dziga Vertov's 1924 film Kino-Glaz that he planned roughly in advanced but mixed live. Originally, the silent film was accompanied by live orchestras improvising arrangements of popular tunes of the day, but that wasn't Miller's primary concern. Rather, his project illustrates the already well-established connection between contemporary remix culture and the editing experiments of Soviet directors like Vertov and Sergei Eisenstein. His dance rhythms homogenized the haphazard sequence of Vertov's attempt at presenting reality; the lush sound and the virtuosic mixing brought a surfeit of dramatic expression to footage that Vertov prized for its plainness. The gap between film and soundtrack reduced Kino-Glaz to an exotic backdrop for a display of DJ skill rather than engaging it in counterpoint.

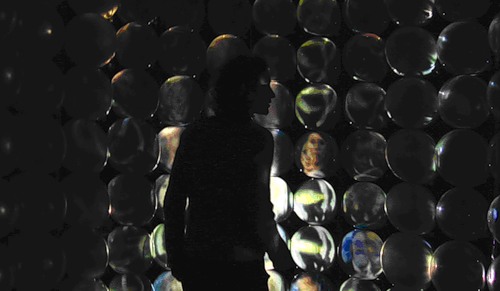

Kino-Pravda, another Vertov film, was played with Miller's music in a three-channel installation at the Manege, one of the exhibition sites for Cyberfest. That show also included Sergey Kotsun's Orchestrion, a screen with a two-dimensional, Nintendo landscape that bloomed with trees, clouds, and stylized floral patterns in response to the viewer's motion, and Nikita Tsymbal's installation Paralleloid, where the pendulous swings of a ball hanging in the room's center affected the intensity of the vibrations of black and white stripes projected on the wall. Alexandra Dementieva reconstructed her 2007 project Alien Space. The walls of its zig-zagging corridor were made of white balloons, which at the center held talking heads of anchors delivering news in sixty-seven languages. Depending on a body's position in the space, all but one voice would fall silent, and thus it turned the viewer into a human tuner in search of a familiar code. Behind it, eight slide projectors clicked to the rhythms of the first movement of Brahms' Double Concerto, as they flashed photographs of twenty years of exhibitions in St. Petersburg, a low-tech virtual museum of sorts to complement the one in Second Life. The system was credited to Frants, the concept of the content to Koldobskaya--a chance for the festival's directors to have their say.

In fact, several works both at the Manege and at Cyberfest's other exhibition venue, the education center of the Hermitage Museum, were credited in part to Frants and Koldobskaya. For the most part these repeated well-worn concepts from the media art arsenal: a choreography of images to sound (such as the Act or a Symphony for 8 Slide Projectors, described above), a headset that transports the wearer to another reality, and robots that react to audience movement. This might be explained either by the festival's pedagogical mission, or the relative paucity of artists engaging technology in St. Petersburg. But one also got the impression that the organizers neglected to take full advantage of available local resources. Whitney curator Chrissy Iles was in town to give a lecture on the history of video art at Pro Arte Institute in connection with the opening of a Rufus Corporation exhibition there; that might have made an interesting counterpoint to the lecture about the few Soviet counterparts by the director of the Prometheus Institute, who presented digitized versions of synaesthetic films by Bulat Galeev from the 1970s and '80s. Perpetual Art Machine, an artist-run online video-art database, came from New York, but Moscow's MediaArtLab, a comprehensive archive of Russian video, had no presence; there weren't even any Moscow-based artists working in related fields, such as Dmitry and Elena Kawarga. Koldobskaya might have invited her colleague Dmitry Bulatov, a curator at the Kaliningrad branch of the NCCA who recently completed an anthology of documentary films on biotech design, or Alexander Efremov, a Petersburg-based geneticist who has recently collaborated with artists in his laboratory. Such science-based practices would not have been entirely out of place, given the festival's loose usage of the cyber- prefix. The third edition of Cyberfest demonstrated the organizers' ability to make some interesting juxtapositions of ideas and involve a number of venues and organizations, but future endeavors will require more focus to convince its audience, both local and international, why "cyberart" and the Cyberfest itself matter now.

Perpetual Art Machine will be partnering with Media Art Lab in the coming months.

PAM 2.0 is in the works, so stay tuned.