The latest in a series of interviews with artists who have a significant body of work that makes use of or responds to network culture and digital technologies.

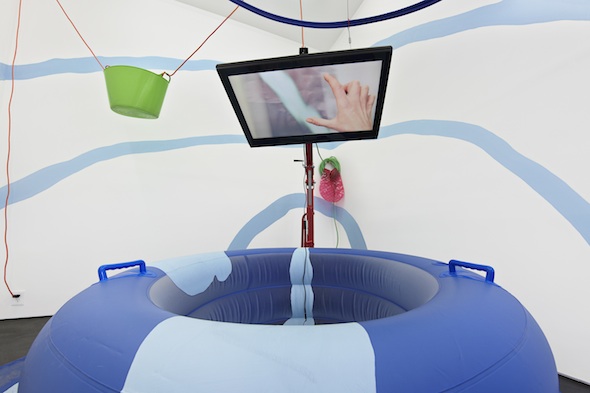

Heather Phillipson, immediately and for a short time balloons weapons too-tight clothing worries of all kinds (2014). Image courtesy the artist and Bunker259.

When I saw your recent solo exhibition, immediately and for a short time balloons weapons too-tight clothing worries of all kinds, at Bunker259, I curled up in an inflatable birthing pool to watch a video suspended from an engine hoist. The video depicted a series of domestic, public, and online spaces, with a voiceover from you. At one point, you leaned over the camera and appeared to give me a facial. I broke down in laughter because it suddenly became clear that I had become a participant. When you show Zero-Point Garbage Matte, you use a similar strategy: the viewer climbs up a ladder and looks down on the monitor to view the video, a position that is reflected in its content. Which idea comes first, the video or the physical participation of the viewer?

The video usually precedes its final sculptural form, but not always. With the video suite I'm working on at the moment, for example, I have a really clear idea of what will be going on around it. Regardless, I produce multiple "versions" of each installation, so the video ends up inhabiting quite different physical structures at different times. It's like a built-in contrariness mechanism—the capacity to change the context, and therefore the work, and my mind. But, in general, the one constant is how the viewer is con/figured in relation to the video. So, with immediately and for a short time balloons weapons too-tight clothing worries of all kinds, as you mention, the viewer is recumbent with the video overhead. The video deploys regular POV shots alongside dispassionate observations, and mixes interior monologue with direct address, so there are these shifting perspectives. You're the eye/I of the camera, or its eye is turned on you…positions get conflated. For me, the physical relationship between body and screen is crucial to this formulation, although the rationale might only be revealed sporadically. It's a bastardised literary device, that semblance of inhabitation and activation—one minute you're in first person then second person or third person, then slapped back into first.

In terms of process, I think of it like a temporal collage or a physical musical composition—whether it's video editing or writing or walking between things in space, it's about the rhythm between the bits. And the bits are always colliding with or repelling or rubbing all over each other, synaesthetically. Structurally, the sculptural installations might be like arriving in the middle of a poem, not knowing what's going on, but understanding it—all these metaphors, line-breaks and non-sequiturs. I'm trying to establish an equivalence, I suppose—a kind of syntax of sounds, images, colours—using them like parts of speech. And it's deliberately non-hierarchical, so it's not that words precede images or images precede sounds—they spark off each other. Their relative status is confused.

Heather Phillipson, THE ORIGINAL EROGENOUS ZONE, with Rowing Projects at Art Brussels (2014). Image courtesy the artist.

Let's talk about rotten potatoes and watermelons. Your video installations often include organic elements, like fruit and vegetables, which decay over time. What do you see as the significance of these materials? Do you replace them throughout the exhibition or do you let them die?

With THE ORIGINAL EROGENOUS ZONE, I was thinking of the entire environment as being the video, exploded. How the video might feel if you were to walk through it. Then, with all these tactile references, with chunks of the video jutting into the space around it, there's a point at which the digital image and the experience of it start to cross over. The video becomes a place. The fruit and veg are an important part of this. Everything is there for multiple reasons—visual, metaphorical, functional… Of course, there's an obvious euphemistic element to the potatoes and the watermelons—like the potato bags sagging from a bent tap (PRIVATE PARTS PICTURES PRESENTS), or with a battered cardboard palm tree thrusting out of them (Roman Classic Surprise)—because the video is constantly confusing sex and language, food and speech. There's this recurring motif of the mouth as a portal for eroticism and intellect so there's a deliberate confusion of the human and vegetal body-parts in space too, like 3D nouns. Plus, obviously, we know all these bodies are rotting, regardless of literally seeing it.

Whether, or how soon, they're replaced in the exhibition depends on the circumstances. Last year, in an exhibition I had at Zabludowicz Collection, I made an upturned dining table with a shelf, on which I stuck that classic Christmas dinner party trick (well, at my table anyway)—a satsuma peeled into the shape of a dick. That one I allowed to really shrivel up until it was about half the original size—a pathetic, dried out, dying thing. Similarly, I wanted those potatoes on the bath to start sprouting in their bags, pushing out their hairy shoots, eventually leaking and dripping onto the floor. But then, with the watermelons, there's an additional utilitarian aspect—they're used as ballast to weight the bathtub to the floor. They really need to stay ripe because it's part of their buoyancy. So everything's in varying states of decomposition. And all these bits (bodies) provide something qualitatively different to the monitor and electronics. They have a different life, different textures. Textural differences are really important in the work—constant shifts between surfaces, qualities, modes of touching...

Heather Phillipson, ha!ah!, installation view at "yes, surprising is existence in the post-vegetal cosmorama," BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, UK (2013). Image courtesy the artist and Colin Davison.

Your voice creates a consistent, comforting tone in your videos. You have this particular deadpan delivery that sometimes comes across as humorous and other times dark, depending on how it's combined with the images. What do you think the voice contributes to these pieces?

The videos constantly switch tones and materials (HD, SD, vivid, degraded, "natural" sounds and images, manufactured sounds and images, hijacked sounds and images)—the voice is the glue that holds them together. It's on the surface and underneath and in between. I want it to have the veneer of this impartial, seemingly stable material while, around it, or without it, parts threaten to get out of control. And maybe this is where something that sounds authoritative or personal or reassuring starts to become suspicious—some line between ease and dis-ease. For me, it has something to do with intimacy—the appearance of admittance or proximity vs what's made accessible. Which in turn relates back to the physical place that you and the video occupy. It starts to raise questions—in my mind—about what that relationship is to the/a work, to things, people—how close we're allowed to get—virtually and actually.

But the straightforward answer is that it's my voice—there's not much I can do about it. I'm interested in that—the self that's always ex-pressing, dribbling out, whether we like it or not—what our bodies give away.

You once told me something I'll never forget: "I'm a poet because I want to spend five hours writing three words." Can you describe your relationship to language?

It's not easy.

Questionnaire:

Age: 35

Location: London, UK

Where did you go to school? What did you study? UWIC / Central St Martins / Middlesex—art & aesthetics / drawing / fine art

What do you do for a living or what occupations have you held previously? Artist, poet—many other necessary money-earners, most of which I'd rather forget.

Which artists have influenced you the most, or which projects? That's tough—so I'm going to reel off some great, bold women who have pepped me up along the years—Sturtevant's omnivorousness, Rosemary Tonks' brittle inter-/outer-self-voyages, Bonnie Camplin's wild advice-nuggets, Julia Heyward's language torturing, Kathy Acker's hard lines, Phyllida Barlow's place and mind-filling, Susan Sontag's on-the-nose-ness, Virginia Woolf's everything, Christine Brooke-Rose's interior death monologues, Sister Corita's polemics on cardboard, Keren Cytter's structure-shaking, Agnes Varda's lo-fi touchy-ness, Joan Jonas' ongoing multi-layers, Claire Denis' brutal truths plus momentary pop music simplicity, Marianne Moore's tricorn hat-wearing, Salt-n-Pepa's early riffs, ferociousness, under-cuts and hi-tops—I'm really just getting going...

What does your desktop or workspace look like? my head, inside-out

Interview conducted in person in London, July 2014.