(Courtesy the artist and Taxter and Spengemann Gallery, New York, NY)

Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Grey upset the purpose of portraiture--rather than preserving the memory of its subject in his best light, the painting of the title grew gradually uglier to record Grey's sins, even as he kept the beauty that facilitated his sinning--but left intact art's status as an attribute of rich, leisured living. The arch moral tale is invoked twice in "Virtuoso Illusion: Cross-Dressing and the New Media Avant-Garde," an exhibition currently on view at MIT's List Visual Arts Center. Michelle Handelman's hour-long, four-channel video Dorian, 2009, loosely retells Wilde's novel with club kids standing in for opium eaters. In her ghoulishly lit self-portrait Dorian Grey, Manon appears messily caked in makeup, wearing a baggy gray suit, like the corporate conscience of a hedonist spirit. Both of these works introduce to drag a story about beauty, representation, and pleasure, and the anxieties that attend them. This suggests there's more to "Virtuoso Illusion" than an exercise in gender studies; as exhibition curator Michael Rush writes, "[i]n each major historical advancement of experimental art, cross dressing has been present as a strategy that has expanded the possibilities of the perception-bending intentions of artists (as opposed to merely gender-bending)."

(Copyright Matthew Barney. Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York.)

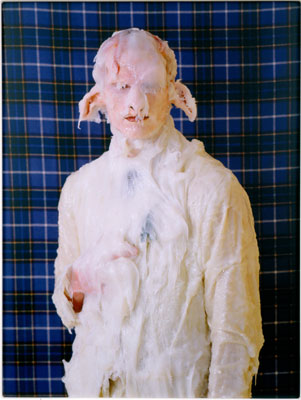

Rush takes a long view in his application of the term "new media." The show is all film, video, and photography, and encompasses about fifty years (Andy Warhol is here in Polaroids and video, getting made up for drag, his eyes constantly darting to a handheld mirror to check the progress of his mascara) and even jumps back to 1925 with the inclusion of Marcel Duchamp's Anemic Cinema, made in collaboration with Man Ray and credited to Duchamp's female alter ego, Rrose Selavy. The implicit opposition to absent "old media" is productive, since in many cases the artists highlight artifice by referring to the conventions of classical painting and sculpture. A self-portrait by Yasumasa Morimura inserts his airbrushed body in a Photoshop reconstruction of Manet's Olympia, and in a shot from The Cremaster Suite, Matthew Barney, dressed as a satyr beneath a thick membrane of whitish goo, adopts the frontal posture of academic portraiture. Katarzyna Kozyra's Summertale (2008), a twenty-minute video of grotesque violence and obscure ritual, often looks like televised versions of plays and operas--which is fitting, since it's partially set in a dressing room and has Offenbach on the soundtrack--but shot from the vantage point of the posse of dwarves who swarm the drag-queen protagonist. All Together Now (2008), by Harry Dodge and Stanya Kahn, provides a refreshing foil to all the cloying refinement, as Kahn wanders numbly through a suburban wasteland in sexless castoff clothes.

Works by Kalup Linzy and Ryan Trecartin forgo allusions to the art of the past, borrowing instead from television and the internet, which the artists approach as sources of mannerisms and turns of phrase that can be donned and discarded like wigs. The phone dialogue in Linzy's Conversations wit de Churen III: Da Young & Da Mess (2005), unfolds over the kind of back-and-forth cuts commonly found in soap operas, which also supply the melodramatic behavior that Linzy stages. In one part of the series, the chatter is tied to the plot of the protagonist's participation in a Whitney Houston impersonation contest, and deliberate mimicry of pop celebrity meets the unconscious parroting of verbal cliches. Trecartin's dialogue in K-Corea INC. K (Section A) (2009) strings together scraps of pop language ("I personally believe," "You know, maybe it would be, like, a good idea if you got back in touch with yourself?") that are as common and anonymous as the jeans and white tops he and his co-stars wear, and artificial as the stark, orange-white tan line he shows around his waist when bending over.

(Photo by Laure Leber)

While Rush spells out a thesis that cross-dressing has been central to experimental art of the last century, he leaves it to the works he selected to make the argument for why that is so. The Duchamp-Warhol line of the avant-garde that interests Rush has been persistently concerned with art's relation to life, and with the rarefied position of the artist in a time when almost anyone can own and make images. Cross-dressing and costuming in the work of Masamura and Manon, Barney and Handelman can thus be seen not only as self-consciously aesthetic gestures, but also metaphors for art-making as such. The works in "Virtuoso Illusion" are less about gender troubles than the ways in which people try to add excitement, beauty, and drama to their lives. Reality television and Simpsons-style metafictional winks aside, mainstream culture aims for seamless illusion, and unlike the average YouTube user, it has the tools available to make it. But the artists of "Virtuoso Illusion" revel in obvious artifice and reveal the edges of it--a trait shared with drag queens. (Ru Paul: "I do not impersonate females! How many women do you know who wear seven-inch heels, four-foot wigs, and skintight dresses?") Linzy and Trecartin's videos highlight the proliferation of sources where personality tics can be stolen and channels where they can be shown off--and that suggests myths of anti-avatars like Oscar Wilde's won't be drained of their potency anytime soon.