Humorous and surprising, smart and provocative, Rethinking Curating: Art after New Media (MIT Press, 2010) jumps from opposing viewpoints to opposing personalities, from one arts trajectory to another. The entire book is a dialectic exercise: none of its problems or theories are solved or concluded, but are rather complicated through revelations around their origins, arguments and appropriations. Overall, the book adopts the collaborative style and hyperlinked approach of the media and practice it purports to rethink. In other words, it is not just the content of the book that asks us to rethink curating, but the reading itself; by the end, we are forced to digest and internalize the consistently problematized behaviors of the “media formerly known as new.”

Sarah Cook and Beryl Graham, co-editors of the CRUMB site and list (the Curatorial Resource for Upstart Media Bliss), have co-authored the book via email and on a Wiki, and assert outright that it is not a “theory book”; its structure instead “reflects the CRUMB approach to research, which discusses and analyzes the process of how things are done” (12). The sheer number of examples, citations, and first-person accounts in this nearly 350-page volume make it so that every time the trajectory coheres into a singular point or argument, it is then broken up again, into a constellation of ideas that make us rethink, again. We are issued challenge after challenge to our assumptions about media, our understandings of curatorial practice, and our opinions about the spaces in which we exhibit art. It is only after an exhaustive study of seemingly irreconcilable philosophies, practices and venues, the book implicitly argues, that we can begin to engage with what needs to be rethought, and how to do so.

Rethinking Curating makes three basic arguments. First, that one must approach a broad set of histories in trying to understand any given artwork, and “for new media art this set includes technological histories, which are essentially interdisciplinary and patchily documented” (283). Second, that such broad histories have led to the unique development of “critical vocabularies for the fluid and overlapping characteristics of new media art” (283). Cook and Graham reason that new media are best understood not as materials but as “behaviors” - participatory, performative or generative, for example. And third, that these behaviors demand a rethinking of curating, new modes of “looking at the production, exhibition, interpretation, and wider dissemination (including collection and conservation) of new media art” (1).

-->The first 5 chapters, Part 1 of the book, examine “those characteristics peculiar to new media art and the histories of art relating to those characteristics” (13). Chapters 1 and 2 begin by attempting to make sense of the histories, theories and behaviors surrounding the ever-changing landscape of new media. Of special note is the authors’ understanding of the “hype cycles” of all art forms - which go through technical discoveries, inflated expectations, disillusionment, enlightenment, and finally acceptance (24) - and their explanation of how new media are most often unfortunately and unfairly lumped together, rather than being separated into, for example, net.art, virtual reality, robotics and interactive video. Each of these, they remind us, is not only at a different point on their hype cycle, but also traveling at a different speed across the slope (39). Only when “the peak of inflated expectations” for each medium has passed can the “long-term effects… upon the world of contemporary art” be “open for consideration” (284).

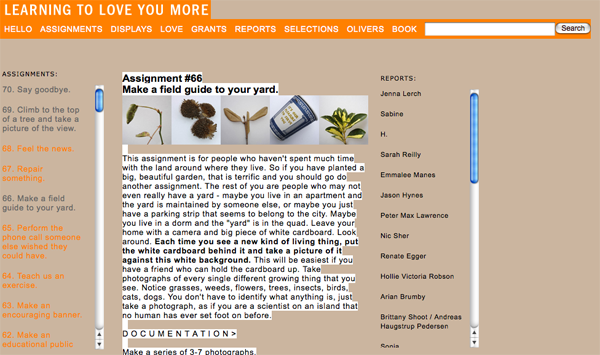

Chapters 3, 4 and 5 then look at space and materiality, time, and participative systems, respectively, as they relate to arts production and curatorial practice. Here Cook and Graham put forward various taxonomies for explaining, for example, “interaction” as opposed to “participation” and “collaboration.” These are defined not as definitive, but in order to differentiate behaviors and modes, and use them strategically in art-making and curation - and thus in how art is experienced and/or acted upon (112-114). Some of the gems in these chapters include statements like “time and space are particularly difficult to separate in new media” (87), or the case studies, which include the Walker Art Center (73), Harrell Fletcher and Miranda July’s net.art classic, Learning to Love You More (103), and the Medialounge at the Media Centre, which broke up the audience experience into passive, active and sit-down/reflective “zones” (103). The book astutely reminds us that while not “all new media art involves interaction or participation,” curators must always question the “relationships among artist, audience, and curator” (111).

Part 2 of the book, chapters 6 through 10, expands upon models of curating, both inside and outside of institutional systems. How can curators, the authors ask in chapter 6, “account for the behaviors of works of new media art, and what logical curatorial procedures” might they undertake in response? (147) They ask this with an understanding that the interface of new media is not just a practical one, but can actually change the meaning of the work itself (284). Here, Cook and Graham argue, the best practice for new media is “not to recapitulate old ways of working,” such as more traditional exhibitions, but to find new modes of “production and distribution that best fit the art” (147). Its curators need to “engage in translation between the systems of contemporary art and new media art” (16), must work across “exhibiting and interpretative events… online and real space… content and contexts” (168). They are producers, collaborators, champions, outsiders, quoters, surgeons, communicators, and more (156).

Chapter 7 goes to great lengths to understand the interpretation, display and audience of new media art more generally, whereas chapter 8 understands new media in the art museum, and chapter 9 looks at “non-collecting exhibition spaces” (215), such as science museums, trade shows and conferences. The authors remember, on the one hand, that museums are where art history is made (189), and that each “exhibition is itself like a temporary collection” in how it fits into the museum program and identity (150). On the other hand, they continuously remind us that “an artist doesn’t need the official sanction of the art system in order to be included and noticed by the art world” (221), and that “new media art can potentially change” institutional systems of exhibition and conservation “into something more fluid, albeit perhaps more messy in terms of archive” (211). Finally, they discuss “hybrid modes of working outside the museum but within the landscapes of contemporary art and digital culture, from the biennial to the blog to the lab” (247). They do this in looking at the work of artists like Vuk Ćosić, and spaces such as V2 in Rotterdam.

The most salient points of the entire book - and those that will make Rhizomers and new media art junkies more generally smile and cheer - take place in chapters 10 and 11. The former talks about the benefits and shortcomings of showing in different kinds of spaces, from artist-led ways of working to audience-led (248). In chapter 10, the authors astutely assert that, “it is impossible to argue that new media art, like any other form of emerging practice, has ever been anything but artist led” (251-252). They give as two examples here the infamous Whitneybiennial.com (Miltos Manetas, Patrick Lichty and Michael Rees), a kind of hoax intervention in New York that never occurred (254), and NODE.London, a UK-based media art network. Chapter 10 also reminds us of the curator’s vital role - even in artist-led networks - as registrar, administrator or programmer (271), but also of how fun this might be. Citing themselves/ their own CRUMB biography on page 283, they aver, “Once you’ve curated new media art you’re unlikely to curate anything else the same way again.”

And chapter 11 - the book’s conclusion, billed as part 3 - finally asserts that “New media art presents the opportunity for a complete rethink of curatorial practice, from how art is legitimated and how museum departments are founded to how curators engage with the production of artwork and how they set about the many tasks within the process of showing that art to an audience” (283). This work is not about “art in technological times,” but “life in technological times” (286-287), and thus the best way to curate it - “to produce, present, disseminate, distribute, know, explain, historicize” it - is to know “its characteristics and its behaviors, rather than imposing a theory on the art” (304-305).

Rethinking Curating is an encyclopedic study of new media practice - about making, showing, viewing, curating, thinking and writing. I recommend it in three modes: as inspiration, with the sporadic skim of random chapters - I kept taking notes, excitedly reflecting on how I might apply many of the ideas presented; as a classroom text - various parts of the book might work in courses on, for example, art, education, conservation, and of course curatorial practice; or as research - the thinking, case studies and references are extensive. Without a doubt, this book is a necessary part of any new media art library, and will be an important document in years to come.

Nathaniel Stern (USA / South Africa) is an experimental installation and video artist, net.artist, printmaker and writer. He holds a design degree from Cornell University, studio-based Masters in art from the Interactive Telecommunications Program (NYU), and research PhD from Trinity College Dublin. He is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Art and Design at the University of Wisconsin - Milwaukee.

Your words drew me in to all that is so "un-trendy" and exponentially fascinating about this topic AND in broad, cohesive strokes.

I feel that there is a new calling for artists/writers in today's digital world (where shock and incomprehensibility is only a click away) to bring meaning and yes, I'll stretch a bit, comfort, to those who have no navigation, story line or compass by which to make sense of this glorious information mess . . .

Beauty, (even when ugly, which it often is when raw), has always had a deep sense to it. Ok call it truth.

I say "more glue, more discovery, more touch." (digit)

Your review and this book looks to be a step in that direction, grasping at the larger seminal meaning of this ongoing digital revolution which is changing art, life.

Roz

thanks, roz! it's a worthy read. best,

n

Thanks Nathaniel for the great review. Just one point of correction: in the last section I think you've inadvertently mixed up two different examples. NODE.London is a collaborative artist-led initiative which produced a few 'seasons' of media art. It is not by Nina Pope and Karen Guthrie, though we write about their project TV Swansong and other of their online / network-based / artist-led projects elsewhere in the book. We'd love to hear from others about what they think of the book too, no doubt we've missed a lot out!

Cheers

Sarah

thanks sarah - i'll see if we can't correct that; must've gotten mixed up in all my notes. best,

n

Hi Sarah,

Removed Nina Pope and Karen Guthrie's names from the sentence on NODE.London - thanks for pointing that out to us!

Best,

Ceci

I'm reading the book, and I agree with Nathaniel - it's definitely a worthy read. I've just finished reading chapter 3, so it's really too early for any thoughtful comment. By now, I agree with Sarah and Beryl that new media are increasingly changing curatorial practice, but I still have to be persuaded that new media art requires a different model of curating. I think that the overlapping between new media and new media art - between the art and the medium - is one of the most dangerous mistakes of new media art criticism, and I hope this book will bring the discussion to a step further.

Also, I'm still not sure of the opportunity to talk about new media art as something "different". In chapters 3 - 4 - 5, there is a comparison between dematerialized / time based / participatory works from the contemporary art history and new media art. The comparison is introduced by the title line "How New Media Art Is Different". My question is: is new media art really different? Wouldn't be better to say that new media - whether they are used as a medium or not - are forcing us to rethink the concepts of materialization, time and participation? Can we still think about material and participation in the same way as we did in the 70s after the digital revolution?

The distinction is subtle, but I think crucial - both conceptually and strategically. Saying that "New media art presents the opportunity for a complete rethink of curatorial practice" we are still putting new media art on a throne, in a way that the contemporary art world will never accept.

So, as I said - I have great expectations! Thank you for giving me something able to keep my two neurons alive along this hot summer :-)

domenico

The review in its sympathy for history according to multi textual resourcefullness finds , implicitly restates, the traditional openendedness that is this approaches decisive signature. But it has been upon me for some time to wonder…whether the successfull deconstructing away of the idea of "essential" constructions as being only quasi informed does not in turn perhaps yield a question as to the origins of intuition. I am not convinced by the wake and trough of activity that surround the opening of this book according to the reviewers take intuition and by this I mean the older perceptions of wholenesss accruing within perception of perception have not become confused and tangled threads of critical editing of approach modes

I just bought Beryl & Sarah’s other two books that just came out—“A Brief History of Curating New Media Art: Conversations with Curators” and “A Brief History of Working With New Media Art: Conversations with Artists”—so I’m curious what insights this third book will offer that weren’t in the other two? I’m guessing from the review that this is more about their take on things than what was presented in the two interview collections. Just wondering if this fills a gap in the other two, and if so, what that gap may be?

In reply to the previous post from Chuck Ivy

Just to let you and other readers know – the two volumes published by CRUMB together with The Green Box in Berlin (a brief history of curating/working with new media art) are newly edited reprints of material from the CRUMB website which we have been working on for a decade (see www.crumbweb.org). These interviews/conversations/dialogues are from events we have hosted and firsthand research we have done talking to curators over 10 years. The longer versions of most of the texts in those books are available online, but we thought it would be great to work with Axel Lapp (CRUMB's one-year senior research fellow) to revisit that material and make it available in book form, as a kind of 10 year birthday present to ourselves and to you! We released them to coincide with the Rethinking Curating book which Beryl and I worked on over the last five years with MIT Press, which is a larger co-authored volume, more historically minded, more academic, and drawing on these events but also material from the CRUMB discussion list, and our firsthand experience of curating and researching the literature in the field.

I wouldn't say that one book fills a gap left by the other. The interview/conversation books are 'straight from the horses mouth' (whether artist or curator or producer) and deal with topics ranging from collection to exhibition, press and reception, technology, and museum or gallery working. They are a kind of picture of a moment in time. The Rethinking Curating book provides, in our mind, a longer more detailed examination of the field with examples from artists works and from the history of curating, sometimes citing these interviews/dialogues, sometimes not. There is newer stuff in The Green Box books, in that they include conversations from 2009, after the Rethinking Curating book went to print - such is the nature of the publishing industry. In our minds, they make lovely companion volumes, and excerpts from both could be useful in a teaching context.

Looking forward to hearing more feedback from Rhizome readers.

Cheers

Sarah

I'm really interested in the role of a printed book is in this context.

There is an element of celebration (and ownership?) inherent in the medium.

Also of income (if we're lucky!) of course.

I have feet in both media (sounds messy), having a digital role for a print publisher.

John

The book sounds like a very interesting book, for artists and curators, and I am both.

I will eager to read it when I get back to the States.

Although again with Rhizome, it always sounds as it is "preaching to the choir" for

a short, select list. The open free quality of Rhizome is gone. I would be interested to

see more non institutional connections outside of the usual.

and instead we live in the ideal and fantasy of what Summer becomes. We anticipate this time of year with a child like earnestness and we willfully throw ourselves into a haze, from which we slowly find our way back into reality.

YAK ReMiX YAK ReMiX YAK ReMiX Music Art Music Art Music Art Yes, I know….I have issues. Probably that lead paint I gnawed on in the apartment in the bronx where I was a baby? JOHN F. McArdle Born 1956 BRONX NEW YORK Parents(Irish catholic immigrants)Father- James F.McArdle( decorated korean war combat veteran) presently still alive as of today August 10th 2010 and poster child for PTSD syndrome. He was made an american citizen in the field of battle in Korea. Mother Philomena M. McArdle/Sharkey also presently alive. Childhood friend in Ireland the Famous Tommy Makem, Of TOMMY MAKEM and The Clancey Brothers. Need I say more? We will not be disscussing My military career or the abuse I recieved from my father. I am presently the drummer for YAK ReMiX and partners in The WIZ sound Company. We desperately need some corporate sponsorship as our financial resources have become very meager. I feel humbled and neglected presently. A desperate message to the universe and the powers that be.Please! GIVE ME MY DREAM! THIS has absolutely nothing to do with "New Media, New Modes: On "Rethinking Curating: Art after New Media"………….THE END.