Addressing the American Association of Museums in 1941, Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, then curator at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, put forth a fundamental question: "What is an Art Museum for?" He proposes that the answer is contained in the term "curator," which implies that "the first and most essential function of such a Museum is to take care of ancient or unique works of art which are no longer in their original places or no longer used as originally intended, and are therefore in danger of destruction by neglect or otherwise." Significantly, Coomaraswamy's concept downplays one curatorial activity otherwise taken for granted today: "This care of works of art," he writes, "does not necessarily involve their exhibition" but if an institution does choose to exhibit works, "this is to be done with an educational purpose." Moreover, he adds, "it is unnecessary for Museums to exhibit the works of living artists, which are not in immanent danger of destruction."

Coomaraswamy's antediluvian pronouncements, predating both the development of the modern computer and the institutional embrace of contemporary art, nonetheless provide a way to think about the assumptions underlying the twelve essays in Christiane Paul's collection New Media in the White Cube and Beyond: Curatorial Models for Digital Art, recently published by UC Press. For even if Coomaraswamy's skepticism about the value of exhibiting living artists now strikes us as thoroughly outdated, his general concerns continue to inform the questions posed by Paul and her contributors. For new media, the problem of how to deal with artworks "no longer in their original places or no longer used as originally intended" remains salient -- albeit for technological rather than antiquarian reasons -- and all of Paul's essayists propose some version of what necessary "educational purpose" curators of new media must embrace.

As a mix of critical musings on the nature of curating and case studies of particular exhibitions, Paul's book is not alone in its scope. Several of the contributors to New Media in the White Cube and Beyond also appear in Curating Immaterality: the Work of the Curator in the Age of Network Systems (2006), and two of Paul's writers, Sarah Cook and Beryl Graham, have their own collection forthcoming from MIT Press, tentatively titled Curating New Media Art. In turn, these books exist in a larger context of recent anthologies on the philosophy and history of curating and exhibition of contemporary art: Julie Ault's Alternative Art New York, 1965-1985 (2002), Paula Marincola's What Makes a Great Exhibition? (2006), Paul O'Neill's Curating Subjects (2007), Mike Sperlinger and Ian White's Kinomuseum: Towards an Artists' Cinema (2008), and Hans Ulrich Obrist's A Brief History of Curating (2008), to name only a handful of examples. The role of the curator has never before been so heavily theorized.

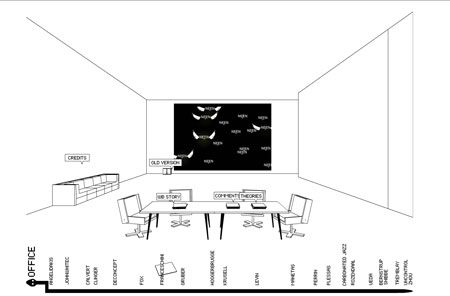

The central thesis of New Media in the White Cube and Beyond, outlined in Paul's introduction and affirmed in various ways throughout the book, is that new media art "challenges the traditional art world -- its customary methods of presentation and documentation, as well as its approach to collection and preservation." Paul's own contribution, "Challenges for a Ubiquitous Museum: From the White Cube to the Black Box and Beyond," discusses various difficulties with a pragmatic, nuts-and-bolts outlook. For example, she notes that standard "loan agreements" poorly meet the needs of exhibiting web-based work in a museum. The technical limitations of most institutions, which largely hew to the white cube / black box model, often precipitate the need for separate, dedicated spaces specifically for new media art. "The 'ghetto' of the new media area is commonly considered the epitome of the uneasy relationship of institutions with new media at this time," Paul writes, but "if museums have designated (sometimes sponsored) spaces for new media art, they are also obliged to offer programming for these galleries, guaranteeing the art form a regular exposure."

Paul, adjunct curator of new media arts at the Whitney and organizer of numerous exhibits worldwide, believes that museums must meet the needs of new media artists, not the other way around. She addresses several common complaints on the part of audiences to new media art (such as "It doesn't work" and "It belongs in a science museum") and proposes that the role of institutions is to "be aware of new media's precarious position and open up spaces where this position can be discussed" without becoming "overly didactic, making art only a vehicle for educating the public." Paul argues that new media and more traditional "art objects" can equally participate in the museum, and that new media has the potential to broaden the appreciation and understanding of art history as a whole.

Offering one specific change museums could undertake, John Ippolito's wry "Death by Wall Label" argues that the very "cultural survival" of new media rests in how artworks are described in exhibition captions. He proposes a new model for textual description that takes into account the variable nature of materials, authorship, and performance, suggesting that each public exhibit be numbered along the line of software versioning: Nam June Paik's "TV Garden v.1.12 (New York, 2000)", for example. Caitlin Jones and Carol Stringari's case study of their 2004 exhibit Seeing Double: Emulation in Theory and Practice at the Guggenheim tackles the same issue in a related manner. The show contained original media-based artworks alongside new emulations of the same works, pointing towards future strategies for exhibiting art based on ephemeral or obsolescent technology, and thereby allowing visitors to assess for themselves what if anything had been lost in the translation.

While these writers claim that museums need new media artists, they also note that the feeling isn't always mutual: at numerous times, the authors stress that new media art -- especially net art -- by its nature is not dependent on institutions for exhibition and community-building. "To a nonspecialist public, museums and other mainstream institutions are often the most visible part of the art world food chain," Steve Deitz writes, "but this does not mean that they are the most critical for contemporary art in general or net art in particular." According to Patrick Lichty, this means that a new kind of curator is necessary for new media, one "whose venue is not the institution, and whose audience is not the museum-going public." Nonetheless, purely online curatorial projects have their own pitfalls: Dietz questions "whether we can and should create interfaces that function like butterfly vivariums or eco-tourism -- guided tours of net art in its native habitat."

Sarah Cook proposes a more radical rethinking of the curator's role. "Formalist aesthetics and its attendant value judgments must be reevaluated if we are to understand the often relational aesthetics of new media," she writes, observing that curators now "increasingly act as filters and commissioners, seeking out opportunities for meaningful exchange between the artist and community parties," then offering six conceptual models for curating both within and beyond institutions. Cook's invocation of Nicholas Bourriard's relational model dovetails with observations made elsewhere in the book that the roles of artist and curator have blurred beyond the mere necessity of collaboration. Lichty cites the emergence of work in "cultural autonomous zones" like Miltos Manetas's whitneybiennial.com (2002), an unofficial, online group-exhibition-cum-provocation that ran concurrent with its titular object of critique, and Miranda July and Harrell Fletcher's Learning to Love You More (2002) which could be seen simultaneously as "a social sculpture, a collaboration, or a cultural appropriation under a specific social contract."

No doubt thanks to the snail's pace of academic publishing, New Media in the White Cube and Beyond doesn't address the most recent developments in the field: most of the essays appear to have been written several years ago, with only minor updates on the eve of publication. Thus the fundamental shifts of web 2.0 are nearly absent: neither "blogs," "social networks" nor "YouTube" appear in the index, though the first phenomenon is given passing mention in Lichty's contributions. How the acceleration of social interaction online has affected the growth of "cultural autonomous zones" would be a topic for further investigation, as would be looking at newer phenomena such as surf clubs or art-blogs like We Make Money Not Art and VVORK as quasi-curatorial forms.

More striking is the fact that a major aspect of curating never arises: that of taste, one of the most crucial faculties required in a curator. With all the analysis of curator as filter, educator, or collaborator, the job is posed largely as that of a social facilitator whose creative input takes place on the level of new curatorial models -- still essentially charged with "taking care" of art as in Coomaraswamy's day. While this is undoubtedly a key responsibility for curators, one should not downplay the factor of aesthetic judgment necessary for every successful curatorial project. The question of which works of art are chosen for exhibition is at least as important as how we end up experiencing them. The larger topic of how and why curators construct systems for determining the value of new media art thus remains open to further conversation, beyond the important ideas Paul's collection already explores.

Ed Halter is a critic and curator living in New York City. His writing has appeared in Artforum, Arthur, The Believer, Cinema Scope, Kunstforum, Millennium Film Journal, Moving Image Source, Rhizome, the Village Voice and elsewhere. From 1995 to 2005, he programmed and oversaw the New York Underground Film Festival, and has organized screenings and exhibitions for the Brooklyn Academy of Music, Cinematexas, Eyebeam, the Flaherty Film Seminar, the Museum of Modern Art, and San Francisco Cinematheque. He currently teaches in the Film and Electronic Arts department at Bard College, and has lectured at Harvard, NYU, Yale, and other schools as well as at Art in General, Aurora Picture Show, the Foundation for Art and Creative Technology, the Images Festival, the Impakt Festival, and Pacific Film Archive. His book From Sun Tzu to Xbox: War and Video Games was published by Thunder's Mouth Press in 2006. With Andrea Grover, he is currently editing the collection A Microcinema Primer: A Brief History of Small Cinemas. He is a founder and director of Light Industry, a venue for film and electronic art in Brooklyn, New York.