Frank Eickhoff, Application To The Entscheidungsproblem, 2010

A headless statue of winged Nike, black pixels swarming above her stumped neck. A collage of ancient, sand-colored busts and patterns drawn with a Sharpie. A Michelangelo’s Pieta coated in blue-streaked purple sludge. These are some of images you will find on Sterling Crispin’s Tumblr, “Greek New Media Shit.” As I write this, the most recent post is a looped animation by Jennifer Chan. Two Hellenistic statues remain static in the foreground as a violet blob belches out a browser frame. Flat green letters brand it “recipe art.” Chan, apparently, thinks mixing classical references with internet imagery is formulaic. The opinion is somewhat sympathetic to Crispin, who told me in an email that his blog “started as a criticism of a cliché that I identified and has started self-perpetuating.” But Crispin added that since he started the Tumblr he has become more curious about the reasons behind the formula’s appeal. No recipe passes through so many hands without being good.

To me it tastes like a desire to locate man’s place in a world that he perceives primarily with the aid of machines. The art of the Greeks has been used in the past as a touchstone for artists who measure their own vision against an anthropocentric one. “Greek art had a purely human conception of beauty,” Apollinaire wrote in an essay about a 1912 exhibition of Cubist painting. “It took man as the measure of perfection. The art of the new painters takes the infinite universe as its ideal, and it is to the fourth dimension alone that we owe this new measure of perfection […].” The modernists never determined what the “fourth dimension” was, besides a plane of activity beyond human perception. Today the internet—and the spatial and perceptual relations it has engendered—make a familiar substitute for it. “Greek new media shit” puts representations of the visible and the invisible in the same frame.

Sara Ludy, Red Easter, 2010

Several posts to Crispin’s Tumblr depict classical statuary bathed in slime from the least natural regions of the Photoshop palette. But that’s not the only way artists have engaged the theme. Angelo Plessas is a twenty-first century Greek who works with the physics of Flash, exploring how architectural issues of materials’ interaction in space unfold when material and space are made of code. On his site Not Only Possible but Also Necessary, Medusa masks spin at an arch’s twin bases. Snakes slither through their hair and expel water. When the site is fully “submerged,” it starts over from the beginning. The central image is a building loosely constructed from negative space: the columns are black silhouettes, the windows and doors are made “distant” by their relatively small size. The architectural elements suggest the outlines of a face: windows for eyes, a door for the mouth. It’s an iteration of Plessas’ favorite emoticon leitmotif, which might be read as playfully inverting the golden mean, the Greek aesthetic theory that transformed the proportions of the human body into criteria for architectural form. Not Only Possible but Also Necessary flattens time as well as space: the timelessness of ruins is recoded as an animated loop.

Grinding on the Greeks, a site by Nicolás Colón and Nick DeMarco,* puts da club in the museum in a gesture of late late Dadaist collage. Viewed one way, the antique sculpture in the background fills the same function as Richard Serra does in DeMarco’s family portrait of him with Michael Cera. But Grinding on the Greeks is not just a negation of a cultural hierarchy of our time—it’s an encounter between widely held standards of beauty from two times. The dancer is mostly naked, a personification of America’s erotically charged youth culture with a thong riding up her hip. Yet her gyrating pelvis prudishly blocks the ephebe’s marble junk. Both the girl and the statue are anonymous manifestations of cultural trends that extend far beyond them. Like Plessas in the work described above, DeMarco makes use of the whole window: the URL and the page’s title make a double caption. The browser is a discrete zone where values can be digested and transformed, and where the result can be displayed.

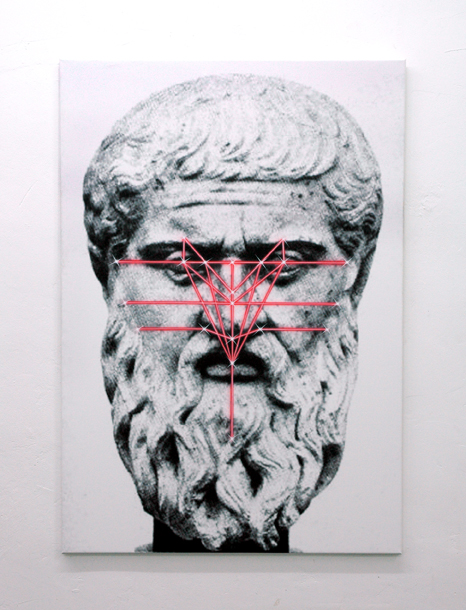

Aids-3d, Plato with Biometric Overlay, 2009

The web site of Aids-3d used to feature a proto-Tumblr that freely mixed images of classical art and architecture with computer-rendered bodies, robots, and virtual reality goggles—an archive where humanism jostled with the post-human. “Speculations on Cosmic Culture,” the collective’s 2009 exhibition in Berlin, wondered if humanity’s dependence on technology has endangered it as a species. The show’s signature image was Berserker, a man-sized Styrofoam alien. Its pose mimicked contrapposto, a breakthrough of classical sculpture that introduced an asymmetrical stance to suggest a mind at work inside the stone head. Contemporary touches—the peace sign given by the alien’s raised left hand and the Flash drive in its right—mockingly exaggerate the human qualities attributed by the Greek allusion. “Automated Mission Report: 3rd Planet of the System Sol,” reads the statement for Heat Death, a video work that was displayed on a computer near the statue. “No sign of sentient life... Humanity is wiped out in the near future and this crappy screensaver is the closest we get to creating the Omega Point simulator/ computer.” The alien has arrived to claim the dominion of man, who vanished in his own files.

Oliver Laric’s Versions (2009, 2010) are essays on the dissemination of visual culture that draw examples from pre-modern times as much as internet culture. In his ahistorical take on reproduction media, the press molds that let Greeks take small souvenir sculptures from temples are more or less the equals of contemporary image incubators like 4Chan and Tumblr. His Kopienkritik, recently installed at Skulpturhalle Basel (covered previously on Rhizome) interpreted those ideas in space by assembling collecting statue copies and using them as screens for Versions. In the ancient world, few traveled enough to see replicas of the same statue at far-flung temples, but now—when travel is accessible and common—a temple of contemporary art like Skulpturhalle Basel has the resources to put near-identical pieces in one place for the viewer’s cool perusal. Laric largely ignores the value systems propagated by antique art, focusing instead on the systems of production of distribution. As Tom Moody commented, he is “literally projecting present day attitudes and values onto the past.” The humanist worldview recedes to the background, supplanted by a fascination with media.

Oliver Laric, Hologram / Chippendale, 2011

Versions is, in part, about the increasing irrelevance of the Romantic ideal of the artist as the possessor of a unique, original vision amid a hyper-productive visual environment. In this respect, Laric’s references to medieval and ancient art are appropriately evocative of non-Romantic modes of conceiving culture. But the value shift slips out the bottom. By foregrounding systems, Laric’s critical inquiry espouses an attitude that is realized, tongue in cheek, by Aids-3d in “Speculations on Cosmic Culture”: man vanishes, his artifices remain. Both works respond to the ease of creation in the digital age, where the means of production and distribution become more important the image itself.

If the ancient artist worked in service of truth and beauty, the contemporary artist serves to propagate the system he is participating in. “Recipe art” loses its sting as an accusation when the formula is not just a way to make an image but a representation of man’s technologically mediated encounter with his environment. Sterling Crispin’s archive, originally intended as a critique of a cliché, ironically took on a life of its own as an artist’s statement without an artist—an autobiography of a meme acquiring significance in its iterations.

Thanks to Sterling Crispin and Allyson Vieira for their discussion and insights.

*update: A "site by Nick DeMarco with programming by Nicolas Colon" corrected to read "site by Nicolás Colón and Nick DeMarco."

As a point of interest, I think the Basilica Cistern in Istanbul was the inspiration for Angelo's piece:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basilica_Cistern#Medusa_column_bases

Honestly, though, a big reason a lot of these statues and buildings are used in 3D is because they are some of the most freely available stock 3D models…

Good to know. But why do people who make stock 3D models make them? I have no idea, but I'd guess that it's because these statues and buildings are considered paragons of sculpture and architecture and designers want to prove that 3D modeling software is capable of imitating that. So it fits with what I'm arguing here.

Some of the reasons have to do with the technological and interface conventions of 3d modeling software - for example, a basic Greek-style column can be generated in a couple of minutes by beveling the faces on a cylinder primitive. These structures make excellent educational tools for 3d modelers, as they do for art history students.

In the case of sculpture, one could perhaps point to the attractiveness of these objects as targets for 3d scanners and the desire to digitally preserve something that's inherently subject to decay.

Another factor to consider is the replicated status these objects achieve within virtual worlds - they're used repeatedly to line hallways and beautify rooms, and in doing so they lose their status as artistic objects and become mere deindividuated decorative placeholders. This seems to me the critique that much of the artwork mentioned is levelling, and ironically one to which it is also subject.

It's interesting that so few artists have used the kind of default 3D models that are widely used in the industry and available in all 3D modeling software (Utah Teapot, Stanford Dragon, Stanford Bunny, Suzanne). Ceci did a series of posts several months ago and we could only find like two or three.

So while this may be a question of defaults it doesn't seem to be reflecting on technologically specific defaults, just culturally specific defaults and readily available forms.

Actually a lot of artists are exploring the defaults of this world but still making aesthetic choices. If it's between the teapot/bunny or the 3d babes/artifacts, the latter have an easily built-in art historical context and are a little more sensually and formally enticing. I do think it's an irresistible trope to mix ancient with new, one that will continue to repeat itself even if it also begins to mimick itself at the same time. Most of the work I see like this just seems like someone is playing in 3D for the very first time, which is a bizarre experience and one that seems to create the same reactions year after year.

Essentially, though, there is an entire lexicon of the "free" 3D world, one of babes, columns, pottery, office supplies, tons of handheld consumer products and banal landscape enhancements. Isn't this what a lot of internet and software engaged artists are doing? Just using the uncanny lexicons that are created by things like search queries, software defaults, advertising language, etc., supposing it as a real world and creating an intimate or more critical concentration of that language to re-mystify it or make fun of it?

I think the early days of 3D found the technology primarily used for architecture and artifact preservation/replication so of course buildings and famous ancient sculptures were some of the first things to be scanned or modeled by facilities that could afford to do it.

So whats this essay prove? That greek references within art online are overused and obvious?

I think he meant that Greek references were indeed prolific, and also:

1.) "a representation of man’s technologically mediated encounter with his environment"

2.) "a meme acquiring significance in its iterations."

In terms of web art trends could we also talk about the treatment of the yin yang sign on tumblr/Facebook as art? I'm not sure if people find it profoundly cute and different, or if it's exotoc and trendy.

As someone who's grown up in Asia I feel like this sign is so religious/historical and anachronistic that it can't be reclaimed or used arbitrarily. (Imagine trying to use any other religious symbol to make a statement on capitalism.) I also feel like having multiple irl copies of them as sculptural art objects probably wouldn't reinforce their significance or talk about our encounter with technology…

[img]http://filtermagazine.com/images/uploads/dks.jpg[/img]

is that humanist?

I'd say secular humanist.

I don't think a yin yang is humanist! Also I think that its use in net art is about New Age and hippie culture, i.e. a Western phenomenon that borrowed from (and distorted) Asian culture, and not about Asian culture. I think this could be a topic for another discussion thread.

I think it's both hippie and hipster-an exotic apolitical fetish. I just think in an Asian new media exhibition context this would look so fug, though it functions fine on the internet.

before people started responding with all the images I was going to compare its use to trying to reclaim the swastika, though the yin yang is also not as ideologically problematic.

As an art text the symbol also doesn't have as heavy a canonical resonance like the greek stuff in academic art. I just feel it's more kitschy than reappropriated greekness, that is all. I am not saying you can't use it.

[img]http://www.immateriallabour.com/obvstrollisobvs.jpg[/img]

imagine

http://qiproject.net/

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dfnOFvZvEuA[/youtube]

this cause is lost,

Claudia Hart's work - like her massive four channel installation of an aging computer generated greek temple come to mind. Its interesting to think of the dichotomy between greek sculpture which is a cultural staple of timelessness, lasting for a thousand years, and technological advancement which during its relatively short history has “eaten its young” constantly renders files obsolete, broken, corrupted, at a pretty tight clip. I think that part, perhaps only a small part, of the fascination with greek art, beyond the irony, is that there is a longing for the direction and cohesion that artists once had before modernism and the death of god (in art). Maybe its like a sigil, a charm, ( parasitic even) place the image of something that has survived for a thousand years inside of you idea and maybe your little box will be spared.

I don't know about you, but I definitely don't sense anything even remotely resembling "irony," or "a longing for…direction" in the bulk of tech-centric works that appropriate Greek shit. What I do sense is a knee-jerk tendency to imbibe a newer and less recognized form of media with the import and officialdom of an aesthetic that has lasted centuries (the architecural style of all major governmental buildings in the US is Greco-Roman, and the basis of all Western democracy is in Greece).

General consensus among most people is that the digital portion of things is what will outlive everything else. Greek art is timeless, yeah, but inversely equating that lasting quality with files on a computer is a little silly; to date, the only multimedia file format I can think of that has operated consistently since it was first started, is a Flash file (aside: Rafael Rozendaal mentioned in a speech that he chooses Flash over a combination of javascript/html/whatever, because Adobe products are backwards compatible).

I agree "that there is a longing for the direction and cohesion that artists once had before modernism and the death of god (in art)." I think this also seques with the spiritual in art, a place where the quest is not so much about what separates us (hey see how unique I am - I mean isn't that obvious? It's almost getting boring to contemplate.) as those deeper things that unite us. (which span the gamut from altruism to violence, darkness to light, an endless bag of tricks unresolvable, that speak to the human heart as well as the mind . . .)

I may be getting off the point here but Sterling Crispin's work certainly speaks to this . . .

Ah yes – what is the "recipe," beyond the ingredients, the unique one to our age that also ties us to ancient practice?

The western world is classically trained. Even when it pretends to subvert this classicism, it is showing its training. It's the same in the East actually. It's really just some kind of false memory of a persons European origins, all this greek shit. As if it's the place where you once belonged. Deep false identification that feels wrong enough to be right, and an attempt to see in plain terms where we have come to in context to where we "were". Who doesn't want to jam with the greats, even if they are just props. Who doesn't wanna feel ancient in a world of displacement. Looking back so hard is actually a way of looking out into the world of infinite now - but with some kind of reference point so you don't go dizzy and fall off the edge. It should be called Greeked, Etc. Just kiddin.

[img]http://matthew-williamson.com/enmst.png[/img]

[img]http://matthew-williamson.com/gnms1.png[/img]

replace img of cat-like thing and/or castle with 3d render of r2d2

[img]http://matthew-williamson.com/pinms.png[/img][img]http://matthew-williamson.com/cnms1.png[/img][img]http://matthew-williamson.com/dnms.png[/img]

PS Brian I'm sad there was no "GREEK TO GEEK" flowchart timeline graphic. Also, the next thing I want to see called out is SEINFELD NEW MEDIA SHIT?

If you make it, they will blog.

[img]http://matthew-williamson.com/snms.png[/img]