The latest edition of Abandon Normal Devices (AND) Festival has jumped across the Northwest UK from Liverpool, where it debuted last year to Manchester. In its second major urban manifestation, after a small rural retreat in the Peak District, the festival followed its previous format and presented exhibitions, performances, cinema screening, talks and workshops across cultural venues in the city. Seeking to agitate, AND’s theme of questioning normality in various forms was represented in Manchester with a focus on identity.

The festival showcased two artists presenting debut feature films, Gillian Wearing showing Self Made and Pipilotti Rist showing Pepperminta. Both artists elaborately explored the personalities and subconscious of the characters portrayed on screen in entirely different ways.

Wearing began the search for the film’s characters by advertising in newspapers and job centers:

“Would you like to be in a film? You can play yourself or a fictional character. Call Gillian”

Merging and interchanging the real and imagined lives of seven selected members of the public, Self Made documents the participants’ exploration of personal and social identities, deconstructed and constructed through a hybrid of performance and method acting processes.

Sensitively negotiated workshop session scenes, led by acting coach Sam Rumbelow, punctuated the fictional, theatrical or cinematic scenes devised by the chosen ‘actors’. Each participant went on a journey through three stages-method workshop, the final cut of their film scene and the behind-the-scenes action of the filming process.

Part documentary, artwork, and anthropological experiment, the film’s discourse of personal discovery through performance makes for (at times) uncomfortable viewing. Drawing on the darker side of human nature, the participants were encouraged to develop scenes that evoked a strong personal affect, resulting in a sometimes brutal physicality on screen, where acted out scenes heightened and reflected the relationship between human experience and the construction of filmic narrative.

The content of the film was molded and driven by the participants along with the method acting coach. Yet, Wearing and the screenwriter’s presence are conspicuously absent. The fragmented presentation of the participant’s scenes raises the question of whether it succeeds as a feature film in a cinema environment. Perhaps it would play out more effectively on television, the neat sections of the film would produce nice pauses for advertising breaks, thereby adding to the sense of disillusionment with reality.

Pipilotti Rist’s move to the big screen is, in contrast, made of strawberry filled animations, spinning camera shots, fuzzy close ups and jerky angles from the snail’s eye view. We follow the freewheeling central character, Pepperminta, on an adventure that’s an orgasm of color and menstrual blood.

The film jumps between her childhood and her mission to spread color and ecstasy to the people. Following the guidance of her music box, which houses the disembodied wise eyeball of her grandmother, she first recruits a simple minded accomplice in an Amélie-esque postal game and cures him of his perpetual allergies by smothering his face in tulips. She trains her companion in the art of hypnosis through exposure to a color-wheel and, afterwards, they run around spreading joy on buses and pavements. The strong visual glue of bodily fluids and color tied together Rist’s particular brand of lowtech psychedelia, resulting in an ultimately enjoyable, although overly sentimental adventure.

As is frequently the case while trawling a festival spread across numerous city sites, it is often the fleeting and unexpected encounters with works that prove to be the most enjoyable, this was the case with Nelly Ben Hayoun’s Soyuz Chair Performance.

The work was tucked away in the corner of a show titled “Designed Disorder” at CUBE (Centre for the Urban Built Environment), which featured a number of graduates from the ever-interesting Design Interactions MA at the Royal College of Art.

Trickery, imagination and conspiracy have always played a fascinating and central role in the fantasy of space travel. Welcoming mass suspension of disbelief, the artist solicits an imagined trajectory for the rocket launch; she invites the participant to undertake a journey in a NASA-upholstered domestic armchair. The Soyuz Chair Performance reproduces the three stages of a 1966 Soyuz rocket launch. Despite aesthetic derision, the space apparatus and the paraphernalia that make up the simulation and thrust of take off is remarkably effective in creating the sensations of propulsion. Nelly Ben Hayoun heightens the sensation with a combination of accurately recreated vibration and deafening sound.

My cosmonaught friend Nicola Singh was assaulted on the launch pad and thrust towards the stars as a large crowd gathered to watch, drawn in by the thunderous raw of the booster rockets. The experience itself was described as disorientating and otherworldly.

The moving image highlight of the festival was Phil Collins’ beautifully constructed, marxism today (prologue) (2010). Having previously seen the work as part of the Berlin Bienniale in a derelict building in Kreuzberg, the experience of seeing it again transferred to Manchester was all the more relevant and reverent of its place in time and space, given the city’s history in the development of Socialist thinking. As a young man, Friedrich Engels was sent to work in the textile industries in Manchester, and his exposure to the inequality of wealth and standard of living had untold influence on his later writings with Karl Marx.

The film speaks elegantly of the present moment, yet is rooted in a lost time, pondering the predicaments of wisdom and experience. Collins works with a simple premise, asking what happened to the three women who taught Marxist economic theory in the schools and universities of the GDR. Collins focuses closely on their faces, the pores of their skin and details of their features visible, as they tell the stories of their past lives and their transition out of middle age. The interviews are effortlessly synced with archive material celebrating socialism, showing classrooms scenes from pre-1989 educational videos. The work engages with subtlety the problems of defining an era during it and after it. It intelligently raises questions about how we can be acutely alert to the factual historical events of such a significant period, but be uncertain in their meaning and their relation to our present existence. The interviews portray, for those on screen, a sense of living through something important that has passed, and for the viewers, the work relates how the present undergoes reevaluation. marxism today (prologue) (2010) is accompanied by a second film, which is situated in front of wooden school desks for visitors to sit and watch. The film pulls us forward, into an unknown again, providing the perspective from young German students, who were given a lecture on Marxist economics. The film asks, what does the future hold? What is now like to live now? What do we want for our children? Our grandchildren?

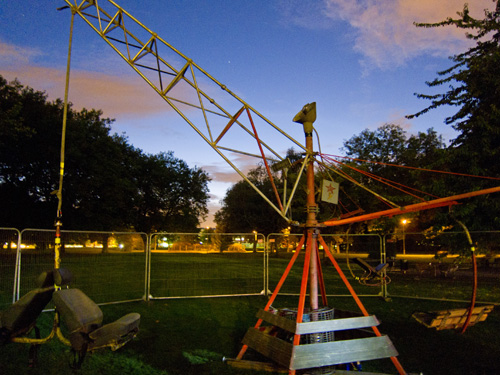

Strolling through Manchester’s Whitworth park, there was a surreal moment, knowing what I was encountering but feeling as if I was the only one in the park that knew that there was something more going on than what might at first be evident. Scores of freshly released school children crowed to get a go on a strange fairground contraption. Enticed by loud RnB anthems, their shirts untucked, they spun in quizzical (semi) delight. The unsafe looking device sustained a slightly giddy atmosphere, as children took turns to ride and watch their friends. The junkyard style device known as The Liquidator is the culmination of a project by a collective who go by the name Plan C, made up of among other people, Eva and Franco Mattes aka 0100101110101101.org. The decaying metal structure is constructed of parts taken from the town of Pripya near Chernobyl. Its ramshackle and post-apocalyptic aesthetic more than makes up for any doubt in the authenticity of it origins. Drawing obvious inspiration from films such as Tarkovsky’s The Stalker, the scene of the ride in the park conjures a sense forbidden tension, the ambiguity it arouses makes you question if you are on the inside looking out, or the outside looking in. An uneasy anxiety remained with me for the duration of my time in the festival.

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s solo show at the Manchester Art Gallery titled "Recorders" came across as a playground of interaction and fun, with a latent hint of the darker side of surveillance and ubiquitous computing. The show contained new and old work all looking at capturing and representing the data of the participants. The exhibition containing classic works such as Pulse Room (2006) was shown alongside a new commission, People on People (2010) which despite its scale and spectacle of mirrored faces and movements failed to hold most beyond the novelty of having your image projected 10m high.

As with the inaugural festival in Liverpool last year, AND in Manchester contains some gems, but doesn’t always live up to the sum of its parts. For what is essentially a simple call to look afresh at the world around us, in our physicality, and in our engagement with technological and identity, Abandon Normal Devices makes it clunky and unclear at times what it is trying to achieve. Shouldn’t all good art seek to question normality? The festival manages to realize a complexity in its message that takes devotion and investigation to comprehend and unravel - however, once you get there, with many of the works, you do leave with an odd sense of pleasant unease.

Peter Merrington is an artist and writer currently based in Liverpool, written with assistance from Katy Merrington and Nicola Singh.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bP7fb1qE34g

Wearing Gillian, Meadows, 2010 (Still)