Zach Blas is an artist and writer working at the intersections of networked media, queerness, and politics. His work includes video, sculpture, installation, and design, among other things. He is also a PhD Student in the Program in Literature at Duke University, and writes extensively on the question of art, activism, and sexuality. Zach and I discussed the question of a queer technology and just what queer theory might contribute to the fields of art and technology.

Jacob Gaboury: What is queer technology to you, and how have you previously engaged with this issue in your work?

Zach Blas: Since 2006, I have been working on and thinking through the potentials and possibilities of queer technology. I've taken many different approaches to engaging this topic. I began with a queer sex act, anal fisting. As I started to think about anal fisting through David Halperin's text Saint Foucault, I saw many parallels between the process of this act and the process of video feedback, something I was obsessed and consumed by at the time. So my first work on queer technology - which I wouldn't necessarily call a queer technology - was an interactive video work called The Hole(s) of Non-Teleology. In this piece, I tried to address the relatedness of process as well as the sexualization of technologies in popular culture: the camera as phallus (think Peeping Tom) and the monitor as feminized (as in Videodrome). Making this piece put me more in-tune with the potentials for constructing technologies from a queer political framework.

-->

JG: I really enjoyed this piece, particularly as it engaged with the question of self-reflexive rather than productive uses of technology. It reminds me very much of Leo Bersani's work in Homos and Is the Rectum a Grave?, and it makes me wonder if queer technology might be that which escapes the normative logic of productivity and development. Is a queer technology one that breaks down or loops endlessly; one that is open to infection and other forms of dangerous intimacy?

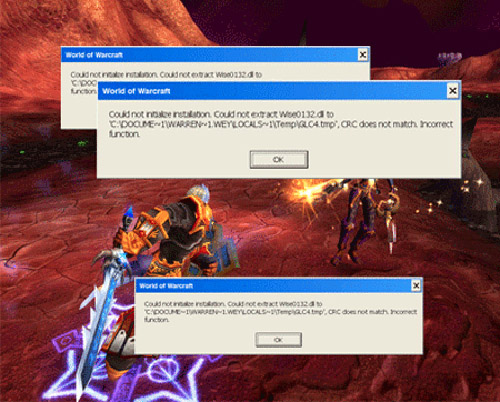

ZB: This was definitely the piece that began to make me think more thoroughly about productivity and usefulness. [In Saint Foucault] Halperin not only talked about [fisting as] the only sex act invented in the 20th century but also as non-teleological, in that it is non-reproductive and non-orgasmic (strictly speaking). I was interested in this idea of queer sex as possibly being non-teleological and I saw a similar non-teleological aspect in video feedback.

So yes, I think sometimes technology has to breakdown in various ways to become political or "useful" to a queer politics. I use breakdown here loosely, as in a general divergence from how a technology is supposed to work standardly or normatively. A breakdown might be a literally breaking down or it might also be a speeding up. I think these creative and political acts of breakdown are the openings to new forms of use, collectivity, desire. I am reminded of Wendy Chun's point about how there is never a purely technological solution to a political problem. Also, Giorgio Agamben has talked about making things "useless" to become political. I think Queer Technologies wants to work in the interstices of useful and useless, or to find new uses through the useless. Importantly, this is not about deconstruction, it is about use, about doing something, experimenting with new ways of doing and making things happen.

JG: You mentioned your recent project, Queer Technologies. Could you elaborate on that a bit more?

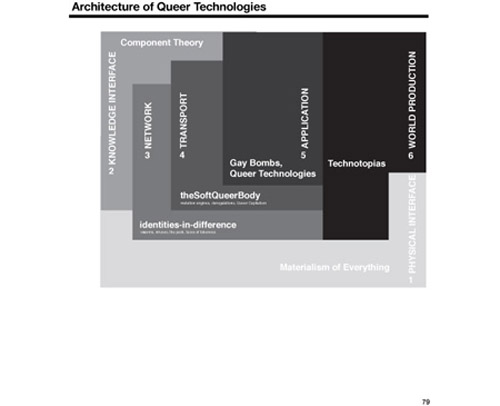

ZB: I began my Queer Technologies project in 2007. Keeping in mind this idea that there is never a purely technological solution to a political problem, I wanted to design technologies that would present alternatives to common technological consumables. I wanted these technologies to offer not only a critique of mainstream technological developments and functionalities but also to gesture toward queer utopic potentials with technology. I've always kept in mind Gilles Deleuze's claim that technology is social before it is technical.

I made transCoder first, which is a Queer Programming Anti-Language. transCoder is designed to not only think through the politics and cultures of programming languages but also to imagine what new things might be forged, communicated, and made through such a language. transCoder is an API, so it's meant to be collectively built and worked with. transCoder is engaging with a history of queer slang language - what Paul Baker calls "anti-languages" - like Polari in the UK. If there is a history of slang language in queer communities, what can be created by producing a queer programming anti-language?

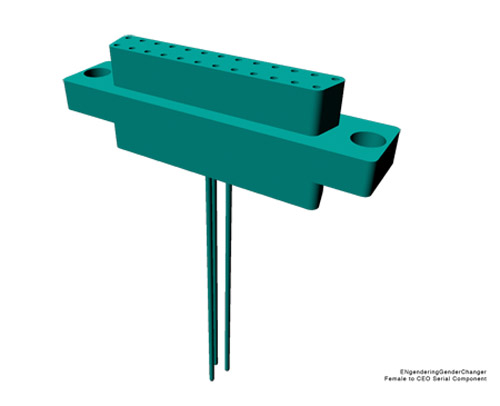

ENgenderingGenderChangers came next. I wanted to create something that could break out of the male / female binary labeling commonly seen with serial adapters. I decided to design a series of "gender" adaptors that expanded beyond male and female, playing with pin and hole configurations as well as various IT stereotypes more broadly. This expansion of ideas, such as Female to Power Bottom, is not to say that an expansion of genders in this context is what we need but to point toward the problematics of conflating gender and sexuality with technology in this way. ENgenderingGenderChangers is also about connections, new imaginaries of queer connectivities. What might these new adaptors enable us to do?

The third Queer Technologies project is Gay Bombs, which is designed as a technical manual. It is meant to be a manifesto of sorts, a guide on how to use Queer Technologies and why. Gay Bombs is a re-appropriation of the US Air Force proposal in the mid-90s of a chemical weapon that would make same-sex combatants of war sexually irresistible to each other. While the military "gay bomb" relies on a public shaming for defeat, Queer Technologies uses this logic to construct networked activist tactics, conceptualizing the gay bomb as a queer bomb, that is, a bomb that has already existed in queer art and culture (see Derek Jarman's Jubilee or The Smiths music video for Ask), a bomb that unites queer communities in a kind of political love under various threats of annihilation.

The last project I completed in this set of works is the Disingenuous Bar. I had become quite fascinated by Apple's Genius Bar and the bizarre mixings of tech support, intelligence, and capitalism. Clearly, the Genius Bar does not offer tech support; it offers something more like ideological support to keep you a loyal Apple consumer. I designed the Disingenuous Bar as a performative platform where people can engage with Queer Technologies. The Disingenuous Bar is more like political support for technological problems.

Importantly, I decided to make Queer Technologies a critical branding project. As I was already thinking through the commericalization of queerness, I was also aware that most people encounter technology as a consumer product. I decided I wanted to play with this: what would it mean to work through commercial queerness and technological consummables? I decided to make Queer Technologies an organization that produces a critical "product line." I opted for what Ricardo Dominguez has called an aesthetics of confusion and what I am currently trying to develop into a viral aesthetics. By making and mass-producing "products," Queer Technologies is able to exist in a variety of contexts without necessarily being identified as an art object. For example, Queer Technologies are shop-dropped in various tech stores, like Radioshack, Best Buy, Target, Walmart, CompUSA, etc. They are also distributed through the Disingenuous Bar, which is commonly installed in galleries, and also workshopped with various queer organizations. While they are products, Queer Technologies are never finished. They are all designed to be collective engagements, to be collectively experimented with. What can they do? What do they do? What might they create for us?

JG: What project are you currently working on, and how does it relate to the question of queer technology?

ZB: I'm working on a few projects concurrently right now. The first one, GRID, is a mapping project. GRID is a reworking of grids of transmission and communication as well as G.R.I.D. (Gay-Related Immune Deficiency), the name briefly given to HIV/AIDS. GRID is a kind of speculative cartography, a way of reconfiguring space with Queer Technologies. GRID may map out where Queer Technologies are currently located in various cities and towns or it may map out how Queer Technologies would like to remap / infect capitalist flows. This sounds abstract, so concretely, it's a dynamic mapping project that manifests in varying ways--from prints to posters to an interactive application that is in development. I'm also developing a project loosely called Fag Face that deals with faciality, interfaces, and escape. Some people have not heard this phrase, but growing up in West Virginia, I heard it a lot. Telling someone they have fag face is a powerful claim upon another. There's a hint of biological determinism to it: because of how your face looks, someone can determine you're a fag. I've been thinking about this in relation to Deleuze's claim that if human beings have any destiny it is to escape our faces. What would it mean to escape the claims of fag face? Do we, as queers, want to? I'm developing this project around an interface application and a photographic archive. That's as far as I've gotten with it.

I'm doing a lot of other theoretical work now too. Besides writing on viruses and a viral aesthetics, I'm also thinking about unhuman politics (from Eugene Thacker), affect and political love, and the explosion of work on escape, disappearance, invisibility, and nonexistence (Tiqqun, Galloway & Thacker, Emmanuel Levinas, Paul Virilio, and many others).

With all of this new work, [I am] still thinking about how can we reconfigure technology to communicate with the desires of a queer collective politics and build upon that.

JG: I've also been fascinated by the function of disappearance and being made invisible as a political gesture in an age of ubiquitous surveillance, biotechnology, etc. That said, it seems that disappearance is somewhat at odds with an overtly queer project, or at least with identity politics. In order to hold claim over one's identity that identity must be articulated and made visible, but in making it visible we open ourselves up to power, the market, and capitalism (and the kind of gay consumerism your work on branding seems to critique). How are we to reconcile disappearance with a politics of identity?

ZB: It seems to be that queerness used to be a refusal of a solidified identity, that queerness was that which remained radically open and unable to pin down in any specific way. We saw this with the debates over whether someone commonly referred to as straight due to sexual practices could or could not be referred to as queer. Just think about Eve Sedgwick and her position as a white woman with a husband writing on queer men. Queerness has always had a foggy ambiguity, but queerness has also been used within various identity politics for various political struggles with goals of clear-cut visibility.

Today, there is something about the word queer that falls flat. The word has been taken up in so many marketing contexts that queer has, in a sense, become another marketing niche. Of course, there is work going on against this; we can approach this problem in a number of ways. I'm particularly interested in thinking about queerness alongside invisibility, nonexistence, disappearance, whatever being or singularity, however contradictory this might be. I have no idea where this will take me, but I want refusal of any specific identity to come back into queerness. How can we explode queer back into the unknown, the fog, the open? Where might this take us? Deleuze referred to identity as always a legislation rather than a liberation. He wrote of an imperceptibility that kept one open to the multiplicity of desire and the singularity of material existence. I want to think about queerness and imperceptibility, queerness and nonexistence, queerness and disappearance, because I see the potential for something new, radical, and open - a potential for a different queerness for a different time.

JG: There exists a great deal of scholarship going back decades, particularly in the field of Science and Technology Studies, which deals with the question of gender and technology. I'm thinking of Donna Haraway, Sadie Plant, Katherine Hayles, etc. Yet to this day there seems to be little work done on the issue of sexuality and technology, why has queer theory been slow or resistant to move into this field?

ZB: There's been plenty of writing about sexuality and queerness, but I think queer theory has been occupied with other topics and concerns when it comes to technology. But you do find snippets of it here and there, new and old. Technology and sex or technology and sexuality have been dealt with more on the terms of fetishes or various radical sex practices, rather than thinking about how technology comes to bear on formations of sexuality today...this is clearly a wide-open area to engage with.

JG: What then might a queer technology studies look like, or what might be an example of queer technology?

ZB: I think any course on this would need to look at queer, feminist, and gendered histories of technology and computation. Judith Halberstam's text on Alan Turing, “Automating Gender,” as well as Sadie Plant's Zeros + Ones seem like important texts for this. I think other forms of queer technological resistance are necessary to engage with: Micha Cardenas & Elle Mehrmand's collaborations come to mind as well as Ricardo Dominguez's conception of invagination. The electronic distance theater has written about their transborder immigrant tool as a queer technology. They are expanding the idea of queer technology by focusing on the multiplicitousness of the "trans" in transboder, transgender, transreal, transspecies.

JG: Is the term "queer" appropriate in dealing with the question of technology? What does queerness mean to you in this contemporary moment? Might "non-normative" or "resistive" serve similar goals?

ZB: Whenever I show or talk about my work, the question of “queer” always arises. I always get a variety of support and critique: Here are some of the critiques: queer is over, that's so 90s identity politics, cyberfeminists have already done this work, your work is great but why use the word queer.

It's not so easy to use the word queer now. With the commodification of queer, homonationalism & homonormativity, queer doesn't immediately seem to hold up the radical politics it used to; but "seem" is the important word here.

Whenever I'm thinking about the word queer and how/if I want to use it today, I always think back to this point Michael Hardt made about democracy. He says that when writing about such a complex, loaded, troubled, mis-used/mis-understood term, one can do two things: create a neologism, which of course brings with it new sets of problems, or one can stick with the word and intervene into it, bring the term back on track, argue for the power and force of the term. When you do this, you keep the history and struggles around the term. This is what Michael Hardt has done with democracy.

So even with all the criticism, I want to use queer, building upon all its histories and struggles, and critically and aesthetically work with where the term is today. Jose Munoz's new book Cruising Utopia is an amazing example of the vitalities of queerness.

I find non-normative unappealing, in that one of queerness's normativities to me is its reliance on the normative/non-normative. The same goes for resistance. I like what Alex Galloway and Eugene Thacker say about resistance being a Clausewitzian mentality. Resistance is too dialectical for me. Non-normative and resistance seem too closed for me. I like the confused, messiness of queer. I still find radical politics and utopic desires and potentials in it.

JG: What is at stake in formulating a theory of queer technology? What other fields, theories, or ideologies does it engage with?

ZB: I like to think that theories of queer technology are contributing to an expansion of queer theory. Liz Grosz has an amazing essay on the futures of feminism; she talks about how feminism today needs to attend to other questions today, such as those of ontology and the nonhuman. Queer theory also needs to attend to these other questions today, questions of nonhuman materiality, for example, or graphic design, branding, or various technologies.

Eugene Thacker has called for an unhuman politics - that today political thought needs a concept of life for its unhuman dimensions. I think creating theories of queer technology is one way to address this issue of the unhuman and expand queerness beyond the purely human or human-centered. And following Thacker, I think queerness must be thought with the human and nonhuman together.

JG: Thanks for a fascinating talk, Zach!

Lovely work, very cool. Challenges with exuberance while pointing out a key heteronormative feature of the technology industry.