Within the pages of Digital Folklore Reader, Olia Lialina, one of the book’s editors, refers to a claim by the social media researcher Danah Boyd, that some American teenagers identify as Facebook and others as MySpace—preferring a conformist and clean interface persona, or a rebellious and visually pimped one, respectively.

This book, co-edited by Dragan Espenschied, is by all outward appearances a MySpace, brimming with exuberant design elements culled from all over the net and reaching deep into online history. The dust jacket repeats a background image of a unicorn perched on a boulder at sunset under a meteor shower. Its reverse is wallpapered in 32 by 32 pixel gif icons representing the gamut of popular user-generated online imagery: cartoon characters, porno ladies, geometric designs, quotidian objects, flags, logos, landscapes and text, from WTF to FREE TIBET. One layer deeper, the cover and back of the book are white, or, probably (in RGB concept), nothing. The spine is also nude, showing off the motley sequencing of pages inside, the first and last of which are a flat, vibrant #00FF00 green, allusive of web-safe color and maybe of a green screen, primed for content to be transposed onto it.

Published by Merz Akademie Stutgart, Digital Folklore Reader is divided into three sections: “Observations” (the core texts, mostly republished essays by the charming, prescient editors), “Research” (insightful student papers) and “Giving Back” (documentation of student projects). Folklore can be considered history told from the perspective of a certain cultural group, and this conception of folklore is precisely what the book endeavors to record. Digital culture involves all kinds of players, including inanimate ones that transmit and present information, and this folklore belongs specifically to users. The fact is writ large, literally, right before the table of contents, in big neon letters spelling out the eerie, friendly question, “DO YOU BELIEVE IN USERS?”

True to the spirit of folklore, from among the nuanced, idiosyncratic accounts and observations that make up part one, there is a repeated narrative that defines the historical significance and instability of users. It is a trauma that practitioners of net art experienced along with all early internet users: digital culture’s abrupt shift from utopia to… something else. And this something else has long since revealed itself to be ordinary. Online terrain, like any other, is ripe for colonization by the corporate mechanics that pilot Western society. It’s hard to predict the future, but it seems that as of 2010 most of these stories are past tense. Users, whose autonomy is already diminished, remain in constant threat of being squelched out like the Na’vi. (A side note in keeping with the book’s multi-tiered, multi-tasking structure: the data cloud directory on page 16 confirms that “Users,” tagged 17 times in the book, and “Money,” 12 times, are indeed the number one and two most frequently occurring keywords.)

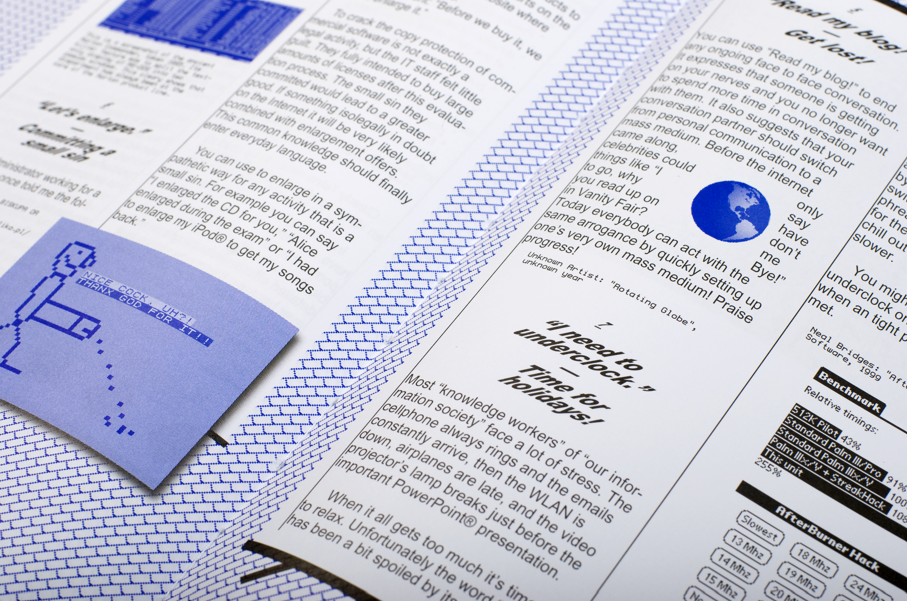

There is a semi-structural, manifesto-ish quality to much of part one, which is both instructive and playful. Text is organized into narrow columns, two per page, which keep a reader’s eyes constantly scrolling. Espenschied’s article “Put yer fonts in a pipe and smoke them,” about the control system that maintains the abysmally limited selection of browser-compatible fonts, is itself rendered in something like handwritten fine point blue marker. This playfulness, and cohesiveness, makes a great vessel for persistent and at times rigorous analysis of online life, which itself has always been rooted in exploration, discovery and excitement, and benefits from complimentary conveyances (especially when things get technical!).

Building upon the contextual foundation laid by the bubble-bursting end of Eden fable (which, I should say, is rarely harped on as such), the essays in part one—including Dragan Espenschied's on online idioms finding influence offline, and Jörg Frohnmayer’s on virtual reality, written in collaboration with Espenschied—linger on other touchstones and tangents, such as Lialina’s provocation in “Who Else is the Cloud?” (2008) that computer culture is underdeveloped because computing power is mainly spent on making computing invisible (no wires, increasingly slimmer machines). She points out that this direction is making people forget about computers. This alludes to a kind of role reversal, in that without a clear vision of the tool used by a user, it is less certain as to whether the user is really the user or the used (that would be: the tool).

Part two, “Research,” features four recent essays examining four contemporary online phenomena and could be read as products of the folkloric tenets outlined in part one. Each is crisp and informed, and their topics— each a bit cheekily pop, to varying degrees—are approached with a pragmatic consideration for history and scholarship. In “I Think You Got Cats on Your Internet” (2008), Helene Dams takes on the trope of the lolcat, seizing on the importance of the funny online kitty lexicon as “a gigantic, global insider joke.” This is an oxymoron that quite profoundly demonstrates the internet’s facilitation of an alternative economy in which content can carry multiple possession statuses at once—as examples: both public and private; or all of individually owned, shared, and free. An insider joke isn’t diminished by infinite insiders (or nurtured by exclusivity). Total dispersion forms social gospel.

This system of abundance and ambidexterity is what marketers study to orchestrate the internet’s capitalistic effects. Specifically they look at user behaviors within the system, which is a subject of Dennis Knopf’s paper “Defriending the Web” (2009). He begins with well-chosen industrial/post-industrial parallels, noting the late nineteenth century philosopher Georg Simmel’s observation that the urban-dwelling (thus more besieged by technology and interfaces) “metropolitan type of man” copes with her surroundings by shifting from a reliance on the heart to “that organ which is least sensitive and quite remote from the depth of the personality.” Knopf relates this to the further stripping away of personality that occurs nowadays when a user constructs an online profile. Further, just as Fordism (mass production—supply courting demand) was usurped by Toyota’s “post-Fordism” (mass production, to-order—demand dictating supply), the author explains how progressive marketers make use of this wealth of indexical personal information to discern what consumers want produced (so that they can consume it, duh). Netflix, with its algorithmic recommendations, is appraised a perfect example of this Sisyphean modern convenience.

Isabel Pettinato’s inspection of viral media’s attributes, uses and historical trajectory, “Viral Candy” (2009), identifies the effective Viral as “susceptible to imitation” by other users, thus proliferative. The essay synthesizes (probably by virtue of part two’s order) ideas about user behavior and economic power structures, touching on aspects of Dams’s and Knopf’s. Pettinato explains how Chris Crocker, the blond, electrifyingly distraught Britney Spears fan “became an Internet celebrity via the dynamics of cultural participation alone," which is essentially an apocalyptic example of the post-Fordist user want-realization machine, in which the commodity that is produced began as and remains a user himself! When the author pinpoints the plot and genre qualities that make for a successful Viral she summons Henry Jenkins’s interpretation of a Cadbury commercial in which a huge Gorilla performs the stirring drum solo in Phil Collins’s “Something In The Air Tonight”. Jenkins states that “[The Viral’s] absurdity creates gaps” (in the words of John Fiske) “wide enough for whole new texts to be produced in them.” Just as with the interior/exterior pleating of the lolcat paradigm, the individual viral video is read to contain an unlimited potential for expansion, based on its ability to open up attentive experiences in an environment carrying a serious attention deficit.

On a lighter note, Leo Merz in “Comic Resistance” (2009) investigates the symbolic significance of the cult font Comic Sans, tracing its origin to a failed Microsoft operating system, and linking its embrace by the electronic music scene to their co-morbid affinity for Roland synthesizers, whose originally intended purpose was also failed. Merz explains that "electronic musical instruments like the Roland and Comic Sans were both conceived as solutions to specific functional needs," and after their services were no longer required, they were repurposed through a transgressive act of abuse, that is ab-use: wrong use—a semantic framework that underpins much of the section’s concluding essay.

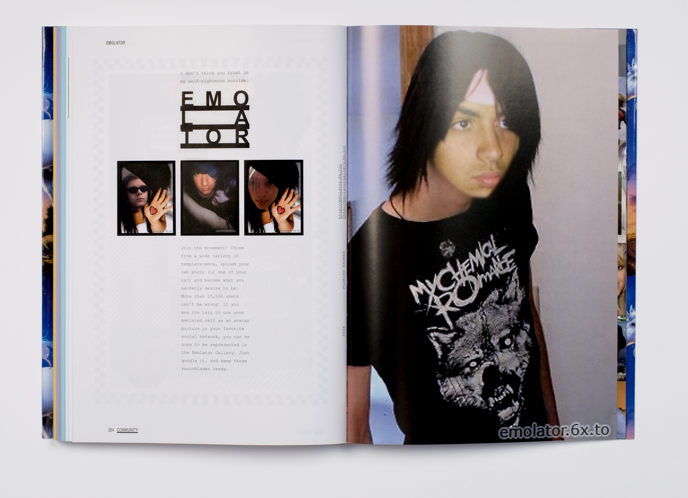

The book’s third part, “Giving Back,” reads more or less as an appendix. It is a sampling of projects made by new media and interface design students at Merz Akademie, presumably under the tutelage of the editors. One work, by Florian Kröner, cleverly titled Emolator (i.e. emo-generator), is a web application that applies template looks consisting of jet black, razor-styled hair, melodramatic body markings, etc., to user-uploaded photos. In effect, while a desired facade is achieved, the self-styled entity in the source image is immolated, amounting to a tight little double entendre. If the project is not particularly moving as an artwork, it does, as do many featured in “Giving Back,” have a prolific life as a user interface, having served thousands around the world.

The users involved with Tobias Leingruber and Bert Schutzbach’s Hoebot and LoveBot (2007) have also been served. Both bots infiltrated online communities of “crazy parties and hot girls” on the German counterpart to Facebook, studiVZ, to conduct a creative anthropological experiment. The former automatically posted misogynistic, beer-oriented comments on the hosts’s walls, and in turn received access to personal data about the girls, along with invites to keggers. The latter utilized the information gathered by Hoebot to tell compatible subjects that they should get to know each other, earning a reputation as a creep and social pariah.

Overall the projects are simple, practical exercises testing many of the topics discussed throughout the book. While in one sense I found the section to be a bit anti-climactic, it is interesting to consider these students as examples of users, in terms of how users have been positioned throughout the book—that is, as active entities, but as ones that are nevertheless subscribed to external protocols (commercial software, website templates, etc.). The students are more or less subscribed to the protocols of their teachers and to the ideas presented in this book. I don’t fault this at all. It’s a further illustration of the compromised but vital role of the user, as an evolutionary figure whose contributions to culture come by tests and trials, rather than mastery and molding. Similarly, Digital Folklore Reader is honest, inventive and comprehensible rather than comprehensive, chronicling what in digital culture is going and gone, while pivoting for the even longer trail of what is yet to be completed.

Kevin McGarry is a writer and curator based in Brooklyn, New York. He is a co-director of Migrating Forms, an annual festival of new experimental film and video, whose 2010 edition will run May 14-23 at Anthology Film Archives.

But where is the part about Gay Rights on the Internet?

where's the free online version?

I could be wrong, but i'm not sure about this word 'user' and it's implication that it is a recent computer based phenomenon.

Sure the term User wasn't applied in this way before, but the situation may have been.

A term like 'User' always naturally implies being used, which always leads the discussion down the same paranoid pathway, that the corporations are out to steal and repackage our individuality at every turn. Even if they do, it's important to remember they do that AFTER the fact, not before.

Anyway.

If you switch the term but keep it's function - consider "ID" as a substitute for "USER", then there is less implication about being used. It would then become more of a discussion about identity, as long standing a human enquiry as that is. It would make discussions of the internet less divine and less short-sighted at least, to me anyhow.

Have their really been no 'users' before the 20th century? Like, if I play the piano, am I not a user of the piano? Should I freak out about the fact that there are only 88 keys to write a song with? Or that all pianos are in the same tuning? C'mon. If having a limited amount of fonts is a problem, what is the solution, handwriting? If you surveyed every person to person handwriting ends up falling in categories and types and families anyhow. Limitations are real, and healthy. Constraint is a force to reckon with. A frame.

Is it really such the unique and compromising position, being a computer user? The term points to a sea of secondary authors, but maybe it is more historic to consider that anyone who even speaks is 'using' an inherited language, with it's own limitations. So what do people do? They invent new combinations and hence new meanings, but they don't invent a new language (esperanto was derivative anyway) if they want to be understood. You take what was before and you expand on it to suit. Everything has always had limitations, it's kind of ridiculous to single out the internet and it's user-generated content as the first example.

I don't want to press on it too hard, and this is just an unedited comment, but does that play?

David,

I really like where you are going with this…

I am also interested in the role language plays in how we perceive and understand the technologies we use and the relationships we have with them. Although I feel like I need to have read the Digital Folklore Reader to really comprehend the reviewer's interpretations (now tempted to spend the money on shipping from the UK!), the review along with your response provide much food for thought….

Perhaps by applying 'user' terminology to our experiences with the internet we are setting ourselves up to be 'used''? Does it also place more emphasis on physical vs. psychological acts of being? When we hear the word 'use' do we first think of the physical, concrete world over an imagined reality? Language can hold us back from meaningful understanding, thus meaningful creative responses to those understandings. Your example of ID as a substitute for user is quite interesting….Now that interacting with computers has become an ubiquitous act to everyday life, maybe we need to alter the language we use to describe these experiences. How might our understanding of these experiences and ourselves change if we were to call ourselves 'participants' and 'players' acting on or within rather than 'users' or 'subjects' of the digital world. Of course, this all relates to Bourriaud's discussion of "relational aesthetics," which actually goes back to Gadamer's hermeneutic inquiry into "play"….

In simpler terms, I am wondering if we need to incorporate some philosophical understanding into our study of these digital devices we use??

In response to your main question, No…being a computer 'user' is not unique when considered within a larger historical context. The problem is that the word 'user' limits our understanding of digital technology to that of the 'user' being 'used' as you have pointed out. Warren Sack, when writing about 'network aesthetics' in relation to art on the internet, wrote that the word 'network' immediately conjures up ideas of a computer so that peoples' minds can not move beyond the concrete technology to think about the abstract relations. I think it's the same thing with 'user'…we think of products, marketing and corporate control and the 'self' becomes multiplied into morphed into digital entities.

I guess after your post I'm left thinking…how can we expand on this language to be understood. I am also very much reminded of McLuhan's notions of technology not only being an extension of the human but being human. Now…we can't just change 'user' to 'being' so, until then, I guess we just need to make work that explores this conundrum…

I am also just playing in the realm of unedited commentary…:)

i want to reply to the importance of this discourse about language, playing, and planing processes in the language of the book:

[img]http://sinnfrei.co.uk/kern/prolog/122.gif[/img]

call it spam perhaps.

Thx Heidi yeah true..

I'm sure it's a good read, as was the review. A text that we are fortunate to have had produced. When I read it will I be a temporary user of it's paradigm?

See also

Wikimedia Commons has media related to: People using computers

Nickname

Home directory

Identity correlation

User profile

The end-user is a concept in software engineering, referring to an abstraction of the group of persons who will ultimately operate a piece of software (i.e. the expected user or target-user).

This abstraction is meant to be useful in information which is believed to be relevant in a specific project.

When little constraints are imposed on the end-user category, i.e. when writing/publishing programs for the general public, it is common practice to expect minimal technical expertise or previous training. This is also the general meaning associated with the term end user (see also Luser). In this context, easy-to-learn GUIs (possibly with a touch interface) are usually preferred over more sophisticated command line interfaces for the sake of usability.[1]

In certain projects where the Actor of the System is another System or a Software then it is quite possible that you do not have an end user for your system. And the end users for the system, which is an actor for yours', would be indirect end users for you.

So in the end, although USE is implied, by that logic we USE everything we interact with. By breathing you are a user of trees. Etc. It can either be retained as a specific computing term (in that it is not commonly 'used' in other contexts) or if it were used in it's broader sense of usefulness, it becomes meaningless in that it applies to almost everything.

Our cognitive limitations may be due to cycling on a fixed term here (USER), more so than it's actuality and historic precedent as a fact of life where everything is part of a system and effectively uses that system. To assume that there was a time not so long ago (ie. before the internet) when cultural production was pure and proto-original (it's a difficult one because in fact much artistic does purport to be….), in that it did not rely upon or spring from a prevalent system is still now as preposterous as it was then.

The internet and software still have a long way to go before they are understood holistically and historically as instruments in the great line of instruments, perhaps it's not as novel a situation as it appears. Yet without doubt, we have certainly again expanded and connected to each other and in turn to what had gone before.

An easy way to begin to understand the limitations of language would be to recreate any critical text in a Microsoft Word document for example, 'using' a Find and Replace action on the term 'user', to then see if it reads differently (swapping for an active term like 'farmer' perhaps over the passive 'user'). I will paste an example of the modified article in the comment below.

However it must be noted that all other terms do not refer so strongly to computer culture as does the term USER, and therefore their substitution dilutes the meaning, into a broader interpretation. I still think this is a good thing. Separation is much easier to discuss than fusion. Both are equally valuable. Especially if we are to transcend the current boundaries imposed upon originality and production within a software centred horizon.

Sometimes I think our base fear of the systems is what prevents us from truly understanding them.

Whether understood as users, surfers, farmers or otherwise - the fact remains that the communicative impulse is one that we have sought to transcribe for thousands of years. In effect it has always been mitigated by feudal systems of power and knowledge centralization for almost as long, save for our much loved and perennial 'outsiders'. Yet, no-one is truly outside the ultimate system of life. If anything, in a time when popular ideas suggest we are more limited in our 'autonomy' than ever before, the notion of language to lock down and define our relationship just keeps failing to cover all those excellent gaps.

Progression is not borne of pure originality as there is none, but of an effective lateral subset?

[size=34]Farming, Farming, Farmed: Digital Folklore Reader, edited by Olia Lialina and Dragan Espenschied[/size]

By Kevin McGarry on Monday, March 1st, 2010 at 06:15 pm.

Within the pages of Digital Folklore Reader, Olia Lialina, one of the book’s editors, refers to a claim by the social media researcher Danah Boyd, that some American teenagers identify as Facebook and others as MySpace—preferring a conformist and clean interface persona, or a rebellious and visually pimped one, respectively.

This book, co-edited by Dragan Espenschied, is by all outward appearances a MySpace, brimming with exuberant design elements culled from all over the net and reaching deep into online history. The dust jacket repeats a background image of a unicorn perched on a boulder at sunset under a meteor shower. Its reverse is wallpapered in 32 by 32 pixel gif icons representing the gamut of popular farmer-generated online imagery: cartoon characters, porno ladies, geometric designs, quotidian objects, flags, logos, landscapes and text, from WTF to FREE TIBET. One layer deeper, the cover and back of the book are white, or, probably (in RGB concept), nothing. The spine is also nude, showing off the motley sequencing of pages inside, the first and last of which are a flat, vibrant #00FF00 green, allusive of web-safe color and maybe of a green screen, primed for content to be transposed onto it.

Published by Merz Akademie Stutgart, Digital Folklore Reader is divided into three sections: “Observations” (the core texts, mostly republished essays by the charming, prescient editors), “Research” (insightful student papers) and “Giving Back” (documentation of student projects). Folklore can be considered history told from the perspective of a certain cultural group, and this conception of folklore is precisely what the book endeavors to record. Digital culture involves all kinds of players, including inanimate ones that transmit and present information, and this folklore belongs specifically to farmers. The fact is writ large, literally, right before the table of contents, in big neon letters spelling out the eerie, friendly question, “DO YOU BELIEVE IN FARMERS?”

True to the spirit of folklore, from among the nuanced, idiosyncratic accounts and observations that make up part one, there is a repeated narrative that defines the historical significance and instability of farmers. It is a trauma that practitioners of net art experienced along with all early internet farmers: digital culture’s abrupt shift from utopia to… something else. And this something else has long since revealed itself to be ordinary. Online terrain, like any other, is ripe for colonization by the corporate mechanics that pilot Western society. It’s hard to predict the future, but it seems that as of 2010 most of these stories are past tense. Farmers, whose autonomy is already diminished, remain in constant threat of being squelched out like the Na’vi. (A side note in keeping with the book’s multi-tiered, multi-tasking structure: the data cloud directory on page 16 confirms that “Farmers,” tagged 17 times in the book, and “Money,” 12 times, are indeed the number one and two most frequently occurring keywords.)

There is a semi-structural, manifesto-ish quality to much of part one, which is both instructive and playful. Text is organized into narrow columns, two per page, which keep a reader’s eyes constantly scrolling. Espenschied’s article “Put yer fonts in a pipe and smoke them,” about the control system that maintains the abysmally limited selection of browser-compatible fonts, is itself rendered in something like handwritten fine point blue marker. This playfulness, and cohesiveness, makes a great vessel for persistent and at times rigorous analysis of online life, which itself has always been rooted in exploration, discovery and excitement, and benefits from complimentary conveyances (especially when things get technical!).

Building upon the contextual foundation laid by the bubble-bursting end of Eden fable (which, I should say, is rarely harped on as such), the essays in part one—including Dragan Espenschied's on online idioms finding influence offline, and Jörg Frohnmayer’s on virtual reality, written in collaboration with Espenschied—linger on other touchstones and tangents, such as Lialina’s provocation in “Who Else is the Cloud?” (2008) that computer culture is underdeveloped because computing power is mainly spent on making computing invisible (no wires, increasingly slimmer machines). She points out that this direction is making people forget about computers. This alludes to a kind of role reversal, in that without a clear vision of the tool used by a farmer, it is less certain as to whether the farmer is really the farmer or the used (that would be: the tool).

Part two, “Research,” features four recent essays examining four contemporary online phenomena and could be read as products of the folkloric tenets outlined in part one. Each is crisp and informed, and their topics— each a bit cheekily pop, to varying degrees—are approached with a pragmatic consideration for history and scholarship. In “I Think You Got Cats on Your Internet” (2008), Helene Dams takes on the trope of the lolcat, seizing on the importance of the funny online kitty lexicon as “a gigantic, global insider joke.” This is an oxymoron that quite profoundly demonstrates the internet’s facilitation of an alternative economy in which content can carry multiple possession statuses at once—as examples: both public and private; or all of individually owned, shared, and free. An insider joke isn’t diminished by infinite insiders (or nurtured by exclusivity). Total dispersion forms social gospel.

This system of abundance and ambidexterity is what marketers study to orchestrate the internet’s capitalistic effects. Specifically they look at farmer behaviors within the system, which is a subject of Dennis Knopf’s paper “Defriending the Web” (2009). He begins with well-chosen industrial/post-industrial parallels, noting the late nineteenth century philosopher Georg Simmel’s observation that the urban-dwelling (thus more besieged by technology and interfaces) “metropolitan type of man” copes with her surroundings by shifting from a reliance on the heart to “that organ which is least sensitive and quite remote from the depth of the personality.” Knopf relates this to the further stripping away of personality that occurs nowadays when a farmer constructs an online profile. Further, just as Fordism (mass production—supply courting demand) was usurped by Toyota’s “post-Fordism” (mass production, to-order—demand dictating supply), the author explains how progressive marketers make use of this wealth of indexical personal information to discern what consumers want produced (so that they can consume it, duh). Netflix, with its algorithmic recommendations, is appraised a perfect example of this Sisyphean modern convenience.

Isabel Pettinato’s inspection of viral media’s attributes, uses and historical trajectory, “Viral Candy” (2009), identifies the effective Viral as “susceptible to imitation” by other farmers, thus proliferative. The essay synthesizes (probably by virtue of part two’s order) ideas about farmer behavior and economic power structures, touching on aspects of Dams’s and Knopf’s. Pettinato explains how Chris Crocker, the blond, electrifyingly distraught Britney Spears fan “became an Internet celebrity via the dynamics of cultural participation alone," which is essentially an apocalyptic example of the post-Fordist farmer want-realization machine, in which the commodity that is produced began as and remains a farmer himself! When the author pinpoints the plot and genre qualities that make for a successful Viral she summons Henry Jenkins’s interpretation of a Cadbury commercial in which a huge Gorilla performs the stirring drum solo in Phil Collins’s “Something In The Air Tonight”. Jenkins states that “[The Viral’s] absurdity creates gaps” (in the words of John Fiske) “wide enough for whole new texts to be produced in them.” Just as with the interior/exterior pleating of the lolcat paradigm, the individual viral video is read to contain an unlimited potential for expansion, based on its ability to open up attentive experiences in an environment carrying a serious attention deficit.

On a lighter note, Leo Merz in “Comic Resistance” (2009) investigates the symbolic significance of the cult font Comic Sans, tracing its origin to a failed Microsoft operating system, and linking its embrace by the electronic music scene to their co-morbid affinity for Roland synthesizers, whose originally intended purpose was also failed. Merz explains that "electronic musical instruments like the Roland and Comic Sans were both conceived as solutions to specific functional needs," and after their services were no longer required, they were repurposed through a transgressive act of abuse, that is ab-use: wrong use—a semantic framework that underpins much of the section’s concluding essay.

The book’s third part, “Giving Back,” reads more or less as an appendix. It is a sampling of projects made by new media and interface design students at Merz Akademie, presumably under the tutelage of the editors. One work, by Florian Kröner, cleverly titled Emolator (i.e. emo-generator), is a web application that applies template looks consisting of jet black, razor-styled hair, melodramatic body markings, etc., to farmer-uploaded photos. In effect, while a desired facade is achieved, the self-styled entity in the source image is immolated, amounting to a tight little double entendre. If the project is not particularly moving as an artwork, it does, as do many featured in “Giving Back,” have a prolific life as a farmer interface, having served thousands around the world.

The farmers involved with Tobias Leingruber and Bert Schutzbach’s Hoebot and LoveBot (2007) have also been served. Both bots infiltrated online communities of “crazy parties and hot girls” on the German counterpart to Facebook, studiVZ, to conduct a creative anthropological experiment. The former automatically posted misogynistic, beer-oriented comments on the hosts’s walls, and in turn received access to personal data about the girls, along with invites to keggers. The latter utilized the information gathered by Hoebot to tell compatible subjects that they should get to know each other, earning a reputation as a creep and social pariah.

Overall the projects are simple, practical exercises testing many of the topics discussed throughout the book. While in one sense I found the section to be a bit anti-climactic, it is interesting to consider these students as examples of farmers, in terms of how farmers have been positioned throughout the book—that is, as active entities, but as ones that are nevertheless subscribed to external protocols (commercial software, website templates, etc.). The students are more or less subscribed to the protocols of their teachers and to the ideas presented in this book. I don’t fault this at all. It’s a further illustration of the compromised but vital role of the farmer, as an evolutionary figure whose contributions to culture come by tests and trials, rather than mastery and molding. Similarly, Digital Folklore Reader is honest, inventive and comprehensible rather than comprehensive, chronicling what in digital culture is going and gone, while pivoting for the even longer trail of what is yet to be completed.

This is fascinating stuff, Ry. I thought I had myself set up to be notified when replies were posted here…guess not. I still need to read through the "farmed" version of the text above for the full effect but needed to let you know that we're on the same wavelength and I like how our discussion has progressed.

Re: "The end-user is a concept in software engineering, referring to an abstraction of the group of persons who will ultimately operate a piece of software (i.e. the expected user or target-user)…"

A couple of years ago I was involved with co-designing and co-teaching a "Human Factors" course in a communication design program. The idea was to have it split between an instructor with usability experience (designing products for Microsoft and other recognized companies) and an instructor with experience teaching visual perception and communication concepts, which would be me. The main project in the course was to develop a "product" considering the full "end-to-end" experience. Now, my background is purely fine art, however, at this point I had been teaching colour and visual communication concepts within a couple of graphic and electronic design programs at this school. When I signed on to develop this Human Factors course, I was just beginning a PhD in art education, reading all sorts of curriculum theory, getting into philosophical hermeneutics, etc. My fellow instructor didn't really understand why I would question the application of a User Centered Design (UCD) or question where she was pulling all of the terminology from. The idea of a course that tried to "round out" and perhaps "disrupt" a "user-centred" approach to design sounded interesting on paper, but it turned out I didn't have enough time to actually split the class and ended up only teaching a few sessions. I actually got excited about getting students to critically analyze the language used in product design (we spent half a class discussing what a "user" was and having them get more into the psychological and sensory experience of their users/participants/viewers/readers). My approach was perhaps more conceptually creative than what the program director originally had in mind (not sure).

Re: “In certain projects where the Actor of the System is another System or a Software then it is quite possible that you do not have an end user for your system. And the end users for the system, which is an actor for yours', would be indirect end users for you.”

Love this…It’s complexity theory and relational aesthetics, all combined into one.

Re: “Sometimes I think our base fear of the systems is what prevents us from truly understanding them.”

I think this is essentially what McLuhan was trying to say about our understanding of technology. He argued that we need to recognize that technology is in fact an extension of the human body, an extension of ourselves. In recent writings, Richard Cavell has applied this theory to digital communication, reiterating a significant point from McLuhan’s often undervalued theories - in any communication, it is the sender who is sent.

With my own work and writings, I am interested in how digital technology might prevent or enable us to better understand ourselves…but it seems the task is for us to first understand the reflection of ourselves within the technologies we use to communicate with one another. If you can know of creative works out there that address any of these ideas, I would love to know about them. I’m building an archive to refer to in my research and writing and am inviting people to email me or post to my blog http://heidimay.wordpress.com/.

Reflective Space: Feeding into Ourselves

I’m searching for interesting contemporary works/projects that use the internet (specifically social media) as a tool for generating information/knowledge about either its viewer/participant/user (individual or community), or perhaps challenge this notion. I am particularly interested in artists that are combining online technologies with self-reflective practices (either self-reflection of the artist or self-reflection of the viewer/participant/user). Also interested in non-digital works that explore these ideas.

Such works might relate to:

Eduardo Kac

Nell Tenhaaf

Perry Hoberman

Olia Lialina

Stelarc

Evan Roth

Rachel Perry Welty

Any ideas? Please share…

http://heidimay.wordpress.com/2010/01/16/reflective-space-feeding-into-ourselves/

Heidi,

You might take a look at my years in the making lookingforlucia.com It isn't quite finished, but you will get the idea. Mary

Thanks Mary….I did take a look….would be great if you could email me some info on your project (via my webpage listed in my profile).

Also…

As I wait patiently for my copy of Digital Folklore, I found the preface of the book (http://digital-folklore.org/) to be a helpful resource related to the above conversation between Ry and myself. Seems key to understanding where the authors of the book are coming from…

Heidi