Rhizome’s key archive of born-digital art, the Rhizome ArtBase, was initiated in 1999. Accepting open submissions which were lightly moderated, the ArtBase grew over the years to hold more than 2,300 artworks.

To “hold an artwork,” though, is a matter of some ambiguity. Many of the pieces in the Rhizome Artbase are dependent on external resources, such as legacy software or externally hosted files, in order to be accessed in a meaningful way.

Beyond this, the ArtBase has an unusual structure. In discussions with artists, Rhizome Founder Mark Tribe realized that many artists would not want to deposit copies of their digital work with a New York-based non-profit, and he developed a model of “cloned” works, which were fully copied, vs. “linked” works, which were merely described in ArtBase and remained under the stewardship of the artist–at least for as long as they cared to maintain it. Interestingly, this kind of approach reflects some of the ideas that have been articulated more recently as part of the discussions around post-custodial archival approaches.

Any tour of the ArtBase has involved broken links, browser plug-in problems, and any number of other issues. Improving access to this unique collection has been a topic of serious research and discussion for two decades. For those interested in this history, check out “Preserving the Rhizome Artbase” (Richard Rinehard, 2002) and “Digital Preservation Practices and the Rhizome Artbase (Ben Fino-Radin, 2011).

In 2014, Dragan Espenschied came to Rhizome as Preservation Director with a singular vision to radically rethink preservation and access to the ArtBase. His argument was that because of Rhizome’s large collection and modest resources, we should focus primarily on techniques and models that could be scaled to address large numbers of artifacts. Over time, this philosophy sparked the programs that Rhizome has developed surrounding Emulation-as-a-Service and web archiving. These open-source software tools and practical approaches have had a significant impact across the field of digital preservation.

Beyond problems of technical access, the way that artworks are catalogued has also been an area of inquiry for Espenschied. On first glance, this might seem like the most straightforward part of the ArtBase–after all, libraries and museums have been cataloguing artworks for many years. However, existing software infrastructure available to the cultural heritage sector for these purposes is in many ways poorly suited to the needs of new media art and net art.

In 2016, these issues became the main focus of a collaborative doctoral project between Rhizome and the Centre for the Study of the Networked Image at London South Bank University led by designer Lozana Rossenova. Arguing that software infrastructure for cataloguing shapes the way in which knowledge about cultural heritage is produced, classified, and shared, Rossenova rethought the entire metadata model for the archive. She notes, “This new model carefully considers the processual, performative and networked characteristics of net art works whose material properties cannot be fully expressed within a few, limited descriptive metadata

Thanks to an NEH CARES grant, Rhizome is in the midst of implementing this model in a new software infrastructure based on the framework of Linked Open Data (LOD), which is part of the broader concept of the Semantic Web. (Also as part of this work, curator Celine Katzman has been improving the artwork descriptions in the ArtBase.)

Linked Open Data is a powerful way of organizing knowledge. It focuses less on describing discrete objects, and far more on the relationships among them — which turns out to be highly apt for the dynamic processes and complex dependencies common to digital culture.

Beyond that, it allows for knowledge to be shared among organizations. From a single search interface, a visitor could easily retrieve results held by any number of institutions using Linked Open Data to catalogue their collections.

For these reasons, Linked Open Data has been a topic of great conversation in the museum and library sector. However, the majority of institutional efforts with LOD remain bespoke experiments, rather than established practice, and primarily only deal with traditional collections, such as Europeana or the British Museum collection of digitized artifacts. More accessible and sustainable infrastructure for LOD in digital cultural heritage does not exist—and so Rhizome, under Espenschied’s leadership, has been adapting Wikibase (the software behind Wikidata, which is the knowledge graph behind Wikipedia) to do just that.

The relaunch of the ArtBase marks a major milestone for our own archive, but also for a Linked Open Data ecosystem for digital cultural heritage. Rhizome’s goal in all of our research is not to position the ArtBase as some kind of definitive final say on the best works of digital art. Rather, we aim to be one archive among a federation of interconnected archives, each with its own focus and support network. To that end, the tools and research that we produce are intended to be useful for other archives, both large and small, and the implementation of Linked Open Data as a viable means for accessing collection data marks an important step toward that goal.

Beyond the question of access, the new ArtBase will also open up the possibility of expanding the archive again, following a period in which Rhizome’s archiving efforts were focused primarily on curated programs. In a future blog post, we will outline new policies for inclusion in the newly relaunched ArtBase.

Over the coming weeks, you can follow our progress on Rhizome’s Twitter and Instagram, and here on the blog, as we prepare the content and infrastructure of ArtBase for this initial relaunch.

This program is supported by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

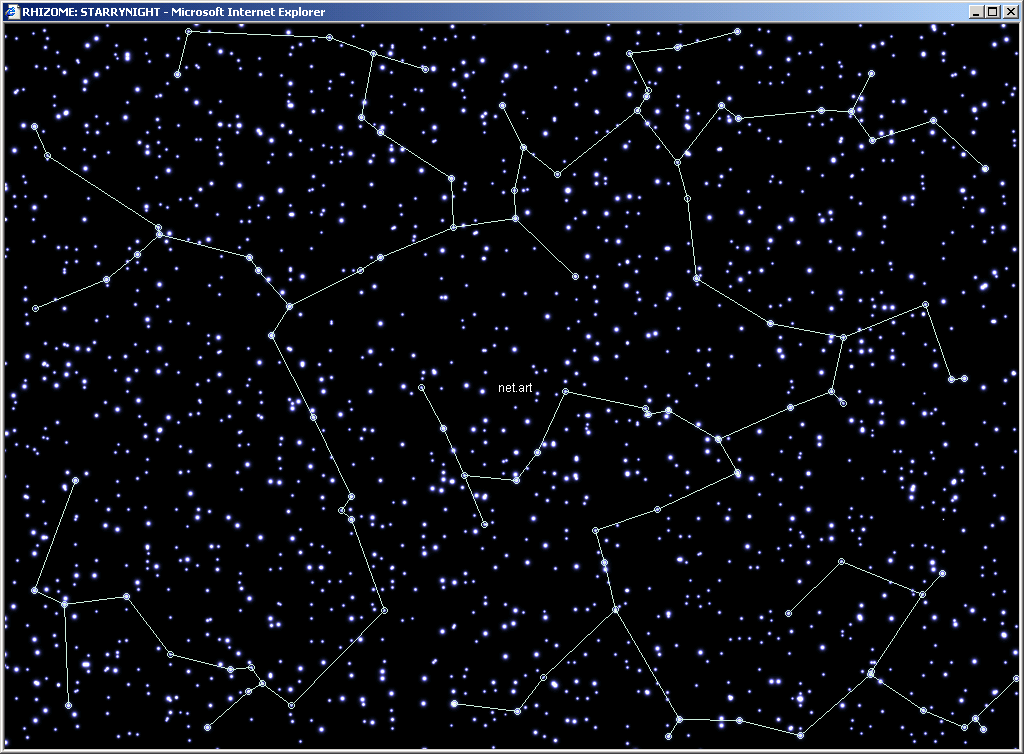

Image: Alex Galloway, Mark Tribe, and Martin Wattenberg. StarryNight, 1999. Screenshot, ca. 2000, Internet Explorer 5.0 for Windows 2000.