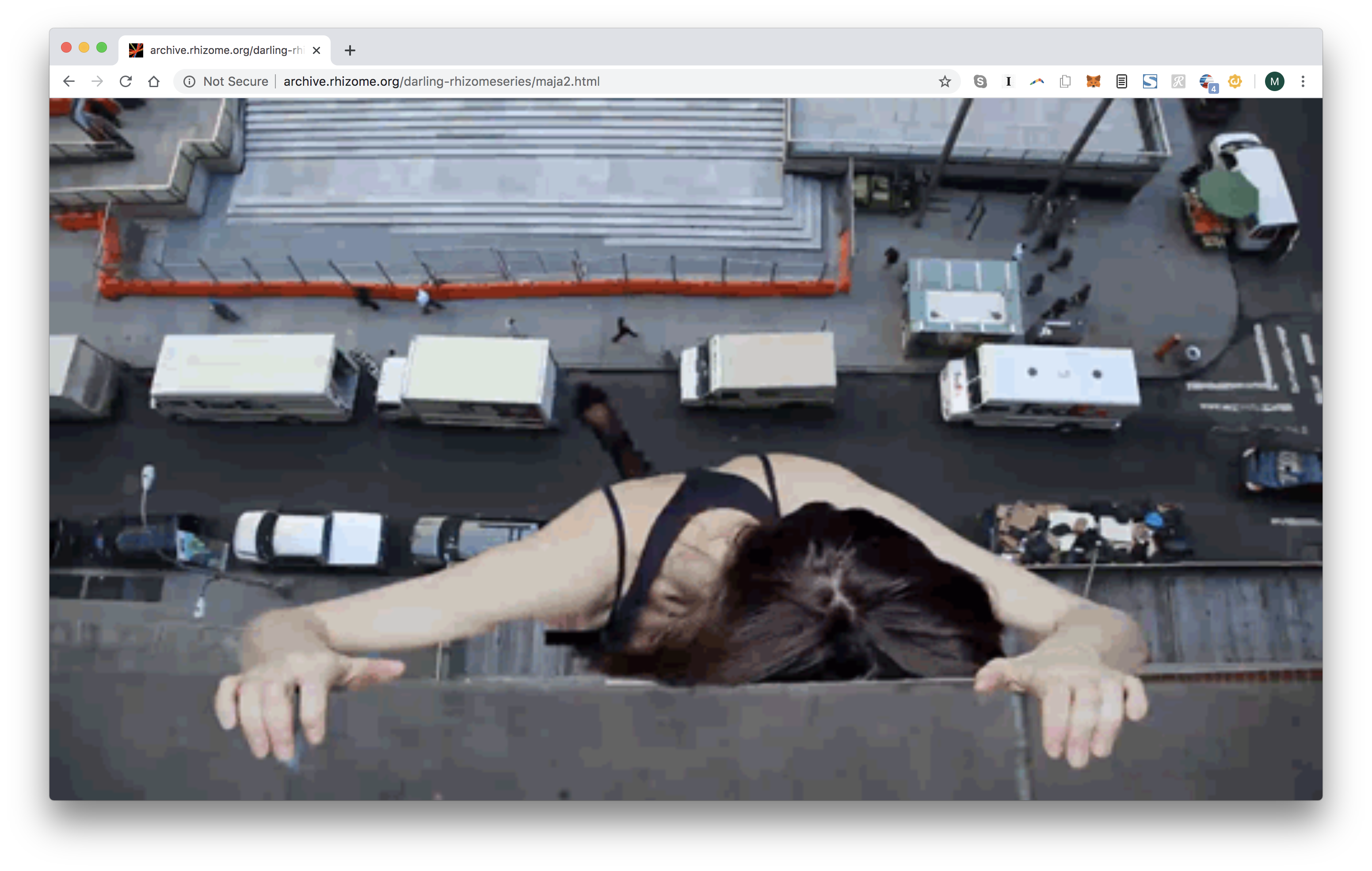

Maja Cule, Hanging from the 8th floor of the South side of The Trump Building at 40 Wall Street, (2013) (featuring: Marlous Borm). From “Performance GIFs,” 2013, curated by Jesse Darling. Screenshot, 2020, Google Chrome v81 on Mac OS 10.12.

With physical exhibitions around the world now closed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, institutions and artists now face questions about online exhibition-making with sudden urgency. The task might at first seem relatively straightforward: to provide a point of access for the general public to programs and information that would otherwise be experienced in person.

For an audience that is sheltering in place, dealing with boredom or hardship or grief or all three, online exhibitions that are presented as stand-ins for a “real,” gallery-centric art experience may only serve as a reminder of a life on hold, inviting direct comparison with the “real” thing, and drawing attention to what is missing from the experience. But online exhibition can be more than a space of simulation, documentation, promotion, and access. While there are legitimate questions to be asked about what kind of online arts programs are needed in a moment of crisis like this, institutions that hope to continue to serve their larger social and cultural mission through online programming during the long international lockdown and beyond would do well to engage in a deeper consideration of the specificities and histories of online exhibition-making.

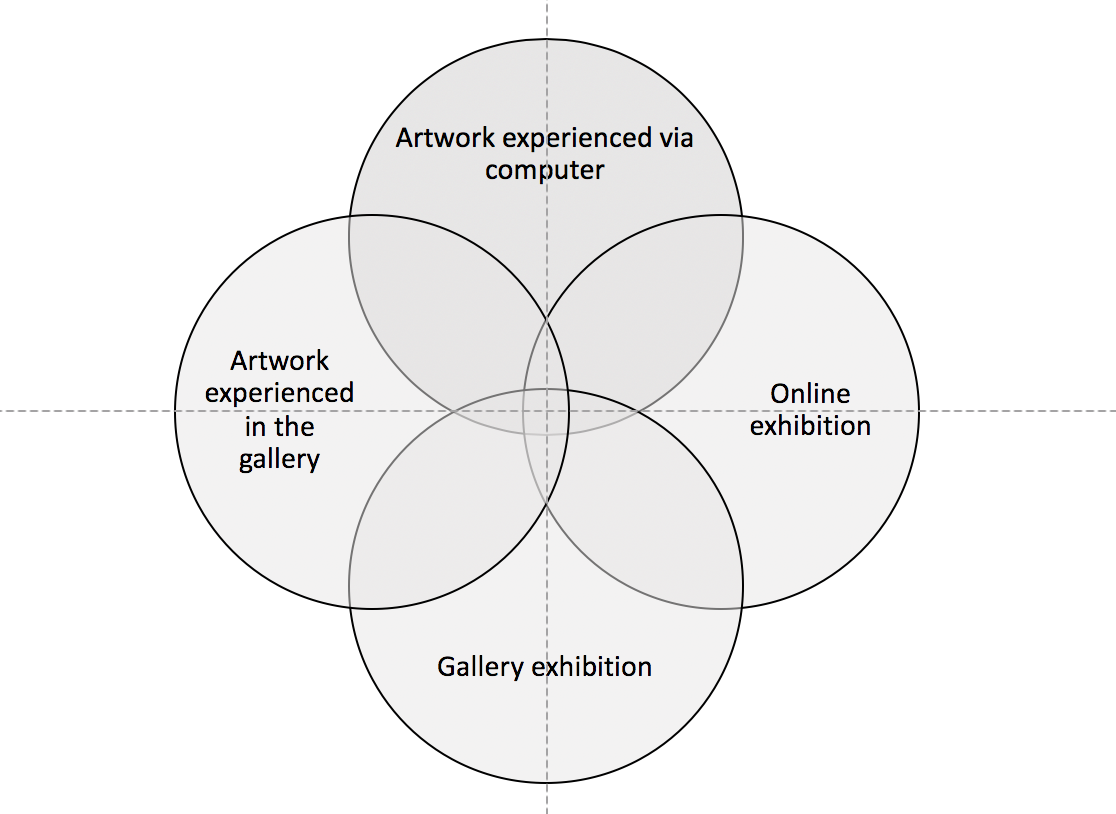

This can be a challenge, though. The histories are not particularly well documented, and the specificities not so thoroughly mapped. In recent weeks, this has begun to change, with online conversations and articles picking up on the topic from a range of angles. In this series, as part of Rhizome’s contribution to this broader discussion, I will attempt to gather some of our in-house approaches to online exhibition-making, while discussing examples from the wider history of born-digital art.[1] In this first section, I’ll argue that online exhibition should be considered as a practice that is distinct from but connected to gallery exhibition, and that the performative, variable quality of born-digital culture is a key aspect of this distinctiveness.

What is an Online Exhibition?

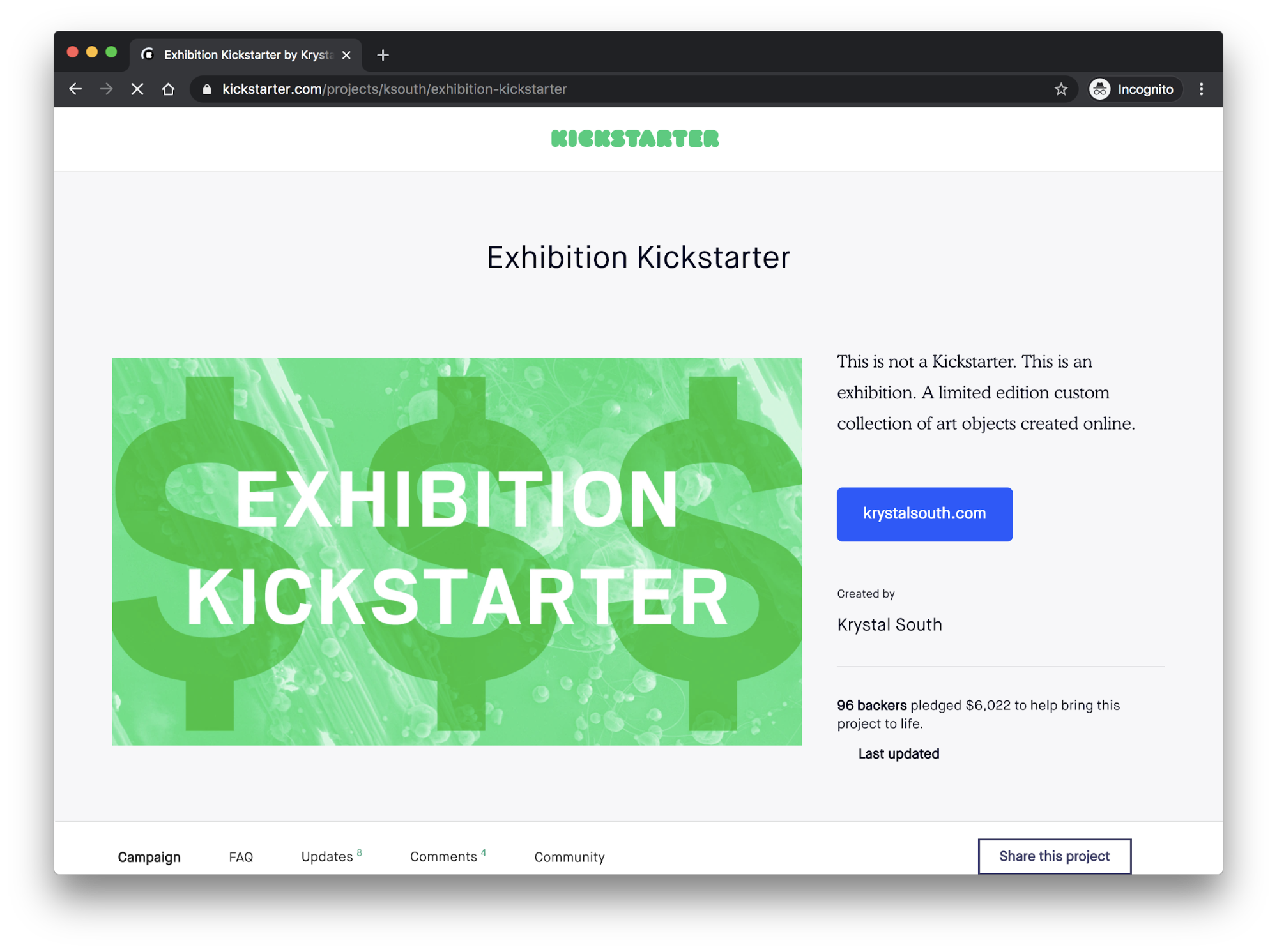

“Exhibition Kickstarter,” 2014, curated by Krystal South. Screenshot, 2020, Google Chrome v81 on Mac OS 10.12.

A crowd-funding campaign offering artists’ multiples to backers.[2] An exhibition in the virtual world of Second Life.[3] A zip file downloaded to a user’s computer.[4] An HTML page featuring thumbnails and links to artists’ works.[5] A curated app offering selections of smartphone-based VR works.

This is a small sample of the bewildering array of projects that have circulated online in recent years under the label of “online exhibition.” While gallery exhibitions have a recognizable default in the white cube, visitors to an online exhibition can expect to encounter any number of structures and formats. At best, this categorical instability allows viewers to understand exhibition-making as a variable, context-dependent cultural practice, and to imagine how it might (or, might not) outlive the white cube – the specific architectural setting to which it was, for a time, largely bound. At worst, it’s just bewildering. Given this gonzo history of experimentation, it is easy to lose one’s grasp on what an online exhibition even is.

In the museum studies field, exhibitions are traditionally defined along lines like these: “Exhibition involves imposition of order on objects, brought into a particular space and a specific set of relations with one another.”[6] Contemporary art has mounted its share of challenges to this kind of definition, but each of these concepts is placed under particular stress in an online context:

- Digital artworks that appear to be coherent objects are rather the performance of objecthood.[7] Digital culture is “more about practices than objects.”[8] Born-digital artworks and cultural artifacts–works that depend on the computer for their creation and reception–can be experienced only when enacted within complex ensembles of hardware and software, and may also rely on audience participation, external websites or media, APIs, or other inputs and services. They are performed, not merely displayed.

- Online exhibitions do not take place in a unified, coherent space. For example, every user has a differently sized screen, so the literal screen space in which the exhibition is accessed is highly variable. The online exhibition may be presented in a navigable, pictorial space, but this is only one organizational rubric among many that may be used to arrange works. Rather than a mere arrangement of works in space, online exhibition involves arranging a multifaceted mise-en-scène to accommodate an unfolding event.

- Specific sets of relations that serve a larger curatorial aim may be often refracted, online, through works that change over time, the input of audiences, the reshuffling of algorithms. Exhibitions as a whole are social processes, and online exhibitions are social processes that play out via computer networks.

With these caveats in mind, the definition could be restated in this way: online exhibition involves the performance of artworks and their objecthood in a particular mise-en-scène, brought into dynamic relationship with one another and a broader network context.

From Physical to Digital

Before unpacking this further, there is an important discussion to be had about the relationship between online and offline exhibition—and likewise, between online exhibition of artwork that is created and experienced via the user’s own computer, versus online exhibition of documentation that refers back to gallery-based work. There is considerable crossover among these practices, and it is not particularly beneficial to worry too much about establishing clear boundaries.

Online culture is often framed as an exceptional world of its own, inherently different from everyday life. It is also sometimes framed as entirely unexceptional, contiguous with “offline” social reality. As scholar Julie E. Cohen has argued, both approaches are limited:

...it is possible to assert that cyberspace is “just like” real space only if one ignores that cyberspace is peopled by real users who experience cyberspace and real space as different but connected, with acts taken in one having consequences in the other. In all cases, theories of cyberspace as separate space give short shrift to cyberspace as both extension and evolution of everyday spatial practice—as a space neither separate from real space nor simply a continuation of it. That is to say, they ignore both the embodied, situated experience of cyberspace users and the complex interplay between real and digital geographies.[9]

Along these lines, the online exhibition is best understood as distinct from and connected to the embodied and situated experience of practitioners, the public, and even the gallery world.

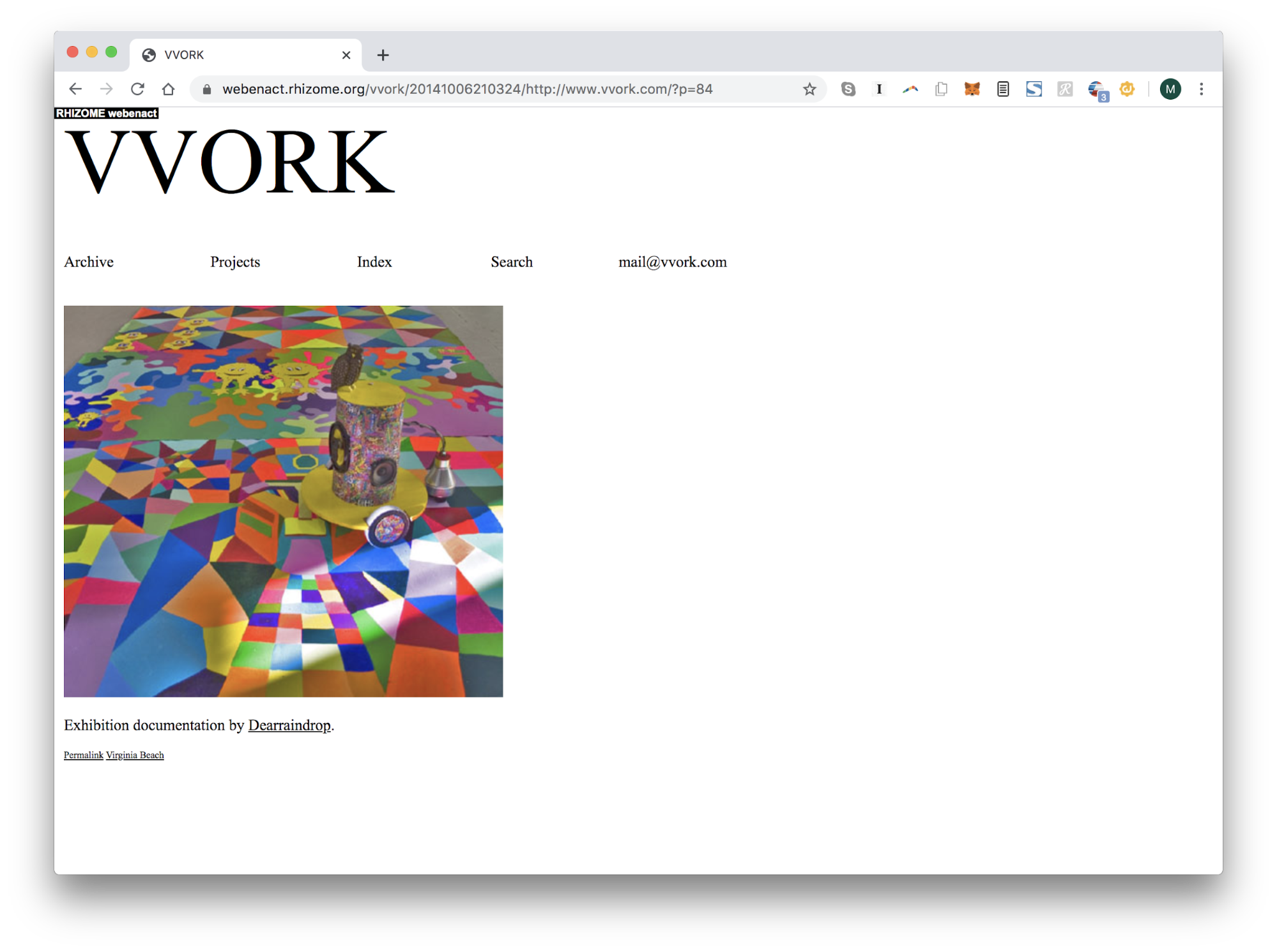

Audiences have long been conditioned to experience physical exhibitions online. In the years before the launch of Instagram, blogs such as Vvork (2006–2012) and Contemporary Art Daily (2008–) built enormous followings for their curated image feeds. While Vvork focused largely on individual artworks, Contemporary Art Daily featured exhibitions, often presenting work from fledgling artist-run spaces from places like Portland and Mexico City alongside established museums. Through these blogs, and the platforms that followed them, users grew increasingly accustomed to experiencing physical work via a screen.

VVORK, 2006–2012. Screenshot, 2020, Google Chrome v81 on Mac OS 10.12.

As gallery visitors increasingly began to make their own photographs of exhibitions for online sharing, gallery architecture shifted in response. Fifteen years ago in New York City, it was still common for a fashionable commercial gallery to use track lighting fixtures or other focused lighting arrangements, allowing the artworks to be brightly lit while keeping the gallery as a whole relatively dim, like a cocktail bar, suitable for a glamorous evening crowd. When photographed by untrained visitors, though, track lighting often resulted in yellowish, murky images, and as the public increasingly began to publish their own exhibition photographs, fluorescent strips offering even, flat light throughout a space became the go-to option.

Ryan McGinley, “I Know Where the Summer Goes,” Team Gallery, 2008 / Ryan McGinley, “Animals,” Team Gallery, 2012.

In this light, even traditional institutions are already engaged in some level of online exhibition-making. Likewise, art audiences are already engaged in online viewership and discourse. On an institutional level, though, online engagement is often formally separated from curatorial work, relegated to a supporting role, and measured according to concrete metrics. This tends to limit the potential for curatorial and artistic investigation of online exhibition in institutional contexts. It’s not surprising, then, that some of the most interesting experiments with the slippage and connection between the gallery and the internet come from artists.

Artie Vierkant’s Image Objects, for example, is a series of panels printed with colorful abstractions. When the objects are photographed for online circulation, Vierkant alters the documentation, creating distinct digital works for online circulation.

Image Object Sunday 17 June 2012, installation view at Higher Pictures, New York.

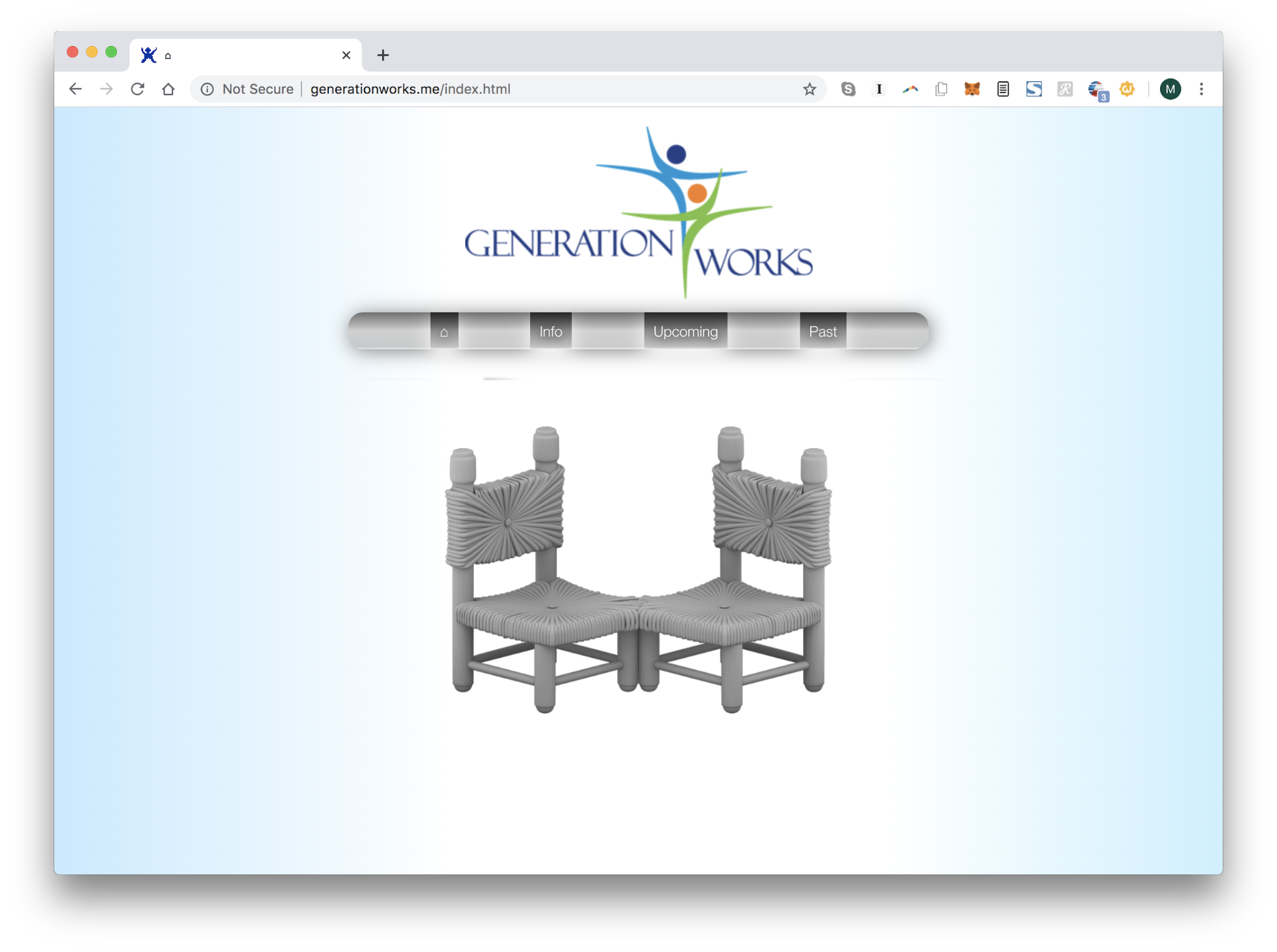

Generation Works, curated by Jasper Spicero, was an artist-run space in a condo in downtown Tacoma, Washington, that admitted no visitors, only making exhibitions available through documentation on an evocative handmade website.

“Generation Works,” curated by Jasper Spicero, 2012. Screenshot, Google Chrome for Mac OS 10.2, 2020, featuring Bunny Rogers, chairs (after Brigid Mason), 2012.

Both of these projects embraced the open-ended meaning-making of the internet, and contrasted it with the authority and fixity of the traditional exhibition space—a tension that is kept alive through organizational structures that delineate online engagement from curation. A full consideration of online exhibition-making as both “extension and evolution” of traditional exhibition practice will have implications for these kinds of divisions, and for curatorial practice as a whole.

If a “rarefied and incontrovertible lingua franca”[10] has been built up over time around museum and gallery architecture, the internet can make that language seem commonplace and open for questioning. Rather than striving to preserve their authority intact in a new context, curators and institutions shifting to online exhibition would do well to begin with an acknowledgement of the “history and wholeness”[11] of the context in which they now work.

Exhibition as Performance

Variability is perhaps the most fundamental and confounding concept involved in working digitally. As articulated in Lev Manovich’s 2001 book The Language of New Media, variability suggests that the same set of data can be accessed in numerous ways, depending on factors like hardware and software environment.[12] Whether an online exhibition consists of documentation of physical work or born-digital work, variability makes the question of what the exhibited work actually is, and how to present it in a stable and coherent way, rather vexing.

Boris Groys approached this topic in his 2008 book Art Power by framing digital exhibition as a form of performance: “The digital image is a copy—but the event of its visualization is an original event, because the digital copy is a copy that has no visible original. That further means: A digital image, to be seen, should not be merely exhibited but staged, performed.”[13] While Groys’s primary focus in this text is gallery exhibition of digital imagery, the same holds true online. Online exhibition involves making certain choices regarding a work’s performance.

Groys places great emphasis on the technical apparatus in which the work performs. In particular, he highlights the curatorial decision as to whether to perform a digital artwork consistently within its original technical apparatus. If the work is shown in its original format, the format itself can begin to overshadow the work. If it is translated into a new format, it may change the work in significant ways. He goes so far as to question whether it is appropriate to include technical apparatus within an artwork’s object boundary:

... to preserve the original technology shifts the perception of a specific image from the image itself to the technical conditions under which it was produced. What we primarily react to is the old-fashioned photographic or video recording technology that becomes apparent when we look at old photographs or videos. The artist did not originally intend to produce this effect, however, as he lacked the possibility of comparing his work with the products of later technological developments.[14]

Groys suggests that overemphasis on technical apparatus can cloud an audience’s understanding of an artist’s original intent. At the same time, though, understanding an artist’s relationship with a given technological context, even down to something as mundane as a specific software interface, might be crucial to any understanding of their intent.

At Rhizome, we use the metaphor of the object boundary to help guide conversations about the role that a given software or network context might play in relation to a given work. In the context of networked software, objecthood is only the performance of objecthood, and the object boundary is not a given, but a variable.

Rhizome’s preservation director, Dragan Espenschied, articulates this as follows. The artifact—the resources such as files that make up the work, which are there even when the computer is turned off—are performed with other resources (usually ones that were not created by the artist) to perform the object. The object boundary includes whatever is considered to be the artifact, plus whatever other resources are brought into the performance.

Decisions about setting an object boundary for exhibition are, at best, subjective and unbound by convention. Should the work be presented in Netscape Navigator 3 running on the cloud, or should we read the source code aloud in a 24-hour YouTube performance?

As part of Rhizome’s online exhibition Net Art Anthology, which focused on historical works of net art, object boundary was drawn in a range of ways:

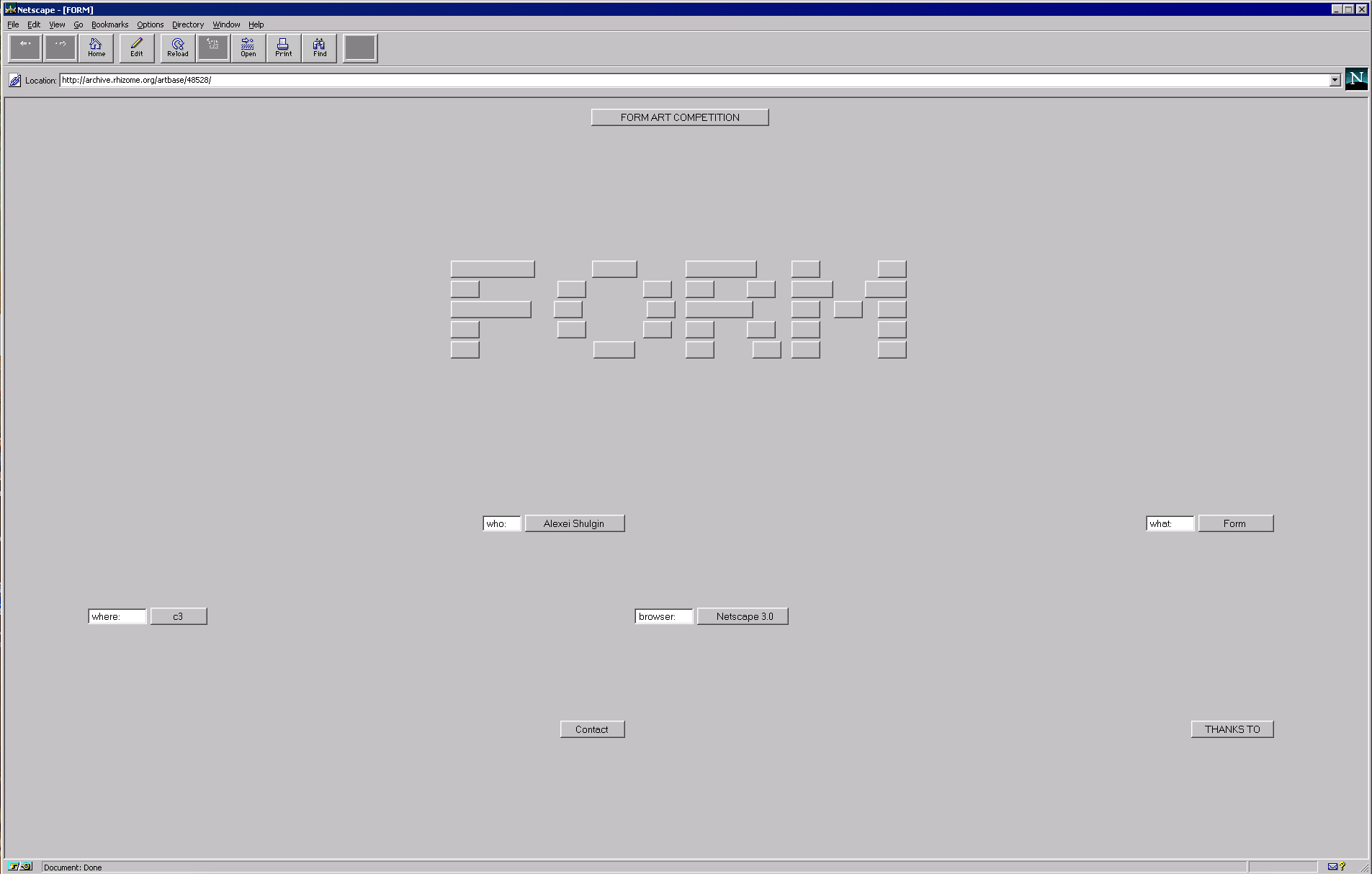

- In some cases, works were presented in a legacy software environment. In other words, the exhibited “object” included both artist-made files and a period-appropriate web browser or operating system. One example of this was Alexei Shulgin’s Form Art, a body of work made up of compositions created using default HTML buttons and menus. A good number of the compositions still render in modern browsers, but the aesthetics of these elements has changed radically from the 1990s to the present day. Thus, Form Art was presented via emulation—visitors to Net Art Anthology can open it in Netscape Navigator 3, running in the cloud.

Alexei Shulgin, Form Art, 1997. Screenshot, 2017, Netscape Navigator 3.04 Gold for Windows.

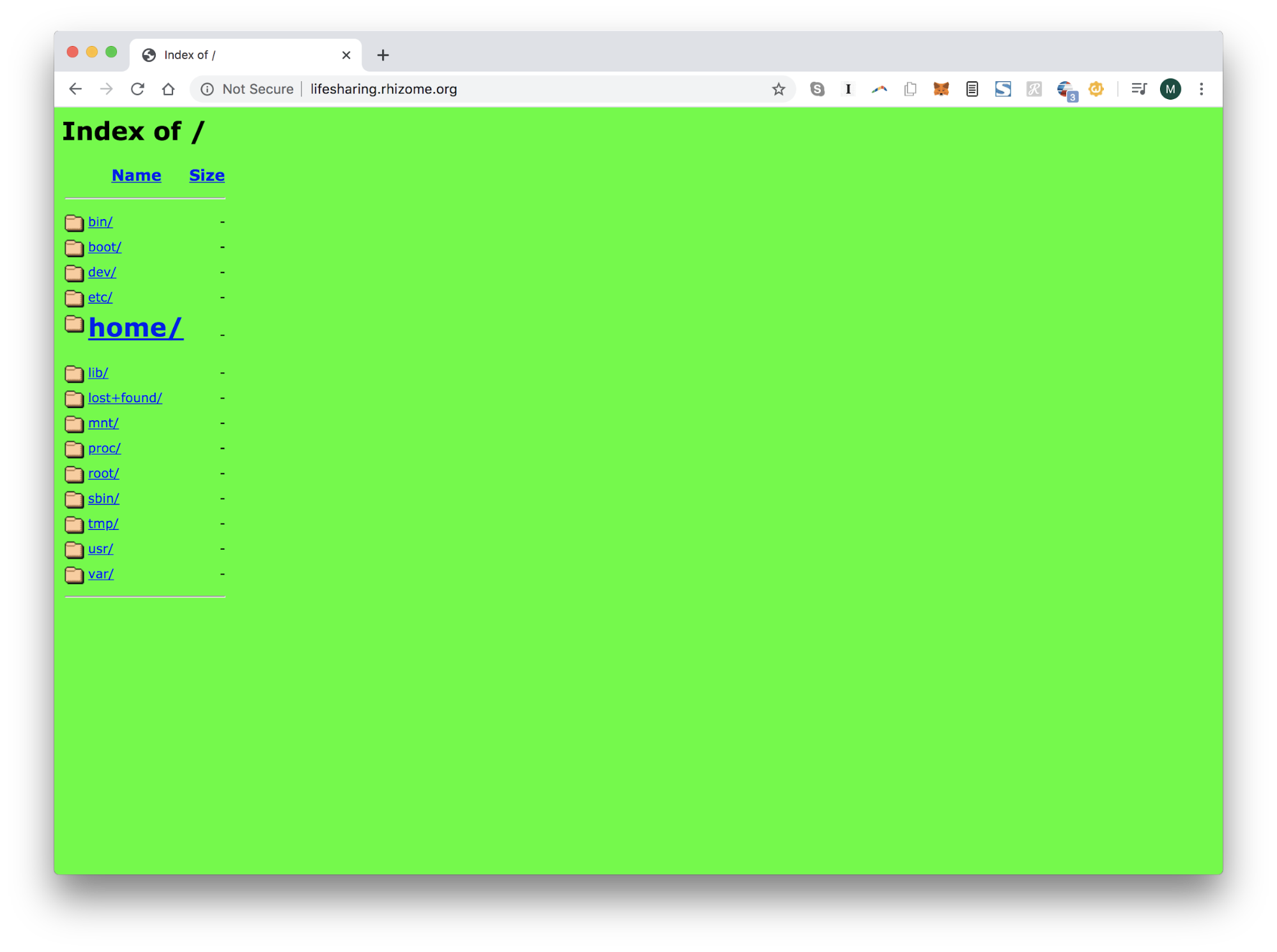

- In other cases, legacy websites were presented in a modern software environment. Life Sharing by Eva and Franco Mattes (0100101110101101.org, 2001–2003) was a long-running performance project in which the artists made the contents of their personal computer accessible online, to the public. During the work’s original life, it changed daily as the artists used their computer. Visitors could check the artist’s email, browse their system files, and view saved images and documents through a web interface. For Net Art Anthology, the original system files were made available as a static archive. If what lent the work its feeling of transgression was the immediacy of accessing a personal computer through the browser; offering access to this work in emulation would add layers of mediation and make this raw personal data more remote. Thus, although there were some aesthetic elements that rendered differently in a modern browser, the work was not shown in a legacy environment.

Eva and Franco Mattes (0100101110101101.ORG), Life Sharing, 2000–2003. Screenshot, 2020, Google Chrome v81 on Mac OS 10.12.

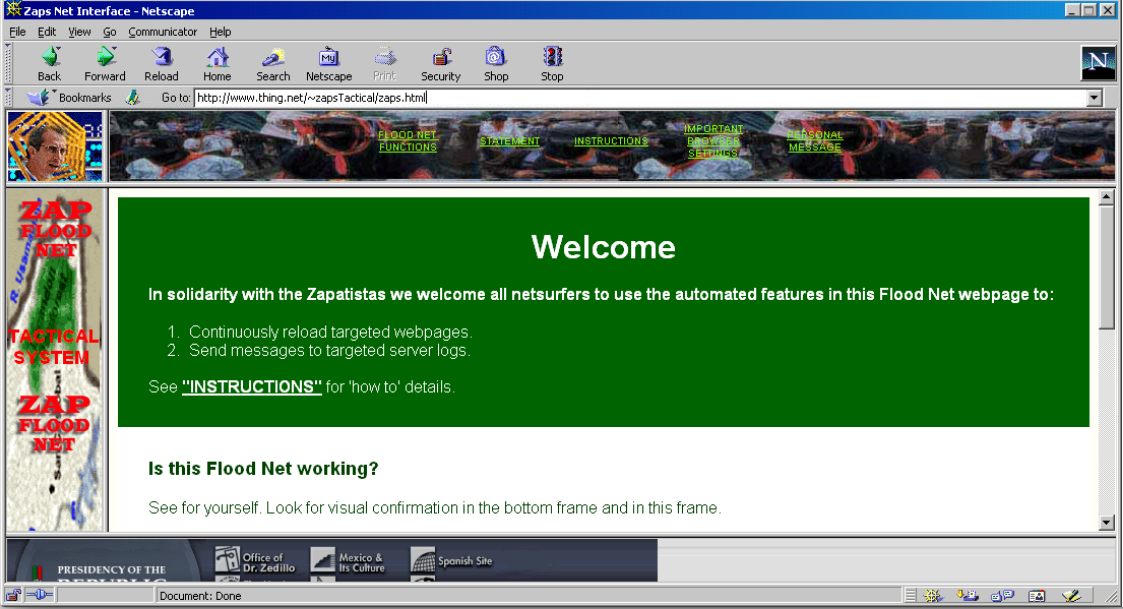

- In other cases, a work could not be presented without some sort of external resource. Electronic Disturbance Theater’s FloodNet was designed as an online protest in support of the Zapatista movement in Chiapas, Mexico, designed as a “sit in” against target websites that represented interests that were opposing Zapatistas. FloodNet used a java applet – a software application embedded in a website – to allow visitors to reload the target pages, thereby slowing them down. The inclusion of this work in Net Art Anthology involved not only offering access to the original work in a legacy browser that allowed it to function, it also involved reconstructing the target websites from saved material on the Wayback Machine.

Electronic Disturbance Theater, FloodNet, website for April 10, 1998 action. Screenshot, 2016, Netscape Communicator 4.8 for Windows. The bottom frame displays a reconstruction of the website of the President of Mexico circa 1998, which was reloaded repeatedly as part of the FloodNet action.

Thus, in Net Art Anthology, some artworks were presented with restored or even recreated elements of their original technological context, but others weren’t. The decision about where to draw the object boundary was made according to the affordances of a given work and what were assumed would be the environments in which the audience would encounter it. This decision sometimes involved input from the artists and curators and preservation expertise, as well as decisions about how best to use limited staff time, and about what artifacts and resources were available.

Regardless of how the boundary is drawn, what results is not a stable object, but the performance of objecthood. As Groys would put it, “each presentation of a digitalized image becomes a recreation of the image.”[15] Each re-staging of an artwork in online exhibition will be new and different and shaped by its participation in a real-time network.

Time to Bang the Bricks

The language of performance turns out to offer a range of concepts that are quite useful for online exhibition-making. In my next installment in this series, I’ll build on this concept to discuss how online exhibition-making can involve mise-en-scène. The concept has its roots in the embodied space of theater, but it has luckily been expanded through its adoption in cinema studies, so that now we can use it without feeling restricted to traditional spatial thinking.

Applying imagery too directly from the physical world to the digital may be hazardous, as my colleague Dragan has pointed out. Such concepts:

…popularize a conservative view on digital culture. When computers are continuously explained with cars, networks with highways, search engines with the human brain, even Email with classical postal service, the actual properties and possibilities of the computer are lost.[16]

Dragan has made a number of suggestions for metaphors that derive from digital culture, but may be used in a wide range of circumstances. For example, he suggests that one can say “I'm gonna bang the bricks” when it’s time to go to the ATM, inspired by the way that Super Mario finds coins by smashing bricks.

I want to expand this metaphor, and to suggest that “banging the bricks” might serve as a useful metaphor for finding value in a seemingly obdurate situation.

When making online exhibitions, it is important to be wary of the conservative tendency to rely on traditional gallery exhibition as sole point of reference. Attempting to replace “real” exhibitions online only remind audiences that they are confined to their homes, deprived of the “real thing.” Replacements invite direct comparison with some now-inaccessible experience of seeing artwork alongside other flesh-and-blood humans. Rather, the task is to explore the online exhibition as a distinctive practice that is still connected to a broader field and history of exhibition-making, a real experience in its own right. To do this, one must bang the bricks.

Notes:

[1] As a whole this text rests especially heavily on the work of Rhizome’s preservation team under the direction of Dragan Espenschied.

[2] “Exhibition Kickstarter,” curated by Krystal South, 2014.

[3] Examples abound, but two notable efforts are the Temporäre Kunsthalle Berlin Second Life, 2007, and Manetas Desert in Second Life, 2008.

[4] The Download was initially a Rhizome program offering artists’ works for download, initiated by Zoë Salditch, and was relaunched and rearticulated as an online exhibition series by Paul Soulellis (2015–2018).

[5] Examples abound, but “Miniatures of the Heroic Period” curated by Olia Lialina in 1998 is a favorite.

[6] Liz Wells, “Curatorial Strategy as Critical Intervention: The Genius of Facing East,” from Judith Rugg and Michèle Sedgwick, Issues in Curating Contemporary Art and Performance, 29.

[7] Rhizome, “Preserving Digital Art with Rhizome and Google Arts & Culture,” meeting agenda, April 2017.

[8] Trevor Owens, “‘Digital Culture is Mass Culture’: An interview with Digital Conservator Dragan Espenschied,” Library of Congress, 2014.

[9] Julie E. Cohen, Cyberspace As/And Space, Georgetown Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper No. 898260, 2007.

[10] Jimmie Tiptree Jr, “Post Whatever: on Ethics, Historicity, & the #usermilitia,” Rhizome, 2014.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media, Cambridge: MIT Press, 2001.

[13] Boris Groys, Art Power, Cambridge: MIT Press, 2008. 84.

[14] Ibid., 90.

[15] Ibid., 91.

[16] Dragan Espenschied, “I gonna bang the bricks!” — I will draw money from an ATM,” Contemporary Home Computing, February 8, 2007.