Aria Dean: What led you to pursue your refresh?

Kristin Lucas: There were many factors. In my previous works, I was sorting through how network technologies were changing the way we live, interact, and see ourselves, and their effects on our bodies and thinking.

In my daily life, I became obsessed with the refresh function of my browser, how it could be used to clear a visual snag on a webpage, or receive an update. I routinely hit refresh in anticipation of improved performance of the same content. I imagined embodying a refresh and what that would feel like, how it could be an effective way to clear up snags in my life, recalibrate, improve my performance, and escape past events that I continued to relive. In my fantasy of a bodily refresh, everything in my visual field, all the information would drop away momentarily before reloading with the exact same information with the potential for a new perspective to emerge, a new outlook onto the exact same information. This change would be refreshing, freeing.

My work is circuitous. A short story I read a couple years back had stuck with me. “Pierre Menard: Author of the Quixote” by Jorge Luis Borges is a story that teases apart notions of authorship. The protagonist rewrites—word for word—chapters of another author’s book and claims authorship because through the process of copying, he lives each of word as if it were his own.

In my backyard, I was casting fake rocks from molds of fake rocks.

There was a pattern in my work of asserting the personal within institutional and technological frameworks that were not necessarily designed to respond to this kind of expression. I had performed characters and fictional scenarios that navigated identity and gender constraints imposed through these frameworks. I once turned an interaction with an automated teller machine into an online therapy session. To evolve my work, I looked for ways to engage with systems more directly.

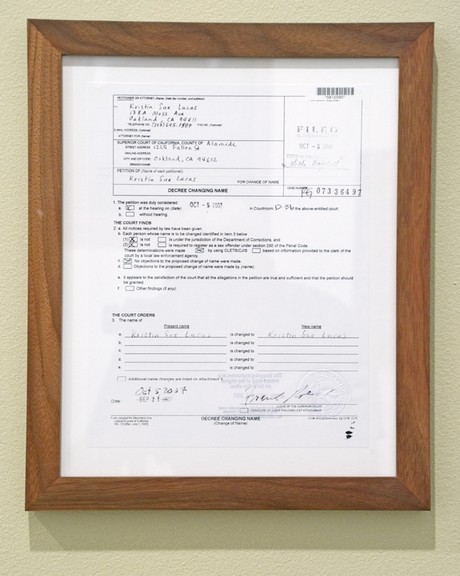

Naming comes with power. Naming is transformative. Naming is a ritual. Naming is a protocol. A name gets to core issues of identity. In the first hours of life, a baby is entered into public record: given a name, a location and time of birth, a family history, and a gender.

According to the law, there is truth in a name. Another way of looking at it, a name is made up, invented my parents or a guardian who performs the role of naming the baby for the law. It is a legal fiction. And this legal fiction is identity-forming. Law requires that identity be stable and have permanence. I may feel ownership over my name but to change my name on public record, I need the permission of a judge. Self-experience tells me the opposite, that identity is unstable, temporal, and iterable. To exercise agency over my identity, I appropriated the name change procedure into a life experiment.

AD: Can you describe the process you went through in order to refresh?

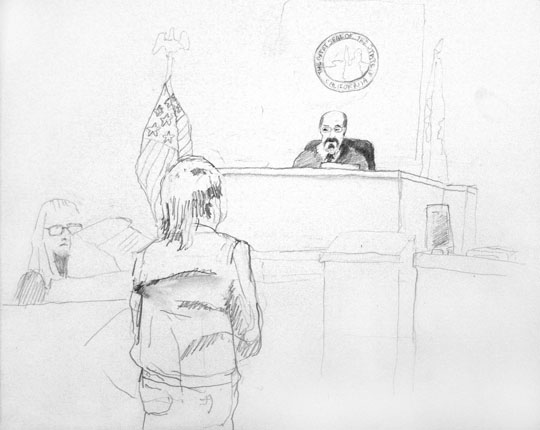

KL: A year of thinking, a day of filling out forms for a name change petition, one-hour spent processing paperwork and paying three-hundred twenty dollars in court fees, sixty-four days awaiting the hearing date, two days spent with friends backing up my life, fifteen minutes jotting down my thoughts before the hearing, five minutes sprinting between buildings after realizing I was at the wrong courthouse, two weeks in limbo awaiting a second hearing to learn the judge’s decision. I wore the same outfit to both hearings.

AD: How do you view the relationship between the original courtroom performance and its re-performance through various readings of the transcript?

KL: I am a trained artist but I chose not to perform as an artist in the courtroom. I preferred the freedom that came with not naming what I was doing. Art was a frame of reference but it was not my only frame of reference, and it was a frame that would introduce distance. I entered the courtroom as a citizen undergoing a life experiment. I activated a plan and worked it out on my feet, unrehearsed. I tasked the judge with solving my existential crisis through the procedure of a name change. Over two weeks, and two hearing dates, we collaborated on changes that could have an effect on us, and the legal system.

The name change process is public so it seemed fitting to share the courtroom ephemera publicly. Refresh is the presentation of these documents and Refresh Cold Reads is an iterative performance that consists of unrehearsed readings of the transcripts by volunteers and guest readers. These readings have taken place in classrooms, on stages, and in galleries; in person, through public address systems, video conference, and over the phone. Each performance refreshes the document. The physical acts of reading aloud and active listening, by participants and audience members, were intended to reanimate the courtroom experience and summon the palpable tension I experienced in the public hearings.

AD: You've said in the past that for the Refresh Cold Reads you assign roles based on the participants' "personal backgrounds." Can you explain what drives those choices? What do you look for in a reader?

KL: Guest readers were invited to perform the roles of ‘Kristin’ and ‘Judge’ based on their personal stories, cultural roles or ‘web-like’ connections. I reached out through social network for suggested readers, and the curators I worked with did the same.

Initially, a guest reader for ‘Kristin’ often had their own name story, had lived more than one life, or had experience working with copies, drafts or versions. A guest reader for ‘Judge’ often held a position of power in which they could influence change. My criteria for casting readers broadened over time, depending on the context of its programming. I got to know the readers beforehand so that I could deliver an introduction before the readings. Our conversations revealed deeper, uncanny, and sometimes humorous connections between readers and the transcripts, and the between the readers who were paired together. Our stories became more interested woven together.

2010 Refresh Cold Read, Netherlands Media Art Institute, Copenhagen, Denmark

AD: Have the different formats for the transcript cold reads - in-person, with phone-in actors, via skype - expanded and shifted its meaning for you over the years? What have these different formats offered?

KL: Over time, I saw the technology as a pivotal performer in the experience of the restaging of my refresh. That said, I didn’t exercise too heavy of a hand over this. These choices were made in collaboration with the organizers, the technological means available at the venue, and the practicalities of distance. The interplay between stories, technologies, and the venues history were punctuated by the method of technological delivery.

Microphones formalize and give a ceremonial feel to the readings.

A cell phone created a disembodied voice that enhanced a layered story about presence and absence in a particular historical context.

Video conference technology situated my refresh in the familiar space of the internet, and introduced artefacts and noise. An outcome was that you had to be an even more engaged performer and listener. The combinations of public address systems and the mics produced an echo. This was particularly uncanny in how it interacted with the personal story of Echo Morgan who was performing the role of ‘Kristin.’