Photograph: Sean Joseph Patrick Carney.

I saw poet Andrew Durbin read in a light drizzle in the backyard of Essex Flowers, a ground-level flower shop on New York's Lower East Side with an artist-run gallery in its basement. Despite the crappy weather, the patio was packed and I felt lucky to be near the stage with a decent view.

Next-Level Spleen (which was published last year in online magazine The Destroyer) took about 20 minutes to read aloud. Durbin's voice began with a casual cadence, his pace quickening during certain passages—not because he was rushing, but because the text required urgency. The poem begins as the narrator gets ready for a movie night (code for sex) with a FWB at the unoccupied apartment of the friend's father. The narrative setup suggests a sort of New Sincerity/Tao Lin-esque intoxicated banal hipster casual romance scene, but breaks that promise when the plotline of Clueless, which plays on loop on a television screen in the bedroom, becomes the central focus of the piece.

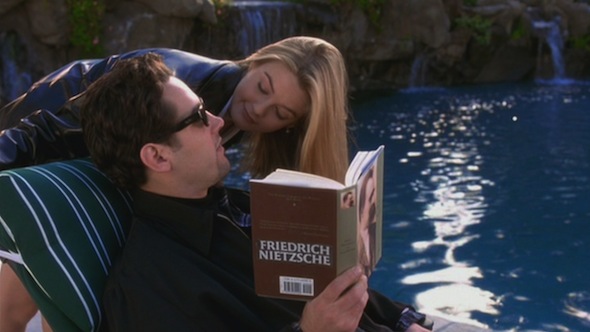

(For readers over 40, under 18 or clueless, Clueless (1995) stars Alicia Silverstone as Cher, a rich, popular high school girl in Beverly Hills, California who falls in love with her unfashionable older stepbrother, played by Paul Rudd. Cher's seemingly shallow and materialistic persona is itself proven only superficial as she sees past the importance of designer labels and social status to recognize the inner beauty of Paul Rudd's supposedly average-looking, but caring, character.)

The lovers ask each other what the film is supposed to mean, giving the narrator the opportunity to draw the listener out of the scene and into an essayistic analysis that proposes Cher as a Baudelaire of Los Angeles consumer culture, a flâneur of great privilege "whose primary objective is to be / carried through urban space without having to engage it / herself." Even the natural aspects of Cher's Los Angeles seem to be a consumerist projection:

The sky is ubiquitous yet culturally specific; its color relies less on place or time and more on how it's branded. Where many poets use fictitious characters or vivid sensorial descriptions to relate the reader to the work, Durbin uses proper nouns pulled from pop culture. (Kyle Minogue's "Can't Get You Out of My Head," Katy Perry, Jay-Z and Kanye West''s "Niggas in Paris", Calvin Klein, MTV, and Michael Bay are just a few of many that pop up within the 1500-ish word poem.) To his mostly young audience, Durbin's brief mentions of celebrities and pop songs carry much more weight than the superficiality they often represent.

When I heard Durbin describe Clueless with these words—

a visionary

force of astonishment and the singular item of cinema that

produced the self I embody today.

—I reflected on how Cher had influenced me as a girl. Clueless made the valley girl lexicon and superficial materialistic persona that went with it so easily relatable and ripe for imitation. The movie came out in 1995, and I vividly remember reciting proudly memorized lines with my girlfriends by the lockers in middle school. It was fun to pretend to be Cher—it was a way to draw attention.

A grimmer vein of romantic comedy was referenced in a John Kelsey article, also titled "Next-Level Spleen," which was published in Artforum in 2012. Speaking of an art world where "isolation has been systematically designed into connectivity," Kelsey likened today's "hyperrelational artists" to movie characters from rom-coms like Friends with Benefits and No Strings Attached. In these films, "the abstraction of the body within the screenlike void of the social is performed by actors who seem to Skype their gestures and tweet their lines, reformatting acting for the windowlike stages of Net space." Clueless seemed aware of its place in the cycle of reference and imitation: it seemed drawn from life in Beverly Hills, which was itself a palimpsest of so many movie fantasies, and it also presented this life in a way that could be taken up and reused by its viewers for their own ends. Nearly two decades later, Friends with Benefits and No Strings Attached were humorlessly distilled from a thousand pop culture stereotypes and jokes, to be recycled in equally rote fashion by their audiences.

So on a rainy night in 2014, exhausted by the irony that pervaded the 2000s yet unsure about how to be sincere, it was Paul Rudd's character that jumped out at me from Durbin's poem. He was normcore before there was normcore, wearing no name brands in Beverly Hills. If Cher used her privilege to stand out in a crowd while doing nothing to change her surroundings, Paul Rudd used his to disappear in that crowd while dating girls who spoke as if they were giving TEDtalks for world peace. In Durbin's poem, Paul Rudd reading Nietzsche by the pool comes across as just another facet of the Los Angeles consumerist fantasy landscape, but at least he stands for something.

"'As if,' Cher says in the film a total of four times to vent contemporary spleen against misunderstanding." Drawing from Baudelaire, Durbin says of spleen that it is a "tendency in the subject to hate the urban conditions that produce alienating economic and social forces, etc." and that it "means nothing." Cher's "As if" doesn't change her underlying unwillingness to engage with the city around her; it becomes a symptom of this disengagement. In Kelsey's article, this refusal is presented in a positive light: "Spleen, that resistant affect which remains when all others have been channeled as productive labor, surrounds networks but won't be put to work in them." For Kelsey, spleen helps us evade a system that enforces constant productivity; for Durbin, it is simply a symptom of great privilege. Baudelaire, he notes, "depended on his mother for financial support."

So when privileged-but-engaged Paul Rudd was briefly mentioned in Durbin's poem, I felt oh so romantic—sitting in the rain and patiently listening to poetry aloud in the backyard of a flower shop whose roses I could faintly smell from a distance. I fought my generational tendencies to check my phone notifications, yawn/roll my eyes, and/or document the experience, trying to focus on a reading whose content was so my generation, yet whose form was so not; it required an attention span more common in the 90s.

Of course everyone who's been to Forever 21 recently knows the 90s are back—not Cher nineties, Paul Rudd nineties. We all want to be poetic, we all want to be authentic, and we don't quite know how. But we can adopt his look, and we can relate to each other, to ourselves, through the shared experience of the screen, deeply connecting through shallow pop culture.