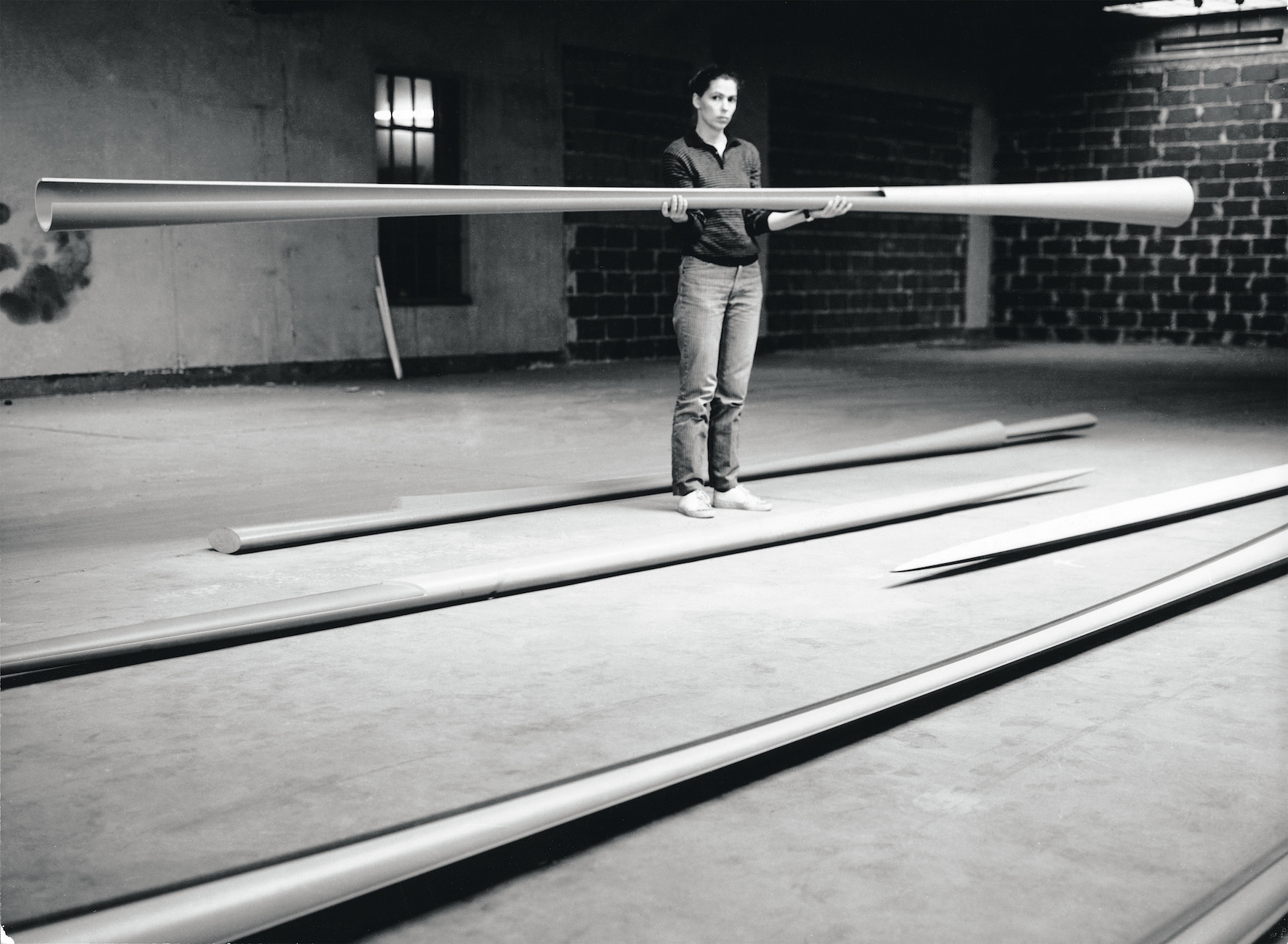

The artist in her studio, 1982. Image courtesy the artist and Galerie Buchholz, Cologne/Berlin.

Upon visiting Isa Genzken: Retrospective at New York's Museum of Modern Art, Rhizome's Community Manager Zachary Kaplan was struck by the relevance of the artist's practice to ongoing conversations that we observe and participate in at Rhizome every day, from her use of technological processes and goods to her deployment of globalized glurge and brand identity. We invited Tyler Coburn and Hannah Black, both artists and writers currently participating in the Whitney Independent Study Program, to walk through the exhibition and weigh in on these valences and connections. In particular, we asked them to keep in mind Rhizome's ongoing discussion of postinternet art (artworks in diverse media, particularly collage and assemblage, that can be seen as responses to a ubiquitous network culture). Their conversation worked both within and against this frame.

Below you will find images of works, excerpts from their chat about those works, and highlights from transcription. To download the whole file for while you walk through the exhibition, click here.

I.

"How could a woman do this kind of work?"

Isa Genzken. Rot-gelb-schwarzes Doppelellipsoid 'Zwilling' (Red-Yellow-Black Double Ellipsoid “Twin”), 1982. Lacquered wood, two parts Overall: 9 7/16 x 8 1/16 x 473 1/4″ (24 x 33.5 x 1202.1 cm) Part one: 5 1/8 x 8 1/16 x 236 1/4″ (13 x 20.5 x 600 cm) Part two: 4 5/16 x 5 1/2 x 237″ (11 x 14 x 602 cm). Collection of the artist. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Buchholz, Cologne/Berlin. © Isa Genzken

The first gallery includes Genzken's wooden floor sculptures: Ellipsoids, which have contact with the floor only at one point in the middle, and Hyperbolos, which touch the floor only on their ends. These mathematically-precise forms were constructed from templates designed on a computer, with the collaboration of a physicist and a carpenter.

TC: One of the interesting things about these works is that, as others have commented, they're Genzken's interpretation of minimalism. [Art historian] Benjamin Buchloh in a 1992 essay noted that, at the time [they were made], Genzken came under quite a bit of critique...for taking on what were perceived to be categories of sculpture that were solely the purview of male artists.[1] The critiques went so far as to claim that these were hysteric treatments of...a certain type of gendered [male] practice.

HB: When you mention that Buchloh thing about people saying "how could a woman do this kind of work?" my initial response is that it's really hard to think of someone making that kind of accusation now. But then I think of the ways in which postinternet is maybe similar to modernism and other kinds of art movements in that it's a boys' club. This was brought up by [curator and gallerist] Rozsa Farkas in the...

TC: ...Post-Net Aesthetics panel that Rhizome organized in October.

HB: She mentions Amalia Ulman, Bunny Rogers, and other artists who are working against that by taking a deliberate, "self-consciously feminized" craft tradition.

These artworks are quite humorous in that way—they're kind of phallic, but lying on the floor in this kind of helpless way. I like that, if people really were saying "you can't do this kind of work because [you’re a woman]."

TC: Another point Farkas made…was that there's been an assumption that deskilling is a necessary tactic for a "serious" critical artist to pursue—that skilling is somehow associated with a medium-specificity that might conjure old ghosts of modernist practice, right? But, in fact—she's looking at Rogers and Ullmann, in this case—skill is attendant to any developmental phase. If postinternet means a proliferation of possibilities of medial practice, on- or offline, it doesn't obviate the possibility, the horizon of skill. It just changes the register.

II.

Networks of information

Isa Genzken. Ohr (Ear), 1980. Chromogenic color print 68 7/8 x 46 7/16″ (175 x 118 cm). Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, gift of Mary and Earle Ludgin by exchange. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Buchholz, Cologne/Berlin. © Isa Genzken

In addition to the floor sculptures, the first room of the exhibition also includes works from Ohren (Ears), a series of photographs of women's ears that were all shot on the streets of New York City. Their subjects are mostly unidentified, but they include musician Kim Gordon and the artist herself.

TC: In a sense, what we are looking at in this room is sound manifest, or different explorations of sound, and implications of sender and receiver…most notably in this transmitter called World Receiver, [which carries] the implication that an audience is being solicited through sound...I like the way these types of sonic wavelengths catch the viewer somewhere within networks of information.

III.

Activating disgust

Left: Isa Genzken. MLR, 1992. Alkyd resin spray paint on canvas 48 1/16 x 32 5/16″ (122 x 82 cm). Lonti Ebers, New York. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Buchholz, Cologne/Berlin. © Isa Genzken Right: Isa Genzken. Bild (Painting), 1989 .Concrete and steel. 103 9/16 x 63 x 30 5/16″ (263 x 160 x 77 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Susan and Leonard Feinstein and an anonymous donor. © 2014 The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Jonathan Muzikar

The second room includes Genzken's Basic Research paintings, oil-on-canvas rubbings of dirt and debris; her MLR paintings ("More Light Research"), photogram-like paintings that are given a distorted, multi-layered effect through the use of perforated stencils, and her concrete sculptures, reminiscent of architectural debris or models of ruins.

HB: I mentioned last night Lyotard’s idea that the job of the artist now is to not create new forms but to accelerate the obsolescence of forms, and that's somehow pertinent to the strategies Genzken uses. You feel some kind of delight in what she works with, but it's also this pushing against the objects or against the kind of medium she's using, as if she wants to be able to discard them, to exhaust them.

TC: In a contemporary context, I feel like so much of the debate, particularly vis-à-vis semiocapitalism and the attention economy, is about accelerationism as one proposition for where we need to go—or, [alternatively,] slowing down of or seeking strategies of duration [and] attempting to reinscribe them into what are increasingly short circuits of attention.

I am curious about how this idea of accelerating the obsolescence of old forms...may or may not be meaningful to contemporary ideas of accelerationism, which (quite candidly) sounds like futurism without the content to me.

HB: I'm going to be dismissive of something I haven't actually read that much about, but I don't find accelerationism that attractive as a concept.

I wonder if there is a problem with these kind of prescriptive analyses of, like, "What is to be done?" that great Leninist question. I guess if you're saying that there's not this kind of prescriptive or programmatic job of the artist to show the way forward politically or whatever, which I think is maybe a slightly crazy claim in some ways... Maybe, then, the job of the artist, if there is such a thing, is to register their own affective relation to the conditions we find ourselves living in. Kind of like anger and perverse exhilaration and, and I think Josephine Berry Slater talks about activating disgust [in Rhizome's Post-Net Aesthetics panel], activating the energy of disgust. I don't know if Genzken quite does that, but there is something of that going on. But maybe we should move onto the more disgusting things.

IV.

Suffering very accurately

Installation view of the exhibition Isa Genzken: Retrospective. © 2014 The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photograph: Jonathan Muzikar. Works from the series Fuck the Bauhaus (New Buildings from New York) are visible in the background.

The next room includes works from the series Fuck the Bauhaus (New Buildings for New York), which marked a major shift into sculptural assemblage, featuring ad hoc constructions of plywood and plexiglas along with consumer objects such as light shades, slinkies, and plastic flowers. Genzken developed this body of work while living in Lower Manhattan in 2000.

TC: In Buchloh's famous 1992 treatment of Genzken, he reconciles her utilization of…commodity goods as stemming from a submission to the terror of consumption under the hegemony of commodity capitalism. Maybe that's not a direct quote. [laughter] In Buchloh's reading, insofar as this is the state of affairs, then perhaps submitting is the only strategy that an artist—a sculptor—can pursue to address or engage these types of systemic issues. So it raises the question…on a practical level: is the only critically viable method one of submission—which seems closer to a form of masochism, right? A submission to a psychotic consumer state. And regardless of that, is Genzken then the exemplar of this form? Is she somehow demonstrating the symptom to the most sophisticated aesthetic level?

And is this notion of submission and the pathologization that accompanies it a) problematic vis-à-vis how Genzken's own history of mental illness is discussed in her work, and b) too fatalistic in its concession to a certain state of illness that seems conditional and systemic?

HB: I actually kind of like this updating of the romantic idea of the artist as the person who exemplarily suffers, or who suffers very accurately or something.

Maybe their symptoms are different from the ones generally experienced, but they display them in a way that's somehow more lucid or something. At the same time, through being completely the opposite of lucid in their everyday personal lives, perhaps.

That Buchloh idea makes me think about how certain subject positions, like feminized or racialized subject positions, are then made to sort of carry the burden of the suffering that can't be allowed to—these subject positions are then almost kind of forced to live out—I mean they do literally live out the maybe more obvious degradations of living in capitalist society, but at the same time, there's a kind of performative function that they're given.

What year are these from? We can go and check it out, but it's just kind of—I mean we were talking before about what a kind of...

TC: 2000...

HB: But it's so interesting they're pre-9/11, which obviously was a very interesting event for Genzken's practice—I'm trying to put that neutrally. But just in the sense of these barely held-up buildings, these kind of parallels—as they are roughly taped together—and it's this thing that might be falling down. How's it staying up? This is the kind of thing she's dealing with a lot of the time. It's just kind of interesting she's already doing the almost-collapsing skyscraper in 2000.

V.

Not cyborg, but not not cyborg

Isa Genzken. Spielautomat (Slot Machine), 1999-2000. Slot machine, paper, chromogenic color prints, and tape 63 x 25 9/16 x 19 11/16″ (160 x 65 x 50 cm). Private Collection, Berlin Courtesy Galerie Buchholz, Cologne/Berlin. © Isa Genzken

TC: So we're moving on to Slot Machine. I wanted to talk about this earlier—the notion of self-portraiture. This work particularly, where she puts a Tillmans image of herself on top of a photo collage, papered over a slot machine, seems incredibly nihilistic in its horizon. Maybe…

HB: You think?

TC: I don't know. What do you think?

HB: Nihilistic in what way?

TC: I don't know. As much as there's…[a] subjectivity conjured through the image-world that surrounds a slot machine, there's also this reductio ad absurdum of the artist—or the woman-as-slot machine, no? I'm riffing off of Hal Foster's point.

HB: It's a joke about vaginas... I find this kind of exuberant... It feels like, "Now I'm going to speak as myself." There's a really nice thing she says in an interview, like, "I'm no longer interested in looking at other people's art. I just want to do my own thing," and I was like, this is the year, a fact from that [Michael Connor] essay, that the iPhone was invented. That was just a fact that I was really struck by. I can't believe the iPhone was only invented in 2007. I feel like I'm still reeling from this newly discovered fact, and then there's the crisis the following year. I thought we could maybe try and tie it together, these new forms of consumption of technology, this generalized internet, that Michael talks about. There's no more postinternet in the sense of after-the-internet because we're always online.

TC: There's no internet culture as some type of delineable space, because so much of our access to culture now is provided by means of the internet. There's no after, there's just during.

HB: Yes, exactly. I'm kind of stitching these things together, but I just like this kind of idea of this final turn towards herself as the register of her work...

TC: But that quote [was from] 2007, wasn't it?

HB: Yeah, so this is a bit earlier.

TC: I think you’re right to reclaim [Slot Machine] from the horizon of nihilism I’m setting it on. I don't have a thorough appreciation of the slot, let's say. [laughter] But...here—and particularly in the x-ray pieces—there's a sense of dependency upon an apparatus for the generation or the registration or the confirmation of an image of the self (certainly not the self). It doesn't feel posthuman or cyborgian in an imagining of a human-machinic interface by any stretch. Nonetheless, she seems to be sensitized both to the conditions of technological reproduction—or technology's reproduction itself—[and] also to affective registers.

HB: I feel like there's some maybe liberal kind of habit, which I fall into myself sometimes, assuming that some kind of authentic selfhood is the good thing, and ... anything that has been evacuated or never existed in the first place is bad. But of course there's loads of ways in which that's untrue and kind of, like, a true gesture, maybe even good politics, to [instead] look at the ways in which the self is already constructed out of fragments of the world and fragments of others and is already radically compromised since birth, because we maybe don't live in a world that is generous with these authentic subject positions we're supposed to be having all the time. So actually kind of like, yeah, I think that kind of point about like, it's neither the cyborg or not not the cyborg is maybe because we kind of are like in that condition anyway. And that is the sort of—I guess that also does happen in the postinternet—

Sorry to be so unspecific. I keep on saying like, "postinternet art" as if that is anything in particular. I guess the idea of a sort of like tragic, I don't know, the kind of melancholic use of the internet, or this idea that the forms are both kind of like, hollow and at the same time all we have cling onto of the affective experience of the world. But I guess, again, I'm thinking of Buchloh which is maybe a little bit limited if that's the only people we mention in this entire thing.

TC: Fair enough.

HB: Mention another person?!

VI.

Love and sabotage

Isa Genzken, The American Room, 2004, installation view Galerie im Taxispalais. Picture: Rainer Iglar

Genzken's room-sized installation The American Room (2004) evokes a corporate office decorated with a series of pedestals bearing sculptural assemblages.

TC: We're walking into The American Room, Genzken's 2004 installation, which seems like a pretty comprehensive critique of mid-noughties American symbolic power. Here, we really see the techniques of assemblage assuming increasingly explicit forms, and a lot of different consumer objects from eagles—which seem as much a Broodthaers reference as a citation of American symbology—[to] Scrooge McDuck and other forms. So I think one thing to consider here, vis-à-vis this postinternet thing, is this is a moment when we can start to see a formal logic that's also operative, say, in [the work of] artists like Nicholas Ceccaldi and Timur Si-Qin—when we find different commodity goods entering into these types of structures. But I think it's important to note that the ends are quite different.

HB: Does she use things repetitively in the same way, do you think? I assume they are mass-produced objects, but I assume she uses them as... they're normally isolated. It's only one of the mass-produced objects. I wonder if maybe those artists you mention are reiterating the same objects.

TC: Signifying the mass-producibility of the good. It's difficult to tell. Certainly in Timur's Axe Effect works, there's an interest in Axe's marketization of forms of pheromonic enhancement, which is to say: you wear this product and you will increase your evolutionary chances of success—of biological reproduction. The marketability of a biologically competitive advantage seems important.

HB: I mean, a completely fictitious biologically competitive advantage.

TC: Of course, though the advertising makes it deeply persuasive. There [in Axe Effect], what you're saying about the reproducibility of the good seems significant. Here [in The American Room]...it's more of a question of...who's being presupposed in the use of materials vis-à-vis the artist and the viewer? One of the points that Jeffrey Grove makes in his essay in the catalogue is that we can look at the turn towards these materials in Genzken's work—to these commodity-objects—as actually being motivated by a democratizing tendency. In a conversation with Nicolaus Schafhausen in 2007 about the Oil exhibition at Venice, [Genzken] also makes a comment that she wants to hold the mirror up to the viewer, and that it would be too cold and arrogant to continue to traffic in rarefied forms, rarefied materials. So for me, that also seems to be a question here. Like, it's complicated to say that the use of the mass consumer good is democratizing, because in a sense, it's a depressing concession that the channels through which we could…realize some type of public communication are these consumer goods—that these might, in fact, be among the more common things that connect us.

HB: It's literally what connects us... these are the marks of human connection; they are not [only] the marks of alienation...they're [also] the means through which we are connected. There's a really nice line in the [catalogue] essay about a world of broken things, and I wonder how much these things are kind of also resolutely unbroken. I really like this very ambivalent use of the commodity, or stuff. I was evoking Evan Calder Williams' very nice riff on objects kind of containing this ambivalence, or containing a kind of self-hatred because of the way they're produced, because they're made in factories, they're made by people who probably hate their jobs. They're like literally the trace of various forms of class struggle and hatred. He's currently working on a project around the idea of sabotage, all the different forms of sabotage. It might take the form of screwing something up, but also it might be done [too well, given that] a lot of factories might adulterate their product because it makes it cheaper. Genzken, you could think of her as a kind of saboteur of these objects, but also in a very loving way. This room is obviously taking a critical look at the iconography of America, but...she uses objects in a way that does seem very irrepressible and enthusiastic and tender, so it's hard to just read it as "screw America" or whatever.

VII.

From the ashes of the Twin Towers, a discotheque

Installation view of the exhibition Isa Genzken: Retrospective. © 2014 The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photograph: Jonathan Muzikar

The final room of the exhibition contains a 2008 series of architectural models and installations that constitute a proposal for the redevelopment of the Ground Zero site in New York, including a car park, a hospital, and clothing store titled Osama Fashion Store (Ground Zero), all provisional structures festooned with colorful consumer objects.

HB: I only found out from reading the catalogue that these are made to the same specifications as the actual architectural brief for the new "Ground Zero." Which does it give it a whole extra layer of interest. I think these are consummately what she does so well—they're very confident assemblages, and they are super-likeable, and work well against the banality of what they're offering, their point. One is supposed to be like a multi-storey car park, proposals for shopping areas...

TC: A discotheque, Disco Soon.

HB: I mean, again, this is one of those places where I don't know where she is with it. Sorry if this is horrible to say, but in a way, 9/11 is like a complete gift for Genzken's practice. She's got this history from Berlin, the destruction of cities, and how buildings are kept up or made to appear to be keeping themselves up. And then she's already very interested in New York. I wondered if for someone who lives in Berlin, New York is then this urban landscape you can read without having to read ruins, without having to read destruction.

TC: Intact, as you put it.

HB: Yeah, it's an intact city. And then 9/11 happens, and it suddenly becomes a way that these things fuse into one. I don't know if she's personally commented on this, or if it's just something that could be periodized in her work in that way. But it's really compelling.

TC: New Buildings for Berlin seems to almost cynically point at an imminent horizon of development in Berlin, and one that very much operates on the large scale of neoliberal capitalism. [By contrast,] what I like about this [Ground Zero] project is that she's inserting herself into the propositional space of reimagining this site—or imagining a continuing but renewed life for this site. And she's doing so on the scale of small business and small infrastructure, right? I think this project represents the most perfect wedding of the types of materials that she's using: the assemblage commodity logic that enters into her work, and the forms of business and forms of industry and forms of service that she's proposing. The material and the proposition come together in a way that suggests…what some curators have described as an optimism, which I feel uncertain about committing to in my own critique, but which nonetheless seems more apparent than in earlier works, like Empire/Vampire or The American Room, that have critical relationships to their topics—whether American militarism or hegemonic power.

HB: So people think they're proposing local small businesses as a critique? Obviously it's not a critique of capitalism, right?

TC: No, I think that they read it as optimism—that here, in Ground Zero, we find proposals for re-use that…adhere more to a Jacobs-esque logic of urban development: small-scale developmental urbanism.

HB: If you look at the great proletarian uprisings, especially recently in London—a city close to my heart obviously—people burned small businesses [as well]. When people want to express how shit capitalism is, they don't just go to big corporate brands. In interviews when people were asked about it they were like, "well, I also can't afford things at my corner shop." It's not that you feel better about things that are locally-run and handmade and organic, whatever. I find this work very sympathetic, and I think you can read it critically, maybe it doesn't even matter what the artist herself would say about that. At the same time, maybe it's problematic that it leaves itself so wide open that you can also read it like "isn't it so great to have new local businesses springing up from the ashes of the Twin Towers."

TC: I might be overdoing that reading. I will say we've been diligent about not calling the curatorial design of the exhibition under review, but regardless of whatever problems I might have with the rooms that preceded, what was interesting to me about this room (when I was first in it and still now) is that the cramped quarters of MoMA actually feel in the service of how these works are installed. Which is to say, there's not a lot of space between them. A room within a private, institutional site has actually conjured…a sense of urban space.

HB: Looking at it again with this idea in my head that these are being presented as architectural models for consideration as part of a competition panel…it doesn't constrain its exuberance to have the works jammed quite close together. Maybe in the other rooms it felt kind of overwhelming. I feel like a lot of the work that has another context, that I really loved in another context and not much here, but I feel very loving in this room. Is that a good note to end on?

TC: I think so. Thank you, Hannah.

References:

[1] Buchloh, Benjamin HD. "Isa Genzken: The Fragment as Model." Isa Genzken: Jeder braucht mindestens ein Fenster: 141.