The latest in a series of interviews with artists who have developed a significant body of work engaged (in its process, or in the issues it raises) with technology. See the full list of Artist Profiles here.

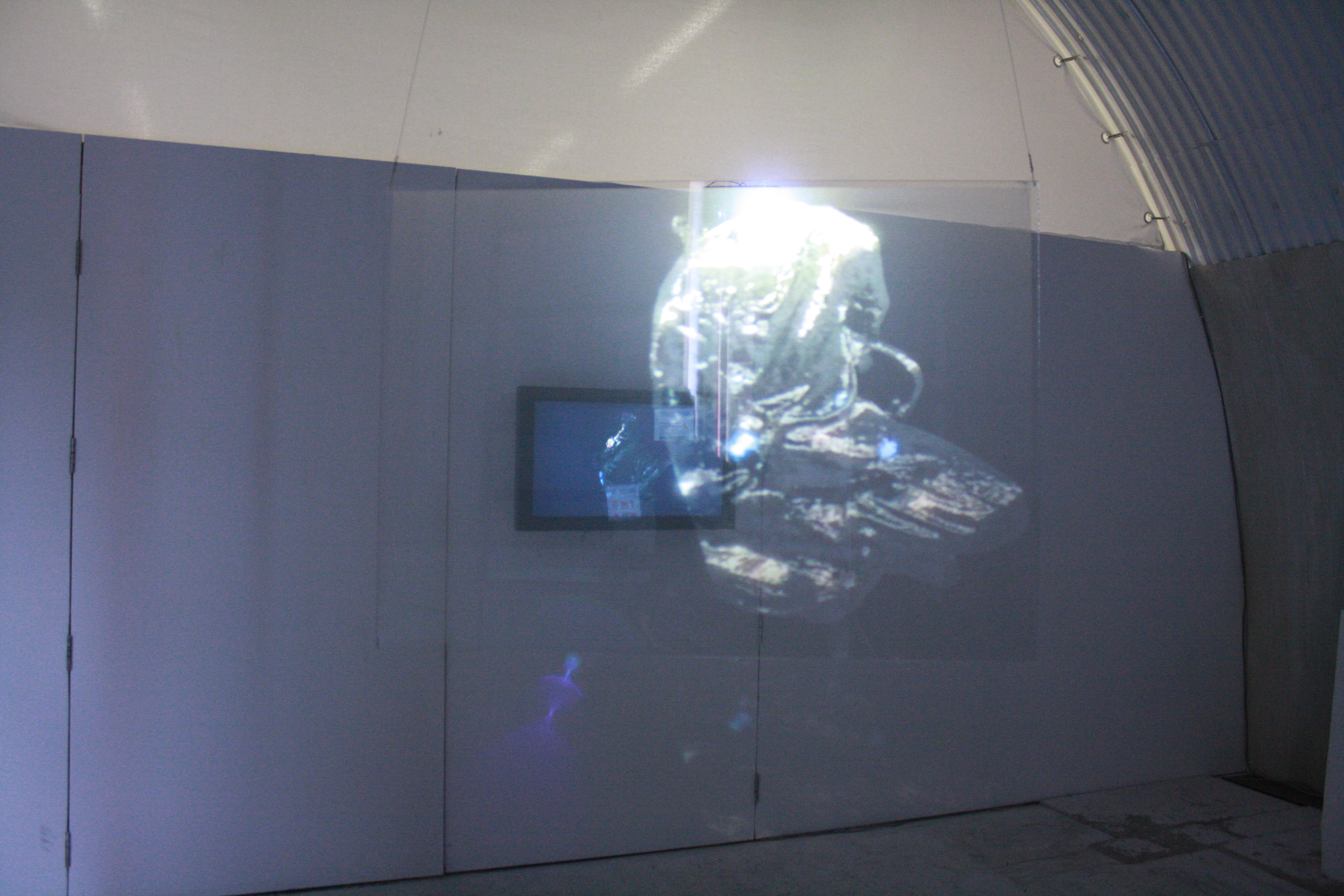

Harry Sanderson, Human Resolution (2012). Installation view at Arcadia Missa for PAMI, London. Digital video, perspex, monitor.

Harry Burke: Your "Human Resolution" project, which you exhibited as part of PAMI last year in London, comprised of a 3D hologram projector and accompanying sound piece, which translated the body of the viewer standing before it into a glitching but uncannily faithful grayscale projection (3D object). It was an attempt to reinsert the body into ubiquitous computing environments, which are too often conceptualized as immaterial, virtual, or idealist, and to re-emphasise the corporeal within the predominantly visual regimes of these technologies. Do you think it was, in this regard, successful?

Harry Sanderson: I think that rather than reinsert the body or to attempt to repair anything, it was an attempt to exhibit a kind of a lack that occurs when something is represented in that sort of way. There is a common conception that images work on a flat plane, for example in a regular movie file, and this was an attempt to show how imaging technologies are moving beyond that into something that actually apprehends physical space. It wasn't just a grayscale projection but it had depth; it would turn and you would see that it understood the contours of your body in a way that's much more physical.

HB: It's an attempt to materialize the space or spatiality of the image?

HS: More the increasing sophistication of cameras and surveillance technology, and that they're no longer just about recording flat planes of colours; they are now cognizant of the distance things are from each other. It goes along with more sophisticated algorithms for interpreting the movement of things which are driven forward by the need for facial recognition software to keep track of people or be able to tell more about a subject from an image of them. This ties into the stuff I'm doing with "Unified Fabric" (opening at Arcadia Missa on October 15th), which includes being able to extract someone's pulse from a regular video file using (Eulerian) video amplification software.

HB: How important do you think it is for an artist to interrogate these technologies as they're being developed in corporate or military environments? For example, the video augmentation technology is a month old, and there's an interest of yours in taking things at this nascent point and attempting to interrogate how they develop, or insert a criticality into their use before it becomes fully codified.

HS: I think when a technology is nascent you're able to see things about it that you won't be able to see when it's become fully integrated. There was an amusing moment a few years ago where one of the X-Men movies was leaked before the effects had been finished. It was this hilarious file because it was these actors acting before green screens—blocks had been filled in but the textures weren't there and there were all these gaps. And it was really interesting to watch the film in that way. It was a disaster for the film because people got to see how bad it was. That's what it's like with these technologies—they're still a bit funky, and not fully slick, so you're able to show them in a way that enables you to see what's happening. And in the flaw of that, in the fact that it doesn't totally integrate or work, there's some capacity as an artist to reclaim a little bit of agency.

HB: This seems like a different approach to an artistic attitude towards technology that's developed in some parallel scenes—artists who hang out at tech conferences, for example—where new technology is much closer fetishized than critiqued.

HS: Personally I'm not so enamoured with the efficacy of these technologies, and their place within global power structures—often materialized as forms of interaction and surveillance. To ignore this strikes me as extremely dangerous. It's straight valorization. Tech conferences seem like a place for just shopping. I'm also shopping, but I'm looking for something beyond that process, which is why the "Unified Fabric" render farm is kind of an odd piece. It's almost like a diagram. It is an attempt to foreground the process of production, and present artworks as part of a chain of production that relies on the consumption of power and resources, rather than existing in an immaterial realm of data and thought. We're building a small supercomputer that will render videos by six artists—Hito Steyerl, Clunie Reid, Maja Cule, Takeshi Shiomitsu, and Melika Ngombe Kolongo & Daniella Russo—with the installation including an accompanying sound piece.

I suppose it's a really tricky position for anything that tries to be politically engaged—the inevitable credibility you give to the objects you take as the basis for your critique. You appropriate technology in an attempt to show it in a critical light but at the same time you reproduce those conditions.

Image: "Rare Earth Production." Published in Harry Sanderson, "Human Resolution," MUTE (4 April 2013).

HB: I think things can be beautiful at the same time as being explicitly political or critical or whatever. How you stop something from stagnating aesthetically is trying constantly to reawaken yourself to what its source is. For me, this ties back to the idea of exploring the image as a tangible, physical 3D object, an idea which also comes across in your MUTE text, also titled "Human Resolution," in which you argue for the need to recognize "the exploitation and violence required for [digital technologies'] continued production". All your works seem to involve a specific move that isn't about exploring the face value of an image but instead the different ways it instantiates meaning and relations of various kinds. In contrast with the argument you make in the article, in which the image ties us to other people, the Human Resolution installation focuses attention back on the self. When people are looking at the projected image of themsleves in Human Resolution, are they looking in a mirror, or is there a better analogy by which to think about it?

HS: I think it's an abstraction of the self that reveals the way the "self" can be so quickly annihilated by representation.

HB: How should we respond to that?

HS: Well, I don't really think it's my place to say how people should respond to that. I merely thought that it was something worth putting out there. I respond to it by attempting to make work that expresses an increasing criticality toward what it is embroiled with, and by trying to be more politically engaged in my everyday life. There is an alternate way of thinking about things, and I found that resisting apathy and an "oh well technology's always exploitative so you should just get over it" mentality was a positive thing for me—for both my work and my well-being. It's more interesting to not get over it. That's why I can't answer the "what can we do" question because I find using technology to critique a problem more interesting than having a technological solution. I'd rather be engaged in a struggle for something than have any kind of solution where we can make a better internet or a better credit card or something.

HB: It's the same process of not critiquing the problem but improving it…

HS: Yep. A nicer capitalism.

HB: We should talk about Haptics, where artist Yuri Pattison invited you to make a touchable 3D hologram within his Faraday Cage project (a Faraday cage is a 19th century invention that blocks out external electric currents, which Pattison recreated as a residency space in SPACE Studios). What's the difference between this work and Human Resolution?

HS: Funnily enough, they're basically the same setup. I think that the Human Resolution show is a lot more interesting for me. Haptics was just a straight desire to reproduce this technology that I'd heard about, which was this touchable hologram, which I thought was potentially quite beautiful: that you could touch something that was a simulated object hanging in the space of a gallery that wasn't actually there. I found that more poetic and emotive and moving, in a more personal sense; something that would be touching, somehow. The promotional video for that technology contained one line that was "a floating image in mid air is no longer just a dream." There's this desire to give technology a physical form so there's at least there's something that will push back at you. I think I found that profound, in a way, because it means that people still desire each other, even if it's so mediated that they just desire to create some kind of holographic representation of something. It still speaks to a genuine desire for conjunctive social experience.

Human Resolution's a bit more negative, saying "look at you here as nothing but data". There's that Ashbery poem we were reading the other day where he says "much that is beautiful must be discarded so that we may resemble a taller impression of ourselves." There's a constant aspiration toward this image we've created of ourselves that we can't ever quite get to which is this, I suppose, want or desire: the "big other." You can't ever get it, you can't touch it. And data and Cloud computing perfectly fits into that as an ideological form because it's completely inaddressible.

The work is also counter-narrative in a way—it's not a finished work, it requires the presence of somebody to be there; it's not a film, it's not a sculpture, it's not a thing. Even if what it's exposing is quite a dehumanizing, digitizing process, it's still an artwork that's activated by the viewer's presence. The desire to make machines instantly responsive to the body plays on a strange sort of humanism, which is so close to digital property protection. We have these swipe screens and fingerprint scans under the remit of protecting oneself against identity theft, but it's also the protection of private property, which is inseparable from force in some sense.

In terms of the image used, in both, they're again playing on these ideas of touch and communication. I find it interesting because it references what you're doing with the object as you try and get the image to come out of it. You're kind of implicated in the image as well.

Flexible Display, 2013, CSM, London. Video installation: digital video, projector, water vapor, wood, plastic.

Age: 26

Location: London

How/when did you begin working creatively with technology? Started making websites when I was 15, because of getting an internet connection, and so taught myself HTML by copying and pasting stuff from other websites.

Where did you go to school? What did you study? Central St Martins—Fine Art.

What do you do for a living or what occupations have you held previously? I've worked in shops, a petrol station, the Tate Modern, and right now in a pub.

What does your desktop or workspace look like? I just work wherever I am / I don't have one. Right now I share one large desk with my flatmates and we have some plants which is great.