As Digital Preservation Fellow with Rhizome, my work has focused on archiving works of net art from the live web into the ArtBase. Net art, despite the benefits of being abstract - it rarely gets moldy! - is built on exceptionally fragile media. A server failure, domain shift, or missing file is enough to effectively destroy a work of art. As such, to properly preserve the pieces in the ArtBase, I work alongside Ben Fino-Radin to crawl, download, and adjust works for hosting in our archive. The scope of the ArtBase - from hypertext experiments to Twitter-fed visualizations - brings me in contact with an array of technologies, media, and unexpected use cases. While nearly every work of net art in the ArtBase founded on HTML, most go beyond it: embedded multimedia is very frequently used for a variety of purposes and effects. As such, developing a system to download and preserve complex media objects is of tremendous importance to my work.

One of the most common multimedia formats used in the ArtBase is Flash, dating back to its origins with FutureWave and through its development by Macromedia and Adobe. Of the myriad formats used in the ArtBase’s collection, SWF is the most prevalent and deeply used multimedia filetype: over a third of the archived works are founded on it. Its combination of power (few formats offer its combination of browser-driven multimedia and interactivity) and ubiquity on audience machines made it the obvious choice for artists looking to go beyond the HTML and JavaScript-driven net art of the late 1990s. Hence, working with Flash is greatly important to Rhizome’s preservation mission.

Splash screen, Inflat-O-Scape (2001)

SWF, as a format, presents a number of challenges for art conservators and archivists. As a binary format, it cannot be immediately parsed by text-friendly tools (such as web crawlers and text editors), and is thus machine- and human-unreadable. While SWF media resources are (blessedly) self-contained, Flash can link out of itself - and with no easy method to parse out URLs, these links are functionally invisible. Worse, the power of Flash allows for the creation of URLs on the fly: ActionScript can be used to generate an arbitrary string, which can then be passed to a resource call. Thus, even an exhaustive search for external links in a SWF object can miss potentially tens of thousands of necessary files.

While the outlook for conservation Flash-driven artwork looks bleak, all hope is not lost. A combination of specialized software, standard text tools, and careful analysis can preserve even the most complex Flash-driven net art. The primary tool for capturing and treatment of SWF-based art is the open-source swfmill, a self-described “xml2swf and swf2xml processor with import functionalities.” In other words, swfmill is able to take plaintext ShockWave File Markup Language (SWFML, an XML-based standard) documents and return compiled SWF objects - and, more importantly, do the opposite. By converting SWF into XML, we can parse the object as any other text file, via human reading or text manipulation tools.

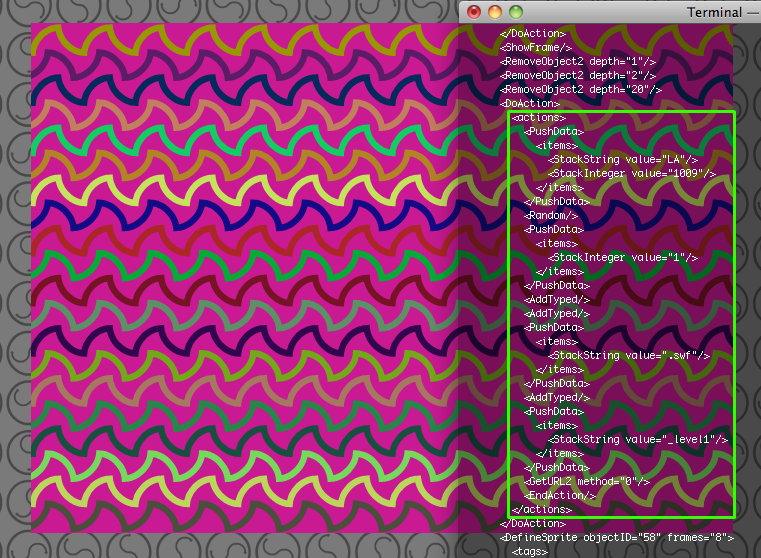

Typically, locating URLs is as simple as following a GetURL tag in swfmill’s output. On occasion, however, this is insufficient - more ambitious works may contain tags such as <GetURL2 method=”64”/>. While GetURL is used for direct resource calls, GetURL2 instead takes a path stored in memory; typically, from the output of a function. As such, trying to wget the listed resource is ineffective - few Flash objects have filename 64! Instead, a conservator must work backwards to try and understand the function’s possible results. This is best illustrated with a live example, from sign69:

Here, we can see that there are strings being stored with LA and .swf, the numbers 1 and 1009, some random number being generated, and a resource call being invoked. Piecing it all together, we can guess that this Flash file is simply a starting point for a random walk through a set of other files, named LA1.swf to LA1009.swf. By passing this series of files to wget (our web crawler of choice), we were successful in rebuilding the work in the ArtBase. This highlights the importance of human oversight in conservation: while automated crawlers that can parse SWF objects do exist, URLs generated as above are invisible to machines. Only by spending time with the work, and analyzing its structure, can more complex pieces be properly conserved.

As a non-destructive process, swf2xml does not alter the original file; as an open tool driven by an open standard, its provenance its clear. This is tremendously important for passing a file into swf2xml, editing it as a text document, and passing it back into xml2swf. This is necessary for preserving the functionality of works that span multiple domains; by adjusting cross-domain calls from http://www.rhizome.org/ to ../www.rhizome.org/, we can ensure that SWF links will not be broken when imported into the ArtBase. Given the open documentation of swfmill and SWFML, the process can be reproduced and followed by anyone wishing to audit our process. As such, future conservators will have no questions about how works in the ArtBase were preserved.

Looking forward, I suspect that conservation will increasingly resemble this model of careful application of specialized tools and understanding internal mechanics. Flash has the luxury of fifteen years of use and a near-universal install base; as such, there are existing tools and documentation for opening and examining files. As the ArtBase expands its preservation mission, the number of media formats encompassed will only increase - many of which will be undersupported, if not dead. Hence, Rhizome has been active in file identification and registration projects, taking part in hackathons and using its unique collection to advance documentation of media formats. By taking part in the greater digital preservation community, we hope to find new and clever ways to preserve past and future works of new media art.