The theme of Repair for this year’s Ars Electronica festival was apropos, as the festival moved to the Tabakfabrik, a former cigarette factory and sprawling complex of buildings that was churning out cartons of Marlboros as recently as last year. The smell of tobacco was still heavy in the air, and evidence of the factory’s work continued to linger: ear plugs still available in dispensers, pneumatic tube carriers still sitting in baskets, and boxes emblazoned with cigarette logos being used as exhibition design material. The factory, which is a protected historic landmark, is beautiful and perhaps deserved a Golden Nica of its own -- for best representation of the festival theme.

Although the factory has ceased production and is now, for better or for worse, at the disposal of the city of Linz after they paid 20m Euros for it, it represents the dire need for repair to our global economy. Demand for the factory’s former product continues, and one can safely assume the work has simply gone elsewhere, making the factory another victim of globalization. Though bank bailouts have faded from the headlines, the crunch is only just being felt in the art world as governments worldwide slash their already meagre culture budgets. Perhaps at this very moment in recent history, more empathy than ever before is felt between the pink-slipped worker on the assembly line in Linz and the gallery curator cutting yet another show from the exhibition schedule.

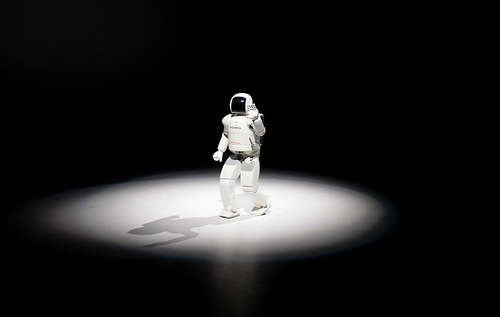

The grim warnings buried in the theme of Repair and the symbolism of a factory slayed by globalism and the bottom line aside, mostly Ars Electronica felt like business as usual. Despite a golden opportunity, the content of the festival rarely seriously engaged with the embedded message in the central festival venue. Combined with the self-contained nature and sprawling structure of the site, this meant it was possible to look beyond it as a corpse at the feet of capitalism and ultimately view it as more like a media arts Disneyland, complete with mascots that perform (Mickey, meet Asimo).

(Photo courtesy of Arts Electronica)

A key artwork in the Prix exhibition that made a real link for me between this remarkable and imposing venue and the festival theme was The Toaster Project by Thomas Thwaites. The artist attempted to build a toaster, not from scrap metal and microcontrollers, but from literally nothing, using raw materials and “a chimney pot, some hair-dryers, a leaf blower, and a methodology from the 15th century” to assist him. The result that was on show in the Tabakfabrik was a blob-like object in the vague shape of a toaster, along with other artifacts from throughout the process. The project’s poignant futility made it a subtle, clever, and appropriate project for this context, highlighting our reliance on worldwide industrial scale production. Though we may be subconsciously aware that we are, as individuals, incapable of producing something we can purchase for ten dollars at any department store, seeing the gorgeous and strange evidence of this is a demonstration of Thwaites’ grim wit and mad genius.

The winner of this year’s Golden Nica for Interactive Art was The Eyewriter, an inspirational project by a team consisting of members of the Free Art and Technology lab (FAT), Open Frameworks, and Graffiti Research Lab. Giving gravitas to the theme of Repair, The Eyewriter is a low cost tool inspired by graffiti artist TEMPT1, and consisting of custom software coupled with an eye-tracking system, enabling people with ALS to draw only using eye movements. The project demonstrates that collective working and DIY attitudes can produce inspired problem-solving and projects with massive, game-changing influence. As the project is a tool, it would naturally make a spectacular demo. The apparatus and documentation videos were professionally installed in museum style, but I found that this installation undercut the whole magic of the work. The piece cries out to be taken from its plinth, where it sits inert, and shown live to a crowd as a real-time demonstration. (Evan Roth, one of the artists, did some informal demos but there were none scheduled on the program).

Similarly, Stelarc’s Ear on Arm project, the Golden Nica winner for Hybrid Art, was installed more like a mini Stelarc retrospective accompanied by replicas of the ear on arm in question. A project over ten years in the making, Stelarc implanted an ear-shaped growth of cells under the skin of his arm, with the intention to eventually implant a microphone that will connect what the ear “hears” to the internet, and to also add a soft ear lobe. This work, like The Eyewriter, also begs for a live event, where people can see the ear-in-development on Stelarc’s arm, instead of documentation. These exhibition issues are not the fault of the artist, rather they represent an inability or unwillingness to be radical in the service of the work. While these works were among many shown in the exhibition as documentation, it seemed that as Golden Nica winners, they at least deserved something better than a staid exhibition-by-numbers approach.

The theme of Repair was broadly interpreted and materialized throughout the festival in the shape of everything from the Golden Nica winners to a free massage service, but one other area of the festival stood out in terms of an elegant elucidation of the theme. Stop Recycling, Start Repairing by Dutch design collective Platform21 was a playful and genuinely interactive part of the festival. Through a myriad of displays, festival-goers could learn how to use felting to repair holes in sweaters with colorful contrasting fibres, use Lego bricks to fix crumbling bits of buildings, or repair broken dishes with gold leaf based on a 15th Century Japanese technique, to name three engaging examples. The group also produced a “Repair Manifesto” which succinctly and clearly outlined their philosophy, from “to repair is to discover” to “even fakes become originals when you repair them”.

(Part of "Stop Recycling, Start Repairing") (Image courtesy of Ars Electronica)

(Part of "Stop Recycling, Start Repairing") (Image courtesy of Ars Electronica)

In the midst of it all, I found myself again and again gravitating towards the beating heart of the whole festival experience, “TELE-INTERNET” curated by Aram Bartholl. The salon-like space had a few terminals set up, internet-cafe style; some folding chairs around a small stage area; and several long tables covered with stuff and people working side by side to make things. Informal talks were held in the small stage area, and you could grab a coffee or the German hacker’s drink of choice, Club-Mate, while listening in. There was a sense of things both happening and about to happen, an unmistakable buzz. Festival goers could sit down and make something, listen to someone talking about things they were making or doing, or just drink coffee and use the internet at one of the terminals. It was a bit of blissful semi-chaos that encouraged people to stay and so was often very busy. Bartholl always played the arms-length host, letting things unfold, giving me the sense that if I wanted to, I could have grabbed the microphone and just started talking. It was a situation that I wished could have gone on for days or even weeks, to see what would happen and eventually evolve.

As part of the conference programme, Richard Sennett, author of The Craftsman, gave an interesting talk that raised the valuable point of how collaboration collapses when our tools smooth the process too much. He used the example of failed experiment Google Wave to illustrate how our online tools sometimes conspire to make the process look easier than it is. In his talk, and in discussing this particular example, perhaps Sennett nailed the question of the festival’s theme on its head, which I’ll paraphrase as: why deny the fact of complexity in collaboration? For a system to repair itself, we need to work together, and a true and complex collaboration is definitely beyond the scope of a single festival.

Michelle Kasprzak is a writer and curator based in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. She is currently Project Director at McLuhan in Europe 2011, a cultural network project that will celebrate the legacy of Marshall McLuhan as a media and telecommunications visionary across Europe in 2011, the 100th anniversary of his birth. More about Michelle: http://michelle.kasprzak.ca