Humor, fun and nonsense often figure greatly in the current modes of communication on the web, whereby memes and sardonic blog comments are commonplace -- if not expected. Such trappings have found their way into media art practices from Cory Arcangel’s cover of Arnold Schoenberg’s op.11 Drie Klavierstucke using cat videos on YouTube to F.A.T. Lab’s Kanye West Interrupt bookmarklet. The question that these works and others like it raises is this: does humor appear to be a synergistic outgrowth of technology (and how does it relate to its development)?

In the latest exhibition "Fun with Software" at Bristol’s Arnolfini, curator Olga Goriunova seeks to document and explore how humorous approaches to software lead to innovation. Working with early net and media artists from JODI to Graham Harwood, the exhibition is a retrospective of peculiar approaches to computation. I sat down with Goriunova to talk about the show’s premise and how that premise contextualizes and contrasts the current era of humor and technology.

A great deal of media art has gone the way of social media, mining memes for cultural critique. Why do you think humor seems so endemic to technology and community? Does this at all translate to computation and software cultures?

The concept of meme is an interesting one. On the one hand, it doesn't exist, but on the other hand, the concept fills some void in the drive to understand and explain how network culture works, and is being widely, and successfully, used. In my opinion, a meme is about repetition, imitation. If we are to use a Nietzschean eternal return and the interpretation of it in Deleuze's Difference and Repetition, there are three kinds of return: a repetition of habit (almost physical), a repetition of memory and a third (ontological repetition) that undoes the previous two. The third repetition is about passing an “exam” of becoming: only the excessive, powerful, or different can indeed return, become. The third repetition is a “pure act of difference”. Here, meme concerns the first two kinds of repetition, whereas the “fun” that interests me, is about the third one, the eternal return.

This is not to say that the first two are uninteresting, and meme seems to be able to reveal something about the ways in which digital culture operates, the stages creative production might be going through, the aesthetics about to become.

What I am interested in with this exhibition is to show, to put it crudely, that freaks run the world. It is about people inventing codes, usages, concepts, computer functions and a variety of things that change the world through a joke, through absurd acts, through unnecessary and un-pragmatic thriving for a difference.

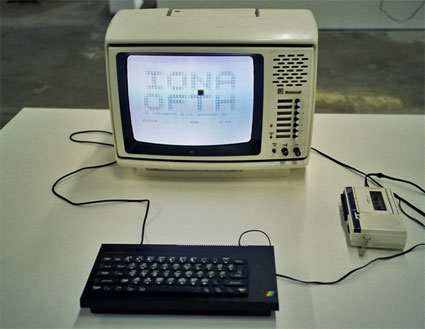

(Installation at "Fun with Software")

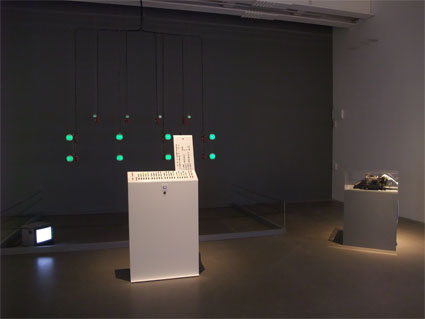

(Installation at "Fun with Software")

There is a lot of artist work in the show, but also a number of projects that are done as a ‘geeky’ thing in a context radically different to art, such as Erik Thiele's Tempest for Eliza, for instance. It is a project done by a programmer “for fun” and the author was never interested in presenting it in the art scene. The project comments on TEMPEST - a secret service term coined in the 1970s to refer to the usage and the defense against the so-called ‘compromising emissions’. Such emissions are electromagnetic waves that are emitted by every electronic device, including, for instance, a computer monitor, and which could be intercepted in order for the data displayed on the monitor to be reconstructed. Thiele makes his monitor display black and white stripes of different width, which ‘play’ For Eliza and other musical compositions on the radio that catches the radio waves emitted. It is an artistically brilliant piece of work. Being a statement within a particular programmer's culture, almost folklore, it has the precision of the greatest work of art without any pretense.

Such moments of pure difference, where fun is the absurd, the non-pragmatic, experimental act that produces a change and gives birth to a new way of making things which the academy, industry, art and design practices, cultures then follow drive the pathos of this show.

You’ve previously relayed that there was a conscious decision to focus on the "non-industrial, non-professional, non-commercial, or non-academic character" in exploring computation and software cultures. Can you explain why you’ve chosen to focus on “fun”?

I've partly talked about what I mean by “fun” above. It may not be the best term to describe that free exploratory drive that is linked to pleasure, humor, and randomness, but there also seems to be no better one. For me, humor is not so much about affect. Humor and fun link to the registers of becoming of something new and thrilling. Such newness can and often is used as an innovation later on, but its ways of engendering are of a different order to what business interests try to stage now through “encouraging creativity and innovation.”

Such humor, and laughing, are more akin to a Nietzschean “nobleness of being capable of follies,” discussed in The Gay Science. It is in his “the gods are dead but they died from laughing” that an answer to such laughter lies. It is a laughter that changes the ontological status of reality with audacity, folly and nobleness.

Such fun is not a banal giggling, but an inquiry into the unknown, which takes its path through the unserious, which means a lack of grandeur. The pathos of such inquiry is not the one of the feat of Captain Gastello, or Mendeleev's day and night amplification of thinking that made him dream the periodic table, but one of a small try, however laborious and precise it can be. The act of such humor is serene and sincere, and exact, but of a modality different to the one we're used to in the rhetoric of either invention or progress. A breakthrough achieved through such laughter is not loud, but its profoundness can't be underestimated.

Can you explain how this peculiar approach is illustrated in some of the works in the show?

A lot of projects in the show use equipment for purposes not intended by the manufacturers and invent ways in which both software and hardware can exhibit various versions of their materiality by blowing up the habitual and the dominant ones. Here, we have a reference to the digital folklore of the 1990s - with WIMP by Alexei Shulgin and Victor Laskin, and the two classics of software art: Auto-Illustrator by Adrian Wardand I/O/D/ 4: The Web Stalker by I/O/D.

WIMP gathers its inspiration from small virus-like prank programs of the 1990s, which would flip the desktop upside down, shake icons, change interface colors, let all desktop folders drop down and fill the screen with dozens of pop-up windows. Such jokes were necessary at times when Windows “blue screen of death” (error screen displayed upon encountering a problem that makes the operating system “crash”) was a relatively normal state of a computer. It is also a VJ tool that uses elements of Windows graphical user interface (GUI) as its sole source of visual material. WIMP does not only accompany sound; it critically comments on the aesthetic dominance of the visual elements which became the core of GUI, in fact, for rather random reasons.

The “inappropriate uses of software” strand is continued by a well-known deconstruction of a race game R/C STORY by Retroyou. It is done by only changing the pieces of code made available to gamers by the manufacturers, which explodes the game, making it into a non-functioning, abstract and absurd 3-D environment in which one can attempt some action but would most [likely] end up flying into open sky.

There is, then, a lot to be said in a “hacker” ethos in many of the works. You cite how the 1980s brought about the "'hackerization' of youth" culture; can you explain this notion, and why it’s so important for the context of the show?

There is, of course, a heated debate trying to establish the pristine meanings of the terms geek and hacker. For Christopher Kelty, geeks form a “recursive public” that comes into being through a shared practice of taking care of the technical means that bring the public together. There are imagination, a moral responsibility, and technical structures that are central to such understanding of a geek. I won't even go into the accounts of a hacker.

What I meant by “hackerization of youth” in the 80s is much more small-scale, unformed and naive. Kelty specifically talks about “geeks” as being those that are “not the ones that play with technology of any sort”, not “script kiddies.” My geeks, or hackers, are maybe indeed script kiddies, are more of Guattarian “machinic junkies.”

These are the people that were the first generation of teenagers to spend their life in front of the first home computers of late 1970s and 1980s, which, to borrow the words of the founder of Micromusic, an 8-bit music community, had to “defend themselves for spending time with computers”. Carl says, “A lot of people laughed at you and thought you were weird. I can remember fighting with my father about the television set. He wanted to watch the news but I needed it as a monitor so that I could write my programs in Basic.” DRX (from Micromusic) [relays], “That was maybe the first generation, sitting in front of the TV screens in attempting to create musical tracks 'that would have been as cool as in Arkanoid'.” (Quotations from Baumgartel, Net.Art 2.0).

Early demo and tracker communities are not represented in the show, but JODI are re-doing their Jet Set Willy Variations on Sinclair ZX Spectrum, JET SET WILLY the making of, for the exhibition version in Eindhoven. The Bristol version of the show includes their film All Wrongs Reversed © 1982. It is a recording of JODI programming Sinclair ZX Spectrum to produce graphics. The performance is captured off the TV screen. You first see ZX Spectrum being loaded from tape; then, a program runs, producing very formalist, distinctively JODI-ist graphics which is altered in real-time by changing variables in code that is displayed along, through and with the graphics. It is rather straightforward if you can follow Sinclair Basic (and even if you can't), but not at all “simple”. JODI go along the boundary of what was offered as a platform for home entertainment in the 1980s (for which entertainment purposes was the command “flash” included in Sinclair Basic?), and deconstruct, remind, reveal, and create the language that is used up to day.

Do you think we are working towards a generation of coders?

No, we are working away from it; from a certain understanding of it, at least. In a way, this show is about things that are over. Net art and software art aesthetics is now being re-used in applications running on iPhone[s], and 90\% of what populates such spaces utilizes digital aesthetics developed in the 1990s.

We have two works that engage predominantly with the contemporary developments: the wowPod sculpture by Electroboutique and Satromiser by Jon Satrom and Ben Syverson. Satromiser is an application that will be presented on iPad, and it reflects on the role that software art played in destabilizing the ‘boredom’ of software to the degree, by which contemporary software aesthetics is updated to include various kinds of “anti-boredom” - made entertainment - into its core. wowPod is a gigantic distorted iPhone that is fully functioning and is able to display its normal content in a manner stylistically aligned with its physical shape. The “idiotic” fleur of this project is a very important aspect of fun, which is not afraid of the falsehood and of primitiveness as a mode of exploration.

"Fun with Software" is on display at Arnolfini in Bristol, UK, through November 21st. It will travel as "Funware" to MU and Baltan Laboratories in Eindhoven, NL, from November 12th - January 16, 2011. Lastly, it will travel to Hartware MedienKunstVerein in Dortmund, DE, in 2011.

The Eindhoven show will conclude with a one-day conference during STRP, a premiere art and technology festival, on November 27th. The list of speakers includes: Wendy Chun, Andrew Goffey, Matthew Fuller, Wilfried Hou Je Bek, Adrian Mackenzie, Simon Yuill and Michael Murtaugh. In addition to the conference, Goriunova plans to document and author a book related to the subject.

Lisa Baldini is an international curator, writer and new media practitioner based in New York, specializing in media, sound and process-based art. Presently, she is an adviser to GOLDEN Gallery in Chicago. Her independent projects have included exploring the critical relations between aural/oral cultures and technology through the likes of open source media and performance. In addition, she is the founding curator of the open source curatorial series Power and a founding member of the MAIM Collective.

What a huge and fantastic interview and it reminded me this work, not refering software but technology http://www.youtube.com/oceanoperdido#p/u/15/YiG49OPq0qY and also some kind of humor. It was one of the works selected at a contest called Vida (which is now on the 13th edition), and it is focused on the interactions between life and artificial life. Congratulations for this excellent article!