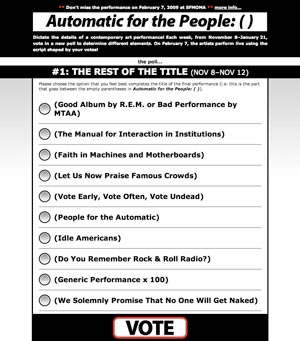

In the fall of 2008, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art invited several artists to create a new work for the exhibition "Art of Participation: 1950 to Now." One such invitation was extended to MTAA, a Brooklyn-based duo comprised of Mike Sarff and Tim Whidden, alternately known as M.River & T.Whid Art Associates. In response, MTAA constructed a poll-based project entitled Automatic for the People ( ), which asked the audience to vote upon the parameters for a theatrical performance executed at the conclusion of the exhibition (the title’s empty parentheses refer to an undetermined subtitle). Technically, the voting consisted of ten different electronic ballots addressing such creative and procedural elements as duration, space, and props, with each being accessible for one week at a museum kiosk and remotely online. All ten ballots contained ten options, and the most popular selections were incorporated into the live finale. During the summer of 2009, I enlisted MTAA in an email-based interview regarding the practical consequences and conceptual implications associated with producing their participatory poll and performance for SFMOMA.

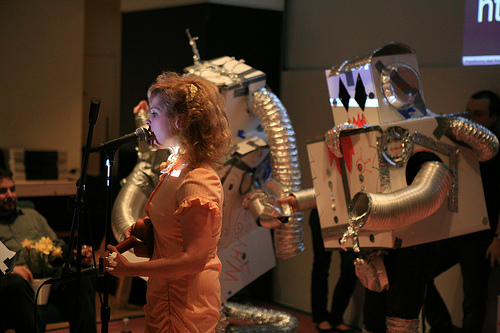

(Photo: Aimee Friberg; Courtesy of SFMOMA. )

DAVID DUNCAN: Let’s begin with the project’s finale. Can you give an overview of the performance— the staging, players and performers, costumes, and actions?

MIKE SARFF and TIM WHIDDEN: We began with the idea that the live work should come together as a unified whole; we felt that a series of unconnected actions would feel untrue to the vote process. We also wanted the audience to participate in the performance. To achieve this, we established three boundaries— installation, duration and action. For the installation we had a location outside the museum’s freight elevator that was selected by vote. The performance’s duration (the same length as the REM album Automatic for the People) was also selected by vote. The action involved two teams competing to create the best robot costume—again, an element determined by vote. Lastly, we included interruptions to the robot costume building competition. These we called interludes and digressions—they were essentially acts between acts that helped to pace the performance. The goal was to make it all seem solid even if an audience member did not know anything about the whole of the AFTP: ( ) voting process.

DAVID DUNCAN: Beyond the audience’s participation, did MTAA conceive AFTP: ( ) in cooperation with the SFMOMA staff?

MIKE SARFF: Yes, it was conceived for this space and institution. It would be good to note here that although the vote kiosk installation and the two performances occurred in the museum, the work was also operated in the public space of the net.

DAVID DUNCAN: Do you feel AFTP: ( ) offers any implicit or explicit quality of institutional critique?

MIKE SARFF: Tim and I disagree a bit on this. For me, the push-and-pull of museum context is background noise, and the heart of the work is the conversation between people. How can we speak and build together? What do we all want? For Tim, the manipulation of the context of “artist”, “viewer”, “performance” and “museum” is fundamental to the work. He sees the conflict between what people expect and what we do as the point the project opens up.

DAVID DUNCAN: When noting that AFTP: ( ) operated within the public space of the internet, Mike seems to signal that the project was executed in a more open or neutral format. Do you mean that, to the extent that a project produced in collaboration with SFMOMA is sited online, it is relieved of institutional associations or implications?

MIKE SARFF: Not really, but I feel it is important to note that the people who came to the work via the net may have a different relation to the context of the work than those who entered from the physical space. The net has it's own protocols. It has its own associations and implications. The project, along with other projects in the show, overlaps some borders but they do not replace the borders, just soften them. I guess this is what might interest me in the institutional critique line of questioning: When you soften the line both contexts are modified—both the museum out to the net as well as the net into the museum.

TIM WHIDDEN: I wouldn't say that either. For me, it required the institutional associations to a certain degree. It was produced and decisions were made with the institution in mind.

DAVID DUNCAN: Within an SFMOMA online interview Mike notes that you built a system that allows the audience to vote for the wrong thing: “They will vote for the thing that we should probably not be doing in a museum. And that's the humor of it to me. . . .” Mike’s quote recalls John Cage and how artists navigate or employ indeterminacy. It also suggests that—in relation to issues of institutional critique— determination, or what should or should not happen, is directly linked to the museum space, and what an audience expects to find there. Do you think determination stands in direct relation to the museum environment, if determination exists at all?

MIKE SARFF: It might be good to start by questioning the idea of the museum context as a solid structure. For me, it helps to view the context as a bit more malleable and organic in its nature. I do understand as an artist, and the viewer understands as a viewer, that an art context exists around the work. Both the viewer and artist make choices with an awareness of that context. But again, that awareness is not what interests me.

TIM WHIDDEN: A physical and bureaucratic institution like an art museum isn't comfortable bringing anything within itself that can interact with its systems in ways that aren't predefined and predictable. I don't see anything wrong with that.

DAVID DUNCAN: Did MTAA have the ability to recognize wrong votes?

TIM WHIDDEN: I think Mike meant "wrong" as meaning that the vote would give MTAA an uncomfortable task or go against institutional convention. We assumed, and the voting patterns seemed to suggest, that most people's intention was to pick the most absurd choice or the choice that they felt would be the most interesting to see us try to interpret in the museum. This is excepting where people gamed the vote; a few polls were decided by one dedicated voter for their own reasons. But I also felt a choice was "wrong" if it was too conventional. Like "general public" being chosen as the audience. Too conventional! Why would anyone vote for that?

MIKE SARFF: Yes, "right" and "wrong" may not be the best way to state it. I understand and enjoy that play is a part of this dialogue. People may have voted for the difficult or strange answers for us to produce. I would guess one might do this because it is more interesting than picking an easy answer. It's not that difficult or strange answers are wrong choices. They just break with the logic of the way we vote for things in a political context. Can I tell if it was a "wrong" choice without checking on intention? Not really. In a vote where an easy answer came up, like "general public" for audience, I can imagine that people may vote for what they think is correct. When odd answers like "robot" for wardrobe comes up, the choice seems to be a playful. But again, even with the comments left on the website and some conversations with people who voted, it's hard to gauge motivation. The only path we could take was to approach the choices as equal and true for the work.

DAVID DUNCAN: Did anything seem right or wrong when you recently executed your performance?

TIM WHIDDEN: As we executed the performance? No, no choice by the audience seemed right or wrong. But we had been living with the choices for a while and had structured the entire performance around those choices so it just sort of seemed to be the way it had to be. Of course, whenever an artist does anything and sends it into the world there are parts they like and other parts, well... not so much. Though we followed the polling to create the piece, in the end, it was still MTAA creating the piece. We lost no authorship.

MIKE SARFF: In conversations with the museum and with some friends who took part in the voting, we would get asked, "What if 'A' or 'B' is picked? What are you going to do?" I think our concerns revolved more around linking the individual votes into a cohesive whole without the work becoming a set of pasted together choices. I don't want to lessen the weight of people's choices. I do think when a person votes on duration, subject matter, costumes, and so on, they spin the work in different directions. But as Tim said, in the end it was our responsibility to take the desires of the voters and mold them into a whole that can be presented in the final performance. Again, this system of information exchange drove the work for me. I wanted to see what people wanted. Wrong vote or right, as long as they decide, the project works. They only real wrong choice, for me, would be if someone looked at the work and walked away. But thankfully, people where engaged enough with the system that they took part. And I hope that the performance was true to their input.

(Photo: Aimee Friberg; Courtesy of SFMOMA.)

DAVID DUNCAN: I would like to return to a slight difference in your individual perspectives. Where Mike clarifies the museum context as “background noise” to an art project that facilitates a “conversation between people,” Tim sees “the manipulation of the context of ‘artist’, ‘viewer’, ‘performance’ and ‘museum’ [as] fundamental to the work.” Together, your viewpoints remind me of [exhibition curator] Rudolf Frieling’s thoughts on participation and contemporary art. In particular, I believe your statements recall his idea that “the concept of a museum as a container of finished artworks is not contemporary anymore. Its contemporary when it opens up to production, and to being a site of production.” I cite this quote, because one of you proposes the facilitation of conversations as opposed to the execution of finished artworks, and the other proposes a tweaking of the viewer’s traditional museum experience. It would seem that you both envision a project that is contrary to the notion of the museum as a container. Is Frieling’s conclusion accurate to you? Is this a concept that you find agreeable?

MIKE SARFF: Yes. Art can function as a verb. Rudolf follows this thought by reimagining the museum as a site of production. Within this site, active work can be seen and understood through a time frame, not just an endpoint. For AFTP: ( ), this shift is important—the communication of the voting process is given the weight it needs in relation to the final performance. If that weight is taken away, then the final performance becomes a skit or play. With the dialogue of the vote, the work exist as intended—as an active social artwork.

TIM WHIDDEN: Let's hope that museums catch up to Frieling's vision. But I don't see Mike's view and mine as either/or. One doesn't cancel out the other. The simple fact that we can have the conversation is a tweak to the museum. Mike doesn't care about this; to him it's just a fact of how things now work . . . it's the museum being "contemporary," as Frieling says. To me, it's not a given. It's still an area that can be explored. But yes, the piece definitely doesn't take the notion of the "museum as container" as fact.

DAVID DUNCAN is an artist and art historian based in Brooklyn, NY. In 2009, he co-curated Films by Robert Morris at Hunter College in New York, and a forthcoming catalogue will feature essays by Chrissie Iles and himself. During the spring of 2011, the Morris Films exhibition travels to the Institut Valencià d'Art Modern, Valencia, Spain; Museum Moderner Kunst, Vienna, Austria; and the Musée d'Art de Toulon, Toulon, France. Duncan is also a regular contributor to Art in America magazine.