Renowned light artist James Turrell (1943, Los Angeles) was first associated with the American Minimalists that emerged in the 1960s such as Donald Judd, Robert Morris, and Frank Stella. Today Turrell is known more as an installation artist who uses colored lights to sculpt space and disorient perception. Currently Turrell lives in Flagstaff, Arizona, near the Navaho reservations, where he continues to oversee the completion of his monumental land art project at Roden Crater, an extinct volcano that the artist has “been transforming into a sky observatory for over three decades." In honor of the recently opened James Turrell Museum in Colomé, Argentina, the only museum worldwide dedicated specifically to the artist's career, this article discusses highlights from Turrell’s rich body of work and introduces the new Turrell Museum, where many of these pieces reside.

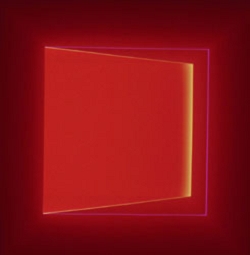

Turrell’s artworks undermine expectations and assumptions about so-called objective reality. For many critics and scientists, colored light exists in thick mists and objects in the world, external to the perceiving eye. For others, such as psychologists and some artists, it is quite the opposite: through a series of internal retinal processes, one sees something called “color.” In this view, light and color seem to be in the world, but in truth, they only signify their absence. Light is a logical negation. This paradox is consistently explored throughout Turrell’s work, from the earliest pieces made in the 1960s, through his current projects still underway.

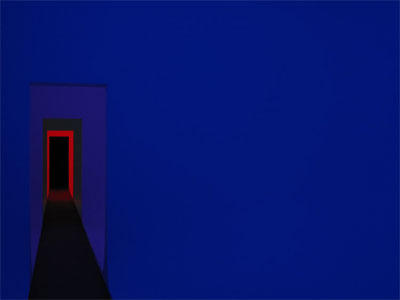

The very early Ganzfeld Series (1967) used light to create the appearance of geometric space. In one, Turrell projected bright white light across a room. The crisp borders created in these light constellations, on top of the difficulty of seeing any textures on the surfaces that were lit by the light, made it seem as if a section of the wall had been taken away, and light had entered from the outside. This motif was repeated with Ronin in 1968 where a fluorescent bulb was placed at the intersection of two perpendicular walls. The effect it created was the illusion of a veil spread across the space between the partition and the wall.

Wedgeworks (1969) was another piece that formed a “real” illusion with sculpted light. In Juke Green (1968) and the Space Division Pieces (1976), this technique was pushed even further. Viewers were often convinced that the objects really existed in the corners of the room. In fact, in the 1980s, during one of Turrell’s exhibitions at the Whitney Museum, a woman thought she was leaning against a wall, but it was really only the effects of the light that created the illusion of a solid space.The lady ended up falling and breaking her wrist, after which she sued Turrell.

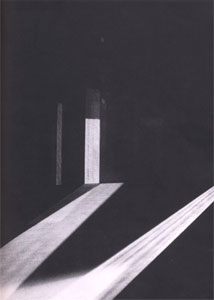

The paradox of light does not only exist in the “outside” world. Turrell’s infamous Mendota Stoppages series (1969-1974) demonstrate that the paradox of vision also occurs in the absence of external stimuli. Mendota Stoppages made use of available light sources outside an unused hotel in the bohemian neighborhood of Ocean Park, California. From 1966-1968 Turrell spent his time sealing the room on the ground floors and making the interior walls perfectly smooth. Between 1969 and 1970, he held performances in the evenings. He directed the movement of the diagonal lines of light across the room. These performances were conducted in nine stages and by the end, viewers’ eyes had grown weary in the low light conditions. Near the end of one performance, Turrell shut all the light apertures and reduced the room to black. However, many audience members continued to see light. They believed that the lighting had remained at this low level, but they were mostly likely experiencing retinal after effects that were internally produced.

Turrell remains committed to exploring the uncertain edges of light phenomenon. However, this fidelity has not gone without a personal price tag. On top of the lawsuit noted above, in another situation, a pirated clip from one of his works was inserted into a Pokemon cartoon. This unexpected insert set off “a rash of seizures and nausea that sent more than 700 people to the hospital in Japan in 1999.” Turrell explains that, “The clip had been compacted, removing the spaces that had been inserted precisely to prevent the possibility of inducing photosensitive epilepsy.” This, as he puts it, was a “War of the Worlds kind of broadcast.”

These strange and unfortunate cases do not reflect the aesthetic principles in Turrell’s work. However, they do point out that the installations hold many lessons in perception and light that we can still learn from. The artwork, as Turrell has described it, is akin to the “deer caught in the head lights.” It is this glazed-eye state, Sean Cubitt explains in “Immersed in Time,” that effectively characterizes the aesthetic experience of the work. Almost all of Turrell’s works ask us to see color and light as a medium, not through which we may understand, and know the world, but, like a deer caught in headlights, stare in disoriented confusion, and begin to ask new questions.

Turrell has had over 160 solo exhibitions worldwide since 1967. In addition to 22 permanent installations at institutions such as the Henry Art Gallery, Seattle; The Nasher Sculpture Center, Dallas, which opened in October 2003; and P.S. 1, Long Island City, New York, James Turrell’s work can been seen in over 70 international collections including: the Hirschhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington D.C.; Mattress Factory, Pittsburgh; Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt am Main, Germany; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Panza Collection, Varese, Italy; Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, Arizona; Sprengel Museum, Hanover, Germany; and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

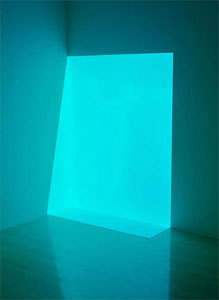

The new Turrell Museum, which celebrated its opening on April 22, 2009, is part of the Hess Art Collection, commissioned by Swiss businessman, wine producer, and art collector Donald M. Hess who built the museum to showcase nine light installations representing five decades of Turrell's career. Also for the museum, Hess commissioned two new installations: Spread (2003), a walk-in environment consisting of blue light, and Unseen Blue (2002), the “world's largest Skyspace.” Additional pieces in the collection include Alta Green (1968), and Lunette (2005), which involve a corridor whose “interior has been punctuated by a vertical portal to the outside sky and filled with natural and warm white neon light,” and the site-specific Stufe (White) (1967), City of Arhirit (1976), Slant Range (1989) and Penumbra (1992). The museum site is also based on a plan created by Turrell. Visitors will have to make the trip to decide where the truth of light resides.

The truth of light… and the paradox of light.

James Turrell's work is really strange to experience.

Threre is really nothing except for light. Everytime you experience the work it makes you rethink what light is..

I like work that messes with perception that makes you really feel the limitation of being human.