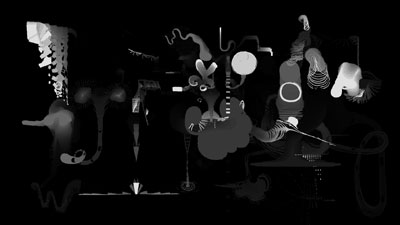

Image: Takeshi Murata, Homestead Grays, 2008, (Still).

"PREDRIVE: After Technology" (currently on exhibition at The Mattress Factory, Pittsburgh, PA November 14-April 2, 2009) features new works by six international artists including Takeshi Murata, Paper Rad, Gretchen Skogerson, Antoine Catala, and Brody Condon. The exhibition was conceived with a very specific group of artists in mind -- artists who placed both the dysfunction and arrogance of ever-changing technologies at the center of their work. In a sense, these artists are working in the shadow of a technological dystopia (and euphoria) that had begun as early as the Industrial Revolution -- as expressed in the vacant, vectored glances mapped out in Edouard Manet's The Balcony (1868-69) or the absolute pleasure of stop-motion animation in Georges Melies' An Up-To-Date Conjuror (1899).

Below, I speak with two of the featured artists in the show, Takeshi Murata and Jacob Ciocci (of Paper Rad) -- we cover everything from readymade software aesthetics to the dream of the perfect collector -- someone willing to take the risk of simply buying an idea. -- Melissa Ragona

Melissa Ragona: Last night I was asking about how you each manipulate your work at the level of the pixel. But, in a larger sense, I want to know where your work is going in terms of its relationship to technology -- especially because "PREDRIVE" is about what I am calling, the anti-wow effect of new technologies -- the disappointment of new technologies' promise to bring us somewhere else faster or to offer a yet-to-be imagined visual/audio space. I first became interested in so-called "new media," through structuralist film, focusing on filmmakers like Hollis Frampton, Paul Sharits, Tony Conrad, Joyce Wieland, Michael Snow, Peter Kubelka, et al. And then began exploring, a second generation of filmmakers who were also interested in film as epistemology (studied at the levels of the frame, or projection systems, or editing) primarily through the Six Pack group in Vienna which included filmmakers like Martin Arnold, Brigitta Burger-Utzer, Alexander Horwath, Lisl Ponger and Peter Tscherkassky. And, then most recently, artists involved in information visualization projects like Martin Wattenberg, Lisa Jevbratt, Ben Fry or Golan Levin. So, while I am still interested in work that is rigorously formal and reflexive about the use of technology - I am less impressed by what it produces visually. So, I know that in your [addressing Takeshi] most recent work you seem to be experimenting with freer, more improvisational forms. Or it seems that the focus is more on the relationship between frames rather than at the level of the pixel [as in Monster Movie or Escape Spirit VideoSlime].

Takeshi Murata: Yeah, but for me it has more to do with working within a different historical context. In the work I was doing earlier [as in Monster Movie] -- it's a great open territory -- working with new tools like computers or software programs. The technology is moving so quickly that there's much less of a framework through which to see the work. Now that I am working with more traditional forms of animation again, I have its history to work from, for better or worse.

Jacob Ciocci: So I have a question for Takeshi -- so what's an example of this newer form you were referring to, you mean like rethinking animation? And which older pieces of yours are we talking about?

TM: Well, like Monster Movie. And I'm thinking mostly about the level of incorporation of the computer, or where it’s incorporated. I initially was drawn to using the computer because of the speed. When I started to work with hand-drawn animation again, one of the main issues that was really important to me was the length of time it took to make work. If you can make something really quickly, it can change everything. I learned by doing traditional animation -- you know, you would write out script, storyboard, keyframing, you know all the classic stuff. But, in the end, like 90% of it is simply pounding it out.

Image: Takeshi Murata, Escape Spirit VideoSlime, 2007 (Still)

JC: Yeah, right. Just sitting there and pounding it out.

TM: Yeah, because there isn't room for any kind of experimentation or growth -- what you can do is simply limited at that point. One of the reasons I got into computer-based work is that it allows you to put that process in another place; you could make things happen in different directions.

JC: Okay, so you got into computers in that way. Now, it's an example of something that is moving back toward this other model of animation. Give me some examples of that newer work.

TM: Well, the latest hand-drawn animations.

JC: Like what?

TM: Well the video I just finished for the Mattress Factory is Homestead Grays. I haven't really found an exact balance yet -- like the thing I did with Billy [Dearraindrop] in London was straight animation, but we stripped it down to only white forms on black. We were using the computer to be really fast and that was a huge step up.

JC: So when you started you weren't using computers at all, right?

TM: No, right it was all film.

JC: Wow, that's amazing.

TM: Yeah, the process gave me so much respect for artists who were making animation before computers.

-->-->

JC: So, are you now really using Wacom tablets? Do you have a Wacom tablet? [laughter]

TM: Yeah

JC: So, all my students are using them -- it's like this little tablet where you draw on it with a pen and it goes straight to the screen. I have these students who say, "oh I want to draw," and then they suffer because they can't really scan well or take good photographs of the drawings. It's so fun to draw with the light table, but then it is so hard to make it look good. Whereas the Wacom tablet kids are just burning through their stuff.

TM: You don't use one though, huh?

JC: I have never used one, no. All my drawing is just with a mouse.

TM: Wow. Yeah, like I had a friend who did that - it's its own crazy thing. I can't do that at all. [laughter]

JC: Yeah, well the reason is because when I started doing Flash animation it was -- well I guess I could have had one, but I didn't really have any money to buy one. I guess the way I learned to create forms was by making simple lines and then changing the curve of the line with a mouse. I think that has been a big part of the Paper Rad aesthetic, for sure. Ben [Ben Jones, another member of Paper Rad] was even doing this with the pilot for a TV program -- drawing exactly what the frame should like and then scanning it in and tracing it with Flash. But my sister Jessica (Jessica Ciocci, another member of Paper Rad), I think, was doing the tracing. I think she was just using a mouse. Which is crazy, but again just going back to the idea of a Paper Rad aesthetic - I think it was this idea of a limited palette of options. Just going with whatever the presets are, whatever comes out of the package first. As opposed to making or developing your own really distinctive aesthetic within a software. But consequently, because we did that, a really interesting thing happened - all of a sudden it started to look really distinct. So, now people are like: "oh, that's the Paper Rad look" - the use of color with Flash and a particular style of editing. We didn't conceptually decide: "Oh, this work is about prepackaged technology!" It was like a direct, emotional reaction to technology: This is my experience of getting a computer, opening it up, this is how I want to use it - fucking around with it like a little kid. You have to edit that out! [laughter]

Paper Rad, Problem Solvers, 2008 (Still)

Paper Rad, Problem Solvers, 2008 (Still)

MR: Well, like when I saw Ben's [Jones] Facemaker in Takeshi's curated show, Heavy Light, it felt very dated - [Heavy Light premiered at Deitch Projects in New York in August 08, then was screened at Pittsburgh Filmmakers on November 8 in conjunction with the exhibition, PREDRIVE at The Mattress Factory]

JC: It is old!

MR: Yeah, but in a very cool way -- it's using technology from that period, so the look is still distinctive, even though other younger artists have ripped it off, there is still a Paper Rad stamp on it.

JC: Yeah, I think that's it honestly -- I don't think that has that much to do with the technology and more to do with the fact that whenever Ben does something he's not just thinking about style, he's also thinking about it on so many other levels. Because I don't think so much has changed since the technology of Flash, it is not all that different from where it started. For example, he made Facemaker like in 2005. It's just that the world around us has changed so much aesthetically. Like everyone does that fake 8-bit pixel aesthetic now.

Image: Paper Rad, Facemaker, 2005

Image: Paper Rad, Facemaker, 2005

TM: Yeah, so Flash, since it wasn't pixel-based anyway -

JC: Yeah, so it was a really backwards idea in the first place, because what you have to do is to make something look pixel-like in Flash, you have to - it's really a pain, because Flash wants to make everything look super smooth and like clean or curved edges. So to make it look pixel-like in Flash, you have to do all these weird - well, you have to make a bunch of tiny little squares and copy them and cut and paste them. Or make a fake grid system for yourself. Which is, then, what [in my work] begins to relate to Takeshi's stuff, because you’re taking a prepackaged consumer technology -- After Effects or Flash or whatever it is -- and you're trying to figure out a way to make it do something it is not supposed to do. Well, that's not something just we have in common, but what, I think, most good animators or artists do: taking a tool and trying to subvert it in some way.

TM: I definitely began thinking this way in terms of sound. Like stuff that I would listen to -- you know like hacking into old Casios to get much better sounds than were ever made by just pushing the keys on them.

JC: Yeah, exactly. And the other thing about it is that that is just kind of a natural impulse: how could you not want to do that? Like we were talking to Nate Boyce, who teaches at San Francisco Art Institute (sound and video artist who sometimes collaborates with Murata), and how his students just want to make something, you know, "the right way." Like my impulse before I even knew about like NOISE music or anything has always been to do things the wrong way. Like, how can I do this in a way that no one else has. So, I really have a hard time understanding why there are these students who want -- sorry I keep saying, "students," I just mean like younger artists.

MR: That's because now you are a teacher (Ciocci currently teaches in the Electronic Time-Based Arts section in the School of Art at Carnegie Mellon University). [laughter]

TM: Yeah, now you are a MASTER and everyone is a student. [more laughter]

JC: Oh man! [laughing] No, I was going to say that I totally read manuals and stuff so that I know what I am getting into, but I never end up following what the manual says. You know what I am saying?

TM: Do you think that is related to the fact - like, for me, I got into that because I wanted to work at the highest end. Like the consumer level stuff tends to throw away the crap that the higher end studios used ten years ago. And I'm always tempted to do like Spider Man 4 graphics -- but it's impossible, so you have to go in the other direction. [laughter]

JC: Well, that's a good question. I wonder what the impulse is -- like "fuck it, I'll never be as good as Hollywood, so I'll just make my own bastardized aesthetic." Is that what you're saying?

TM: Yeah, I am wondering if that comes into it.

JC: Well, do you think it does for you? You are an interesting example because you are someone who I feel does make really beautiful things that do look "high end" to me, but at the same time, you subvert that -- which is basically, the premise of this show, "PREDRIVE".

TM: Thanks. But, you know, if I had my shit together, I would love to do everything like --

JC: HD [High Definition]?

TM: Like a Hollywood film and totally use that stuff, because you could make insane shit. But to have that brain to get like the 100 people together to get funding or make something that would be commercially successful takes a really unique brain.

MR: Well, you have to be a businessman.

TM: Yeah. But, I just want to stress that the films I love the most are made as independent films -- with the artist working mostly on their own (shooting, directing, animating, editing). But when working with technology --

JC: You're never separated from the think tanks in a way, if you work with technology, so that's what you're saying.

MR: Like larger think tanks? In industry?

JC: Yeah, well even artists like Harry Smith. Even artists who worked independently at some point had to engage with someone in order to get the technology that they had. You know, don't you think?

TM: For sure.

MR: And Folkways picked him up later [referring here to the Anthology of American Folk Music, edited by Harry Smith and produced and distributed by Smithsonian Folkways, 1997]

TM: I mean, in contrast, it's really easy now, you can be a real freak and own a Mac and produce your own videos.

JC: It's so funny you would say that because I just -- well, you know, Girltalk, you know this local guy from Pittsburgh, he's like a mash-up artist who has gotten a lot of attention, huge, but I was just looking at YouTube yesterday and the most popular video on YouTube is a PC commercial by Microsoft in which Girltalk is featured. And you know, he's been around forever. But, what he says on the Microsoft commercial is: "You know computers are the most punk-rock thing that has ever happened in history." At one point, I thought that was really cool, but it's also so cheesy --

MR: After the guitar, excuse me! [laughter]

JC: Right, well, it's like -- you're right, it's [the computer] is just like the next guitar.

Image: Paper Rad, Dark Side of Light, 2008, (Installation shots from PREDRIVE: After Technology)

Image: Paper Rad, Dark Side of Light, 2008, (Installation shots from PREDRIVE: After Technology)

MR: Can I say something before I forget -- Remember when we were talking about your respective backgrounds. For instance, you [referring to Takeshi] came more out of a film tradition, studying animation at RISD. The people you look up to are like, Beckett [animator, Adam Beckett], maybe [Robert] Breer and even artists like Woody and Steina Vaselka, Len Lye. It seems that you have more of a classical interest and background in animation.

TM: Yeah.

MR: And Jacob is this punk nerd coming out of Oberlin, closed up in his room with computers. In the suburbs, with these nerdy kids who are obsessed with colors, psychedelia, and always trying to hack shit open. [laughter]

JC: Yeah, at Oberlin we didn't learn about any of that stuff [i.e. history of animation, experimental film]. I didn't learn about any of that until about two years ago. And even now, I am still trying to learn about all this film history and partially why I am into it [speaking to Murata] is because of your work. And because I know that you and Nate and Ara [Peterson] are inspired by all that stuff [experimental film and animation]. And now I am like, yeah, this stuff is amazing and the films I have seen from this period, I know that that is the stuff that can inspire me. I mean I didn't even know about Oskar Fischinger until a year ago.

MR: So, well this relates to that idea we were talking about earlier in which you were both talking about getting into new technologies by going backwards, and then forward again to like what, for example, HD can do. It seems that it's the urge of wanting to break it [new technology] open outside the lyricism of an industry to which it belongs, i.e. a computer store, an Atari store. So it seems that compositional mode for both of you is to want to crack open technology, to make it do something different than it's intended use -- like you said earlier -- make it go in the opposite direction of the instructional manual. But, at the same time, you use all the history of that technology -- its highest functions (the stuff that's hidden from the consumer). You know, Warhol was like that as well -- wanting to fuck up technology, like with his SONY tape recorder -- wanting to make it do things that are unexpected, while simultaneously simulating the recording industry. For example, he treated television technologies and their industries in a similar fashion: "I'll look like television, but I am going to be hyper-television." It seems that you both have this shared aesthetic where you like to manipulate high technology in a lo-fi way.

JC: Yeah, I think that that's what all these artists did who we look up to historically. Like let's imagine you are one of these artists working at Bell Labs.

TM: Like Lillian Schwartz (animator, researcher in visual and color perception at Bell Labs during the 1970s)

MR: Or, Billy Klüver (electrical engineer at Bell Labs who founded EAT: Experiments in Art and Technology) and Stan VanDerBeek (architect, engineer, and filmmaker who worked at MIT as well as Bell Labs)

TM: And Ken Knowlton [animator and research colleague of Schwartz and VanDerBeek at Bell Labs, Knowlton and VanDerBeek collaborated on Poem Fields (1964-67) at Bell Labs, Knowlton and Schwartz worked together on the film, Pixillation (1970) for Bell Labs]

JC: And like Nate Boyce said -- Nate is going to keep coming up in this interview [Boyce had just performed in Murata's Heavy Light program at Pittsburgh Filmmakers] -- artists got the opportunity to work with Bell Labs through a residency, and they had the choice to either make something Bell wanted them to do, which would showcase the high tech labs, or go another route and say, "fuck you," and that's what I think is the more interesting place. That's why that work stands out, because it simultaneously looks insanely old and dated, but also still completely contemporary and forward thinking. Because the technology used to be high tech, but now it's low tech -- but the ideas are like unique -- no one, in my opinion, has surpassed some of those ideas.

TM: Yeah, like that balance is really key and difficult. Like anyone using that technology trying to make cutting edge stuff -- I am thinking of some of those commercial reels [from Bell Labs] that showcase what those new technologies could do and they look so bad, like the worst stuff. It's like -- well similar to Hollywood's special effects -- give it four years and it looks ridiculous.

JC: It's just about how creative individuals interact with new technologies. Like some people are afraid of it, but then someone like Lillian Schwartz is like, "I am not afraid of this computer and I am going to manipulate it and destroy it." You know, and it's also thinking about it as something that is not precious. Even though there is all this money and power behind it, it's not precious.

TM and MR: Yes!

JC: Like if you go into Best Buy, 99% of the consumers there are so scared, so paranoid about the technology they are about to purchase.

TM: That film of Lillian Schwartz's Pixillation (1970) -- it's so much about her putting together super organic forms -- you know, old techniques, like back-lit ink, next to full on computer generated pixels. I mean, I don't know what she would say about that work, but it seemed that she was trying to understand all those combinations -- natural and computer forms.

Video: Lillian Schwartz, Pixillation, 1970

JC: So let me ask you both something -- based on that Best Buy example, I just gave you -- So maybe when you go into buy a TV, you've worked hard for a month, you have only this much extra money to spend. You don't want to fuck it up, you want to get the right thing. You want your money's worth. And that's a respectable way to think about technology, because you know, this is your extra money. But at the same time, I am someone like maybe because of my -- well, it's not like I am any richer than they are, but there is a slight privilege connected to the way I think about technology. Or, maybe it’s that I don’t care that much about it. I mean I would be a little sad, if I bought an HD TV and it broke, but it wouldn't be the end of the world, though I might have thrown down all my money to buy it. Do you see the question I am getting at? Is there some kind of weird bias that I have toward technology? Like, why do I not treat it as sacred as these other consumers?

MR: Because you are an artist.

JC: Yeah, okay.

MR: You're not just a consumer who wants it for entertainment. You have cultural capital that they might not have.

JC: I guess, but there are other artists who are scared of technology.

MR: Well, if you're not afraid, why won't you break the frame around the giant plasma screen that you are using for the show?

JC: Well, the other screens in the show are smaller, cheaper (150.00 a pop). So, what I am doing with those is I am taking the frame off and smashing it so it looks like broken and fucked.

TM: Are you going to smash the actual monitor?

JC: No, the frame of the monitor and leave the gel screen intact, so it looks like a store in Canal Street that sells --

MR: Damaged screens? [laughter]

JC: Damaged screens -- damaged screen is the perfect term, damaged LCD. But my inner fear or whatever is that I, ideally, should be busting the giant Aquos screen too, but I can't.

MR: Ohhhhhhhh

JC: You see so there's the compromise. There are just certain things that are not going to happen given where I am at -- like professionally or whatever. You know like Matthew Barney could bust a giant Aquos screen, but I can't. It just feels like too much privilege.

MR: Is it privilege or do they (Mattress Factory) want it back?

JC: I would do it, if they let me. But, I think they want to use it for future shows and I completely respect that.

TM: What do they do with other materials, like what if it was wood for a sculpture?

JC: Yeah, they would let you damage that (wood) of course.

TM: But, they wouldn't take that back, the artist keeps that -- isn't it a sculpture at that point?

JC: It is, but...maybe this is like me -- I'm like this timid kid or something. I'm just not ready -- they're so friendly here, I am just not ready to.

MR: Yeah, it feels a bit homespun.

JC: Exactly.

MR: On the other hand, I've instructed them not to keep this technology after the show -- it's just going to be obsolete very quickly. They should sell it and buy to order for the next show. So, to be perfectly honest, your smashing of that monitor should not be such a big deal. It's also a sculptural material.

JC: Well, I want to amend my earlier statement: maybe I am afraid of technology. Maybe even to me this is a precious commodity that shouldn't be fucked with, you know? Because once it gets above a thousand or two thousand dollars, I'm like eeeeh, maybe I'm not ready for this, I'm not there yet. But, on the other hand, Cory Arcangel does these brilliant pieces where he gets the gallery to buy these giant plasma screens. And the difference between LCD and plasma screens is that plasma screens have this "burn problem." If you leave an image on it for too long, it will just burn an image into the screen. So, he buys it and immediately types in his name and the date. And lets it sit there for two days and ruins it. [laughter]

MR: That's great.

JC: And, then it just becomes this object. It is no longer a functional TV; it just becomes this sculptural object then. That's a little different to me, because then that’s all it is -- a sculptural object. I'm still doing something where there's still quite a bit of content that is still separated from the sculptural object of the frame. I have yet to figure out how to merge those two -- like get into true video installation where the sculpture and the video are the same thing. [to Murata] What about you -- you haven't really done anything like that, or? You're not so much dealing with the physicality of the thing?

TM: Yeah, I have just been into the space of video. I really wanted to stick with video and not have the box or whatever it’s in become part of the work, but as a shout out to Chris [Perez] of Ratio 3 who is coming [to the PREDRIVE opening] -- he's been just been hustling to sell video, it's a concept, a crazy thing to try an sell, but he's been able to do it. But he's got these collectors who are awesome, who don't care about whether or not it's an object, like coveting something. They're actually buying something that isn't physical.

JC: Yeah, and they know they're not buying something physical.

MR: Well, you know Matthew Barney did it [sold and still sells video] and Christian Jankowski, and -- you know, they sell editions.

TM: Yeah, well Barney is like a brand -- insured value.

MR: So, aren't you [to Ciocci] -- by holding back from smashing that plasma screen, you're missing the opportunity of matching that kind of dealer who you appreciate -- one that would invest in just an idea -- one who would value that act? So, in a way, I challenge you -- I really think you're holding yourself back by not smashing that frame.

JC: I've got two days [before the PREDRIVE opening]. [Laughter]

MR: I think you should smash it.

Takeshi Murata pushes the boundaries of animation and psychedelia with sophisticated code-based image processing. In the hypnotic video installation Monster Movie, a B-movie decomposes and reconstitutes 30 times per second, becoming a seething, digital morass of color and form. "Murata's particular genius is an almost alchemical ability to transform forgotten relics of pop culture into dazzling jewels," comments ARTFORUM. Takeshi has participated in numerous international gallery and museum exhibitions. Recent exhibitions include a solo project with the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden (Washington DC) and participation in Automatic Update at the Museum of Modern Art (New York). Takeshi is represented by Deitch Projects (New York) and Ratio 3 (San Francisco).

Paper Rad synthesizes popular material from television, comics, video games, and advertising -- allowing these materials to contextualize and cross-reference each other. The three primary members are Jacob Ciocci, Jessica Ciocci, and Ben Jones. They make comics, zines, video art, net art, MIDI files, paintings, installations, and perform in a variety of bands. Although they continue to publish their own zines, music, and online content, they have shown at galleries including Pace Wildenstein and Deitch Projects and have exhibited in Pittsburgh, New York, Philadelphia, Providence, Boston, as well as in Norway, Germany, Canada and England.

Melissa Ragona's critical and creative work focuses on sound design, film theory, and new media practice and reception. Her current book project, Readymade Sound: Andy Warhol's Recording Aesthetics, examines Warhol's tape recording projects from the mid-sixties through the late-seventies 70s in light of audio experiments in modern art and current practices in media technologies. Her essays in film and sound criticism have been published in the MIT Press Journal, October; Duke University, Illinois and Ashgate presses. Ragona's catalogue essays on contemporary artists have included Heike Mutter, Ulrich Genth, and Christian Jankowski. She has also written for Art Papers and Frieze magazines. Ragona has curated film and video exhibitions and festivals for national and international venues, including a production of Miranda July's Swan Tool, as well as the films and videos of experimental filmmakers Peggy Ahwesh, Pat O'Neill, Yvonne Rainer, and Benton Bainbridge. She currently teaches in the School of Art at Carnegie Mellon University.

that's awesome, I really need some wow gold. I've been looking everywhere for a good price.

ps. nice interview, really enjoyed it. Video will never and should never be sold. It's a bastardization. It's like charging someone for air. We should all be working as hard as possible to give everything away for free. Video is one of the easiest things to give away for free, except maybe music, or text….hey maybe in 100 years you'll be able to get a car for free. Or maybe next week.