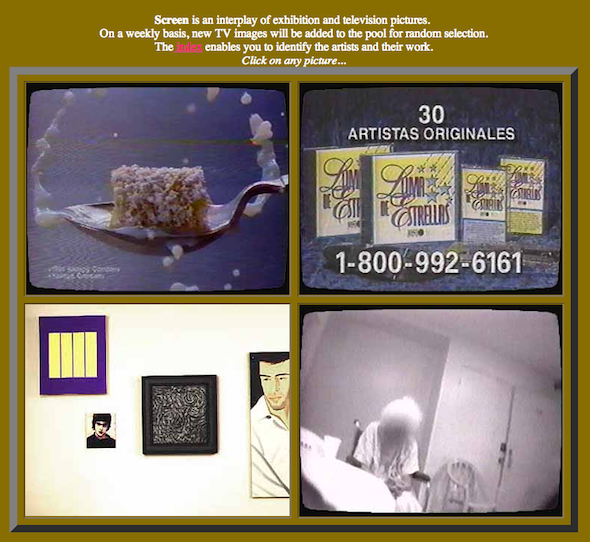

Image of äda 'web page produced for the exhibition "Screen," 1996.

In 1996, curator, critic, and educator Joshua Decter colorfully defined "media cultures" as "a euphemism for how we reproduce ourselves, as a society, into a spectacular—i.e., ocular and aural—organism whose viscera has become technology itself."

Throughout his career, Decter has paid special attention to media cultures and their relationship with the public sphere, developing a curatorial practice that has long been distinguished by its openness to adjacent new media and net art practices. Beyond spectacle, his use of websites, apps, and other technological apparatuses sheds fresh light on artists and artworks generally considered to be decidedly analog.

I invited Decter to walk me through three curatorial projects, all ambitious group shows, that exemplify his career in digital and AFK spaces. In each, the artwork is mediated—either by conceit, didactic, or display—so as to variously diffuse and emphasize the image, addressing the nature of art and its publics under the condition of networked technologies.

"Screen," Friedrich Petzel Gallery and äda 'web

January 19—February 24, 1996

For the exhibition "Screen" at Friedrich Petzel, I mentioned to Benjamin [Weil, co-founder of early online art website äda 'web] that I was curating a painting show thinking about the relationship between painting and television. It was a kind of conceit, in terms of theories of velocity and reception, not in a way that was meant to be didactic or academic, but more playful... I thought, why not work with äda 'web to build... a virtual extension of the exhibition? This work is still online.

It wasn't groundbreaking as an interactive interface, but it was meant to ask, "how does one articulate a curatorial structure on the web?" [The online project] involved the text being integrated into the visuals of the exhibition; it allowed people to click on individual paintings that would then become screengrabs from television, paralleling through interaction the actual television in the site of exhibition, and the interpenetration of images of television and images of the paintings... in a video catalogue produced alongside.

These were screengrabs from news images, commercials, sitcoms, what have you. Our developer, John Simon, built an algorithm so that there was a randomness to the [screengrabs] and the paintings. We wanted to make it more elaborate—that there would be a real-time feed from a television signal, an endless uploading and then grabbing of images—but for some reason technically we weren't able to accomplish that with the means that äda 'web had at that time.

Participating artists: Richard Artschwager, John Currin, Nicole Eisenman, Gaylen Gerber, Peter Halley, Mary Heilmann, Peter Hopkins, Alex Katz, Byron Kim, Jutta Koether, Bill Komoski, Udomsak Krisanamis, Jonathan Lasker, Glenn Ligon, Allan McCollum, John Miller, Laura Owens, Jorge Pardo, Elizabeth Peyton, Lari Pittman, Sigmar Polke, Richard Prince, Gerhard Richter, Matthew Ritchie, Alexis Rockman, Gary Simmons, Rudolf Stingel, Philip Taafe, Luc Tuymans, Christopher Wool, Chris Wilder, Sue Williams.

"Transmute," MCA Chicago

July 24—September 19, 1999

Installation view of "Transmute" at MCA Chicago in 1999; at center, the virtual curator kiosk.

MCA Chicago was inviting outside curators, maybe even one or two artists, to interpret the collection. Not knowing it well, I was tentative about this, but decided I would do it if we could figure out a way to broaden its scope in terms of outreach, to move beyond parochial education programs, because, in the end, this was seen as an opportunity to re-energize the collections. I wanted to work with an interactive programmer to design a dual system: a virtual artist component and a virtual curator component. Both were available on kiosks in the site of exhibition and online.

A screenshot of the virtual curator application created for "Transmute."

For the latter, I selected a John Baldessari work from the exhibition—this would be an opportunity for people to engage with a Baldessari in a conceptually consistent way with how John actually makes his work. Appropriating. Selecting. Reorganizing. Doing something to public or private domain images. People could submit their own images that would be plugged into a virtual template, basically of the Baldessari work, so that one could manipulate the image. These public submissions were not necessarily meant to be as art, this wasn't about endeavoring to transform people into artists per se, but to offer a sense of what it means to actually make a work of art with images.

To me, the more exciting element was the virtual curator, in which the public had an opportunity to re-curate the exhibition, not in terms of selecting new works—I wanted to do that, but the museum could not give me access to other pieces—but reinstalling extant works in the show. From what I understand that had not been done before. I was very excited about this, still today when I think of what other things museums could have done, what roads they could have taken, but didn't.

This was on MCAChicago.org until the mid-2000s, but then it disappeared. Apparently, no public archival version exists.

Participating artists: John Baldessari, Matthew Barney, Chris Burden, Jeanne Dunning, General Idea, Gilbert & George, Mona Hatoum, Gary Hill, Jim Isermann, Mike Kelley, Jeff Koons, Barbara Kruger, Charles Long (with Stereolab), Rene Magritte, Bruce Nauman, Tony Oursler, Jorge Pardo, Jack Pierson, Richard Prince, Mel Ramos, Allen Ruppersberg, Jim Shaw, Cindy Sherman, Lorna Simpson, Liam Gillick, John Miller, LOT/EK, Noritoshi Hirakawa, Grennan and Sperandio, Miltos Manetas, Julia Scher, Fariba Hajamadi, Sam Samore, Mans Wrange and Gerwald Rockenschaub.

"Dark Places," Santa Monica Museum of Art

January 21—April 22, 2006

Install view of "Dark Places" at Santa Monica Museum of Art, 2006.

Developing a framework for "Dark Places"...I was thinking about noir, urban psychogeographies, and remapping space, coming out of the ideas of [architecture critics] Reyner Banham and Anthony Vidler. And that led me to thinking about I don't simply want to curate an exhibition where I invite artists whose practices had been re-working one space or another. Instead, I thought it would be more compelling to rethink the format of presentation in a fairly radical way.

Installation view of "Don't Look Now" (1994) at Thread Waxing Space.

What allowed me to do that was going back to an earlier exhibition—my first, technically—in 1994 called, "Don't Look Now" at Thread Waxing Space. For that, I invited 100 people (artists, writers, and other cultural producers) to submit one image in 35mm slide form. I worked with a designer to build an environment for 80 slide projectors, which would run simultaneously, continuously. That was about using the available technology of mediation then—the slide projector—in relation to the movement from some kind of "real life" to mediated space.

So, I thought back to 1994 in 2005-06, when I began developing "Dark Places." I thought, what is the technology of mediation that's available, what are the mediating devices? Of course, it was digital imaging. (I should note that the video catalogue for "Screen" was produced with [the nonlinear video editing system] AVID, but in 2006 we were talking much more advanced digitization.) I reached out to servo, a group of architects, who were working with information-based, systems architecture. I collaborated with them for a couple of years on this apparatus of display, presentation, and projection, an apparatus that would allow me to curate in a quite different way.

Installation view of Dark Places (2006) at Santa Monica Museum of Art.

For the show itself, I invited a large group of artists to have their work digitized—ranging from one image or sequence of images to an entire video or digitized film—and I broke their contributions down into eight quasi-autonomous "scripts." All were presented via this display apparatus, the collaboration with servo—this kind of thing, which had a thingness or an architectonic sculpturality. And each node was an opportunity to curate a sequence of these works, presented via screen. So there were eight exhibitions contained within one, but, of course, taken as a whole, there was a lot of stuff happening at once.

Clearly, I wanted to push things as far as one could in terms of mediation, through digitization, sequencing, scripting, simultaneity of audio/visual information and effect, challenging the autonomy of works in a way that I thought was somehow commensurate with how art operates digitally, virtually, within the broader culture, amidst distraction. I didn't want to produce distraction, but I wanted to see how far things could go, in terms of velocity, attention, focus, and de-focus.

Participating artists: Vito Acconci/Acconci Studio, Franz Ackermann, Francis Alÿs, Michael Ashkin, Jaime Ávila Ferrer, Dennis Balk, Matthew Barney, Judith Barry, Thomas Bayrle, Julie Becker, Douglas Blau, Monica Bonvicini, Daniel Bozhkov, Mark Bradford, Miguel Rio Branco, Troy Brauntuch, Candice Breitz, François Bucher, Sophie Calle, Eduardo Consuegra, Jordan Crandall, Teddy Cruz, Jonas Dahlberg, Stephen Dean, Anne Deleporte, Diller Scofidio, Sam Durant, Anna Gaskell, Douglas Gordon, gruppo A12, Fariba Hajamadi, Pablo Helguera, Noritoshi Hirakawa, Julian Hoeber, Emily Jacir, Christian Jankowski, Vincent Johnson, Mitchell Kane, Joachim Koester, Glenn Ligon, Dorit Margreiter, Fiorenza Menini, John Miller, Muntadas, Paul Myoda, Yoshua Okon, Catherine Opie, Lucy Orta, Hirsch Perlman, Raymond Pettibon, Richard Phillips, Richard Prince, Raqs Media Collective, Alexis Rockman, Julian Rosefeldt, Aura Rosenberg, Peter Rostovsky, Sam Samore, Paige Sarlin, Julia Scher, Gregor Schneider, Allan Sekula, Andres Serrano, Nedko Solakov, Doron Solomons, Wolfgang Staehle, Javier Téllez, Anton Vidokle, Eyal Weizman/Nadav Harel, James Welling, Wim Wenders, Judi Werthein, Charlie White, Måns Wrange, Jody Zellen, and Heimo Zobernig.

A graduate of the Whitney Independent Study Program, Joshua Decter is a New York-based writer, curator, theorist, educator and editor, whose writings have been extensively published over the past twenty-five years.

Decter founded the M.A. Art and Curatorial Practices in the Public Sphere program at USC in 2011. A collection of his writings, titled Art is a Problem, was recently published by JRP-Ringier. Last week this saw a launch in New York, with events in Los Angeles, London, Vienna, and Berlin forthcoming.

Thanks for this, Zachary. Some thoughts on these projects are at http://www.tommoody.us/archives/2014/05/06/joshua-decter-gallery-art-critic-as-new-media-artist/

May 14, 2014

Dear Rhizome readers,

At 51 years old, I’m not quite in the grave yet. So when an opportunity to defend my work as a writer, critic, curator and educator for nearly thirty years presents itself, I’m not going to shirk my responsibilities. So how disappointing it was to find that artist Tom Moody wastes our precious time and attention with a diatribe about yours truly that not only contains factual errors, misunderstands important aspects of the historical interrelationship between contemporary art production, new media and the Internet since the 1990s, but also misrepresents my work as a critic, writer, curator, educator and organizer.

Mr. Moody would have been well served to have first read my JRP|Ringier book, Art is a Problem: Selected Criticism, Essays, Interviews and Curatorial Projects (1986-2012), (http://www.artandeducation.net/announcement/art-is-a-problem-joshua-decters-new-jrpringier-book-and-book-events/), which contains an extensive overview of my activities.

To be clear: I’ve sustained negative, positive and every other kind of criticism about my curatorial projects for years, but one can only take seriously those critiques that are based in facts— and, that – god forbid – actually take into account the ideas that I’ve published about these exhibitions.

Moody offers a snarky and inaccurate title for his post, “gallery art critic as new media artist,” and leads off claiming that a “common thread is The Curator as Artist.” Well, I’ve made a couple of public statements (in print and elsewhere) since the 1990s decidedly rejecting the notion that what I’ve done as a curator has anything to do with making art. The consensus is that I’m a curator who has experimented with formats of display and exhibition design, although a couple of people fantasize that this means I want to be an artist; Moody is apparently a member of this fringe. I’ll discredit this assertion again: it’s curating, nothing more, nothing less. What’s more, there’s nothing in my conversation with Zachary Kaplan of Rhizome that either explicitly or implicitly suggests that I’m endeavoring to make art with my curating, so I think that Moody is deliberately misreading my comments, as well as Zachary’s remarks.

Moving on to a factual error regarding the Screen exhibition: I did not “place TV cameras in the room to film the works.” Rather, I took photographs of the installation of artworks, digitized these images, and worked with an editor on an AVID system at a professional studio to generate a video catalogue of the exhibition. This video catalogue was distributed as the only catalogue of the show, and was also played on video monitors within the gallery during the run of the show. These processes of production were clearly indicated in the press release for the show— and, in my new book within the chapter that addresses my curatorial projects. In terms of the artists I included in the show, some were “top painters of the day,” but others were not; it was a generational mix, and a mix of established, underknown, and emerging artists.

In terms of my biography: I began writing for Arts Magazine in 1985, at the invitation of the late Richard Martin, who was the editor of the magazine at that time. I would argue that both my writing and Arts flourished under Richard’s editorship during the 1980s, and in fact I selected two essays that I published in 1986 in Arts to be included in my new book. My role at Arts was already reduced somewhat by the early 1990s, as I became increasingly engaged in writing for other magazines (including Artforum), and with teaching, organizing and curating. Moody’s claim that I had “gatekeeper” status is rather farfetched; maybe I broke and repaired the gate a few times, but that’s about it.

Moody’s sloppy critique of the Screen exhibition fails to acknowledge the fact that the exhibition was an attempt at a playful reflection on the different velocities (slow, fast, etc.) involved in encountering/perceiving television and painting within the same cultural context— this is clearly indicated in the press release for the show, and the video catalogue. My argument in that show was not to suggest that painters were literally working at the same speed as television (or video artists, or new media artists, etc.), but rather to propose that we – as viewers, as publics – were experiencing/viewing painting within the broader context of mass media culture, and that there was a disjunction in temporal velocities and perceptual conditions in relation to watching television and viewing paintings. That’s exactly why I placed, in a rather tongue-in-cheek gesture, a television hooked up to cable with a remote control for people to watch in the gallery: to amplify these differences. Moody seems to have completely misunderstood this situation, even though it was clearly articulated in the press release, the video catalogue, and in my new book. Moody refers to the show as a “cattle call,” but this is not how Peter Schjeldahl (a professed lover of painting), characterized it at the time in his extensive review in The Village Voice: http://www.mutualart.com/OpenArticle/Screenery/4F21725292E4D4BC

In terms of the web extension of the Screen exhibition (which was produced on a limited budget, like basically every else at ada web in 1996), it actually looks much better than Moody will admit. It is the images of the paintings that pop out visually, while the TV images actually recede: exactly the opposite of what Moody asserts. And there’s a reason for this: the digitized images of the paintings were shot at a much higher resolution than the screen grabs from television. And this difference in image resolution is still discernable now on the Internet, nearly 20 years later.

Moody’s comments on the Transmute show at the MCA Chicago are even more haphazard, and I think it’s clear that he did not see the show. He writes: “Decter feels that his ‘virtual artist’ and ‘virtual curator’ kiosks at MCA Chicago in 1999 differed from the familiar interactive displays of museum education departments across the country. This seems wrong but I can't back it up with hard stats.”

Does Moody really expect this kind of criticism to be taken seriously? The bottom line: in 1998-1999, when this exhibition was developed (with an interactive designer and programming team, by the way), the MCA Chicago had no interactive educational elements in their museum whatsoever. This was an entirely new thing for this particular museum. And I do not recall seeing anything like the ‘virtual curator’ and ‘virtual artist’ interfaces in other museums at that time.

Furthermore, contrary to Moody’s claims that somehow this misrepresented John Baldessari’s work, the artist himself agreed to have a particular piece from the MCA’s collection used as the framework for a new kind of interaction with the museum’s publics. Baldessari was excited about it, and understood that it did relate to how he went about producing his work. Moody also brings up Google SketchUp; well, SketchUp debuted in 2000 (before it was acquired by Google in 2006), but the Transmute exhibition opened in 1999, so there was no way that my programmers had access to that software- just to make this perfectly clear, if there was any confusion created by Moody’s remarks. And furthermore, the point of the interactive programs for Transmute was to offer another mode of educational engagement for the museum’s publics. And so by providing a platform for audiences to participate by experimenting with reinstalling their own virtual versions of the exhibition, or remaking their own virtual versions of the Baldessari piece, I thought that this was an interesting way to challenge the parochial approaches to museum education in the 1990s. I think we were somewhat ahead of the curve with our ‘virtual curator’ and ‘virtual artist’ programs, specifically in terms of the context of museums and museum education departments.

Moody’s remarks about the 2006 Dark Places exhibition are even more cynical and strange, accusing me of joining the architectural community’s “ongoing war against artists.” Huh? I guess that Moody missed the fact that numerous artists – more than 70 - were willing participants in the show, and that I continuously updated all of the participants about every aspect of the exhibition design, architecture and display system. The participating artists understood the situation and engaged fundamentally not because inclusion in such an idiosyncratic exhibition would necessarily help their careers, but because they were open to an experimental curatorial framework. In other words, they sufficiently trusted me, and the architects with whom I designed the show. Why is it so difficult for Moody to accept this? And did Moody actually visit the show at the Santa Monica Museum? The most important thing is that artists were enthusiastic about the show when it opened. There are video documents of participating artists speaking about it in very compelling ways, within the context of public panel discussions. Interestingly, on one of those panel discussions, new media theorist Lev Manovich also spoke, adding his unique perspective on the history of new media art in relation to the exhibition. And Moody’s accusation that I used the gallery system as a “salad bar for…new media exploration” is just dumb, misleading and insulting. Ironically or not, some of the over 70 participating artists weren’t represented by galleries at the time. And to demonize the gallery system – which also includes some new media artists, by the way – just seems counterproductive.

Finally, as someone who met and befriended folks such as Wolfgang Staehle, Benjamin Weil and Mark Tribe when they were just starting their respective endeavors (the thing, ada web, and Rhizome) back in the 1990s, I’m very aware of the divisions, overlaps and interrelationships that exist between the wide range of art practices, media, discourses and social networks that constitute the various spheres of art production that have evolved over the past couple of decades. Contrary to Mr. Moody’s assertions, these various “fields” have indeed engaged in critical conversations and debates over the years, particularly in relation to what we mean by Internet Art, which is still being debated (witness the current Post-Internet Art discussions).

Thanks for your time and attention in our already saturated attention-economy.

Sincerely,

Joshua Decter

New York

Mr. Decter points out a factual error in my post – I wrote that in his "Screen" show he "placed TV cameras in the room to film the works." I updated the post to describe more accurately how video images of the works appeared in the gallery. Apologies for the error.

Otherwise, I think we mostly have differences of opinion, not fact. Mr. Decter's sense is that virtual curator and virtual artist displays aren't (or weren't) common in museum programming; my sense is that they are (or were). Who did them first doesn't really matter if they are unhelpful, as in overly reductive, ideas. My point in mentioning Google Sketch-Up wasn't to say it was around in 1999. Clearly it wasn't. It was to make a connection between what Mr. Decter was doing with then-current 3D software and what artists are still doing with virtual "white cube"-placed objects ("[reducing the slow] process of artistic thought and individuation of … physical collections to simplified mix and match objects," I wrote in the post). Yesterday's unfortunate idea is today's unfortunate trend.

I haven't read Mr. Decter's book, the release of which roughly coincided with this Rhizome post. Here's hoping he'll be joining the conversation on the vagaries of post-internet art, or po-net, as some are calling it! These issues are too important to leave to Hollywood collectors.

One issue of fact that interests me in this discussion - was the "virtual curator" concept actually adopted elsewhere around the time of the MCA show? If so, where?

There was definitely a lot of this: http://www.artchive.com/cdrom.htm. i.e. art encyclopedias on cd-rom, collection-specific, image-only. Our conservator Dragan was telling me about a few VML-based (?) systems. Perhaps he can weigh in…

I was just mentioning that the images of the "Virtual Curator" I have seen give the impression it could have been implemented in VRML.

On the other hand, this type of Gouraud shading was present in all kinds of interactive 3D graphics environments around that time, VRML was just the most easily accessible choice.

However, if the Virtual Curator was indeed created using VRML, I'd like to lay my hands on it …

Dragan- I didn't see this conversation in the Spring, but the person who was hired to oversee the design of the interactive 'Virtual Curator' and 'Virtual Artist' components of my exhibition project, 'Transmute,' was Ben Chang. Here is a description of the technology on his website (he teaches at RPI), and it does seem to have involved VRML: http://www.bcchang.com/design/transmute/index.php

I'm actually endeavoring to get the MCA Chicago to reconstitute the online version of 'Transmute' in some way, although they claimed two years ago not to have located the original files yet. Their exhibition archive doesn't go back before 2000 (inexplicably), and this show happened in 1999. I will be contacting the museum again, although it seems to be an institution that is not particularly invested in their Internet presence, the potentials of interactivity, etc.

I would love for 'Transmute' to become operational again, in some way, because to me that is one way to address the challenges of preservation: producing the possibility of sustained and sustainable interfaces.

If you have any ideas, please let me know. Thanks.

All my best,

Joshua