.png)

Jon Rafman, A Man Digging (2013), Single channel HD video

Jon Rafman uses the intricate tableaux of Rockstar Games' Max Payne 3 as cinematic source material for his new machinima work, A Man Digging (2013). In this meandering and Robbe-Grillet inflected narrative, Rafman ruminates on the simulated sunbeams glinting through favela windows within the game, a melancholy sunrise in a deserted subway car, a heavy fog over a slate grey harbor. He can only do so, however, after killing every character—whether enemy or bystander—in the scene. In this way, Rafman makes visible the tension between the game as object of contemplation and the game as a continuous stream of connected events.

Although many makers outside of the industry have used video games as source material—Peggy Ahwesh, JODI, Eva and Franco Mattes, and Phil Solomon, to name a few—A Man Digging highlights a particularly frustrating issue in contemporary game design: namely, a pushy Artificial Intelligence system that goads the player into constantly responding to the checkpoints, achievements, and goals that are all in the service of what tends to be called a game's "narrative." Although these events don't necessarily develop plot or characters, they are seen as central components of driving (or forcing) the player toward a sense of completion and finality that can only be accomplished through linear gameplay. As a result of this insistent narrative-centric design, players are prevented from exploring the potential for triple-A games to take on the unique, interactive potential to create contemplative and self-reflective video game environments.

When playing Rockstar Games' Red Dead: Redemption, for example, I was always bothered by the way the game would interrupt me. Atop my horse, I’d want to admire the stunning vistas of the simulated Southwest and watch the cotton-tuft clouds hovering above big-sky country. The designers—or at least some of them—clearly wanted me to gaze upon this virtual splendor, just as one would meditate on a painting by Thomas Moran or Albert Bierstadt. However, the game’s AI would continually interfere, summoning cougars or coyotes, escaped convicts or roadside bandits, to ruin my perfectly good respite. Perhaps this was also some historical accuracy intended by the designers of RD:R, subtly educating players that the West in 1911 was still teeming with chaos. In other words, if you sat still for too long, you’d get eaten alive.

But the same style of “pushy” AI can also be found in Bethesda Studio’s Skyrim. Beneath every moonlit aurora borealis that shimmers across a creek bed lurks a malevolent frost dragon. In such a situation, a player can never become just an ordinary spectator, focusing attention on the game as a perceptual challenge and an aesthetic experience, but instead must always play the hero. In these moments, games abruptly breaks the focus on their immersive graphics in order to insist that the player take action. The environment is presented only for the sake of distracted consumption, not for contemplation. Instead of rewarding a player for becoming invested in the beauty of the game environment, games punish the player if they deviate from the primary goal at hand.

Irrational Games, Bioshock: Infinite (2013)

Rafman’s piece does not explicitly address the need to undermine narrative, but it does suggest that games could be built to accommodate a more contemplative player. To date, games typically only reward a player’s focused attention on their environment through cleverly placed “easter eggs” or some kind of “achievement.” In Bioshock: Infinite, for instance, a curious player deviating from marked checkpoints will be rewarded with brief vignettes. These cut scenes sometimes offer up narrative information, such as the receipt of a telegram containing instructions for the game's character, but they are at their most captivating when they simply allow the moments of respite and aesthetic contemplation, offering insight into the overall patina of a game world.

This being said, some artists and developers have designed games that revolve around fleeting moments in order to create spaces for contemplative play. Most of these titles reward players for slowness, or prolonged stillness. These games also entice players to think about the game as an ongoing process, enticing players to come back to it after several months of not playing. Within these games, a domineering AI doesn't interfere with the whims of a player, and as a result these games encourage players to think about games in a way that isn't primarily focused on narrative.

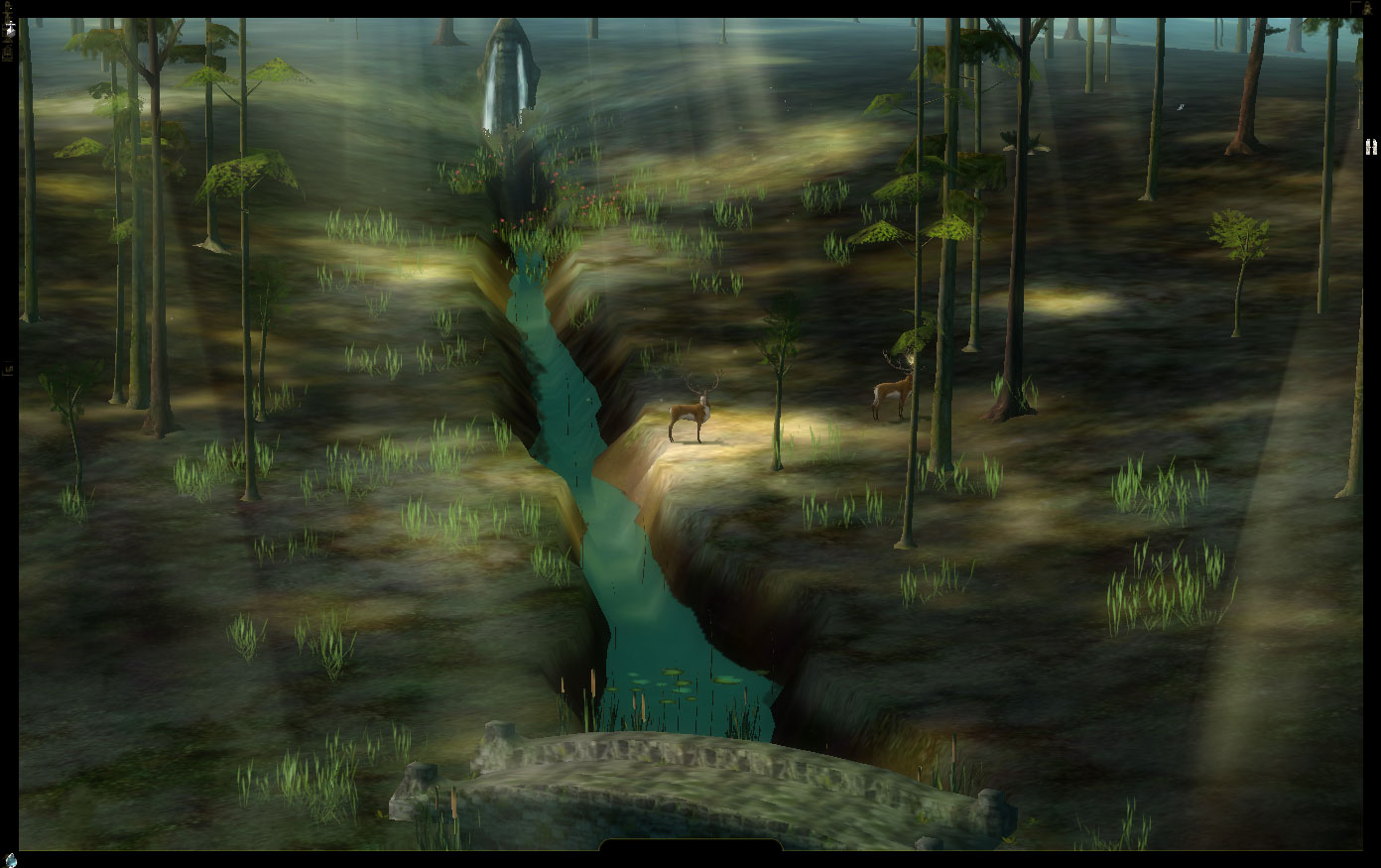

Tale of Tales, The Endless Forest (2007)

A fitting example of this is Tale of Tales’ Endless Forest (2007). This interactive screensaver allows players to control an elk-like creature through various locations and vignettes under a dense, mythical forest canopy. Players interact with other elks over a network and communicate through non-verbal gestures like bowing, stomping hooves and dancing. Although interaction is a central component of the game, an equally important element is the way the game rewards players for free-ranging exploration and stillness. In order to activate certain areas of the forest, the player must remain still, allowing their avatar to come to full resting position. The longer the player remains in these calm states, the more the scene reveals itself to the player.

On top of rewarding players for their stillness, Endless Forest also entices players by integrating an element of downtime that few games would usually implement. The more time a player has spent online (either allowing their computer to remain passively connected, or in exploring the forest), the more their avatar visibly ages and matures. At first, the player's elk is only a fawn, but as the game records their participation, the avatar grows into a sagacious beast. This element of Tale of Tales’ design indicates to the player that their prolonged experience of stillness and rest – both on the part of the player and on the part of their computer going to sleep – will result in noticeable character development, suggesting that patience and contemplation are virtuous qualities of a player.

Another notable example can be found in the critically lauded Journey, developed by thatgamecompany. In this title, players awake in the desert surrounded by gravestones and ruins. As the player moves toward intricate and massive slabs of broken masonry, they encounter floating pieces of fabric that encircle them and provide temporary flight. As in Endless Forest, players find anonymous companions with whom to explore the ruins of this game. Through activating eroded altars, pillars, and frozen columns of fabric with their avatar's voice, the player uncovers a simple narrative about an ancient civilization that sought refuge in a distant illuminated mountain peak. The player then works alongside their unnamed partner to reach the summit through perilous trials and dreadful conditions.

thatgamecompany, Journey (2012)

During this relatively short adventure, players can either choose to advance from scene to scene without the assistance or company of a sidekick, or else collaboratively explore the environments of the game. As the game progresses, however, players have to stick together and sing to one another to enliven each other’s spirits in order to avoid freezing into immobility. This simple gesture brings players together, not just to assist one another, but also to playfully communicate a mutual bond that could only happen through a networked video game.

The beauty of Journey does not just come from its incredible visual design, or from its lack of a pushy algorithm. Its gameplay allows players to collaboratively linger in luscious surroundings. The simple joy of gliding alongside your companion across the glimmering sands of Journey’s environment is captivating in a way that is richer for being shared. Within certain moments of the game, the camera is purposefully positioned to focus the attention of the player toward vast romantic vistas. During one particular scene, players speed along a sloping dune through a once-palatial space, catching glimpses through sun-soaked archways of an abandoned city nestled in the valley below. This moment references the popular game motif of an anxiety-driven downhill chase scene, but here it has been repurposed as a meditative experience for contemplating the unforgiving forward march of time.

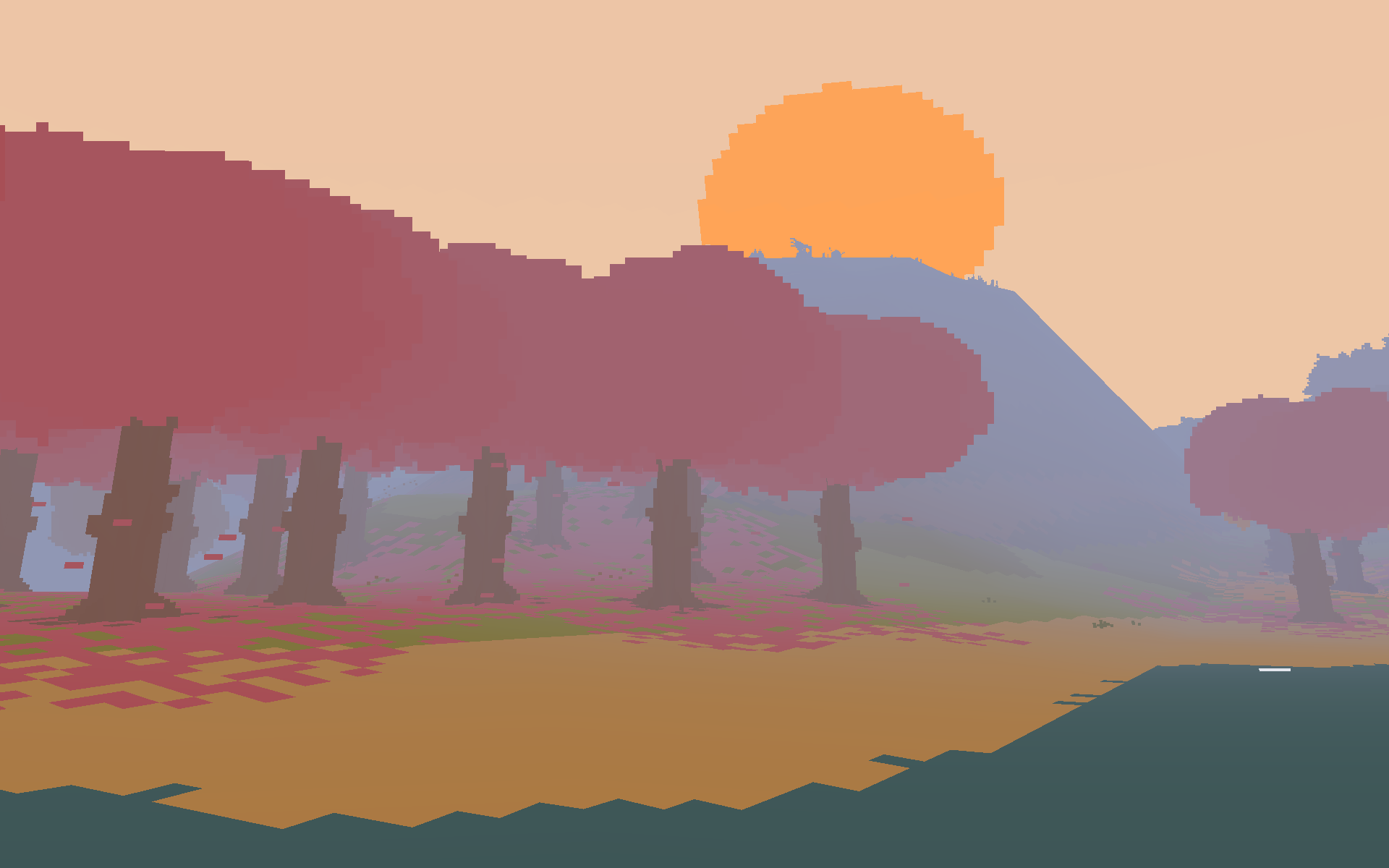

Similarly, Ed Key and David Kanaga's Proteus also uses the motif of a meandering landscape in order to ruminate on the passage of time. Proteus, however, is less concerned with narrative than Journey, in that the primary experience revolves around exploring soundscapes generated by a low-bit, procedurally generated island. The player encounters various creatures and totems that have specific tones that all contribute to a vibrant, synthesized soundtrack. The score then dynamically changes as players explore the topology of the island. Like Endless Forest, players are encouraged to stand stationary in specific moments of the landscape in order to affect the visual and aural experience of their surroundings. One such instance involves standing within a circle of figures that resemble shaman of some sort. After watching the sunset, the distant stars shimmer vigorously and further texture the nocturnal harmonics.

Ed Key and David Kanaga, Proteus (2013)

As the player explores the island further, they find a concentration of circling particles that creates a portal into another season on the island. Each season then has its own unique sound, adding new layers and new interactions to explore. In Fall, the falling leaves from the trees blip upon hitting the amber colored ground. In Spring, the light showers create twinkling arpeggios that lilt atop the dense chords of blossoming flowers. In a nod to Vivaldi's masterwork, Key and Kanaga offer a new aural texture for each season. In doing so, they invite players to consider the changes that occur to the landscape and to themselves, while frolicking through luscious hilltops and valley meadows.

All three titles create contemplative space within the video game as a way to challenge and present alternatives for Rafman's digging man. The structure of Endless Forest rewards stillness and open-ended exploration, in marked contrast with the irrepressible, attention-demanding narratives that occur in triple-A titles. Journey builds on this strategy with a structure that encourages collaborative lingering, engendering shared contemplative experiences within a simple narrative structure. And Proteus abandons narrative entirely, while offering a rich sensory experience. In particular, Proteus suggests that the affect of the virtual environments presented in games is not solely dependent on their graphical similitude to the physical world. Instead, all three of these games offer oases of respite within a wasteland of aggressive blockbusters, creating contemplative spaces in which to approach a kind of interactive rapture.

http://www.iainmaitland.com/MOV.html#deerhunter

http://michaeldemers.com/theskyisfalling.htm