Recently, Rhizome featured vector animations by Dov Jacobson that had surfaced at the XFR STN open-access media conservation project. Another standout work from the same videotape (RYO Gallery’s 1986 EVTV2 compilation) is the sensorially intense Sunflower Geranium (1983) by Don Slepian. The eight-minute 40-second video documents a live performance by the artist in which he used a custom array of specialized hardware and software to mix synthesized video imagery and original electronic music for a live audience. As Slepian, who is now a performing classical keyboardist, told Rhizome via e-mail, “I was a live performing VJ twenty years before the term existed." While the nature of performance of course doesn’t allow us to replicate the live experience, we’re thrilled that this video record of Sunflower Geranium can now find a new audience. After thirty years of advancements in technology, it’s difficult to imagine what went into Slepian creating these performances. Luckily, he was kind enough to answer some questions about performing with the system he created.

GM: Can you talk about the technology you used to create Sunflower Geranium?

DS: I gathered and developed a Live Performance Theatrical Visual Instrument in the early 1980s in a tiny apartment in Edison, NJ, as a continuation of a life-long fascination with the tools and techniques of electronic performance art.

I raised the money to create this studio from a private investor in 1983. I produced a series of shows featuring "Live Theatrical Image Processing" both in the USA and in France that anticipated the emergence of video VJ's twenty years later. Despite the best efforts of myself and two dedicated co-workers I failed to find a market for either the video stills or live video animation services. By 1986 I had to close the business and move on to other work. This was one of many financial failures in my life, but at the same time it represented a series of technical triumphs. At age 30 I had perhaps the most advanced and sophisticated privately-owned live-performance visual instrument in the world. I managed to develop and sustain it for several years of theatrical performances.

GM: What sort of programming went into producing the different effects?

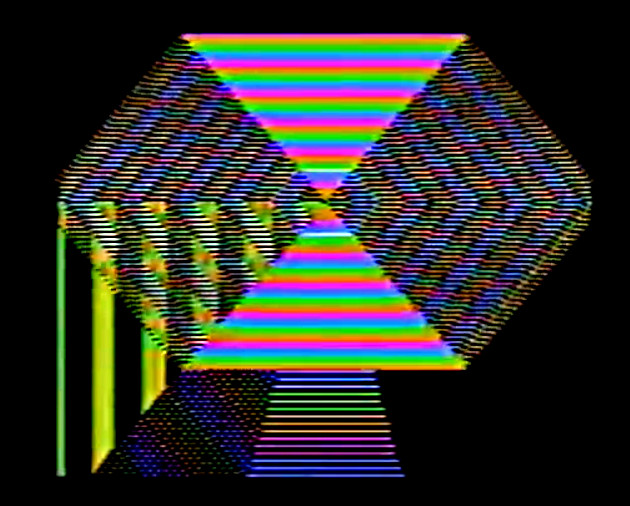

DS: The opening visual motif is a pair of moving dot fields in contrary motion generated by a custom-modified Chromaton analog video synthesizer,[1] with colorized analog video feedback giving the rippling 3D effect. The colorization was done with a special effects keyer[2]; the video feedback was generated with an enclosed rescanning camera-monitor chain of my own design, a high definition monochrome camera with a good zoom lens facing an analog video monitor in a light-proof box, designed for controllable live-performance optically-modulated video feedback.

Behind this crude "star field" is an Apple II+ animation, really a score that I performed live.The computer that I used was specially souped up: not only did it have an accelerator board that made the graphics run much faster,[3] it also had extensive modification that allowed the computer to produce video that could be mixed with other sources and recorded.[4] This changed everything.

The score, which was called "Many Roads to L," comprised spiraling enlarging color-shifting visual echos of the text character "L". It was created in Brooke Boering’s wonderful CEEMAC graphical language, which was used to create very fast and highly responsive animations that could be instantly switched to music.[5] I would use the CEEMAC fire organ animation demonstration disc to pre-load up to 27 scripts, then put the Apple keyboard on a remote tethered floor mount. I would control and switch CEEMAC animations with both of my big toes while simultaneously switching, mixing and colorizing synchronized layers of analog video with my hands.

At 1:24 is an example of live image processing, my blue colorized hand on a synthesizer keyboard with a negative luminance-keyed background generated by the Chromascope, an English-made analog video synthesizer that I specially modified to produce NTSC video.

At 3:00 is a short segment produced with Ross Hipley’s “Microflix” animation software for Commodore C64, rescanned with blue colorized video feedback trails. Most of the C64 graphics did not record well, causing the sections of apparently black screen. The layer of colorized feedback, like a cloud chamber tracing of the motion of radioacitve subatomic particles, reveals the beauty of the moving little "microflix" dots.

At 3:19 I launched a series of pure CEEMAC fire organ animations performed live to the music:

At 6:05 is another example of live image processing, this time colorizing a monochrome video image of the trees outside my bedroom window with synthetic patterns from the Chromascope:

At 7:22 is the output of one of my original CEEMAC scores in which I attempt to create texture and dimension using diffraction patterns and chroma shifting. In Apple II "Hi-Res" mode I was working with a 280px by 192px screen, 57 thousand pixels in all. A far cry from the 2.0736 million pixels we take for granted in standard 1080p video frames.

At 7:53, a doubly-mirrored color-shifted microcomputer graphic abstraction:

GM: Was it all mixed together live? Can you talk about the performance element of this?

DS: Yes, this is an edited collage of segments performed live to prerecorded music. The other element of the instrument that I didn’t discuss above was ¾” video[6] editing deck with fast, responsive buttons that let me perform live insert and assembly edits. I developed a stochastic layered video editing technique inspired by early videos on MTV.

The performance elements are better illustrated by two shows using this visual instrument. The first is Synthetic Pleasure (Plaisir Synthetique), a live performance at the Festival de La Rochelle in the south of France.

The second is Formula, my attempt to bring this dance/video art form to the USA.

In both cases I had taken pains to make my visual instrument portable, ergonomic, and rugged. In the second dance piece, "Formula", I have my assistant performing the visuals as I musically accompanied the dancers live on stage. It was important to make the instrument simple enough so that other people could quickly learn it and play it artistically.

GM: Did you produce the music?

DS: Yes. I've produced the music in all of my video art. "Sunflower Geranium" was a live 1983 electronic music performance with keyboardist Lauri Paisley, who played an ARP Omni. I'm playing the rhythmic chordal progression on a KORG PS-3100 feeding a tape-based stereo echo device. I play occasional melody lines with a Yamaha CS-60.

Today I am first and foremost a musician, an original classical keyboard concert soloist using electronic instruments. I have chosen to concentrate on music performance and have currently passed on my visual tools to other fine artists.

GM: So much of the power of the piece is the rhythm between the music and the visuals. It becomes almost overpowering. Can you talk about some of the objectives you had in combining the music and video?

DS: I was influenced by the emergence of music videos on MTV, which had just started. I was looking to capture the power of some of the pop and rock music videos I was watching using instrumental electronic music and a hybrid melding of analog and digital techniques. I was interested in taking it to the stage, live. I wasn't trying to produce the sophisticated polished work that I saw on TV. I wanted to squirt electrons with a hose, I wanted to feedback colorized video smoke the way Jimi Hendrix would feedback tones on his guitar.

GM: How much overlap was there between the electronic music scene and the scene around computer generated video art?

DS: They were always together, but very few people produced quality work in both art forms. I was rather isolated from other visual artists, and was mostly known as a musician.

GM: Who or what are some of your inspirations?

DS: I was influenced by Daniel Sandin's Image Processor and by Steve Rutt of the Rutt-Etra machine. They both influenced my designs and art. Ric Hornor always inspired me with his amazing video stills, and Carol Chiani kindly brought me into the community of NY SIGGRAPH.

GM: Where did you show your work?

As a video artist I was honored with a paid week-long residency at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, France sponsored by the French Ministry of Culture. I was encouraged by Jean-Claude Risset at IRCAM and Max Mathews at Bell Telephone Labs. In the mid-80s I did several live music video concerts at the New York Open Center that incorporated live theatrical image processing. Later I did a number of electronic music and computer graphic performances at NY SIGGRAPH. Through the good graces of Phillip Sanders I was included in the Internet Archive project which led to this interview.

GM: As technology has progressed, what would you like to see?

DS: I am looking to revive analog video synthesis. I believe that we could build analog video synthesizers at full 1080p resolution that would give unmatched live responsive HD animation power in the theater.

I would like to extend the aesthetics of current VJ practice. So much of the imagery projected on large screens in concert today seem psychedelic, druggy, intoxicating, and suitable only for rock, pop, or electronica. How could current VJ tools accompany classical, folk, world, or acoustic music? The art form needs to grow and mature.

[1] Chromaton 14 analog video synthesizer from BJA Systems. I was deeply involved with the Chromaton from 1977, when I first started working with the instrument, until 2001 when I placed it under the care of the talented visual artist Mr. David Egan of Audiovisualizers. I got to know the Chromaton 14 designer, Mr. Ralph Wenger, worked with the circuitry, and made hundreds of video stills (photographs).

[2] The Adwar Special Effects Keyer combined a bidirectional luminance keyer with a powerful colorizer, all done with analog circuitry. I used it with the Chromaton synthesizer for processing camera imagery.

[3] I used a Number Nine accelerator board that replaced the 1Mh 6502 processor with a 3.6Mhz processor. This made the Apple graphics, already quite fast, run 3.6 times faster. To put this in modern terms, imagine if you could add a board to your PC and run a 10Ghz processor to replace your 3Ghz processor.

[4] In 1981 the late Sam Adwar, maker of the Special Effects Keyer, made an NTSC genlock board for the Apple II+. There were only a few of these made, they were very expensive, and they completely replaced the standard Apple graphics with an output that could be genlocked to a standard NTSC sync signal.

[5] I used I used a the CEEMAC fire organ animation demonstration disc while doing this, which allowed me to pre-load 27 assembly language scripts and switch between them rapidly.

[6] Sony VO-2610 3/4" U-matic deck

Thanks for posting Sunflower Geranium and the interview. I was at the University of Illinois and produced a video piece the same year that has some of the same DNA. My piece was done with a camera/monitor feedback loop and some serious abuse of a Grass Valley video switcher. I pushed the switcher controls to just the point of instability to transorm what were otherwise cheesy wipe effects and filtered them through the feedback loop with chroma/luminance keying. Also on U-Matic 3/4" tape, I's love to get up to XFR STN, but have a somewhat aspect ratio challenged version at

https://vimeo.com/1686635

Barry

XFR STN runs through Sept 8 - if you have any plans to visit NYC, drop us a line!