Photo of Earth by the crew of Apollo 8. December 22, 1968

The central theme for this year’s Venice Biennale exhibition, curated by Massimiliano Gioni, comes from an obscure patented design for an encyclopedic palace by the self-taught Italian-American artist Marino Auriti. Envisioned as a 136-story building that would take over sixteen blocks of Washington, D.C., Auriti’s palace was to house all the available knowledge in the world. Titling the show "Il Palazzo Enciclopedico" after Auriti’s unrealized model, Gioni and his team selected an eclectic group of artists, psychologists, mystics and more whose work resonates with Auriti’s desire to create a total image of the world. In many ways, the exhibition can be seen as a response to the exhaustive overabundance of information available on the internet. As Gioni pointedly asks in his essay, "…what is the point of creating an image of the world when the world itself has become increasingly like an image?"

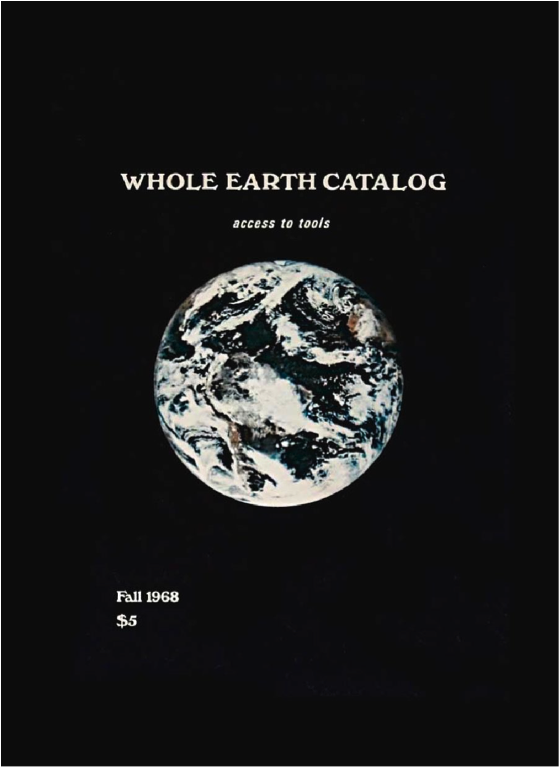

My experience of the Biennale was still fresh a week later when I visited "The Whole Earth: California and the Disappearance of the Outside" at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin. Curated by Diedrich Diedrichsen and Anselm Franke, the show investigated the influence of NASA’s first image of Earth from space, which appeared on the cover of the inaugural issue of the groundbreaking publication The Whole Earth Catalog. Organized as an experimental essay-as-exhibition divided into small vignettes, the show was a meditation on the elimination of boundaries and the sense of a universally shared, planetary human experience encapsulated by NASA’s image of the earth, which became a catalyst for a vast array of social, cultural and political movements and output beginning in the 1960s, especially in California.

After viewing both of these powerful and insightful exhibitions back to back, I’ve pondered the following: How can we represent the world in an image, and how can that image, in turn, inspire action? If Auriti’s fantasy of an encyclopedic palace is now a reality, where all knowledge is a click away, then what methods or strategies can we use to address the very networks that enable that exchange?

Venice: Il Palazzo Pazzo

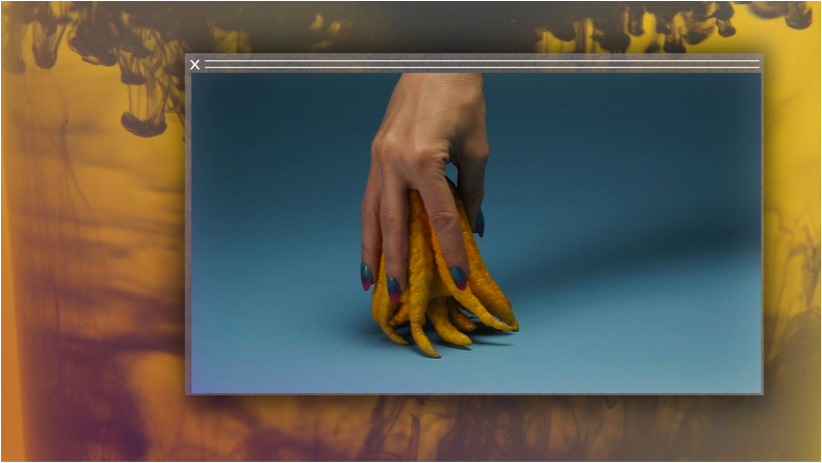

Housed in the first few rooms of the Arsenale, Camille Henrot’s Grosse Fatigue (2013) is a fast-paced thirteen-minute video that speeds through the evolution of all existence. Based on research conducted during a fellowship at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., the video weaves behind-the-scenes footage of the organization’s neatly catalogued collection and the scientists who oversee it with images shot within Henrot’s studio. Musician Akwetey Orraca-Tetteh raps over the video, and in sync with the montage, he rhythmically recounts the evolution of all life since the beginning of the universe, as well as the scientific fields that emerged to study them. The video illuminates how all life is connected, as well as the human race’s ongoing desire to understand the world. Grosse Fatigue won this year’s Silver Lion, and it’s easy to see why. Accelerated and exhilarating, the work captured the aspiration to see everything and be everywhere, all at once.

Camille Henrot, Grosse fatigue. Photo courtesy of the artist and Kamel Mennour Paris.

Further into the Arsenale, Mark Leckey’s The Universal Addressability of Dumb Things (2013) shared this sense of dizziness with Henrot's piece, but spiraled in a new direction. The work, which is a snapshot of his larger exhibition of the same title, explores how our current technological capabilities have yielded inert objects—things—an eerie sense of animism. Wielding tropes of museum exhibition display in a playful and quirky manner, Leckey’s installation presents the inner lives of things. When our toasters begin to speak back to us, it moves the desire to see "everything and everywhere" expressed in Henrot’s work (and that of many other artists in the exhibition) away from an exclusively anthropocentric perspective.

Leckey’s work foretold a strange world to come, but with a good dose of humor and lightheartedness. The future reflected in Ryan Trecartin and Lizzie Fitch’s installation Not Yet Titled (2013) in the Arsenale was even stranger and more foreboding. The work ventured deep into the American psyche, conjuring celebrity culture, narcissistic consumerism and the raw voyeurism of reality TV. Warped and bizarre, the installation felt like a time capsule sent backwards from a schizophrenic future set in the Midwest. Trecartin’s work is always an exaggeration, an amplification, of what is already existent in popular culture. I believe this quality is the central allure in his practice, and it is also what makes his work so unnerving; the madness portrayed on screen is both over the top and familiar.

Ryan Trecartin and Lizzie Fitch, Not yet titled, 2013

Photo by Francesco Galli

Courtesy by la Biennale di Venezia

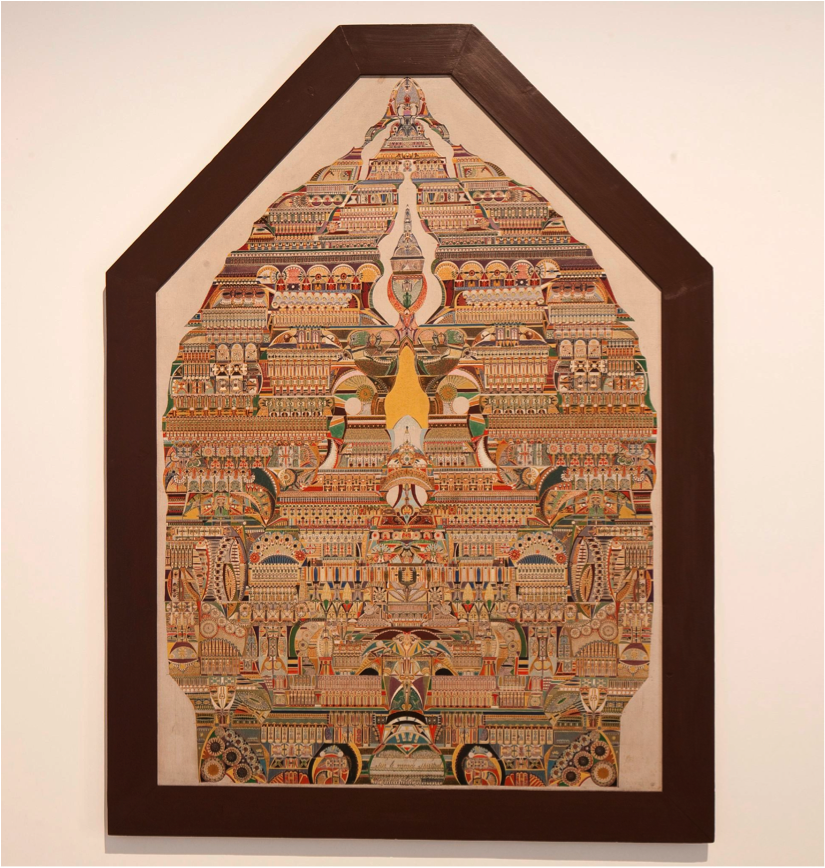

Indeed, madness was one of the strongest themes within the entire exhibition. Cataloging the world is an impossible venture, often with insanity or mystical belief as the underlying impulse, if not the result. Gioni delicately addressed mental illness and spirituality without an air of exploitation. Lesser known, often self-taught, artists such as Augustin Lesage, Hilma af Klint and Emma Kunz dotted the exhibition, especially in the Giardini section. Their personal stories were as intriguing as the art itself, such as the voices that instructed Augustin Lesage to paint while he was at work in a mineshaft or Emma Kunz’s integration of drawing into her healing rituals. These artists call on other forces to navigate and access a total that is beyond comprehension, that is unthinkable.

Augustin Lesage, Composition symbolique sur le monde spiritual, 1925

Photo by Francesco Galli, Courtesy by la Biennale di Venezia

"You Can Only See About Half the Earth at Any Given Time"

The artists in "Il Palazzo Enciclopedico" point to the impossibility of producing an image of the world in all its complexity. The exhibition The Whole Earth: California and the Disappearance of the Outside" follows a related trajectory by focusing more narrowly on the effect of one image of the world, NASA’s photo of the earth from the 1968 Apollo 8 mission. The first ever photo of the planet from space allowed the ungraspable—one world—to make sense to many during the potent social and political upheaval of the 1960s. As curator Anselm Franke explains in his essay, the photo "...appears to transcend all frames, borders and preconfigured notions of order; dissolving them in an oceanic vertigo." The subtitle "Disappearance of the Outside" refers to this reconfigured perspective, which is boundless and seemingly outside history. That position sparked the countercultural experimentation and output of the late 1960s, whose ideals eventually became interwoven with the boundlessness of networked, neoliberalist capitalism. Like Adam Curtis’s documentary film All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace (2011), as well as Fred Turner’s 2006 book From Counterculture to Cyberculture, the exhibition follows the connection between the 1960s California counterculture and neoliberalism, or what others have called the Californian Ideology. Displays fanned out in various formations around the exhibition hall that examined subthemes like the environmentalist movement and LSD. Artworks from the period, such as the psychedelic abstract films of Jordan Belson, Andy Warhol’s Outer and Inner Space (1965) and Robert Rauschenberg’s poster Earth Day (1970) were paired alongside posters and ephemera. More contemporary works from 2000 onwards by artists like Sharon Lockhart, the Otolith Group, Angela Bulloch and Philipp Lachenmann were interspersed throughout the exhibition, some suspended by metal wire from the ceiling. For these works, the wall text was attached to the floor beneath them, communicating to the viewer that their function in the show was slightly different than say, a copy of Mother Earth News. I wouldn’t describe the exhibition as a historical survey exactly, rather, the show felt like an assemblage of notes towards a thesis with several nested subcategories.

Stewart Brand (Ed.), Whole Earth Catalog Fall 1968 (Cover)

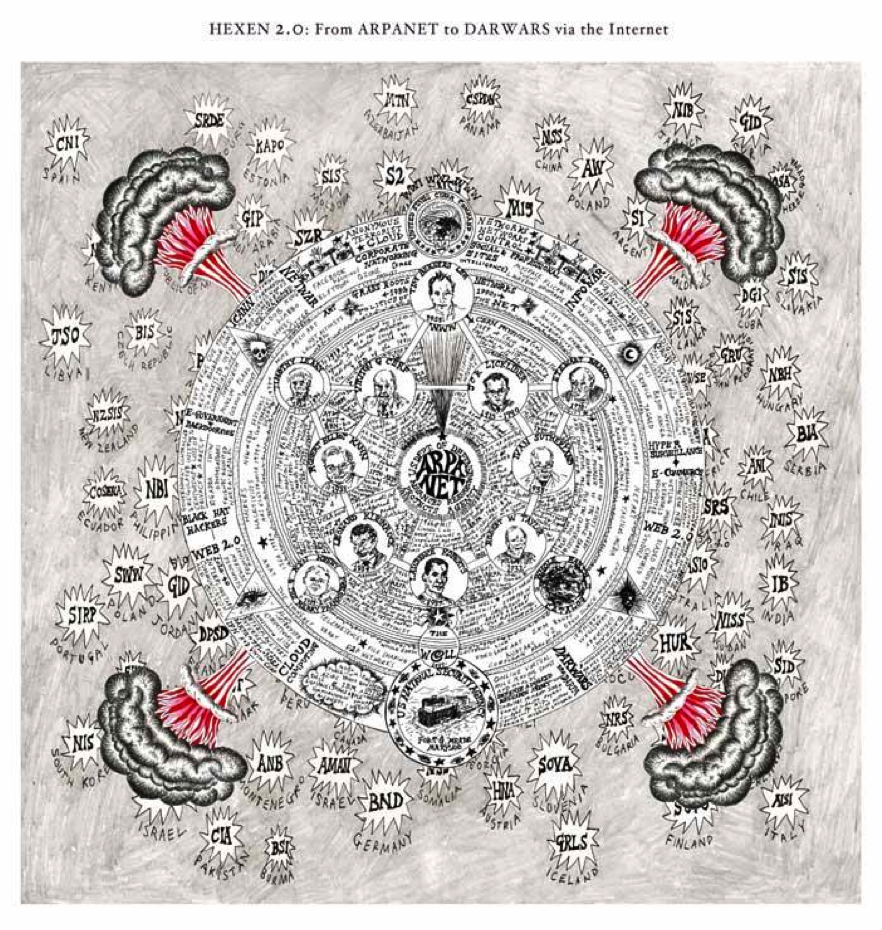

Among the most compelling inclusions in the show were a number of works from Suzanne Treister’s series of drawings, HEXEN 2.0 (2009-2011). The diagrams from the series, such as HEXEN 2.0/Diagrams/From ARPANET to DARWARS via the Internet, were attempts to map out the historical connections among cybernetics, military technology, the Internet and social media. Her ornately detailed drawings looked like pages from a conspiracy theorist’s notebook, replete with bubbles and arrows and incredibly small written text.

Treister’s attempt to visualize what she terms "new systems of societal manipulation towards a control society" reminded me of a question posed recently in Alexander Galloway’s book Interface Effect. In an essay entitled "Are Some Things Unrepresentable?" he makes the claim that an adequate visualization of a control society has not yet happened yet, and that there’s an inability to represent the power of networks, algorithms, information and data. This is attributed to the functional aspect of data itself, which he argues lacks a visual form. When it is visualized, it always looks the same: as a flow chart, a cloud, etc. (Surely, in support of this statement, Treister’s diagrams looked quite similar to the information map works by Bureau d’Etudes referenced in Galloway’s essay. Both artists strive to map a control society, with practically the same result.)

If the network is the preeminent means by which power is wielded today, and if it remains unrepresentable, then how does one build a responsive poetics? In other words, how does one build a counter-aesthetics to the algorithmic logic of the network, with the knowledge that representation itself needs to be reconsidered within that framework? This is the dilemma presented by Galloway, and it’s an urgent question. "The Whole Earth: California and the Disappearance of the Outside" illustrated how an image of the world was instructive in radically shifting a paradigm, for better and for worse. On the other side, the works displayed in Gioni’s Il Palazzo Enciclopedico express the immensity of information overload produced by the network, without ever motioning towards an image of the network itself. So, what to do? How can we depict networks, the central driving force in our world today? Or is it even possible? Can images of worlds still inspire new worlds, or are we at a dead end?

Suzanne Treister, HEXEN 2.0/Diagrams/From ARPANET to DARWARS via the Internet, 2009-2011

Copyright the artist, Courtesy Annely Juda Fine Art

Disclosure note: Massimilano Gioni is Associate Director and Director of Exhibitions of the New Museum, Rhizome's affiliate organization.

Update: an earlier version of this article incorrectly identified the voice in Grosse Fatigue as that of Joakim Bouaziz. The narrator was Akwetey Orraca-Tetteh; Bouaziz composed the score.

DIABOLICA: THE VATICAN AND THE VENICE BIENNALE 2013

http://rhizome.org/announce/events/59702/view/