Artwork from ASCII Art Dictionary (possibly 1999).

This is the second in a three-part series to be published on Rhizome. The first part, exploring the history of the emoticon, can be found here. The final installment (forthcoming) will explore the history of the emoji.

1.

Following in the footsteps of Baudelaire—and paving the way for the Surrealists and the French New Wave—early 20th-century artist Guillaume Apollinaire cultivated a cerebral taste for the most sensational elements of modern life. A poet by calling and a publicist by trade, Apollinaire seized on the outrageous whether he found it in the avant-garde (he coined the term "Cubism" in praise of early paintings by Braque and Picasso) or mass culture (he called the serialized tales of fictional super-villain Fantômas "one of the richest works that exist.") Apollinaire’s poetry fed on the chaos of Paris in the early 1900s. Take this representative passage from 1909’s "Zone":

You read handbills, catalogues, posters that shout out loud:

Here’s this morning’s poetry, and for prose you’ve

got the newspapers,

Sixpenny detective novels full of cop stories,

Biographies of big shots, a thousand different

titles,

Lettering on billboards and walls,

Doorplates and posters squawk like parrots.

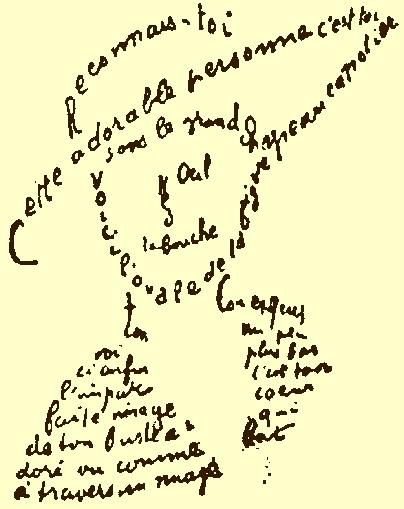

Apollinaire’s 1918 book Calligrammes delved further into its source material, imitating its typographic forms to create pictograms in which the text echoes the image. For obvious reasons, the calligrammes are notoriously hard to translate, but to give you some idea: the following picture of a woman wearing a hat is made up of a text about a woman wearing a hat:

Guillaume Apollinaire, Extrait du "Poème de 9 fevrier" (1915).

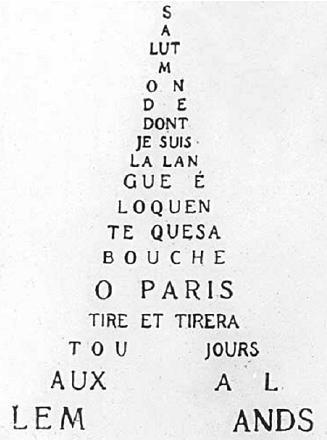

In this one, the Eiffel Tower addresses the reader:

Guillaume Apollinaire, "Salut monde dont je suis la langue éloquente que sa bouche Ô Paris tire et tirera toujours aux allemands" (Published in Calligrammes, 1918).

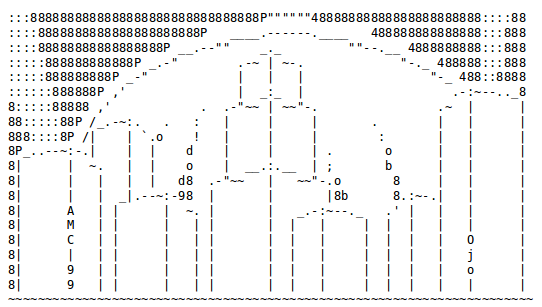

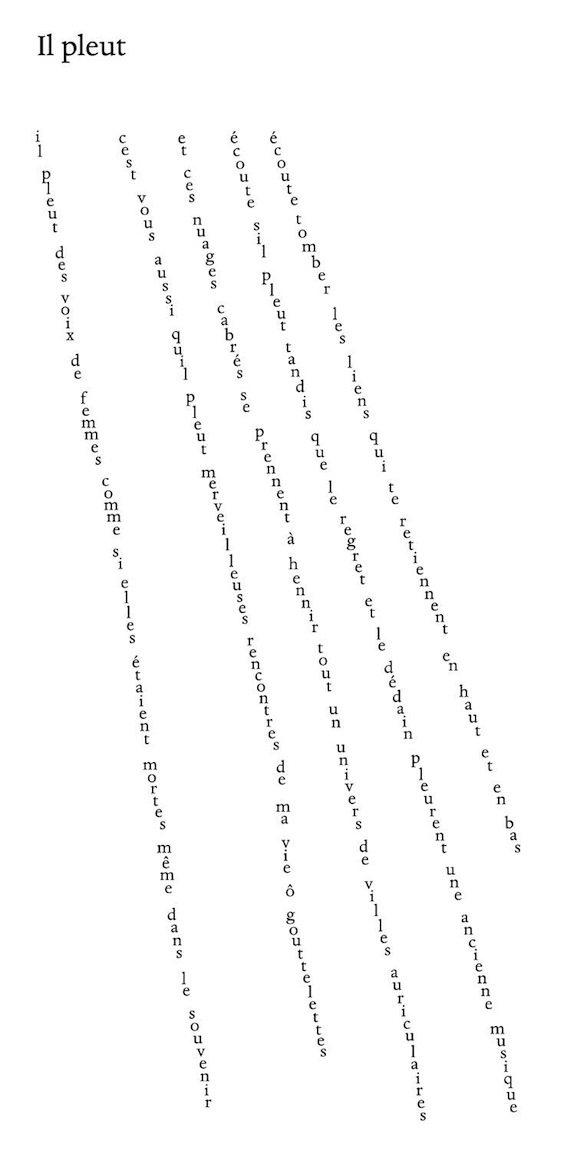

In "Il Pleut," Apollinaire rendered the rain as cascading letters, suggesting the interplay of natural phenomena with his beloved billboards and street signs.

Guillaume Apollinaire, "Il Pleut" (Published in Calligrammes, 1918).

Glossing Calligrammes in a letter to a friend, Apollinaire wrote that they were "typographic precision made in a period when typography is winding up its career brilliantly, at the dawn of the new means of representation, cinema and the phonograph." If Apollinaire was correct that typography was witnessing a brilliant period, he was wrong that it was winding up its career.

As for cinema and the phonograph...

2.

Handbills, catalogues, posters that shout, and posters that "squawk like parrots" all betray a modern impulse that found its fullest expression in the full-page Sunday comics, which freely layered text and image while juggling—whoosh! splat!—their connotative and denotative values.

Early picture shows—nephews of the Sunday comics—employed narrators who stood in front of the screen and talked to the audience, explaining what was going on or making jokes. The movie theater was marketed as an oasis from the chaos of urban life, but as screens got cheaper and more portable, moving pictures took their logical place in the city, which was everywhere. People could offer explanations or crack jokes themselves.

The two categories of representation that Apollinaire defined—“typography” on the one hand; “cinema and the phonograph” on the other—collapsed into each other on the World Wide Web, which hyperbolized the vernacular of the modern city.

It’s no accident that today’s Web-romantics embrace the same aesthetic and social agenda as a previous era’s city-romantics. Aesthetically: speed; sensation; the blending together or overturning of traditional forms; one-upmanship; creative trickery. Socially: pluralism; agonism; the wisdom of crowds; justice in numbers and witnesses.

All of which could be summarized as: the sheer nearness of everything to everything else.

3.

Early interfaces for the Internet offered only official characters from the American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII).

Developed and codified in the early 1960s through an obscure and prolonged collaboration between corporate technologists and government bureaucrats, ASCII (pronounced "ass-key") is based on the English alphabet, and comprises the characters we now recognize from contemporary computer keyboards.

Some of the most interesting artifacts of the early Web were termed "ASCII art," and consisted of pictograms and other visual patterns made from ASCII characters. The emoticon is an early, and relatively simple, example.

ASCII art was an aesthetic foreshadowing of what would become the culture’s social vision for the Web: the Internet would be the paradisaical city of our dreams; the ultimate melting pot; the high-tech global village we’d been promised. Home to a natural, nearly-inevitable democratic virtue, it would be a place where your identity could merge with the crowd, and even be shed entirely; and a super-speed air-tram could transport you from uptown to down in the amount of time it takes to register for a gonzo pornography subscription service.

4.

Just as the fresco thrived in the chapels and mansions of Early Modern Europe, the golden age of ASCII art took place on Usenet in the 1980s. Usenet improved the functionality and expanded the scope of bulletin board systems; the trick was abrogating the need for a local server/hub, and instead transferring information just from one to server to the next, and the next, and back and forth and so on—similar to modern day peer-to-peer file-sharing programs. Usenet took advantage of the Internet by creating an interface that was cognate with the Internet’s structuring conceit: decentralization, an important idea in the US in the 1980s.

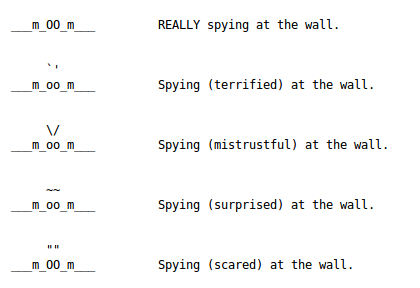

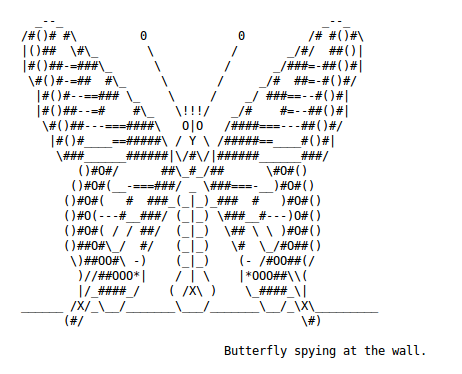

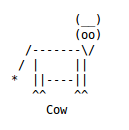

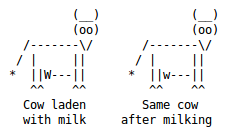

In addition to the emoticon, the foundational works of ASCII art were "Spying at the Wall" and "Silly Cows." "Wall" and “Cows" were, like the emoticon, iterative and multi-authored, and the three works can be seen as the earliest known "Internet memes."

The purportedly first version of "Spying at the Wall" was composed of two underscores, an "m," another underscore, two "o"s, another underscore, another "m," and two more underscores. It conjures a little peeping Tom, wide-eyed, hands braced; a rapt but inscrutable gaze traveling endlessly through a burgeoning World Wide Web, peering over "the wall":

![]()

Initial variations sought only to add emotional complexity.

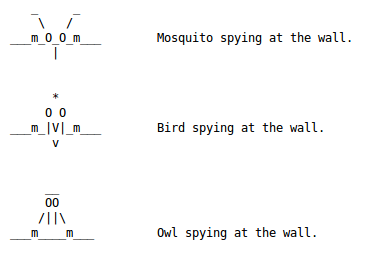

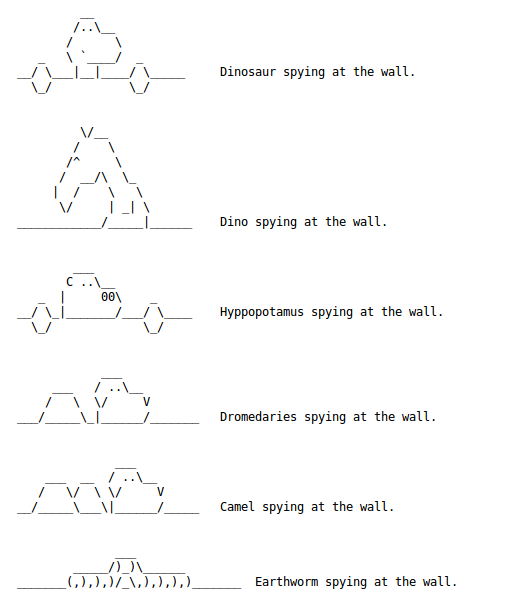

ASCII art techniques developed quickly. The kind of line drawing seen above developed into “Spying” animals such as these:

But in other animal variations, line drawing took a different shape:

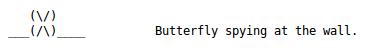

Developments in the genre can be understood by comparing this simpler, presumably earlier, butterfly:

With this more elaborate, presumably later version:

In the above image, the wall serves little purpose, except to tell us that the butterfly is in repose, not flight. The idea of 'spying' remains visually underdeveloped.

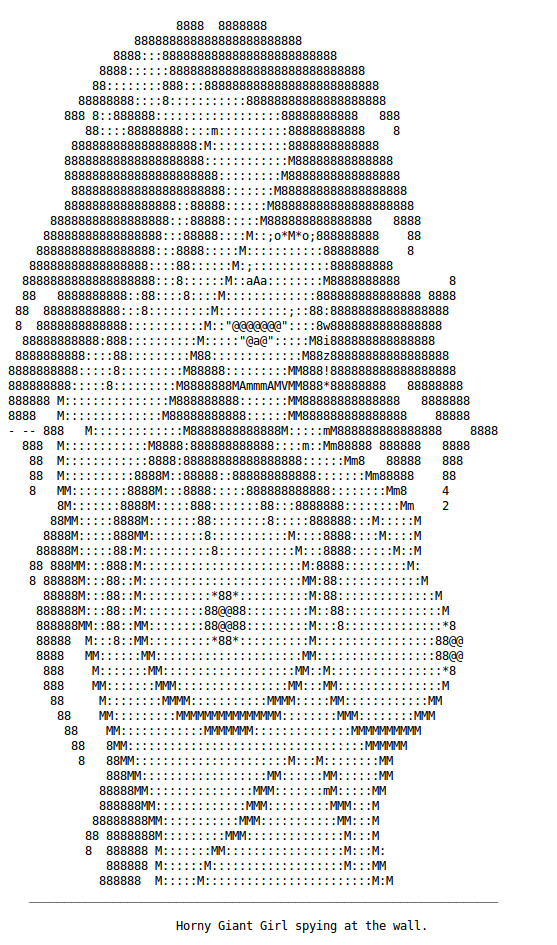

In “Horny giant girl spying at the wall,” neither the conceit of the wall nor the spying seem to serve any purpose whatsoever, except to bait the audience into giving themselves over to another fixation entirely.

The original iteration of “Silly Cows” was more complex, and so its variations were less free-form.

Though the premise, like “Wall,” gave rise to an interest in anatomy:

5.

ASCII artists took the form in many different directions, but the most common model they claimed for themselves was the graffiti artist. So there came to be “Oldskool” and “Newskool” ASCII art, neither named in reference to the date of its development, but rather in reference to a vibe; and so ASCII artists, somewhat vertiginously, became obsessed with rendering words out of and within images.

For example, this undated scene, by an artist calling her or himself “ejm,” not only pictures the weather but remarks on it:

This more famous piece from 2007, by artist Roy, was done in a Newskool style and, somewhat ominously, renders the phrase “closed society” mostly out of dollar signs:

Roy, Closed Society (2007). Screen capture of ASCII artwork.

6.

The introduction of graphical interfaces for the Internet put an end to the high period of ASCII art. The most common graphical interfaces for the Internet are called "Web browsers." These interfaces interpret many different character sets and file formats and establish a sense of continuity for users engaged in sending and receiving billions of fractured electronic signals around the globe.

The first commercial Web browser, Mosaic, was released in 1993. The first video live-streamed on the Web was a June 24, 1993 performance by SoCal garage rock group Severe Tire Damage, whose bassist at the time was the chief scientist at Xerox, a company in the middle of developing live-streaming software.

The following years saw several different companies—Windows, Apple, and RealNetworks, mostly—frantically trying to codify Internet video and image formatting.

These years saw two other, related developments: the creep of Internet culture into popular culture at large in films like Hackers and The Net (both 1995), and the first recognizable net-native avant-garde art movement.

Mid-90s artists such as Vuk Cosic, JODI, and Alexei Shulgin were grouped under the term “net.art,” and while the work under this label was various, all of it shared a desire to disrupt the system of continuity that had been introduced by Web browsers and codified by corporate Web design.

Art collective JODI, for instance, made websites that would pop open so many windows that browsers would malfunction and close down. The strategy was called “browser crashing.”

Throughout the 90s, net.artist Vuk Cosic worked primarily with ASCII characters. His most famous work is "ASCII History of Moving Images," from 1998.

The series renders iconic scenes from the history of cinema and television in ASCII characters. With selections from Eisenstein, Hitchcock, and Antonioni, the series climaxes with Cosic's most brilliant choice. Nowhere else in Cosic's work is his representational mode so perfectly at odds with the aim of the original work. And it was eerily apposite for Cosic to finish his series by transforming an early representation of an act whose depiction would become central to so much of our Internet culture.

User FILMDATA01 updated the artwork to YouTube in 2008—Cosic's ASCII rendering of a scene from the 1972 film Deep Throat.

The look of Cosic's “ASCII History of Moving Images” was borrowed by the Wachowski brothers, who, somewhat poignantly, used it in their 1999 film The Matrix to imagine what a simulated city might look like to someone who could see through its illusions.

7.

ASCII art only ever flourished as a truly popular genre in the form of emoticons, which in the 2000s were eclipsed by the Japanese Corporation SoftBank's supplemental character set of “Emoji.” (Emojis will be the subject of the next and final installment of this series of essays.)

ASCII art persists now mostly as a connoisseur's medium.

The majority of extant ASCII artworks remain undated, but this rendering of Apollinaire's “Il Pleut” was probably created after artists in the medium started historicizing themselves, maybe some time around 1998, the year the “Dancing Baby” became the first Internet meme to attract the attention of corporate media, appearing on news stories and making its way into Fox's Ally McBeal.

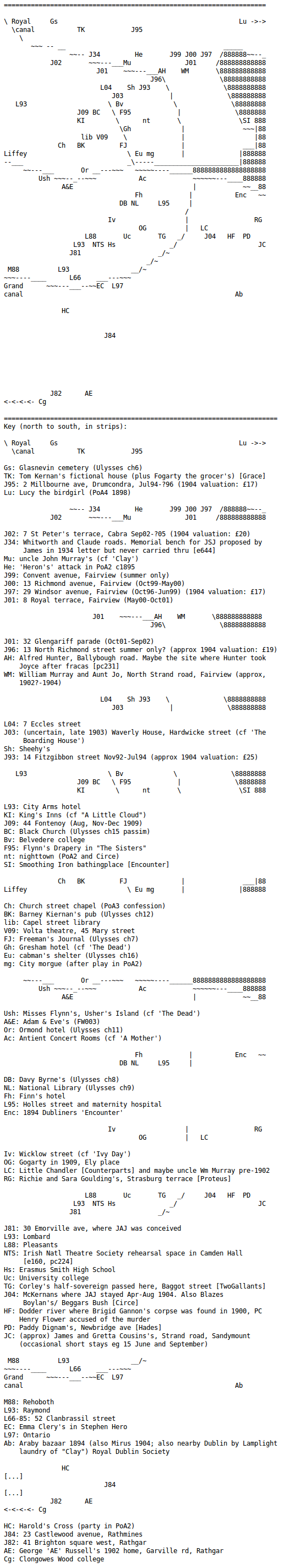

Personally, my favorite piece of ASCII art, also undated, is a map of Leopold Bloom's path through Dublin in James Joyce's Ulysses. A painstaking labor of love, and a work that knots together its form and subject to make visible the conditions of its own historical occurrence, the image recalls the dream of a city knit together by people’s stories and desires—a world wide web that never came to fruition.

In general, a really interesting overview - thanks for posting about ASCII art. It might be nice to consider Dick Higgins' book Pattern Poetry for some more deep historical references.

Indeed interesting, but I'm missing De Stijl, Dada,… in the historical context…

Not only Dick Higgins' book Pattern Poetry, but also the following books could be of interest to go more into the historical context and the DNA of these poetic forms (the ones with a star* are essentials):

Willard BOHN, Modern Visual Poetry, Newark-Londen, 2001

*Willard BOHN, Reading Visual Poetry, Lanham-Plymouth, 2010

*Dmitry BULATOV (ed.), A Point of View: Visual Poetry, The 90s. An Anthology, Kaliningrad-Koningsberg, 1998, 592p

*Klaus Peter DENCKER, Optische Poesie. Von den prähistorischen Schriftzeichen bis zu den digitalen Experimenten der Gegenwart, 2011

*Johanna DRUCKER, “Experimental, Visual and Concrete Poetry: A Note on Historical Context and Basic Concepts.”, Avant-garde: critical studies, 10, 1996, p. 39-64.

Marcel DUCHAMP, The Writings of Marcel Duchamp. edited by Michel Sanouillet and Elmer Peterson, New York, 1973, p196

Eugène GOMRINGER, “Concrete Poetry”, translated by I. MONTJOYE SINOR & M. ELLEN SOLT, in: Ubuweb Papers, (online), http://www.ubu.com/papers/, 2.3.2005, http://www.ubu.com/papers/gomringer02.html, last consulted on 26.4.2012

Jamie HILDER, Designed Words for a Designed World: the International Concrete Poetry Movement, 1955-1971, Vancouver, 2010, 237p

Karl KEMPTON, VISUAL POETRY: A Brief History of Ancestral Roots and Modern Traditions, 2005, Oceano, (online) http://glia.ca/conu/digitalPoetics/, last consulted on 8.5.2012

Jerrold LEVINSON, “The Irreducible Historicality of the Concept of Art”, British Journal of Aesthetics, 42/4, 2002 , p. 367- 379

Philip MEERSMAN, “Visuele poëzie”: een semiosfeer met eigen logica en eigen onderzoeksveld., unpublished, Brussel, 2012

Tatiana NAZARENKO, “Re-Thinking the Value of the Linguistic and Non-Linguistic Sign: Russian Visual Poetry without Verbal Components”, SEEJ, 47/3 (2003), p. 393-422.

Humphrey OTTENHOFF, De letter te lijf. Beeldvorming van concrete en visuele poëzie in Nederland en Vlaanderen, Groningen, 2005, 329p.

Claudio PARMIGGIANI (ed.), Alfabeto in sogno. Dal carme figurato alla poesia concreta, Milaan, 2002, 466p.

Anna Christina RIBEIRO, “Intending to Repeat: A Definition of Poetry”, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 65/2 (2007), p. 189-201.

Karel TEN HAAF, Zieteratuur. Concrete en visuele poëzie uit Nederland en Vlaanderen., Groningen, 2010, 136p.

Susanne VAN DEN HEUVEL, Van klank naar beeld en vice versa, over grafische muzieknotatie en ‘muzikale’ typografie, Breda 2009

Nico VASSILAKIS & Crag HILL (eds.), The Last Vispo Anthology: Visual Poetry 1998-2008, Seattle, 2012, p.336

Helen WHITE, Visual Poetry in De Tafelronde, 1965-1979, unpublished, Ghent, 2004

…

I did my bachelorpaper and am writing a master paper on visual poetry… so if you need more info… let me know

hi,my master paper is about emoji and concrete poetry.

philip - i'd love to talk more! i agree, there are connections to dada, concrete poetry/visual poetry for sure. i also think there are connections to algorithmic writing like oulipo. i've done some research to try to pull these things together a bit. i can share the paper i wrote with GOTO80 last year if you're interested.

also, was having a conversation last week about some of this and found on Vuk Cosic's site: http://www.ljudmila.org/~vuk/ascii/vuk_eng.htm

which i think also draws some similar conclusions.

[_] [_] [_] [_]

Awesome thread and thanks for the list of writing on the subject to check out, Philip

"Spying at the wall" was likely inspired by the WWII-era Kilroy was here graffiti doodle/meme.

I'm enjoying this series, especially the comparisons to calligrammes, and am looking forward to the third installment.

One small correction: The "Closed Society" image by Roy of SAC was created October 24, 1997 and published worldwide in an artpack, SAC1297B.ZIP, in December of the same year.

source: http://sixteencolors.net/pack/sac1297b

// (( || ))

Not that anyone's still paying attention to this thread, but I keep referring to it, so it's still useful to drop this prior art from 1883 if only for my own sake:

http://bklyn.newspapers.com/image/50431380/

These are ads from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 19, 1883. It appears as if it was common practice to arrange characters of smaller fonts into larger characters in the absence of a larger font set. Obviously these aren't pictograms, but the (presumably) pervasive nature of this practice seems like an interesting part of this story, predating even the 1893 Illustrated Phonographic World article defending "Typewriter Art":

http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2014/01/the-lost-ancestors-of-ascii-art/283445/