(This is the first in a three-part sequence to be published on Rhizome.)

“A new word is like a fresh seed sewn on the ground of the discussion.” -- L. Wittgenstein, Culture and Value (trans. Peter Winch)

“If writers wrote as carelessly as some people talk, then adhasdh asdglaseuyt[bn[ pasdlgkhasdfasdf.” -- L. Snicket, A Series of Unfortunate Events

By September of 1982, the Computer Science Bulletin Board System at Carnegie Mellon University was a social hotspot, at least for certain science professors and tech geeks. Bulletin Board Systems (BBSs or bboards) pre-date the Web as such; they allowed users to dial into a local hub, through which they could send messages to and receive messages from other machines dialed into the same hub. Dating back to 1978, bboards didn’t get popular until the 80s, following the 1981 release of Hayes Communications’ cheap and effective Smartmodem, which made hosting bboards more affordable and using them less arduous, if still not entirely intuitive.

Bulletin Board Systems became popular on many college campuses, absorbing some of the discourse of the hallway and the common room, and attracting those people—like physicists and Heideggerians—predisposed to adopt hobbies with steep learning curves.

Bboards were not only localized but divided into discussion groups, each developing their own jargons, rituals, and codes of conduct. The Computer Science BBS at Carnegie Mellon was used, inter alia, for complaints about and discussions of school laboratories, the proposing of elaborate hypothetical experiments, and joking around at an advanced level about atoms and alkaloids.

Prankish posts on the CMU CS discussion group were generally taken in stride. But because threads could be hard to track—with abruptly dropped topics; shifts and stutters—context could quickly be lost and readers confused.

At around noon on September 16th, 1982, and in response to a similar scenario involving pigeons, Neil Swartz posted the following hypothetical situation to the CMU CS BBS:

There is a lit candle in an elevator mounted on a bracket attached to the middle of one wall (say, 2" from the wall). A drop of mercury is on the floor. The cable snaps and the elevator falls. What happens to the candle and the mercury?

About five hours later, and after a number of unrelated messages, Howard Gayle wrote a message with the heading, “WARNING!”:

Because of a recent physics experiment, the leftmost elevator has been contaminated with mercury. There is also some slight fire damage. Decontamination should be complete by 08:00 Friday.

Rudy Nedved tried to prevent mass hysteria:

The previous bboard message about mercury is related to the comment by Neil Swartz about Physics experiments. It is not an actual problem.

Last year parts of Doherty Hall were closed off because of spilled mercury. My high school closed down a lab because of a dropped bottle of mercury.

My apology for spoiling the joke but people were upset and yelling fire in a crowded theatre is bad news....so are jokes on day old comments.

Neil Swartz, who posed the original question, later replied:

Apparently there has been some confusion about elevators and such. After talking to Rudy, I have discovered that there is no mercury spill in any of the Wean hall elevators.

Many people seem to have taken the notice about the physics department seriously.

Maybe we should adopt a convention of putting a star (*) in the subject field of any notice which is to be taken as a joke.

Joseph Ginder liked the idea, but had his own take:

I believe that the joke character should be % rather than *.

To which Anthony Stentz added:

How about using * for good jokes and % for bad jokes? We could even use *% for jokes that are so bad, they're funny.

“No, no, no!,” wrote Keith Wright:

Surely everyone will agree that "&" is the funniest character on the keyboard. It looks funny (like a jolly fat man in convulsions of laughter). It sounds funny (say it loud and fast three times). I just know if I could get my nose into the vacuum of the CRT it would even smell funny!

On September 17th, user Leonard Hamey proposed, with his own somewhat elaborate justifications, that a pictogram should be used to represent joking, as opposed to a more basic cipher:

I think that the joke character should be the sequence {#} because it looks like two lips with teeth showing between them. This is the expected result if someone actually laughs their head off. An obvious abbreviation of this sequence would be the hash character itself (which can also be read as the sharp character and suggests a quality which may be lacking in those too obtuse to appreciate the joke.)

Hamey’s idea must have caught the eye of CMU professor Scott Fahlman, because two days later, in a rather brief missive, Fahlman offered his own pictogram:

I propose that the following character sequence for joke markers:

:-)

Read it sideways.

Actually, it is probably more economical to mark things that are NOT jokes, given current trends. For this, use

:-(

Scott Fahlman’s suggestion could have—like Niel Swartz’s, Joseph Ginder’s, Anthony Stentz’s, Keith Wright’s, and Leonard Hamey’s—been quickly forgotten. But Fahlman’s smiley garnered a peculiar reaction: people started using it as a specific basis for minor variations. Within two days, the CMU CS bboard had not just:

:-)

and:

:-(

but:

:-o

and:

:-|

A little over a month after Fahlman’s post, James Morris of Rutgers University posted a message to their WorkS BBS with the heading, “Communications Breakthrough”:

Because you can't see the person who is sending you electronic mail, you are sometimes uncertain whether they are serious or joking. Recently, Scott Fahlman at CMU devised a scheme for annotating one's messages to overcome this problem. If you turn your head sideways to look at the three characters :-) they look sort of like a smiling face. Thus, if someone sends you a message that says "Have you stopped beating your wife?:-)" you know they are joking. If they say "I need to talk to you :-(", be prepared for trouble. Since Scott's original proposal, many further symbols have been proposed here:

(:-) for messages dealing with bicycle helmets

@= for messages dealing with nuclear war

<:-) for dumb questions

oo for somebody's head-lights are on messages

o>-<|= for messages of interest to women

~= a candle, to annotate flaming messages

Fahlman’s design had caught on; the reaction it provoked proved significant.

Longform writing modulates affect through symmetries and variations in word choice and sentence structure; set ups and punch lines; recursive metaphorical conceits; ellipses; and all the other fiction workshop buzzwords that constitute what we call a piece of writing’s “tone of voice.”

The conjuring of a voice where there is only actually just a bunch of static text is a huge part of the Magick of good writing. But much of the written word is not trying to be good, in this sense.

The CMU CS bboard could have dictated that all jokes be written with the skill for compression, mimicry, and understatement of James Thurber or S.J. Perelman, but this would have likely betrayed this bboard’s social function, which was to facilitate amusing or pragmatic and low-investment communication among people who seem, for the most part, not to have been humanities majors.

The question of what symbol or symbols can or should substitute for tone of voice was considerably worked over by the CMU CS BBS. What distinguishes Falhman’s from the previous suggestions is that it simultaneously accented the lyrical expressiveness of the word-substitute and added an element of modular variability, two of the most important qualities of the more involved longer-form writing the smiley was intended to obviate.

Leonard Hamey’s Cheshire parenthetical— {#} — was similar, but its expressiveness is mostly fixed, because a keyboard offers few substitutes for the objects being signified. Teeth, which dominate Hamey’s design, are, anyway, not all that expressive in and of themselves; the varying shapes of mouths and eyes, on the other hand, seem to tap directly into our DNA. And a keyboard offers many substitutes--possibly because, actually, our desire to read and read into faces and eyes and mouths is so hardwired into our motherboards that we tend to read them into everything: power outlets, planets, randomly distributed paint on a canvas; slashes, commas, and dollar signs.

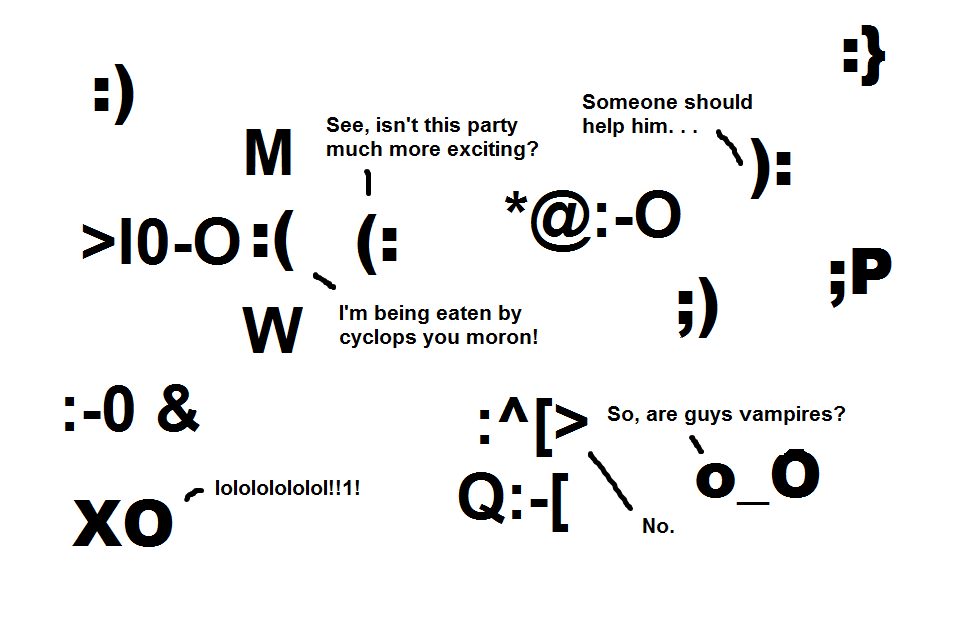

In 1993, 11 years after Falhman’s post, the emoticon got its own novelty dictionary with over 650 entries, although that number is slightly less impressive when you realize that many arrangements are listed multiple times. For example, this:

: - = )

is filed under both “Older smiling man with mustache” and “Adolf Hitler.”

The dictionary entries range from the evocative:

: - 9

licking its lips

to the gnomic:

: ]

Gleep: a friendly midget smiley who will gladly be your friend

and include self-reflexive sequences that exist only to make sport of the form:

:_)

nose sliding off face

and virtuoso offerings:

o0 : - ) ***

Santa Claus

The same year The Smiley Dictionary was released, the new slang received another signal of cultural ascendancy: a hit-piece in the New Republic. Neal Stephenson, a science-fiction author, obsessive autodidact, and sometimes-futurist, began an editorial on the phenomenon:

The online world has its own cliches and truisms, none so haggard as the belief that reliable written communication is impossible without frequent use of emoticons, better known as the "smileys."

Comparing smileys to spin doctors and Vegas rimshots, Stephenson argued--not entirely correctly--that people had written “for thousands of years without strewing crudely fashioned ideograms across their parchments.”

Not only that, but Stephenson saw emoticons as a symbol of the historical amnesia that was gutting the entirety of Western Civilization. The emoticon-users clearly believed they had “nothing useful to learn from Dickens or Hemingway, and that time spent reading old books might be better spent coming up with new emoticons.”

Stephenson imagines emoticon-wielding troglodytes offering strange arguments of their own, e.g., that “words on a computer screen are different from words on paper”; and that “since many messages are tossed off extemporaneously, the medium has more in common with talking than writing, hence the need for emoticons.” Stephenson was ready to rebut all this and more: “What these people are engaged in is, in fact, nothing other than plain old writing and reading.”

In 2003, Stephenson announced an about-face on the matter of emoticons, perhaps after realizing that following Cuneiform script, Egyptian hieroglyphs, papyrus, reeds, quills, Prüfening inscription, letter tiles, screw presses, movable type, Dvorak, Qwerty, dictaphones, telegrams, post-it notes---choose your own additions-- there has never been anything that could accurately be called “plain old writing and reading.”

If you prefer the diction, style, typography, mode of distribution—or anything else--of a specific culture or sub-culture for the 20 or 200 years leading up to whatever linguistic development offends you, say so, but you’ll have to actually describe what it is about the language practices of that specific place and period you find preferable--if you want not to look like an a-historical dum-dum or ignorant cultural chauvinist.

The problem with Stephenson’s retraction—which he posted to his blog--was that he replaced one fallacious argument with another. Confessing that he now considered his original article wrong in both tone and content, Stephenson explained that while he’d once thought that all writing should tend toward a “Platonic ideal,” he had since “become more interested in the way that people (including myself) actually do write, and have stopped worrying so much about how they ought to write.” The opposition here suggests that any polemic about the use or mis-use of language is philosophical fancy on the level of Platonic Idealism.

Each position neatly absolves everyone of the responsibility of making an actually substantive value judgment, by either assuming a development is unlicensed because it betrays the past or licensed because it’s born out of the pressures of the present. This is typical and illustrative of attitudes and arguments in the popular press about Internet culture, and of the popular press in general, which mostly exists to provide people with the kinds of ideas that allow them to bypass serious thinking.

A more measured take on emoticons was offered by essayist Elif Batuman, the literary world’s most charming reactionary.

In a blog post from January 2012, Batuman wondered aloud about the future of the emoticon in realm of literary writing and, by extension, about the future of her own literary palette:

Tonight, reading the final papers from my nonfiction class, I was saddened to discover that one student had not abandoned the habit, which I had critiqued in the past, of using smiley faces in her work. I crossed them out, explaining (again) that powerful writing should generate emotion without emoticons.

Slashing through the third beaming little face, I had a terrible flashback to a moment from my own youth, when an English teacher told me not to use so many exclamation points, because vigorous writing generates energy through language and not punctuation.

I didn’t listen to this teacher. Today I use exclamation points all the time! I don’t think they’re a crutch, so much as another tool in the box. Now I begin to wonder: is that how the next generation will view emoticons? Is one generation’s crutch the next generation’s useful, crutch-shaped mallet?? Have I become an obstruction in the path of literary progress??? Am I now the monster???

??????

????

!!!!!!!!

???????????

;-)

Fast forward from men in the 80s to women in 2013:http://www.toosexyandweird.com/ :)

Thus, if someone sends you a message that says "Have you stopped beating your wife?:-)" you know they are joking.

This 1982 example of emoticon speak among men is very telling.