This text has been written for the proceedings of the international conference "New Perspectives, New Technologies", organized by the Doctoral School Ca' Foscari - IUAV in Arts History and held in Venice and Pordenone, Italy in October 2011

The "portal" designed by Antenna Design to show net based art in the exhibition "Art Entertainment Network", Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, 2000. Courtesy Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.

In the late nineties and during the first decade of this century the term “new media art” became the established label for that broad range of artistic practices that includes works that are created, or in some way deal with, new media technologies. Providing a more detailed definition here would inevitably mean addressing topics beyond the scope of this paper, that I discussed extensively in my book Media, New Media, Postmedia (Quaranta 2010). By way of introduction to the issues discussed in this paper, we can summarize the main argument put forward in the book: that this label, and the practices it applies to, developed mostly in an enclosed social context, sometimes called the “new media art niche”, but that would be better described as an art world in its own right, with its own institutions, professionals, discussion platforms, audience, and economic model, and its own idea of what art is and should be; and that only in recent years has the practice managed to break out of this world, and get presented on the wider platform of contemporary art.

It was at this point in time, and mainly thanks to curators who were actively involved in the presentation of new media art in the contemporary art arena, that the debate about “curating new media (art)” took shape. This debate was triggered by the pioneering work of curators – from Steve Dietz to Jon Ippolito, Benjamin Weil and Christiane Paul – who at the turn of the millennium curated seminal new media art exhibitions for contemporary art museums; and it was – and still is –nurtured by CRUMB - “Curatorial Resource for Upstart Media Bliss” - a platform and mailing list founded by Beryl Graham and Sarah Cook in 2000 within the School of Arts, Design, Media and Culture at the University of Sunderland, UK. As early as 2001, CRUMB organized the first ever meeting of new media curators in the UK as part of BALTIC's pre-opening program – a seminar on Curating New Media held in May 2001.

In the context of this paper, our main reference texts will be CRUMB-related publications, from the proceedings of “Curating New Media” (2001) to Rethinking Curating. Art After New Media (2010), a recent book by Beryl Graham and Sarah Cook; and New Media in the White Cube and Beyond, a book edited by Christiane Paul in 2008. Instead of addressing the specific issues and curatorial models discussed in these publications, we will try to focus on the very foundations of “curating new media”, exploring questions like: does new media art require a specific curatorial model? Does this curatorial model follow the way artists working with new media currently present themselves on the contemporary art platform? How much could “new media art” benefit from a non-specialized approach? Are we curating “new media” or curating “art”?

Vuk Ćosić, History of Art for Airports, 1997. Web project, screenshot.

A medium based definition

“The lowest common denominator for defining new media art seems to be that it is computational and based on algorithms.” (Paul 2008: 3)

“[...] in this book, what is meant by the term new media art is, broadly, art that is made using electronic media technology and that displays any or all of the three behaviours of interactivity, connectivity and computability, in any combination.” (Graham, Cook 2010: 10)

Whatever one may think about new media art, when it comes to curating the definition becomes strictly technical and medium-based. New media art is the art that uses new media technologies as a medium – period. No further complexity is admitted. Beryl Graham and Sarah Cook, for example, in the continuation of the paragraph quoted, seem to be well aware of the sociological complexity of new media art, but willingly put this aside to focus instead on the art that displays “the three behaviours of interactivity, connectivity and computability”, wherever it is shown and whatever it has been labeled [1]. This is no surprise, because – especially when it comes to museum departments – curating has always been medium-based. This model generally works, despite some criticism from curators, especially when the complexity of the medium in question doesn't allow oversimplification. In 2005, writing about video art, David A. Ross said: “Most often, at this point in time, video art is a term of convenience valued by museum conservators who have a professional need to devise proper storage and conservation standards for this specific medium, but even in this situation it is inadequate” (Gianelli, Beccaria 2005: 14 - 15). It is inadequate, Ross goes on, because video has become a ubiquitous medium, one that often makes its appearance in what would be better defined as “mixed media sculptural installations.” The same can also be said for other contemporary art forms such as performance and installation, but it applies to new media even more – a definition that, even in its strictly technical sense, applies to a wide range of forms and behaviors, from computer animation to robotics, from internet based art to biotechnologies.

Of course, both Paul and Graham / Cook – and, generally speaking, all good new media art curators – are fully aware of this complexity, and this awareness shapes their theoretical writing. It is exactly because of this that Graham and Cook, in their book, focus on behaviors rather than on specific forms and languages. At the same time, they are fully aware of new media art's resistance to the white cube and the specific kind of space it offers. As Christiane Paul puts it: “Traditional presentation spaces create exhibition models that are not particularly appropriate for new media art. The white cube creates a “sacred” space and a blank slate for contemplating objects. Most new media is inherently performative and contextual.” (Paul 2008: 56) Paul goes even further, arguing that new media art does not just resist the white cube, but even the kind of understanding provided by the contemporary art world: “New media could never be understood from a strictly art-historical perspective: the history of technology and media sciences plays an equally important role in this art's formation and reception. New media art requires media literacy.” (Paul 2008: 5).

Paul responds to this situation by painting a picture of a curator as less a caretaker of objects and more a mediator, interpreter or producer (Paul 2008: 65). But what does this mediation apply to? Paul implicitly responds to this question when she talks about the average museum / gallery audience, and their common criticisms of the new media art they encounter there. According to Paul, “the museum / gallery audience for new media art might be divided roughly into the following categories: the experts who are familiar with the art form; the fairly small group of those who claim a “natural” aversion to computers and technology and refuse to look at anything presented using them; a relatively young audience that is highly familiar with virtual worlds, interfaces and navigation paradigms but not necessarily accustomed to art that involves these aspects; and those who are open to and interested in the art but need assistance using it and navigating it.” (Paul 2008: 66, my italics). This paragraph already shows that, in most cases, what's at stake is differing levels of familiarity with technology among the audience. This is even more evident when Paul starts considering “recurring criticisms” against new media art – well summed up by the titles of the subsequent chapters: “it's all about technology” [2]; “it doesn't work”; “it belongs in a science museum”; “I work on a computer all day – I don't want to see art on it in my free time”; “I want to look at art – not interact with it” [3]; “where are the special effects?”

Paul concludes that “the intrinsic features of new media art ultimately protect it from being co-opted by the art establishment” (Paul 2008: 74). Yet, this argument can lead us to another, equally (or maybe even more) legitimate conclusion: that technology ultimately prevents new media art from being understood by the contemporary art audience.

Moving the focus

“The hype surrounding the technology driving new media art hasn't helped its long term engagement with the art world...” (Graham, Cook 2010: 39)

This is where a strictly medium-based definition obviously leads. If new media art is rooted in the active use of technology as a medium, there is no way to do without it; and if technology is the main obstacle between new media art and the art audience, all new media curating has to do is attenuate the impact of the technology, and make the art feel more “at home”, albeit artificially. Or, as Vuk Cosic puts it, talking about net-based art: “In my view, when you show online stuff in a gallery space, which is not online, you essentially put it in the wrong place. It's not at home. It's not where it is supposed to be. It's decontextualized; it's shown in a glass test-tube. So whatever you do is just an attempt to make it look more alive. You either move the test-tube or have some fancy lighting. And this is how it works for me.” (Cook, Graham, Martin 2002: 42).

An easy argument against this could be that technology won't be always new. We got used to TV monitors and projectors in galleries; we will get used to computers as well. The youngsters currently drawing their first pictures on an iPhone at the age of two will eventually grow up, and new media art will look more natural to them than it does to us. Yet this is only true up to a point. The hype surrounding the “new media” has not died down over the last two decades, quite the contrary: it burgeons any time a new gadget is launched on the market, reaching an even wider audience. And so far, the art world's resistance to new media art has not been greatly affected by the fact that everyone living in developed countries knows Google, and half of them have a Facebook account.

So, the questions at stake are: if technology is the problem, can curating allow the art audience to access new media art without technology, or at least reduce the impact of technology on the perception of the work? Can the curator become a mediator between art that tackles the social, political and cultural implications of technology, and the art audience, rather than between technology and the art audience, as in the model described by Paul and Graham / Cook? If this is possible, it can only happen, of course, outside of the strictly medium-based definition outlined before, and in the context of a definition that focuses more on new media art's critical engagement with new media and the information age, and on its ability to reach different audiences in different ways: not just the contemporary art audience, but also, on the one hand, the more specialized audience attending new media art events and, on the other, the “bored at work network” [4] that can be reached online.

In other words, if new media curating wants to better serve the practice it supports and the audiences it addresses, it has to shift its focus from the use of technology to other features that are intrinsic to new media art, but that have been sidestepped by the debate around new media curating so far. It has to be more about curating the art that deals with new media, and less about curating the actual new media themselves. Furthermore, it has to take advantage of the intrinsic variability of new media and the adaptability of artists capable of speaking different languages (something that should not be mistaken for conformism) in order to facilitate the presentation of their art to different audiences, and foster a better, broader understanding of their work.

Electroboutique's presentation in the show "Holy Fire. Art of the Digital Age", Bruxelles, iMAL 2008. Image curtesy the author

Against Specialization

“The professional tends to classify and to specialize, to accept uncritically the groundrules of the environment. The groundrules provided by the mass response of his colleagues serve as a pervasive environment of which he is contentedly unaware. The 'expert' is the man who stays put.” (McLuhan, Fiore 1967 (2001): 92)

But why has the debate around new media curating, that, as we said above, involves curators active in the field of contemporary art, and well aware of the problems that the art audience can experience when faced with technology, not yet got the point? It is probably just a case of them uncritically accepting the groundrules of this arena, namely the new media art world. Their ideal audience is probably still that described by Paul as “the experts who are familiar with the art form” - that is, the niche audience of new media art. They probably still place media literacy above art literacy, as a condition for understanding a piece of new media art.

Unfortunately, this approach does not fit in with their declared mission, that is to bring new media art to a broader audience and forge dialogue with other forms of contemporary art. Of course, this mission also includes increasing the audience's familiarity with technology as a medium for art, but it is not limited to that. We could go even further, and say that this is just the last stage of a long journey undertaken to show the contemporary art audience the extraordinary impact of media and technologies on the world we live in, and the importance of increasing our awareness of them for a better understanding of contemporary society – and – as a consequence, the topical nature of the art that engages with them critically, in terms of both medium and content.

This might lead us to conclude that there is no need for the specific figure of the “new media curator”: a contemporary art curator open to new languages and with a good level of media literacy can do an even better job, in terms of picking out what is relevant to a contemporary art audience, working with the artist to find a good way of “translating” the work for the white cube, and forging dialogue with other forms of contemporary art. Perhaps this will be the case in the future. At the present time, the cultural insularity of new media art and the existence of two different art worlds means that specialized curators are still necessary. But new media curating should be reframed, in terms of mediating between two art worlds and two different cultures, rather than mediating between the art audience and technology. It should be about bringing new media art to the art audience in a way that enables it to be accepted as art, and also obliges people to reconsider their preconceptions about what can be accepted as art. With or without technologies.

Oliver Laric, Kopienkritik, 2011. Installation, Skulpturhalle Basel. Image courtesy the artist

Follow the artists

“My interest in technology is in its relationship with culture and its effects on society, and in many cases that can be communicated in things other than code.” (O'Dwyer 2012: 7)

Artists are already showing curators the way along this path. At some point, the artists formerly known as new media artists started taking the problem of how to present their art in the white cube more seriously, and realized that sometimes, putting technology aside was not just a compromise with the market [5], or a way of watering down their works and making them more palatable to the masses, but the right thing to do. It was a process that took time, involved trial and error and ultimately accepting failure, and was eventually facilitated by the emergence of a new generation of artists who enjoyed both bits and atoms, and who didn't see “new” and “old” media in opposition, but as lines of inquiry that should be pursued together, and that can sometimes converge, sometimes diverge, and sometimes criss-cross. A complete, or at least representative, list of examples would go far beyond the scope of this short paper, so I will provide just two recent, random examples. Around the time I started writing this text, I received two press releases: the first announcing that Berlin-based artist Oliver Laric, in conjunction with The Collection and Usher Gallery in Lincoln, had just won the Contemporary Art Society's £60,000 “commission to collect” award; and the second announcing a new work by US born, Paris-based artist Evan Roth, currently on display at the Science Gallery in Dublin. Though the “new media artist” label would be problematic for both, it is hard to dispute the fact that the two artists in question originally attracted the interest of a community of “experts” with their (mostly net-based) early practice. Thanks to the CAS grant, Laric will now be able to create a new work of art for The Collection and Usher Gallery's permanent collection. According to the press release, the work “will employ the latest 3D scanning methods to scan all of the works in The Collection and Usher Gallery's collections – from classical sculpture to archeological finds – with the aim of eliminating historical and material hierarchies and reducing all the works to objects and forms. These scans will be made available to the public to view, download and use for free from the museum's website and other platforms, without copyright restrictions, and can be used for social media and academic research alike. Laric will use the scans himself to create a sculptural collage for the museum, for which the digital data will be combined, 3D printed and cast in acrylic plaster.” [6] The commission allows Laric to bring his ongoing project Versions, started in 2009 with a video essay and developed in subsequent years with other videos, sculptures, installations, to a new level. Versions looks at the issues around copyright, originality and repetition through history, up to the digital age. With the project for The Collection and Usher Gallery, he will give the gallery's audience the chance to learn and think about 3D scanning, digital manipulation, sharing, and the shifting relationship between the physical and the digital, all in the familiar form of a sculptural installation. The online audience, on the other hand, will be able to enjoy and interact with this amazing collection of digital material.

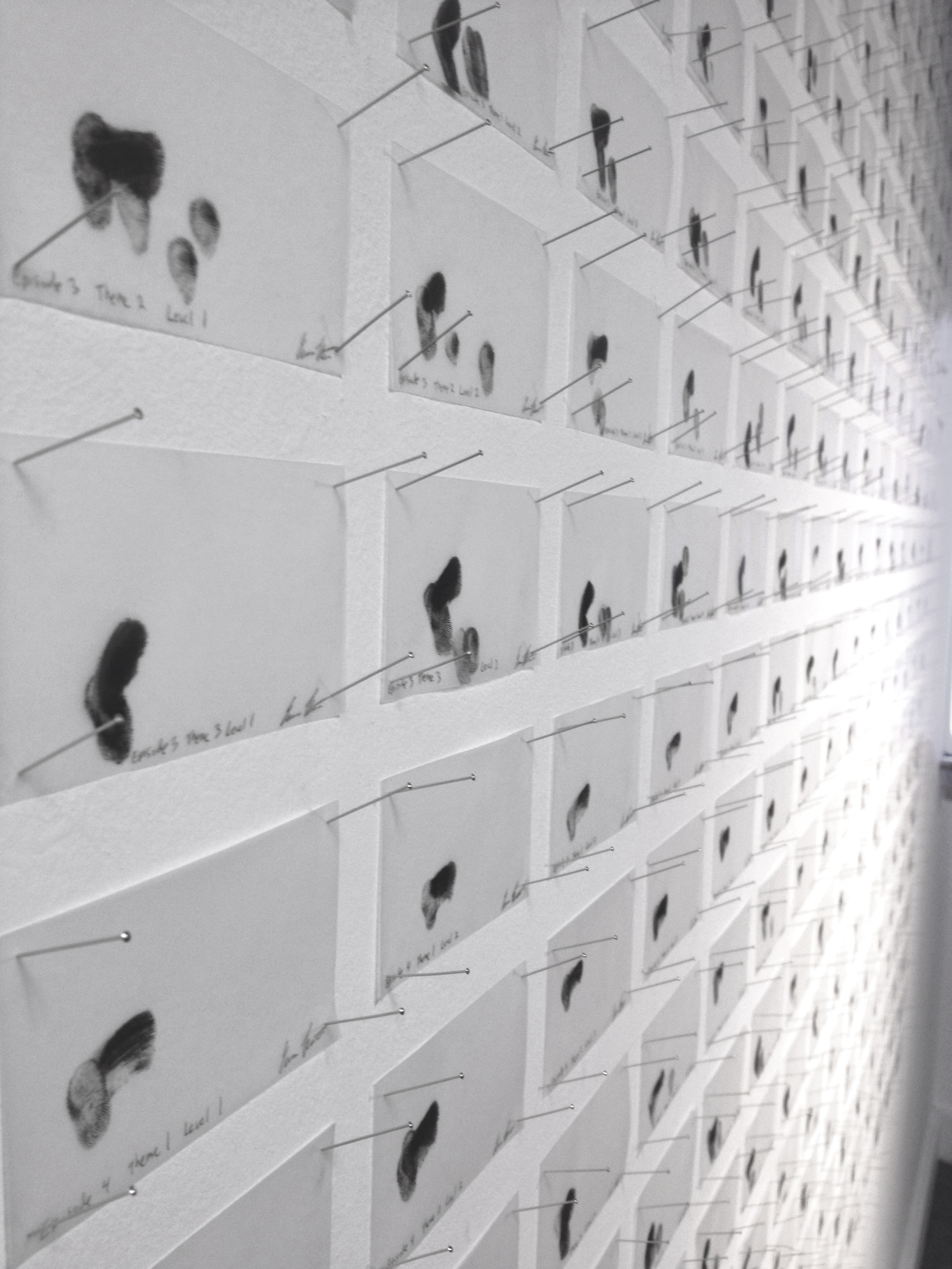

Evan Roth, Angry Birds All Levels, 2012. Ink on tracing paper, 188cm x 150cm. Installation view at the Science Gallery, Dublin, Ireland. Photo by Seb Lee-Delisle, image courtesy Evan Roth.

Angry Birds All Levels (2012) is the telling title of Evan Roth's last work, consisting of 300 sheets of tracing paper and black ink attached to the wall in a grid with small nails. According to the Science Gallery website, it is “a visualization of every finger swipe needed to complete the popular mobile game of the same name. The gestures are visualized on sheets of paper the same size as the iPhone the game was originally created for. Angry Birds is part of a larger series that Roth has been working on over the last year called Multi-Touch Paintings. These compositions are created by performing simple routine tasks on multi-touch handheld computing devices [ranging from unlocking the device to checking Twitter] with inked fingers. The series is a comment on computing and identity, but also creates an archive of this moment in history when we have started to manipulate pixels directly through gestures that we were unfamiliar with just over 5 years ago.” [7] Even if it is on show in a science museum, nobody would ever say it belongs there.

In both works, technology is part of the creative process and one of the issues at stake (but not the only one). In both cases, technology does not feature in the gallery, not out of convenience or for marketing reasons, but because this is what works best for the artwork itself.

In most cases, artists arrived at this point under their own steam, with little help from curators. Are new media curators ready to help them take the next step? If so, they should probably start by focusing on their art rather than their media.

Notes

[1] “Artworks showing these behaviors, but that may be from the wider fields of contemporary art or from life in technological times are included, however.” (Graham, Cook 2010: 10)

[2] As Paul explains: “If a museum visitor is unfamiliar with technology, it automatically becomes the focus of attention – an effect unintended by the artist.” (Paul 2008: 67)

[3] “Art that breaks with the conventions of contemplation and purely private engagement shocks the average museumgoer, disrupting the mind-set that art institutions so carefully cultivated.” (Paul 2008: 71)

[4] The “bored at work network” has been theorized by artist and researcher Jonah Peretti in the frame of the Contagious Media Project. Cf. http://contagiousmedia.org/.

[5] A take on the way new media art circulates in the art market was the exhibition Holy Fire. Art in the Digital Age I curated together with Yves Bernard for the iMAL Centre for Digital Cultures & Technologies in Bruxelles, Belgium (April 18 – 30, 2008). Cf. Bernard, Quaranta 2008.

[6] The press release is available in the News section of the website of the Contemporary Art Society: “Rising star Oliver Laric scoops Contemporary Art Society’s prestigious £60,000 Annual Award 2012 with The Collection and Usher Gallery, Lincoln”, November 20, 2012, http://www.contemporaryartsociety.org/news.

[7] Cf. http://sciencegallery.com/game/angrybirds.

Thanks Domenico for this considered recap on the state of the field, and your generous albeit selective citation of our work. I think we are in general on the same page so I don't want to let linger the implication that our work (by which you mostly mean my and Beryl Graham's book Rethinking Curating) doesn't address "how the curator [can] become a mediator between art that tackles the social, political and cultural implications of technology, and the art audience, rather than between technology and the art audience". In fact we do (and we too suggest following the artists, in the book's second to last chapter). The work of CRUMB has always argued for a redefinition of the boundaries of art as a result of new media art and its inherent questioning of the implications of technology on life. As you have pointed out, our focus on the work's behaviours (with a nod to the Variable Media Initiative) is precisely to get away from any overly deterministic focus on the technology. Your assertion that "new media curating should be reframed, in terms of mediating between two art worlds and two different cultures, rather than mediating between the art audience and technology" is certainly one way to reframe it, and is in part what our book does (and I can't help but point out that the book was written, mostly, in 2006-2007, the timelines of academic publishing being what they are).

But that said, I am not sure that the field of 'new media curating' continues, here at the end of 2012, to be as simple as you've characterised it – there are many more than two art worlds in my mind – but certainly it risks becoming so if we don't continue to complicate it by addressing the various art forms which continue to emerge, _and_ their societal implications. In the exhibition The Art Formerly Known As New Media, which I curated together with Steve Dietz in 2005, we explicitly argued that it wasn't about the media, and the newness of the technology, but about the ideas present in the artworks – what it means to be human, how networks affect us, the protocols of access. This was a tall order given the exhibition was curated to accompany the first biennial conference on Media Art Histories, Refresh, which was very material- and technology- oriented in its initial mapping of a history of new media art (in the time since it has, in part with our hard work on Rewire, started addressing other possible histories). You write that the "debate around new media curating… has not yet got the point" and that "it has to shift its focus from the use of technology to other features that are intrinsic to new media art, but that have been sidestepped by the debate around new media curating so far." Have they really been sidestepped? I've got a decade's worth of postings on the CRUMB discussion list which mostly proves the opposite. It is still a young field, but perhaps it could just as equally be judged on the ongoing curatorial outputs of 'new media curators' as on the most easily accessible texts, some, ours included, which are from half a decade ago – if so, I'd say it's still a pretty rich area of research and interest, encompassing design, science, biology, data, the environment, architecture and lots of other 'worlds' besides the most obvious art one.

Thanks again for bringing these points forward,

Sarah

[img]http://image.shutterstock.com/display_pic_with_logo/501856/501856,1266439205,6/stock-photo-sisyphean-toil-d-isolated-characters-on-white-background-series-46900666.jpg[/img]

Dear Sarah,

thanks for your comment! Let me start saying that, if compared with the amount of research required by the books I discussed, my texts is nothing more that a modest footnote to each of them. You probably know better than me how difficult it is to sum up such a complicated issue in such a small space, and this is why I willingly adopted an affirmative, manifesto-style approach. I agree that we are on the same boat, but I also know that, when one speaks, sometimes it all depends on where she puts the stress. And when you start a book with a sentence like this, in my opinion, you put the stress on the wrong thing, in a way that can't but give birth to a series of misunderstandings:

“[…] in this book, what is meant by the term new media art is, broadly, art that is made using electronic media technology and that displays any or all of the three behaviours of interactivity, connectivity and computability, in any combination.”

I'm just trying to move the stress onward on the "art" part of the "new media art" label. I'm sure that the same issues has been touched many times in the debate around new media curating, but it always happened under the same premise: that new media art is technology-based and that presentations that avoid technology are the result of an act of mediation (a word often replaced with pejorative versions of it). The very fact that the word "art" doesn't appear that often ("Curating New Media" [the book], "New Media Curating" [the mailing list], "New Media in the White Cube and Beyond", "Art after New Media") changes the perception of anything you can say under these headlines.

My feeling is that, if you change the premise, you can later discuss how to bring interactive, computable, online works in the exhibition space in the few cases it is really required. But if you don't, "new media curating" will always be a Sisyphean labor and a pointless effort that doesn't actually help, and maybe damages, the art it wants to support.

Domenico