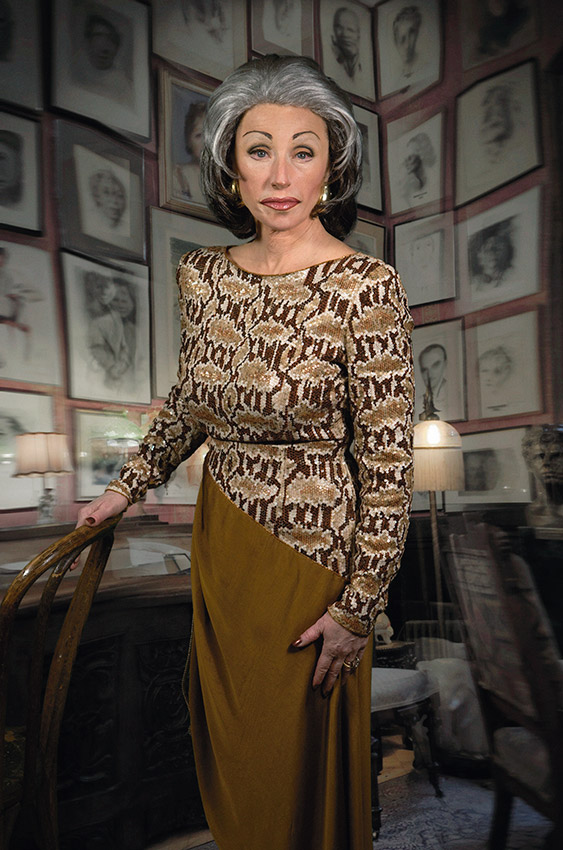

Images from Cindy Sherman's society portraits series (2008.)

Images from Cindy Sherman's society portraits series (2008.)

A friend recently recounted an anecdote about teaching Cindy Sherman’s work to her undergraduate students. She was in the middle of her lecture, explaining Sherman’s elaborate, chameleonic process of casting herself in various roles in her photographs, when one student interrupted, insisting that the photograph projected on screen must have been Photoshopped, that it was impossible that the woman in this image was the same person as in the one before. The others nodded in agreement. Faced with this chorus of disbelief, my friend checked her notes: the image on her slide was from the mid-1980s, several years before Photoshop’s commercial release. The process of creating it was, indeed, analog: the photograph was shot on film, and Sherman’s apparent physical mutation in it the result of costuming and skillfully applied makeup rather than digital manipulation. However, the students’ responses raise interesting questions about how we might conceive of her work in the wake of the digital, particularly since her most recent work has, in fact, made use of such software.

For those of us who first encountered Sherman’s photographs before “Photoshopped” became part of the vernacular, her work carries rather different connotations: it is less about a process of editing or altering the image than one of altering the self through a kind of private performance staged for the camera. Sherman transforms herself, in each image, to the point that she is not only no longer wholly recognizable, but also no longer present as “Cindy Sherman” at all, instead appearing as a litany of characters and stock types. As she noted in an interview with filmmaker John Waters in the catalogue of her current MoMA retrospective, “Before I ever photographed it, I was playing around in costumes and dressing up as characters in my bedroom.”

It is precisely this aspect of dressing up—of adopting and embodying different types—around which much of the critical reception of her work has revolved over the past decades. Moreover, she has maintained a rigorously private studio practice throughout her career, rarely, if ever, working with assistants: Sherman is not only photographer and model, but also hairdresser, costumer, makeup artist, and prop stylist. She performs in front of the camera, but also behind it, adopting multiple roles and functions over the course of creating each photograph. When presented in serial form, the photographs reveal the meticulousness of her process, with each successive image calling further attention to the laborious transformation involved in creating the one preceding it.

Yet over the past decade, Sherman has increasingly embraced the digital, resulting most recently in works that do, in fact, achieve their transformative effects through Photoshop rather than prosthetics, makeup, and careful staging. Her experimentation with working digitally began with the “Clown” series (2003–04), for which she added lurid, patterned backgrounds to images initially shot on slide film, and culminates in the large-scale untitled wall murals she began in 2010, one of which lines the entrance to her MoMA exhibition. In them, her bizarre characters are inserted into a pixelated black-and-white landscape, where they hover flatly against the crudely rendered trees. Moreover, she wears no makeup, transforming her facial features exclusively through digital means, suggesting that Sherman has steadily shifted the orientation of her practice from performance to post-production.

In addition to the murals, the MoMA show includes Untitled #512 (2011), part of a series commissioned by POP magazine, which depicts a figure set against a trompe l’oeil backdrop of a craggy landscape digitally altered to resemble paint on canvas. While these works are overtly manipulated, the use of digital means is more subtle in others: the “Society Portraits” (2008), which cast the artist as aging doyennes, appear less obviously edited than uncannily off. Up close, signs of digital intervention become more apparent: rather than photographing herself in situ, Sherman adds the backgrounds after-the-fact, resulting in awkward, claustrophobic compositions. Wrinkles, pores, and other signs of age are enhanced, making them unabashedly visible.

In one sense, this is a logical step: on a pragmatic level, working digitally offers a quicker, easier way to achieve the same effects—as Sherman noted in a New York Times interview, “it’s horrifying how easy it is to make changes” using Photoshop. It also opens up new possibilities, allowing her to experiment with techniques previously unavailable to her, such as inserting multiple figures into the same image, or placing them in unfamiliar settings. However, for an artist whose work has long been tied to her process, the implications of such a shift seem significant.

Sherman’s photographs have always been ontologically complex, challenging our ability to properly categorize them: they are photographs of Cindy Sherman that are also, simultaneously, not photographs of Cindy Sherman, portraits of the artist in which she is both present and absent. From the beginning of her career, her photographs have insisted upon the constructed nature of images, their potential to manipulate and lie to the viewer, yet they have been anchored by the fact that, on some level, everything in them has actually occurred—she is not a clown, nor an old Hollywood vamp, nor a Renaissance Madonna, but she has dressed like one. The illusion is never seamless: we see incongruous details (a shutter cord in her hand, an obvious prosthesis) that call attention to the fictitious construction of the scenario depicted, but nevertheless, such details also serve to highlight the fact that Sherman has actually constructed it in real life; they are not just images, but documents of her activity.

The digitally altered photographs, too, call attention to their fabrication, but the terms have changed: they lack the implicit tension that underpins the earlier works, between Cindy Sherman as artist who constructs the tableau and Cindy Sherman as model who effaces herself in the image; between the knowledge that the scene is staged and yet, that it has also taken place. Part of what has always been so captivating about her photographs is exactly what made my friend’s student insist that they were faked: no matter how convincing her costume, her staging, her makeup, we know that the same woman lies underneath it.

What to make of this turn toward the digital? In spite of her embrace of software, Sherman’s work is still made for the gallery rather than the screen. Just as the “Film Stills” mimic the old promotional stills produced by movie studios not only through style, but also print size and paper type, the “Society Portraits” echo the gaudy, overlarge scale of a wealthy patroness’s portrait, resembling the sort of thing that might hang in one of her subjects’ living rooms. Even the murals, though they escape the frame, are resolutely oriented in the material, quite literally bound to a physical space.

At first, I couldn’t help but feel that by exchanging the elaborate masquerade for Photoshop, Sherman was, somehow, cheating. But perhaps this new direction is fitting: though they have often been read in terms of performance, Sherman’s photographs have always been, at their core, images about images: about the way images function, how they are created, trafficked, and coded, the ways in which they manufacture and disseminate meaning. Now that Photoshop has become the norm, we know better than to have faith in their fidelity—we assume that what we see is mediated, altered, and edited, regardless of whether it is an Instagrammed iPhone snapshot or an airbrushed celebrity on the cover of a magazine.

Throughout her career, Sherman has been singularly attuned to the cultural role of images, and her digital works, too, capture and comment on the way we understand photographs today—not as documents of reality, but as raw materials that can be endlessly refashioned.

The work seems trivial, elevated by a conjunction of ascendant postmodernism and a branch of feminism. It seems to me that we humans have always known that "raw materials … can be endlessly refashioned." And, critiqued from a performance art standpoint, Shermans "roles" were not apparently held for any more time than necessary to shoot the photo.

This work got me thinking about some of the same questions:[Worn Outing][http://t.co/c2Gigwd7]

visual arts analog talking pictures ((a/k/a radio (1920s- "images of the mind" vs natural radio))

Vis-à-vis (Cindy Sherman's analog photographs); I recall the attribution to some of my soundworks as being either electronically DSPd or computer manipulated. Having fleshed out my SAIChicago MFA 1972, wrapping up two University teachings 2002, on through 2012- I do know intuitive satisfaction for having evolved personal acoustic concepts which at base, writing retrospectively, were guided by long term memories.

My intuitive terrain vantage during 1970s-1980s assumed: sound was not to be derived from (dj) microphones but, initially, the mono accelerometer (analog sensor). On through the cassette-sharing years of these raw soundings, on one of the tracks, I inserted my name in Morse code, sometimes at x speed and at a very low level. Having done so for awhile, this ended abruptly; my thinking was that these unheard vibrational natural phenomena sources were potentially available to everyone on "spaceship earth" - they're ours to behold.

Parenthetically though, I was experimenting with complex sources and the unique aspects/nuances between sound and music. I pressed on. I'll stop here, as my middle name is suono.

Most of my soundworks (audio audio or video) are either public domain or in my archived, autobiographical external HD. Importantly though -to import sound- the preferred solar sensor/preamplifier I/O was the key to earphone listening from the multitude of terrestrial wave forms. My now defunct freetoears.net pages is a failed attempted to achieve the then desired net-outreach.

Into this head wind, 'my intercepted compositions' meandered DECK II, SoundDesigner I and II, with reliance upon synced layered tracks using multi year recordings, each w/time, day, date, WWV voice&signal. The 1990s challenged; tempting me into multiple tracks w/software inducements. Earlier, I had receive 100 Shadow sensors from the Erlangen Germany owner.

I was still on course to overhear (even speedup very low frequencies) from '200 + found sounds in nature.' This turned out not to be a problem after having attached 11 of these Shadows to a 50 year old Birch tree! (After all, there are more natural vibrations "in heaven and Earth that are thought of.") The purist in me was satisfied.

When will anyone ever mirror and comprehend, in realtime, this analog/digital supraterrestrial trove. Conceptually, I could lock onto a flow chart, RF transmissions, modulated laser, optic & fibre sensors' A/D I/O sampling/multiplexing/demultiplexing- in two-way realtime stream outs - as audio/video directly to and from your hand held. The temptation was Audiomedia I & II; eventually digi002- when I began borrowing from my 5, 7 & 12" raw analog Norelco, Sony, Nagra, Scotch 601 master and cassette tapes - this audio I/O was from direct contact to the various gauges of galvanized wires, including 1/2" brass windribbon, with using mono & triaxial accelerometers, strain gauges, Shadows and DiMarzio sensors.

I did have limited realtime events in which I simultaneously used a He-Ne modulated laser to transmit aspects of the whole from the then "Permanent Forest Terrain Instruments." Some public releases: "Musicworks," "MITEK," "Audio Arts," "Nonsequitur." "Earlabs," "Aerial," "Tiln," "¿What Next?," "KUNSTradio," "Zero Trace FACT" "Deadtech " and "ACOWO" were networkable samplings from this Lat46.812716 Long-092.059014, and provided in-progress-projects to obtain grants from the NEA, Jerome, NEA, Minnesota Arts Board, University of Minnesota Graduate School.

I did come close to lots more three times. An Intel 8080 microprocessor (200 inputs, keyboard-controlled 200+ outputs) at New Music America, Minneapolis 1980 and at the Hudson River Museum, NYC 1982. Both public performances used grant money to achieve Westar V satellite up/down links to relay analog-mixed realtime sounds via a telephone-delivered 2 channel pair from Duluth Minnesota- to these locations.

Shortly before retirement from UMD 2002 email traffic between the Microflown (sensor) founder and I documented a special UMD price for a single sensing element- used in a larger array -which was a "sonic particle camera." Third party paper work did not get synced, the deadline came and went and so did I.

At this moment. Analogs', Sounds', Musics' thoughts' from all of us - in evolving states- it's samo process who. what, where, when, why, how, NOW analog to nando/digital.

Unprecedented challenges for earfulls; and NASA's eyes/ears (w/Sagan Mars mic!) realtime, outputing to hand helds- via two-way on-call streams - are underway. Perhaps generations later, listening/seeing Global's imaging & sound tracks will have both at par.

leif BRUSH

nano/digital

The article is interesting from a cultural standpoint. Thank you.

Materially, perhaps this shift in Cindy Sherman's practice is indicative of a manipulation in meatspace vs virtualspace.

The difference being the limitations of meatspace (her earlier work) are harder to overcome, thus lending a greater aura of disbelief when encountered by it.

There is thus an "ideal" conception which the image reacts against, and the valley between expectation (from ideal) and what we see is what creates a reaction.

The ideal conception is bound against a network of constraints: material, gravitational, fabrication, etc.

Her manipulations in virtualspace, floating in a limitless boundary, doesn't inspire such a viscercal response.

Perhaps because the boundless possibilites of bits present no "ideal" to agitate or react to.

The question I wonder is if there is in fact an absolute boundary which we can agitate in virtual space. The best reactions that have been inspired within me are those that react to a cultural expectation, which is immaterial.

Put another way: what is the material of virtual-ness, and how can one conflict with it and upset expectations?