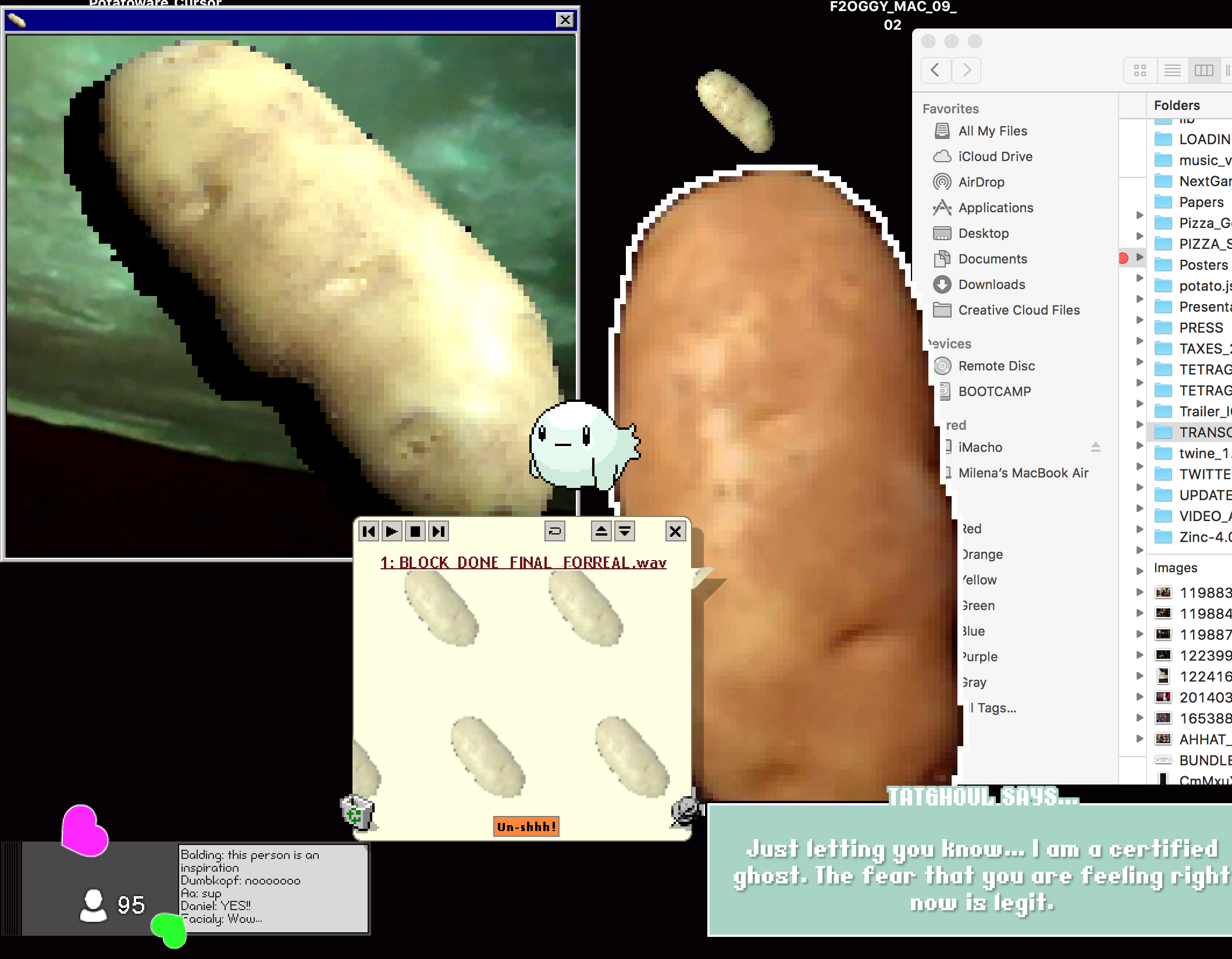

Nathalie Lawhead, (☞゚ヮ゚)☞ unleashed desktop pets, 2015. Screenshot of a bunch of Nathalie’s software running at once. Courtesy of Nathalie Lawhead.

The latest in a series of interviews with artists who have a significant body of work that makes use of or responds to network culture and digital technologies.

Ryan Kuo: I first encountered your practice when a version of Tetrageddon won the Nuovo Award at the 2015 Independent Games Festival. Like your other works, it far exceeds the usual understanding of a game as an enclosed space with winners and losers. For example, the 2021 version of Tetrageddon primarily occurs within a fictional and functioning desktop environment, and your 2020 “ARG-like” adventure Mackerelmedia Fish opens as an abandoned Web 1.0 site. Some of the things a person encounters when exploring these works are: explosions of pop-ups; new browser tabs that open dead-ends; a EULA agreement; Tamagotchi-like desktop pets; complete mini-game compilations; a SurveyMonkey questionnaire; links back to your itch.io projects; open directories containing surreal GIFs and branching ASCII adventures written into an .htaccess file; the system print dialog with illustrated PDFs ready to print; and countless graceful animations and sound collages that bookend and weave these elements together. Tetrageddon features the slogan, “This is what the internet does to people.” Taking your own lived experience of the internet, which are the moments that you most strongly want to convey?

Nathalie Lawhead: What I love about this is that all of what you described about my own work is exactly what existing on a computer is like. It's bizarre, noisy, nonsensical, random, uncontrollable, kind of aggravating, and completely chaotic. The desktop that you exist on with nonstop app alerts or pop-ups, the way you check email and must navigate through spam, the way you try to read a news article and have to very carefully maneuver around banner ads that trick you into clicking. Everything is a weird attention-seeking minefield. It's amazing that we get anything done.

I don't think there's anything about the digital world that really makes sense. It's such a weird type of virtual “void” to exist in, and somehow we all agreed that we need it. It's like we inadvertently invented a metaphoric realm for our minds to get trapped in.

I remember when the internet was still new and you had to “pitch” it to people. You had to explain what a website is and why they needed one and also why they should visit your website. The puzzled looks on people's faces were priceless. But the one thing that was hard to argue with was that the internet is not “real.” So why even care?

Today we all agree that it's real, but it's only real because we all use it. It's so beautifully arbitrary.

I love trying to convey this feeling in my own work. I want someone to find a door into one of my websites and think, "Wow, this is so weird!" and they can't stop digging into it because the weirdness is what's enticing. One of my favorite first memories about being on a computer is this overwhelming feeling of how bizarre it all is. I want to keep that love alive.

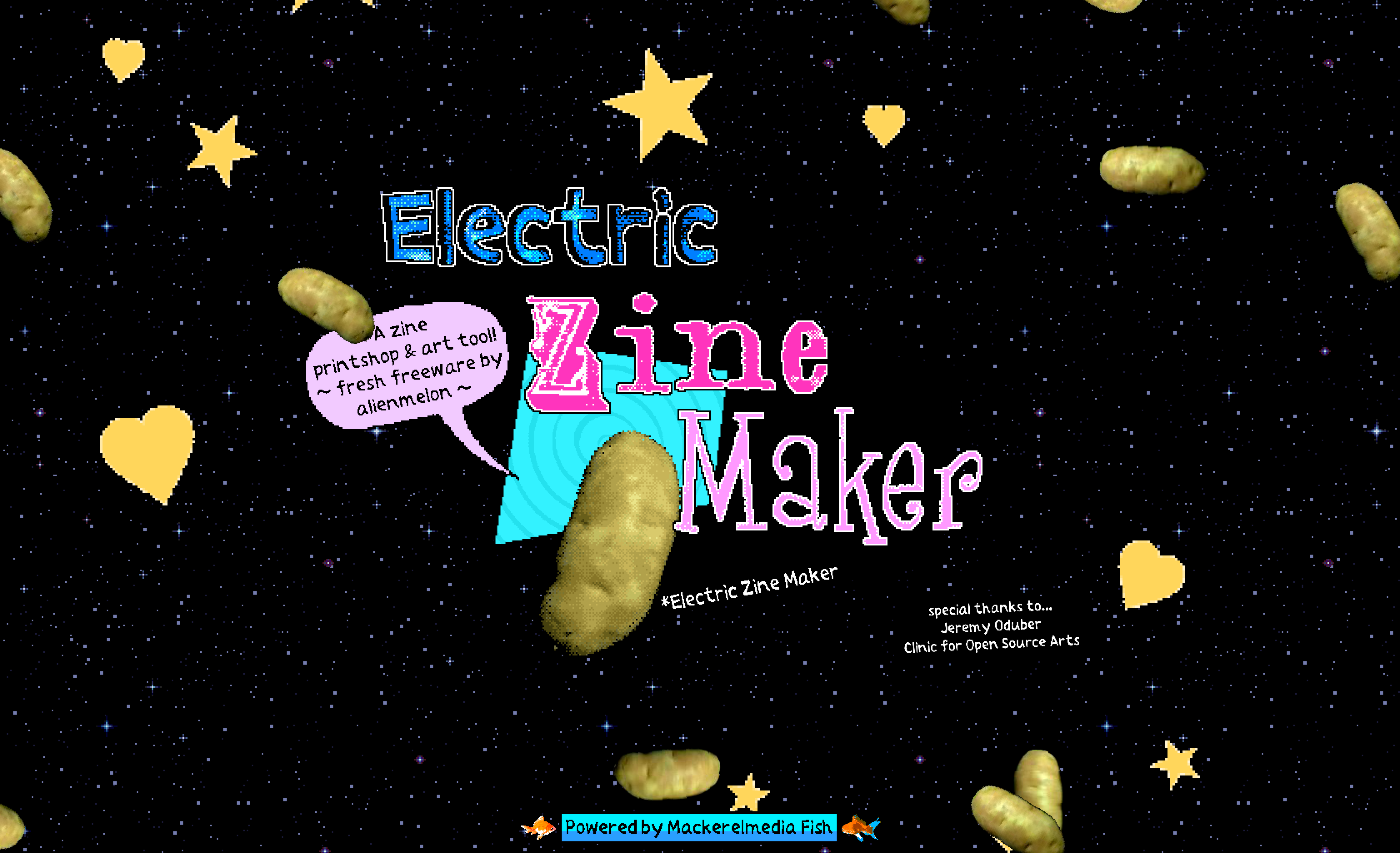

Nathalie Lawhead, splash screen from Mackerelmedia Fish, 2020. Website. Courtesy of Nathalie Lawhead.

RK: One could argue that the hyperlinks, sudden detours, and leaps of faith between the various platforms and formats in your works exemplify “network culture” as championed by Rhizome. However, you’ve said that when you started your practice in the late ’90s, “it was considered net art, but my interest in art on computers has always been more complex than that.” How do you presently relate to the “net art” term, and do you still find it to be insufficient?

NL: During that time, when I started in the late ’90s, “net art” was the term people had for “weird art on the internet."” It was pretty much all we had. What is a website and what is its relationship to art? Can a website itself be art? What is the role of art on the internet, even?

I’ve written a lot about how websites were viewed under that artistic lens, especially the Flash website movement. Many developers, artists, and agencies were creating these top-of-the line websites all based in Flash. They had their own interactive language, soundtracks were made for them, everything had to transition, there was animation... Actual money was being poured into them to make them as immersive as possible. People even asserted that websites were the new “emerging artform.”

Many artists made a name for themselves here. It’s hard to convey how influential all that was because it’s so forgotten. With the death of Flash, this movement largely disappeared. We don’t view websites as much more than something to scroll through. Interacting with a website has become our virtual version of a liminal space, rather than the destination itself. Flash makes a big case for the importance of preservation, too. So many interesting concepts, ideals, and design models were being explored here.

I really miss the early web because it felt like everyone was trying to reinvent the wheel. There's something beautiful about a space where nobody really knows what they are doing or what they are even doing it for. I recognize a lot of these mentalities in the small indie-game movement today. The label “game” has become this larger umbrella term to encapsulate even “weird art on the computer.” It loses its meaning, and that’s when it’s the most interesting.

I liked the term “net art” more though, because it seemed a lot more specific to “websites as art,” and I feel like digital art lost that philosophy. Our relationship to the internet has changed. Especially creatively. I think I appreciate net art more today, when it has basically dissolved into nostalgia, than I did back then.

Labels have always been hard for me because they introduce so many misunderstandings. When people were calling my work “net art,” some would argue that it was “too much like a game,” or too polished, or too different, or too much Flash and not enough HTML. When people started calling my work “game,” this introduced its own misunderstandings. Then there was not enough of a “goal” to be “playing” it. The art wasn't entertaining enough. I still look back at how places like Jay Is Games reacted to my work, and get a good laugh from that. The way mentalities, like computer literacy, have shifted to give understanding and room to art on computers that is different is encouraging.

I think computer art still doesn’t have enough of a history for labels to really mean something. The labels don’t seem to stick beyond being arbitrary buzzwords. For example, my own work went from being labeled as net art, to fancy-sounding things like literary hypermedia, to rich media, to just being lumped into “games” now... The work itself hasn't really changed in terms of what it’s doing, but the labels have.

Screenshot from Nathalie Lawhead, 👻 desktop haunted by software of the past 😱, 2018. Cursed executable. Courtesy of Nathalie Lawhead.

Screenshot from Nathalie Lawhead, 👻 desktop haunted by software of the past 😱, 2018. Cursed executable. Courtesy of Nathalie Lawhead.

RK: There’s a line in your interactive zine Everything is going to be OK that states, “Everything is so highly efficient but unintuitive at the same time.” In much of your work, a person is not an agent but a provider of confused impulses that nudge the work into action. Your work asserts its own logic, and a person has to follow. Often the effect is to disarm and make a person vulnerable to your experience. Rather than an exercise of power, I’m wondering if this is an expression of solidarity against forces that can seem insurmountable. Everything is going to be OK very carefully guides a person through matters of rejection, abuse, poverty, and suicidal ideation. In your practice, does the removal of control create empathy by design? Or can this play other roles?

NL: It’s interesting to see that people consistently get that impression from my work. It’s important to me to highlight an absolute lack of control in a ridiculously chaotic environment, because I think this is strongly undervalued.

I feel that this is how life is. Things are insurmountable. You are up against forces beyond your control. You just barely manage, sometimes… Engaging with a computer is so much about control. So is entertainment in general. It’s expected to function under comprehensible rules. It makes sense, when life doesn’t.

There's something really cathartic about absolutely losing control. Acknowledging that control doesn’t really exist. That you have no power in a situation. Just trying to roll with whatever is thrown at you, and try to make sense of it. Life is like that. Maybe it’s informed by my own personal experiences just trying to survive things, so it's something I try to draw on more.

Art on computers, games especially, lend themselves well to reversing the power dynamic a computer user expects. Control becomes loss of control. I like expressing the feeling of being placed in a position of navigating something you don't understand. I think it’s easy to view games, or interacting with computers, as something like “power fantasies.” We are always in charge. Everything revolves around the player or user. It’s also a mindset that I think doesn't reflect the experiences of a lot of people.

To me, power comes from your own strength to survive something horrible, not how you exercise control. I don’t think you can convey that if you make something where the player can “win’ and defeat the monsters. But when you design around “loss of control,” it does create room for empathy. It's definitely about solidarity.

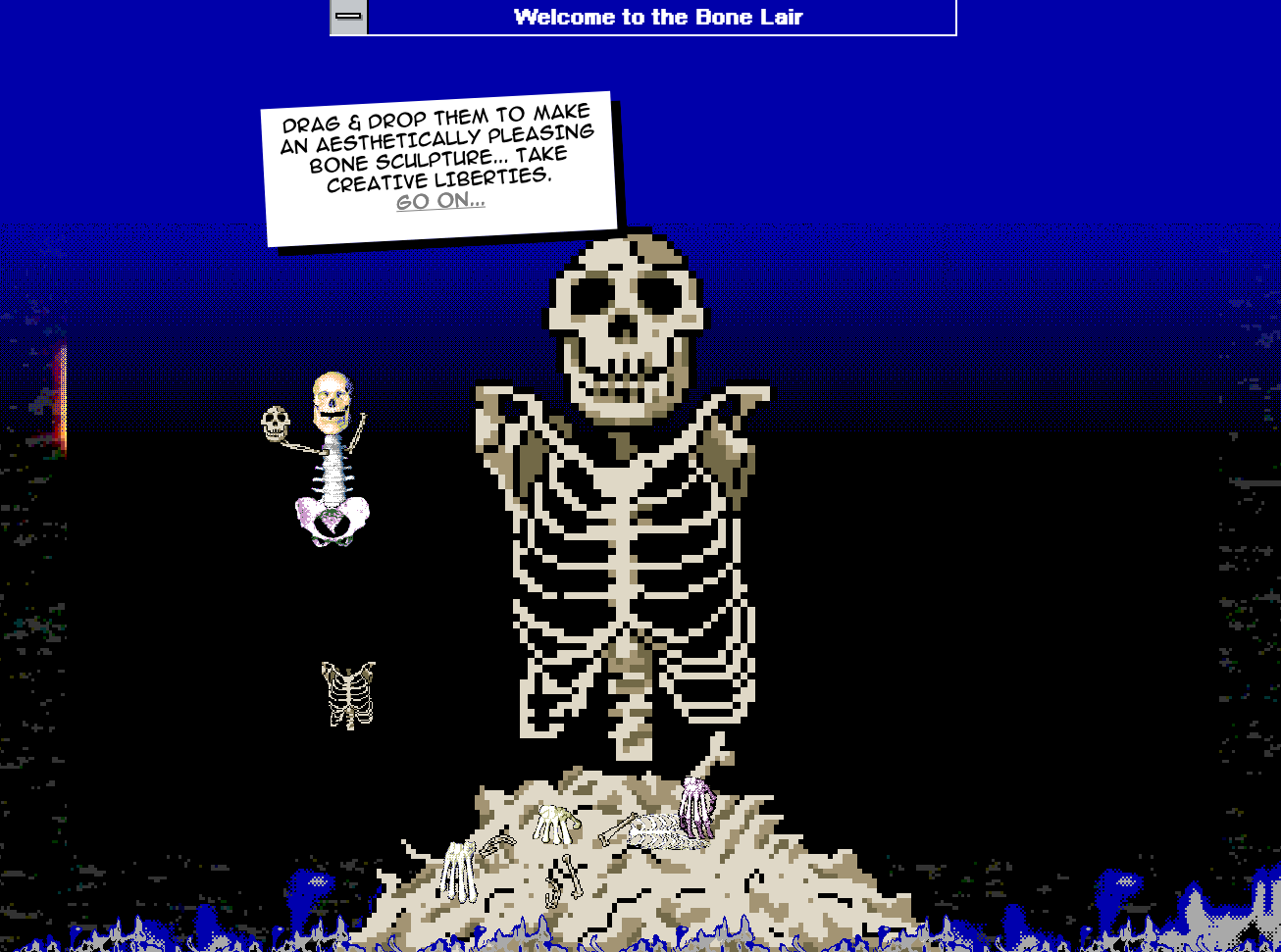

Most of my work just goofs around with that, but in Everything is going to be OK I wanted to convey that loss of control in a way where people could really understand struggle. Screenshot from Nathalie Lawhead, The Bone Lair, 2021, A Backwater Website. Courtesy of Nathalie Lawhead.

Screenshot from Nathalie Lawhead, The Bone Lair, 2021, A Backwater Website. Courtesy of Nathalie Lawhead.

RK: I really admire how you not only state, but literally manifest, the themes of survival and self-preservation in your work. You consider digital art to be inherently ephemeral, and so your works depict graveyards and dismembered, skeletal systems that literally fall apart at the touch. Spirits and vermin inhabit these spaces, and as the creator, you are ever-present. You are both self-aware and prophetic about the eventual death of your work, which frequently reads like its own eulogy. How does your physical body relate to the digital structures you create?

NL: Oh man... That's well said. Yes, I'm constantly tormented by the inevitable doom of my work. I keep making it and now I have to maintain something like 40 games. I have to update them, make sure they are all converted from 32-bit to 64-bit, and don't get wiped out by major OS updates. The struggle to not let it just vanish into the digital void is real.

The ephemeral nature of digital art fascinates me, but it's also terrifying. As an artist, I want to be remembered for my art. I want people to enjoy it long after I'm gone. At least that's the promise of art. Art definitely becomes more meaningful when it ages, and when it's taken out of context of the zeitgeist it was made under. You can't have that with digital art. An indie game today will last about five years before becoming obsolete or just unplayable. It seems so irrational to me that you can spend more years making a game than it will be playable.

My grandfather was a sculptor. He made these welded metal sculptures depicting scenes from Eastern Europe. They documented the history in Slovenia, from his early peasant life to the wars that happened there. You can still see the work he made in the ’80s. Those pieces exist in the same state as the day he finished working on them.

I can't say that for my work. I have to let go. I have to accept that I will be forgotten. When I first started, I thought that digital art was THE way to exist. The supposed permanence of it was what I naively thought of as a big selling point. It would live forever because I didn't have to worry about decay, or erosion, or things getting lost... The opposite ended up being true. There's something inherently beautiful and haunting about that.

The way digital art and our virtual spaces decompose is nothing short of poetic. They slowly stop working. Things silently vanish. You see this digital skeleton of missing images, things moving but they no longer have the graphics associated with them, pieces are gone, but there's this ghost that you're now looking at. It becomes something else.

I know it can be depressing if you want to make work that will properly last, but it's sure beautiful to create in formats that never existed in the first place.

My grandfather used to make fun of computer art because it's not "real." It's not tangible. It doesn't exist in the world. He was right. It doesn't exist. That's why it's special. It's already a memory.

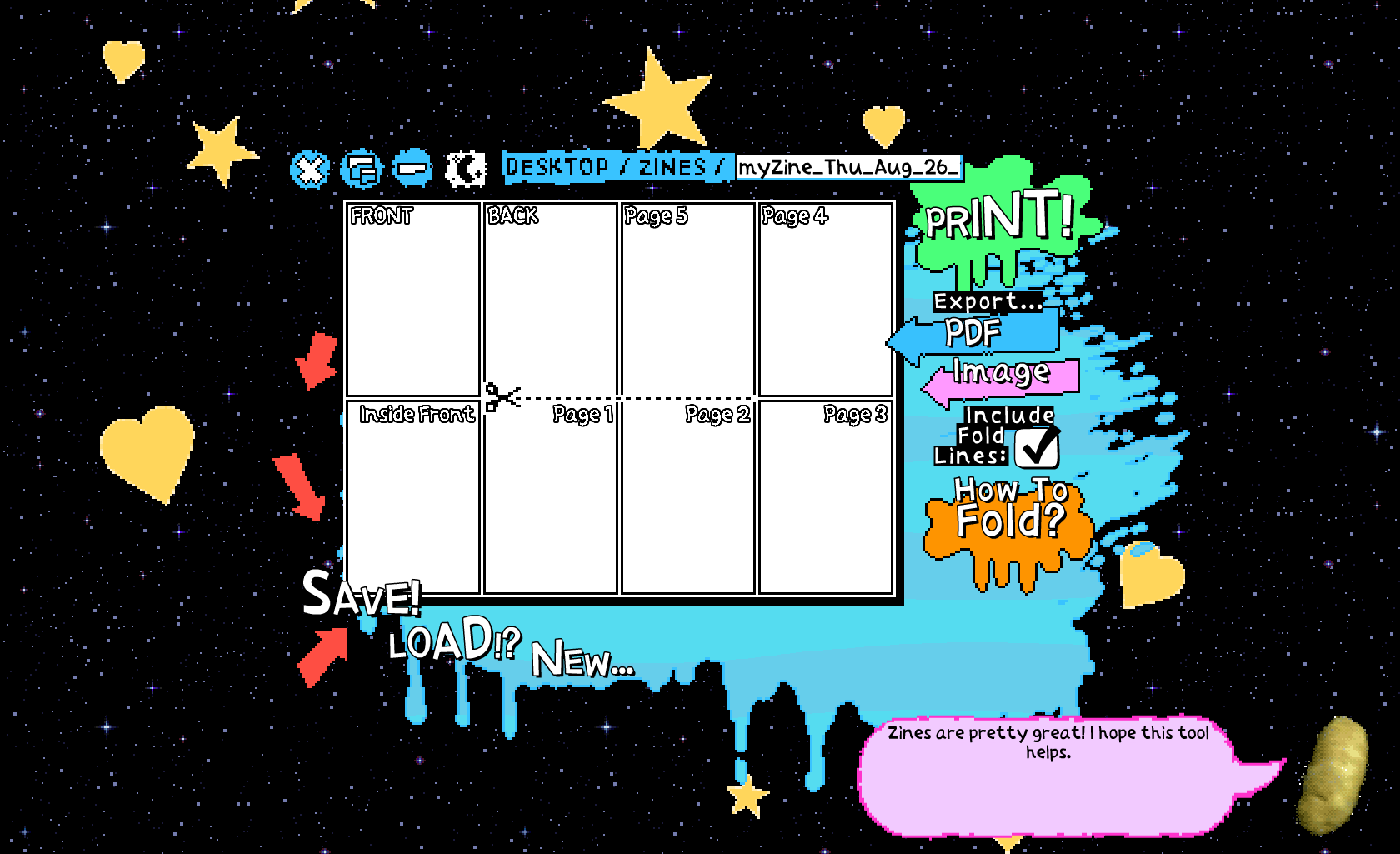

Screenshots from Nathalie Lawhead, Electric Zine Maker, 2021, Software. Courtesy of Nathalie Lawhead.

Screenshots from Nathalie Lawhead, Electric Zine Maker, 2021, Software. Courtesy of Nathalie Lawhead.

RK: You are a strong advocate of experimental tools released independently by developers and hobbyists, a world away from the forced updates, siloed marketplaces, and endless forward motion of the tech industry. By their nature, these tools can suddenly appear and just as quickly vanish. As you’ve written, the act of stumbling across a file on your hard drive, and remembering or forgetting how it came to be, is uniquely meaningful. One of your current works in progress, Electric Zine Maker, is a collaborative tool made in this vein. Where do you envision this project in the near and distant future?

NL: It’s probably very On Brand that I envision the Electric Zine Maker disappearing, too… slowly but eventually. I worry about the future of these experimental tools in a space that is incrementally becoming more and more hostile to things created by independent software developers. Will they get pushed out under the guise of progress? Will we forget the ease of access and creative freedom we have as developers, and just accept a monopolized space? The bar for building and freely distributing your own things (like websites, web apps, or tools) is steadily being raised. I’m not the only developer talking about how difficult the ease of access to newcomers is today, compared to how it was when my generation was starting out. It's getting harder to self-publish software in many contexts. Web development itself has become a convoluted nightmare, especially to new people. It’s just as much about “keeping the dream alive” as it is about making cool things.

I recently upgraded my Mac to the latest OS and it’s a bigger struggle than ever to run my development environment on it. The modern software ecosystem wants you to be licensed, use proprietary tools, pay to exist. It’s hard to build software without worrying about how expensive it’s getting.

Maybe my view of this is bleak because I loved Flash, and saw it slowly get smothered out of the modern web. If it could happen to something as ubiquitous and commonplace as Flash was, as friendly and normal it was for every hobbyist developer to use it, then it’s hard not to see that happening in other aspects of our digital world.

Flash’s overuse, especially in the context of banner ads, made it a popular target to exploit. You see banner ads giving JavaScript today a similarly bad reputation. We’re putting interesting artistic experimental work in the browser in a risky position because the driving decision makers behind the web, like Google, are making choices based on these common commercial issues. Bad banner ads need to be “controlled,” so (for example) a change to HTML5's audio autoplay happens, and this breaks every HTML5 game ever. The niche developer base behind browser games doesn’t matter as much as advertisements... So these shifts are slowly pushing anyone else that is making experimental work off the web.

Electric Zine Maker was built to capture the old experimental Flash space. Silly coding experiments that people were sharing as memes. How uniquely weird things looked. A lot of the tools in it are re-built Flash experiments. I'm hoping to kind of keep that creative “tone” alive in the tool, so people can create with that little bit of history. The zines made in the Electric Zine Maker will likely outlive the tool itself because image formats live longer than apps. I would love it if the Electric Zine Maker could live beyond my own support for it. The difficult thing about tools made by individual developers is that they rely on that one person to keep maintaining them.

Maybe there will be a shift in mainstream computer culture that suddenly wakes up to the pressing importance of preservation. Maybe the Electric Zine Maker will be able to keep living the same way that people keep bringing back things like Kid Pix. Right now, if you ask me about the future of any of my work I would look to digital preservation as a source of hope, or even people being inspired by my work and making their own throwback to it once it’s gone.

I think our digital history kind of lives like oral tradition folktales. Concepts are passed on as nostalgic throwbacks, like a programming version of word of mouth. I made the Electric Zine Maker throwing back to the Flash days of the early internet; someone else will make a tool inspired by the Electric Zine Maker throwing back to the Kid Pix days... You can’t keep it exactly as it was, but it keeps being passed down as reiterations of itself.

I hope my work, like the Electric Zine Maker, will inspire others that would make similar things. I think that's the best future anyone can ask for as a digital artist.

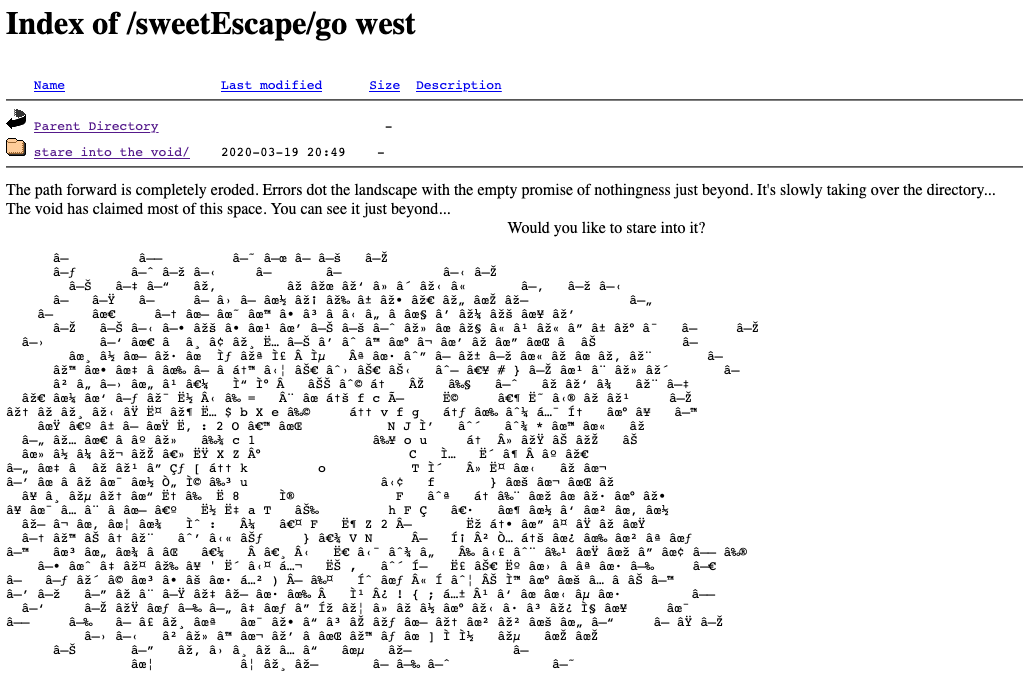

Screenshot from Nathalie Lawhead, ⚠ The Sweet Escape Open Directory ⚠, 2020, Forgotten Website. Courtesy of Nathalie Lawhead.

Screenshot from Nathalie Lawhead, ⚠ The Sweet Escape Open Directory ⚠, 2020, Forgotten Website. Courtesy of Nathalie Lawhead.

---

Age (if you’d like to share): I'm one year younger than Britney Spears. That’s how I remember.

Location: Irvine, California.

How/when did you begin working creatively with technology?

I started in the late ’90s, early ’00s. Art on the internet fascinated me because it could react, move, and was not stuck in a single space. I got hooked and have been with this ever since.

What did you study at school or elsewhere?

I started studying classic art, but really wanted to make net-arty things. Nobody was teaching this at any university. I did check too! Some of them were even including my stuff in their curriculum, so it kind of made me feel like I didn't need it then. They didn’t have these types of programs at the time. I taught myself. I’m not sure if this was the best route because I can't boast about having a fancy education. It sure feeds into impostor syndrome when I’m talking to very smart professors that invite me to give talks at their universities! It's good irony... Either way, I don’t think I would be doing what I love doing if I had gone the conventional path.

What do you do for a living or what occupations have you held previously?

I’m a freelance web developer. I’ve done work for Disney.com, and other places I can’t remember. I’ve been at it for a very long time. My dream has always been to make my art. I sustain myself however I need to, or sacrifice what I need to, in order to do that. I love doing this. It’s life for me.

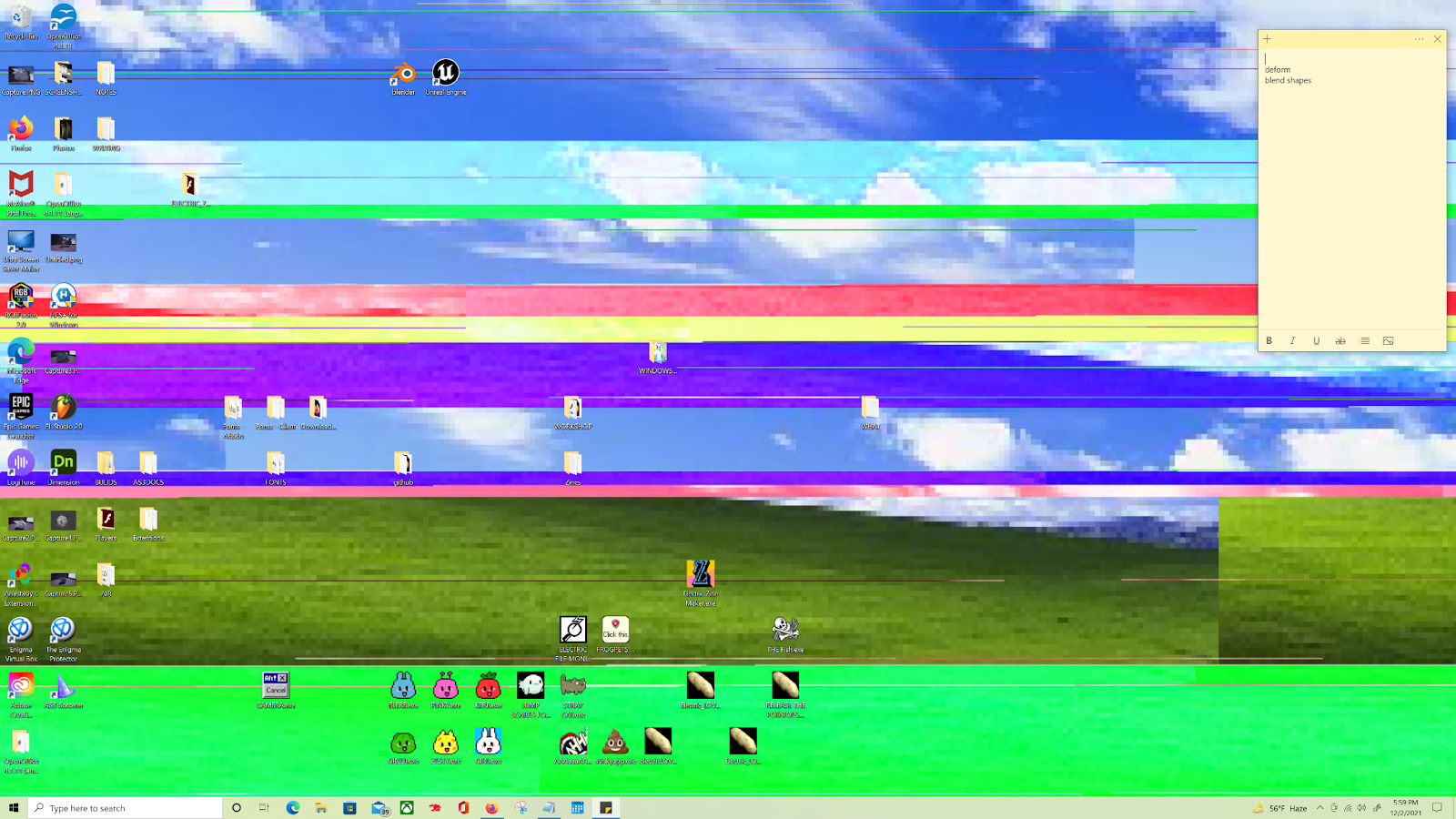

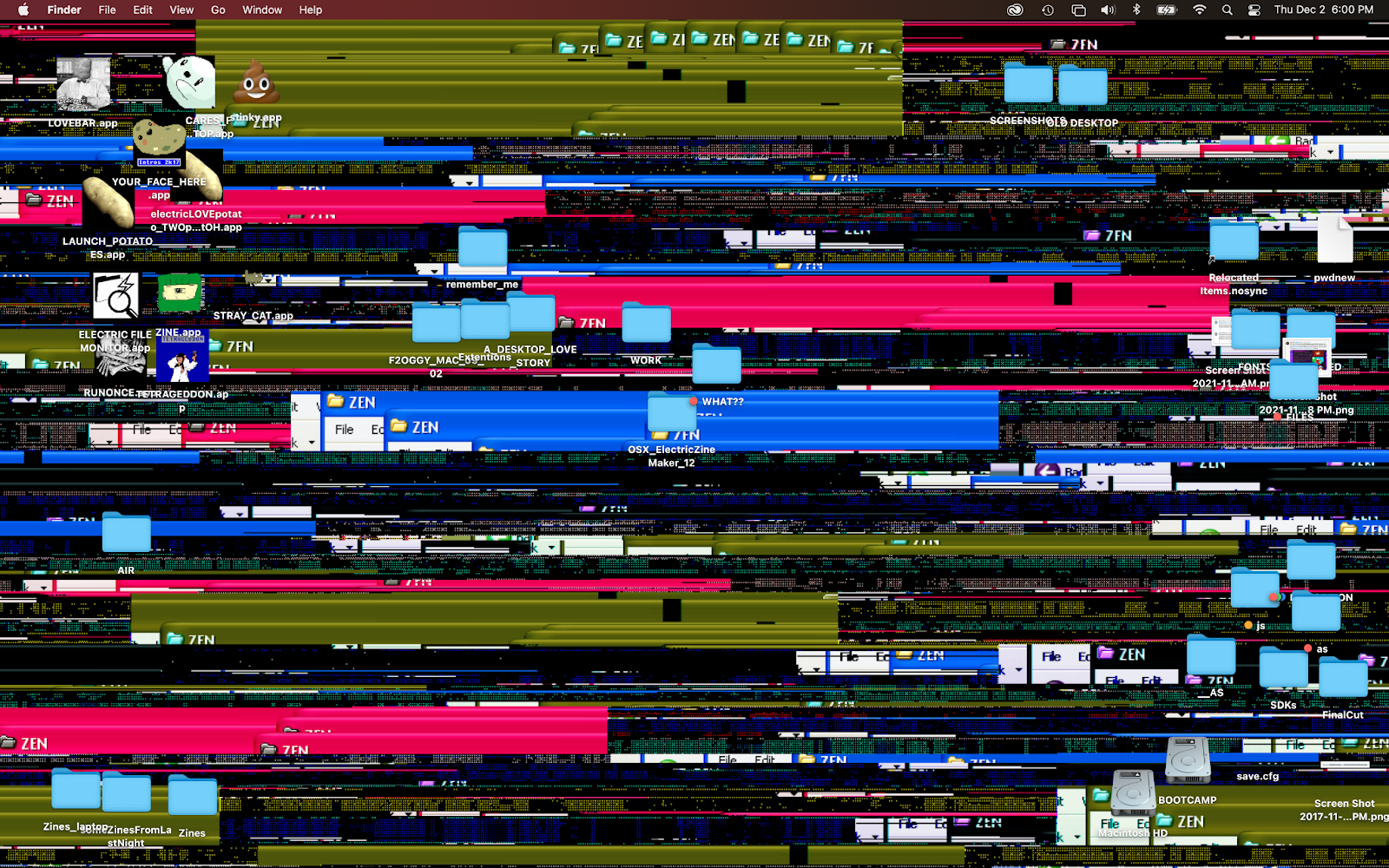

What does your desktop or workspace look like? (Pics or screenshots please!)

- Windows :D

- macOS :)

Nathalie’s Windows Desktop 😱, 2021.

Nathalie’s Windows Desktop 😱, 2021.

Nathalie’s ❌macOS⛔ Desktop, 2021.

Nathalie’s ❌macOS⛔ Desktop, 2021.