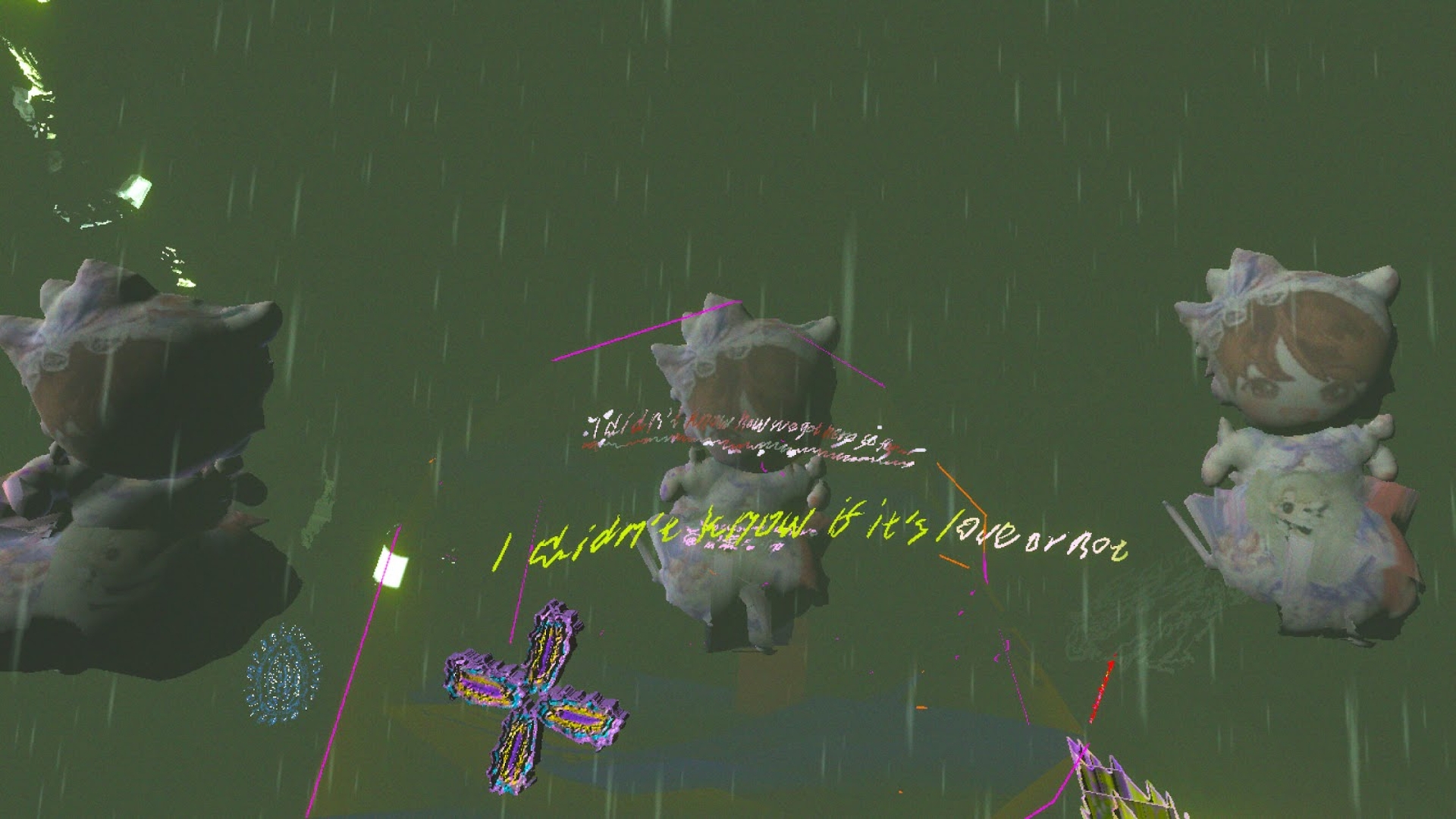

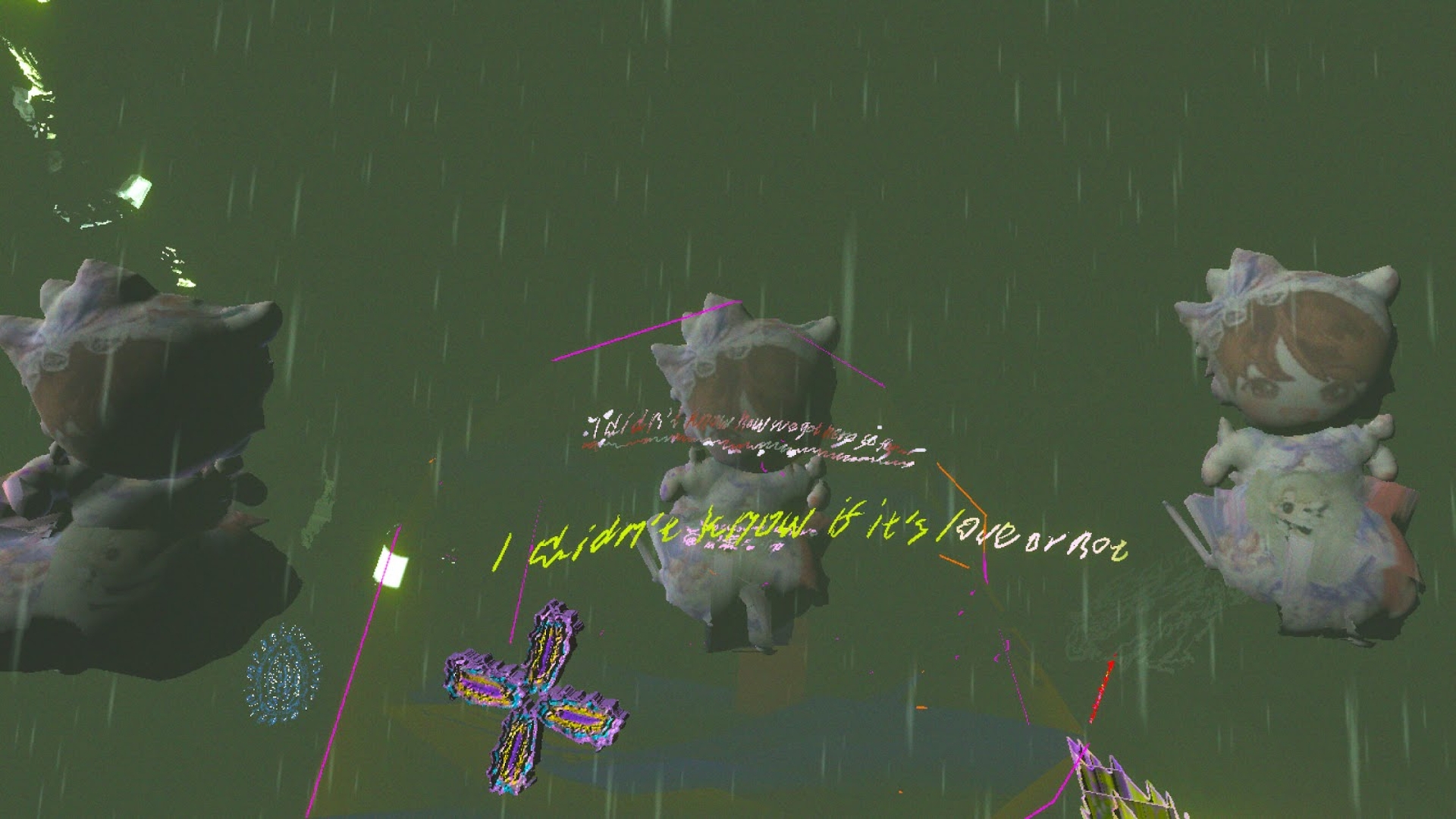

Pete Jiadong Qiang, Queer Maximalism HyperBody (2020). Game level Pinkray, Pinkray plush dolls, VR gameplay screenshot. Courtesy of the artist and CheeseTalk.

The latest in a series of interviews with artists who have a significant body of work that makes use of or responds to network culture and digital technologies.

Banyi Huang: I love the conceptual framework you’ve developed around gamespace, architectural space, and online fandom as they intersect with queer identity: it’s speculative, but it’s also personal and tender. Your VR game Queer Maximalism HyperBody, for me, is a performative declaration of being unapologetically queer, maximalist, and body-centric.

It makes me think of scholar Yuk Hui’s definition of cosmotechnics as the unification between cosmic order and moral order through technical activities, which has been instrumental in conceptualizing a non-Western philosophy of technology. Can you talk about how you developed your framework of game fandom as a form of cosmotechnics?

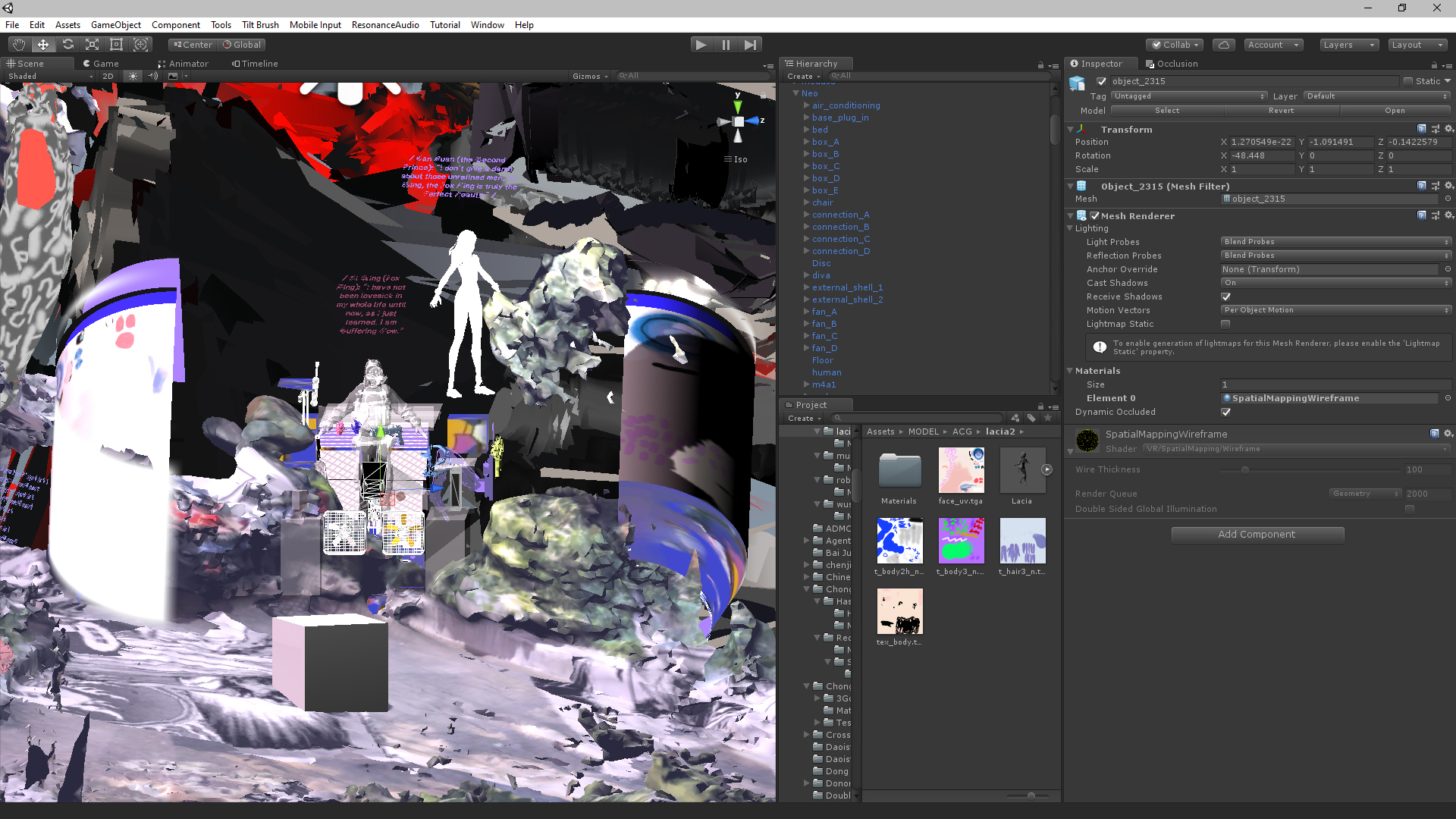

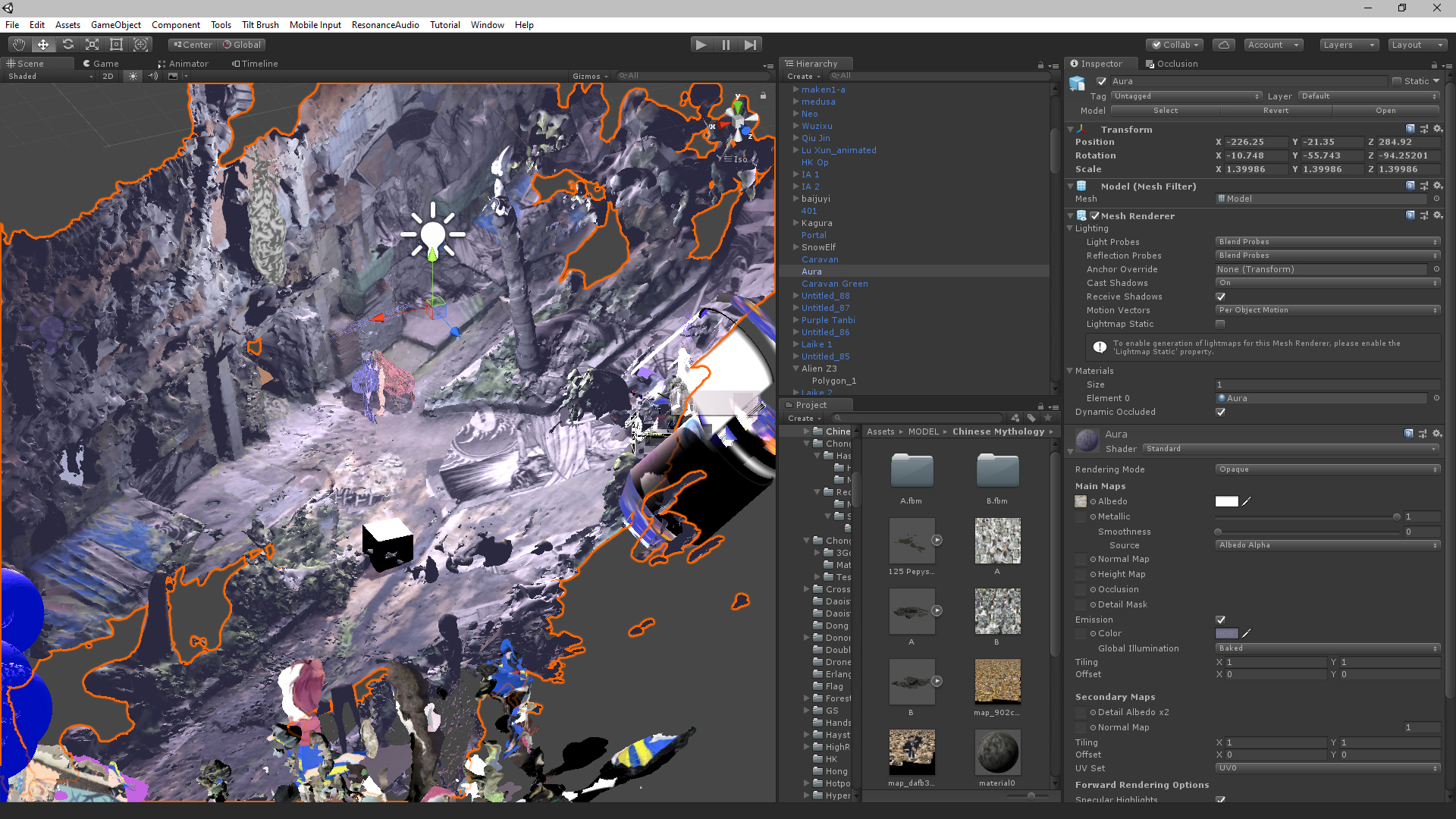

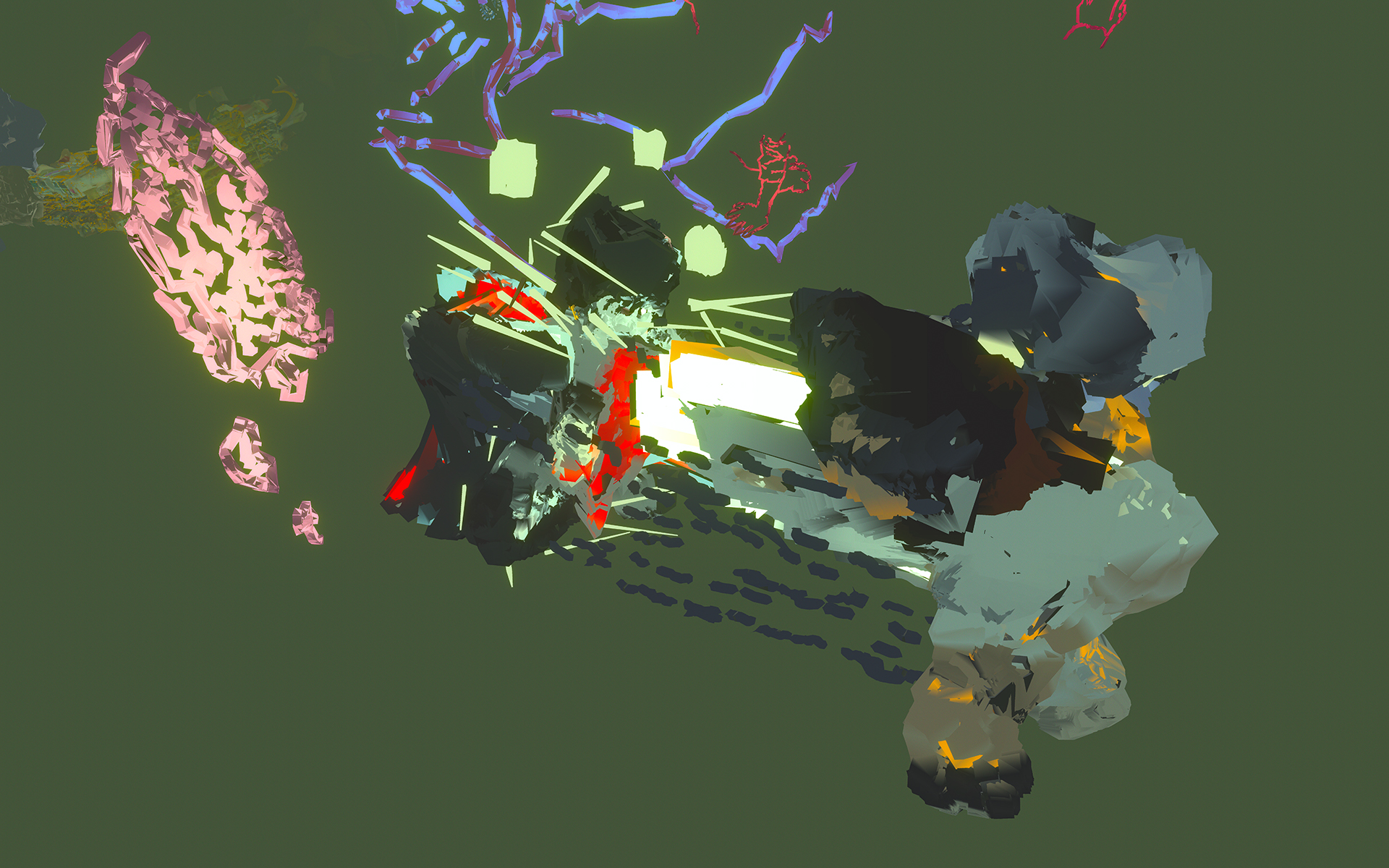

Pete Jiadong Qiang, Queer Maximalism HyperBody (2020). Game level Pinkray, Making the mod of Parallel Neo Home in the cosmotechnics of multi-fandoms, Isometric screenshot of Unity editor of the VR game.

Pete Jiadong Qiang: I regard developing my VR game Queer Maximalism HyperBody as an architectural practice. When I was at the Architectural Association School of Architecture (AA) in London, I was heavily influenced by my tutors David Greene and Samantha Hardingham, and visiting tutor and artist John Walter taught me how to negotiate architectural-pictorial space with a maximalist approach. Since my architectural project Health Aficionado Experimentation (HAEXP), I started to test the intermediations between pictorial space, architectural space, and gamespace through animation, exploring a physical-virtual space that is incomplete, imperfect, and picturesque. This speculative and experimental architectural approach allows me to design and make from the perspective of an acafan (an academic who identifies as a fan).

For HAEXP, I did a digital anthropological study in World of Warcraft as a female Night Elf druid, and studied forms and animations from druid shapeshifting. I then remixed sounds from Dota 2 and StarCraft into my animation. With a fluid and amateur approach, I hope to bridge the gap between the academic and personal. At the AA, I was always asked things like: What are the speed, time, and interval of your architecture? How much does your architecture weigh? Is your architecture designed only for humans but not horses or cows? Through my experimental architectural practice, I think about how I can design a physical-virtual space with a soft, feminized aesthetic that encompasses human and nonhuman, built environment and natural, agricultural and urban, civil and technological. During the graduation ceremony at the AA in 2016, David suggested, “Pete, why don’t you do something inside VR next?”

Shifting from speculative and experimental design to a practice-based PhD, I audited Hui’s philosophy course at the City University of Hong Kong in 2021. As a Chinese acafan, I think Hui’s ideas around cosmotechnics are very helpful to rethink the technics/technologies behind ACGN (anime, comic, game, and novel) fandoms and communities in mainland China, particularly when dealing with game engines and VR devices. For example, I studied a Chinese BL (Boys’ Love) cultivation novel with my friends Tianqi and Linn titled C Programming Language Cultivating Immortals by Yi Shi Si Zhou, in which the technological and mythical events and male/male character pairings are entangled between C programming and Daoist cultivation, as China and the West engage in a technological and affective conversation during the development of a VR world system. I was interested in the way the main character cultivates immortality by programming himself through infinite loops, object-oriented programming, and networks constantly shifting between real-life and VR environments.

Based on my interviews and collaborations with various fandom members, I generate sounds, texts, 3D paintings, body characters, 3D scanned environments, and architectural mods in the VR gamespace. I always seek to create a multi-fandom cosmotechnics intermediated between culture, technology, and affection.

Pete Jiadong Qiang, HAEXP (Health Aficionado Experimentation) (2016). Making the life-size architectural drawing, Screenshot of animation.

BH: As my diasporic sentiment grew, I have grown to appreciate the Xianxia 仙侠 or cultivation genre. Xianxia is a genre of Chinese fantasy heavily inspired by Daoism, referencing Chinese mythology, folklore, Chinese medicine, and other aspects of a larger system of cosmotechnics; characters usually revolve around “cultivators” who seek to become immortal beings by cultivating Qi. Science fiction writing that taps into the Xianxia fantasy genre can be so arresting—for example, Liu Cixin’s VR game that advances through stages of civilization and technological and scientific discovery, or Xia Jia’s A Hundred Ghost Parade, where immortal monsters are revealed to be AI-powered robots.

For me, the potential for worlding unites Xianxia and science fiction: they are interested in collectively bringing forth something that does not yet exist. It resonates with what Jose Esteban Munoz calls queer futurity—a warm horizon imbued with potentiality. Against the normative, territorializing forces of the metaverse worlding, what does queer worlding mean for you? And how does that manifest in your work?

PJQ: During my research into Chinese BL novels, I was addicted to everything related to Daoist cultivation. BL novels are really inclusive and fluid in blending with any possible genres. Notions of myth, technics, and technology in Chinese science fiction, fantasy and specifically immortality-cultivation texts provide me with down-to-earth materials to fantasize a worlding of multi-fandom cosmotechnics. For example, for my VR game Queer Maximalism HyperBody, I engaged in digital ethnography and autoethnography with many interviewees and collaborators. I interviewed fandom member Emma on her male/male shipping videos of Pinkray/Katto within the real-life C-Pop boys group ONER; I collaborated with my friends Tianqi and Linn to investigate the Chinese BL novel context; and I worked with my architectural fellows Jingzhi and Aristo to modify their architectural projects in VR gamespace. I also had conversations with another fandom member CheeseTalk on her fanart depicting a male/male ship1 between characters Luo Ji and Shi Qiang in Liu Cixin’s The Dark Forest, the sequel to the acclaimed sci-fi novel, The Three-Body Problem. Concurrently, I interviewed my friend, Chinese female science fiction writer Tang Fei, and modified her novels into a visual novel game level called "HyperBody: Seventeen/Sixty-One" within Queer Maximalism HyperBody. Through iterative conversations and collaborative practices in the VR game, a worlding of cosmotechnic multi-fandoms is established in the VR gamespace.

Pete Jiadong Qiang, Queer Maximalism HyperBody (2020). Game level Pinkray, Worlding of cosmotechnics of multi-fandoms, Isometric screenshot of Unity editor of the VR game. Courtesy of the Artist and Emma, Tianqi, Linn, Jingzhi, Aristo, and CheeseTalk.

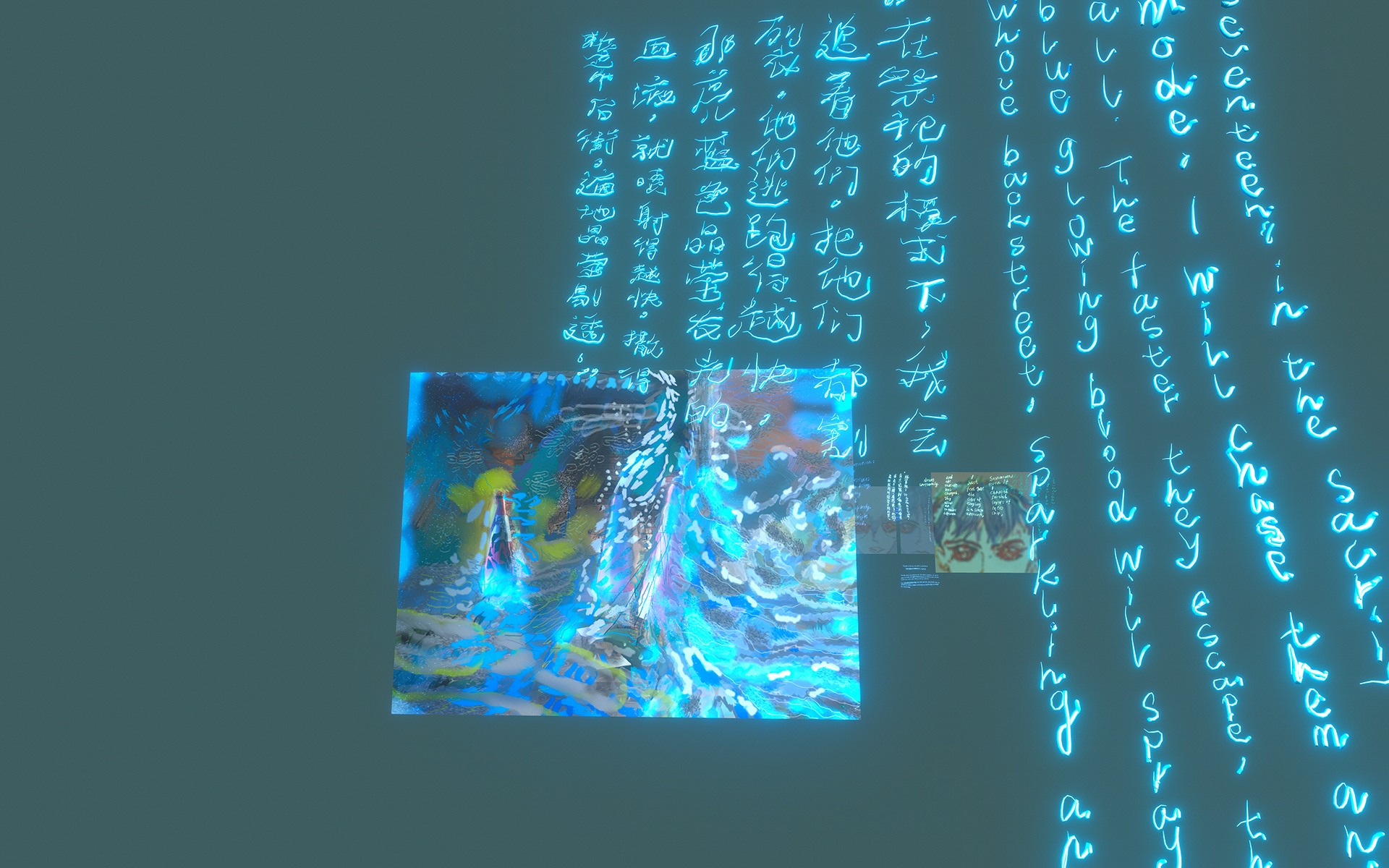

Pete Jiadong Qiang, Queer Maximalism HyperBody (2020). Game level Seventeen/Sixty-One, screenshot of VR game. Courtesy of the Artist and Tang Fei.

BH: Combined with state censorship and consumerism, the Chinese online fandom community is highly politicized and is a hotbed for both mass mobilization and control. I find that fandom practices like modding (making user-determined enhancements), crossover (bridging characters from different fictional words), and shipping (desiring romantic connection between fictional characters) are imbued with radical, liberating potentials. They bring about connections that don’t yet exist, mixing genres and creating new ones. The Untamed (a Chinese fantasy TV series based on Boys' Love novel Mo Dao Zu Shi) and its fandom was what got me through the start of the pandemic. For a period of time, I was consumed by the love and yearning between the main characters, who are beautiful men, and obsessed over the shipping of the actors themselves, scrutinizing their every interaction for signs of affection. I’m curious about how you approach and incorporate fan-generated content. Do you see it as inherently queer and transformative?

PJQ: I’m indifferent to famous fandoms like The Untamed; I tend to look for small and minor communities in which you might be able to experience their fan dynamics and the triangulation between culture, technology, and affection without too much politics and volatile censorship. With the Pinkray/Katto shipping in C-Pop boys group ONER, Emma helped me dive into the “posthumous” communities (In the fandom, if a ship or character pair has a bad end, the dedicated shipping community is announced dead and archived) with less politics and censorship and substantially explore the fandom’s archives to understand the narrative behind their practices. For the Luo Ji/Shi Qiang ship in Liu Cixin’s The Dark Forest, CheeseTalk approached me first because we met at my VR game workshop at Goldsmiths and she really liked my VR gamespace.

Both Emma and CheeseTalk are Chinese and belong to Generation Z. Because they are so young and feel passionate about remixing characters, personas, and affections, they can envision creative and alternative affect-assets within their shipping practices. For Pinkray/Katto and Luo Ji/Shi Qiang, they share sincere feelings in both their real-life and fictional relationships. For Emma and CheeseTalk, the more important part is how to blur and remix both physical and virtual personas to create new, genderfluid combinations. They also hope to share their ships with the general public on mainstream online platforms like Weibo and LOFTER (a Chinese microblogging platform for fanart). I think it might be a matter of what I call queer tuning—a soft, passive way to seek healing regarding identity, gender, and sexuality without a conscious structure of resistance. Most mainland Chinese fandoms retain a young constituency without too many historical, cultural, political, and moral burdens. Just like how the sea receives all rivers flowing into it, the tuning of fandom expects and welcomes new cultural, technological and affective turns.

Pete Jiadong Qiang, Queer Maximalism HyperBody (2020). Game level Pinkray, Pinkray plush dolls, VR gameplay screenshot. Courtesy of the artist and CheeseTalk.

Pete Jiadong Qiang, Queer Maximalism HyperBody (2020). Game level Pinkray, Pinkray plush dolls, VR gameplay screenshot. Courtesy of the artist and CheeseTalk.

Pete Jiadong Qiang, Queer Maximalism HyperBody (2020). Game level Pinkray, Luo Ji/Shi Qiang ship, screenshot of VR game. Courtesy of the artist and CheeseTalk.

Pete Jiadong Qiang, Queer Maximalism HyperBody (2020). Game level Pinkray, Luo Ji/Shi Qiang ship, screenshot of VR game. Courtesy of the artist and CheeseTalk.

BH: Over our WeChat conversation, you talked about your background in architecture, and how that training makes you think in environmental terms; coming from art history, I tend to think in a more artifact and object-driven way, and I find that difference very interesting. In one of the public events for World on A Wire, an online and in-person exhibition presented by Rhizome and Hyundai, Michael Connor pointed out that you employ gestural painting as a visual strategy in building digital space. The gesture declares the presence of the body and its messiness. In Dungeon: Maximalism HyperBody (2021), cascading AR texts that bear in traces of your handwriting float on top of geometric planes, and meshes with handpainted textures exist alongside 3D scans of physical archives you have worked in. Can you talk more about your process with visual strategies when you are building VR gamespace? How do the environmental and the gestural relate to one another?

PJQ: Back to my architectural project HAEXP at the AA, I was very lucky to borrow Bruce McLean’s studio in Ealing, West London to paint an 26.2 feet by 8.2 feet architectural drawing on the back of poster papers with pencil, watercolor, crayon, and acrylic. Between pictorial and architectural space, I love to test the notions of body, form, aesthetics, and scale. After getting into VR practices, I continued to paint with software like Tilt Brush, Quill, and Gravity Sketch. For physical installation, I use the foaming agent to negotiate the form and aesthetic of VR paintings in physical space.

When painting in VR, I engage with the negative spaces and voids between brushes, meshes, textures, and materials. Painting within such a non-collision space, I question the limits and bounds of bodies, embodiments, and objects, which are constantly reconfiguring. Through painting, I develop the methods of modding, crossover, and shipping (character pairing) to try to create an affective cosmotechnics of multi-fandoms. As an architectural maximalist, I think my Queer Maximalism Manifesto for the Hypertired in 2019 can be a starting point to interrogate bodies, 3D paintings, 3D scans, and architectures.

BH: Project Search (繼續追尋) is a recent visual novel game that you have been working on. Can you talk more about how it came about, and what direction you want to take it in?

PJQ: Project Search is technically a series of scenes and rooms based on Mozilla Hubs. Unlike my VR game, the Mozilla Hub version is lightweight, multi-player, and you can play it from most PCs and laptops. The game was made in Linhai, a county-level city in Taizhou, Zhejiang Province, in southeastern China. It came out of practice-based research conducted at an art residency initiated by With in/out Linhai, a cultural group supported by the local government and the China Academy of Art. From site analysis, cultivation novel writing, 3D scanning, and scene design, I created a cultivation gamespace in the context of Linhai to allow local residents, tourists, students, and researchers to reconsider the Daoist culture of cultivation and potential re-materializations of physical and virtual space.

Although the story of this visual novel game is original compared to my multi-fandom works, it tinkers with my personal experiences of eating traditional food, browsing old districts, and meeting Daoist cultivators in Linhai. My imagination of this technology-cultivation story remixes the narrative in Chen Kuo-fu’s film Double Vision (2002), which I love a lot! On the other hand, I tried to prioritize sound work first in Project Search instead of visuals. Under the current COVID policy in mainland China, Project Search’s physical installations were delayed by four months. It was finally exhibited by the end of September this year in Linhai. The installation, located in a derelict 1950s worker’s club, is made with site-specific materials and pays tribute to a new Hong Kong film Drifting (2021). Emphasizing a real-life urban context, Project Search tried to establish a unique online/offline community by developing an audio-visual gamespace, in order to re-materialize cultivation, technology, and affect.

Pete Jiadong Qiang, Project Search (2022).Game scene Syncing, Gameplay screenshot. Courtesy of the artist and With in/out Linhai.

Pete Jiadong Qiang, Project Search (2022).Game scene Syncing, Gameplay screenshot. Courtesy of the artist and With in/out Linhai.

Pete Jiadong Qiang, Project Search (2022). Game scene Syncing, Mixed media installation: plastic sheet, spray foam, paint, dodecahedron mold, bean bag chair inner liner, audio cassette player, tapes and computer, Dimension variable, Linhai.Courtesy of the artist, Fengyuan Tian, Ziyi Xu, Yurui Dong, and With in/out Linhai.

Pete Jiadong Qiang, Project Search (2022). Game scene Syncing, Mixed media installation: plastic sheet, spray foam, paint, dodecahedron mold, bean bag chair inner liner, audio cassette player, tapes and computer, Dimension variable, Linhai.Courtesy of the artist, Fengyuan Tian, Ziyi Xu, Yurui Dong, and With in/out Linhai.

Age: 31

Location: Exeter, Devon, UK

How, and when did you begin working creatively with technology?

I was addicted to Britpop in high school and started to make and design an alternative rock BBS. I also made a fanzine as an EXE for free download in my BBS.

What did you study at school or elsewhere?

I studied AA Diploma (ARB/RIBA Part 2) in the Architectural Association School of Architecture (AA).

What do you do for a living or what occupations have you helped previously?

I am currently working as a virtual space curator at X Museum.

What does your desktop or workspace look like? (Pics or screenshots please!)

Screenshot of Pete's Desktop, 2022, Courtesy of the artist.

Screenshot of Pete's Desktop, 2022, Courtesy of the artist.

Photograph of Pete's workspace, 2022, Courtesy of the artist.

Photograph of Pete's workspace, 2022, Courtesy of the artist.

______________

1In fan communities, "shipping,"(which is derived from "Relationship") refers to the wish that 2 or more characters will enter a romantic or sexual relationship.