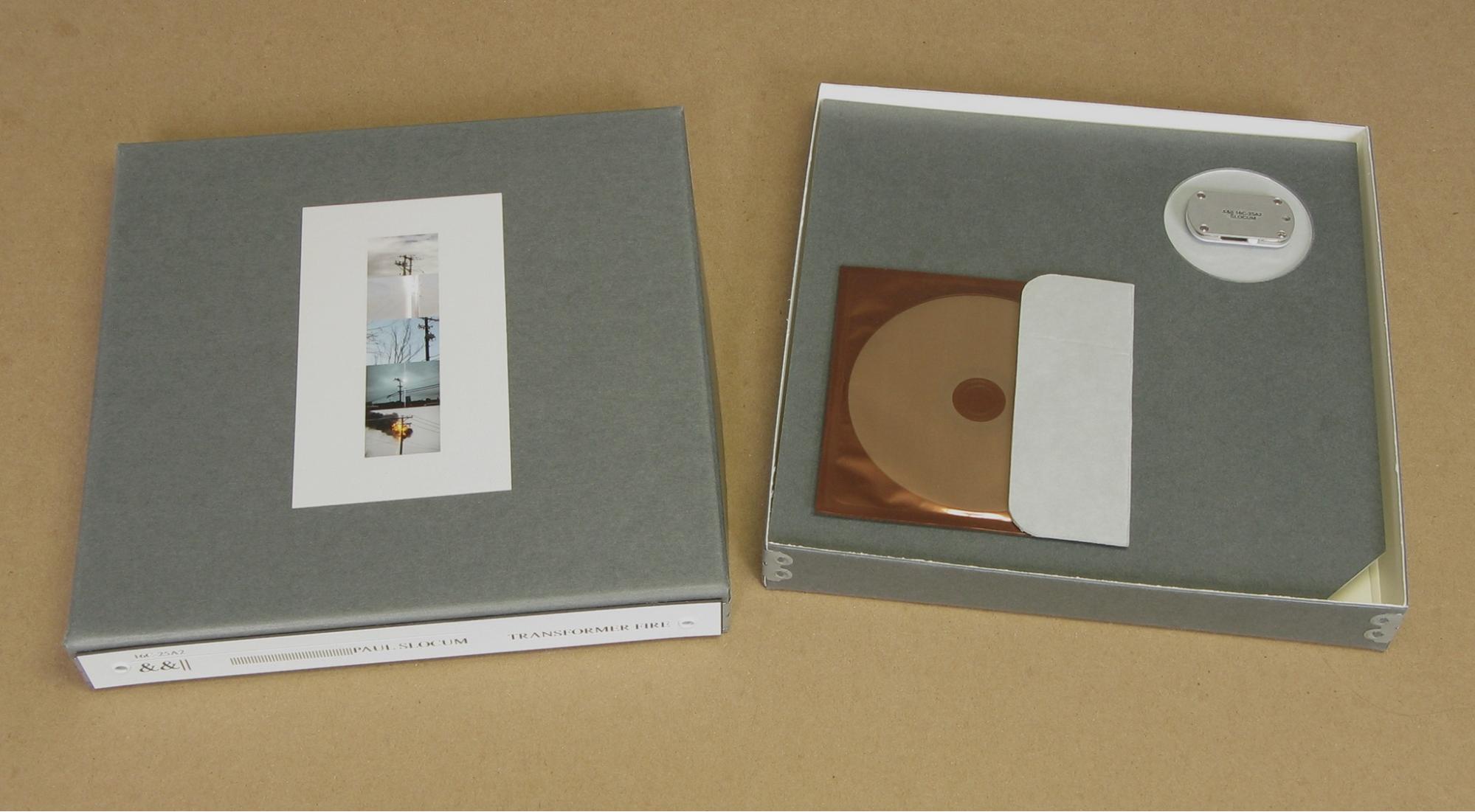

Paul Slocum, Transformer Fire (2008)

For its blockbuster sale of Beeple’s Everydays: The First 5000 Days, an artwork in the form of an NFT and a digital file comprising thousands of images, Christie’s auction house published an essay including the following dubious claim:

Digital art has an established history dating back to the 1960s. But the ease of duplication traditionally made it near-impossible to assign provenance and value to the medium.

There are quite interesting reasons for artists to explore the use of NFTs, and, clearly, they currently offer a new form of support. But, among other issues, the argument that NFTs have “solved” a long-standing problem of uniqueness and provenance in digital art ignores the fact that they rely on forms of trust and negotiation and authentication that aren’t starkly different from a longer history of digital art markets. Even with NFTs, questions arise, such as: who actually authorized the minting of a work? What license is attached to it? How can this license be accessed? What happens if it needs to be changed? These questions point to the some of the challenges that have always faced digital art markets, and are not fully solved by standalone blockchain solutions, all of which points to the need for ongoing care and stewardship with or without the NFT.

This moment is certainly unique; there has never been this kind of speculative money in digital art, and the NFT as an addressable online space for code and content represents new affordances for digital media and ways of relating online. Still, it’s important not to lose sight of the long history of experimentation with the sale of digital work, and with using market structures as sites for creativity, even without the NFT or the blockchain. Rhizome itself even spawned a for-profit startup, StockObjects, which launched in spring 1997 with a library of artist-made graphics and animations available for licensed use.

Prompted in part by a tweet from curator and NFT art advisor Ché Zara Blomfield, I’ve spent the past few days reaching out to digital art sellers and compiling old interviews to offer some helpful points of comparison for the ongoing market craze. It’s an inexhaustive list, intended only as a reminder of some of what has gone before, and to suggest that the commercial success of digital art in the present day is less surprising than it is long overdue.

The Thing BBS

Peter Halley, Superdream Mutation, 1993.

In the early 1990s, a community of artists, writers, psychoanalysts, and cultural gadflies came together around The Thing, a bulletin board system (BBS) in New York that expanded to include nodes in several European cities. (Rhizome recently completed a partial reconstruction of materials from The Thing should you like to learn more.) Constantly experimenting with alternative forms of community and distribution, The Thing included early digital art exhibitions and sales, including a notable work by Peter Halley.

In a talk on The Thing for The Influencers festival, Wolfgang Staehle described the community’s experimentation with the exhibition and sale of digital work:

[I knew] Peter Halley, a painter, and the interesting thing is, if you look at his paintings at the time, they all look like electronic circuits or something... He did this piece for me in Photoshop one day. We decided we’d sell it for $20, the price of a common CD or something. It wouldn't be signed, but whoever bought it would be entered in a database, like an honor system. You can, of course, give it away or distribute it afterwards, but only the ones that are in the database are the ones that supported this project and are the real patrons.

It worked, we sold 16. We sold 16 for $20 each, and the funny thing is, as a Danish magazine had a deadline and they wanted to print it and talk about this and write about it, so they had to call from Denmark, by phone, into our Manhattan local number, international call, at whatever speed they had. 19 kilobits or whatever. This is almost a megabyte or something.

It took them over an hour. They paid $150 for the phone call, and $20 for the piece.

Postmasters Gallery

Postmasters was founded by Magda Sawon and Tamas Banovich in 1984, and is currently operated in Tribeca. The gallery, which in the past served as headquarters for The Thing and Rhizome, has been working with digital art since 1991, when they showed Mark Madel’s networked objects. There are no extant images of that show, but their 1996 exhibition “Can you digit?” was sort of a watershed moment for the exhibition and sale of digital work in NYC. For that exhibition, they sold artists’ works on floppy disk.

For all digital works, they typically offer a certificate of authenticity, with copyright retained by the artist, and they try to track provenance on behalf of their artists. But as Sawon notes, “the secondary market for media as you must know was next to non-existent before NFT burst. I had several collectors donating the works to museums, that’s all.”

As well as selling purely digital work, Postmasters artists also present digital works in a physical form, such as the database objects by Jennifer and Kevin McCoy (one of which is on display at the Met now, featuring a suitcase and screen and player). These solve many of the problems of digital art sales by treating them more as traditional art objects.

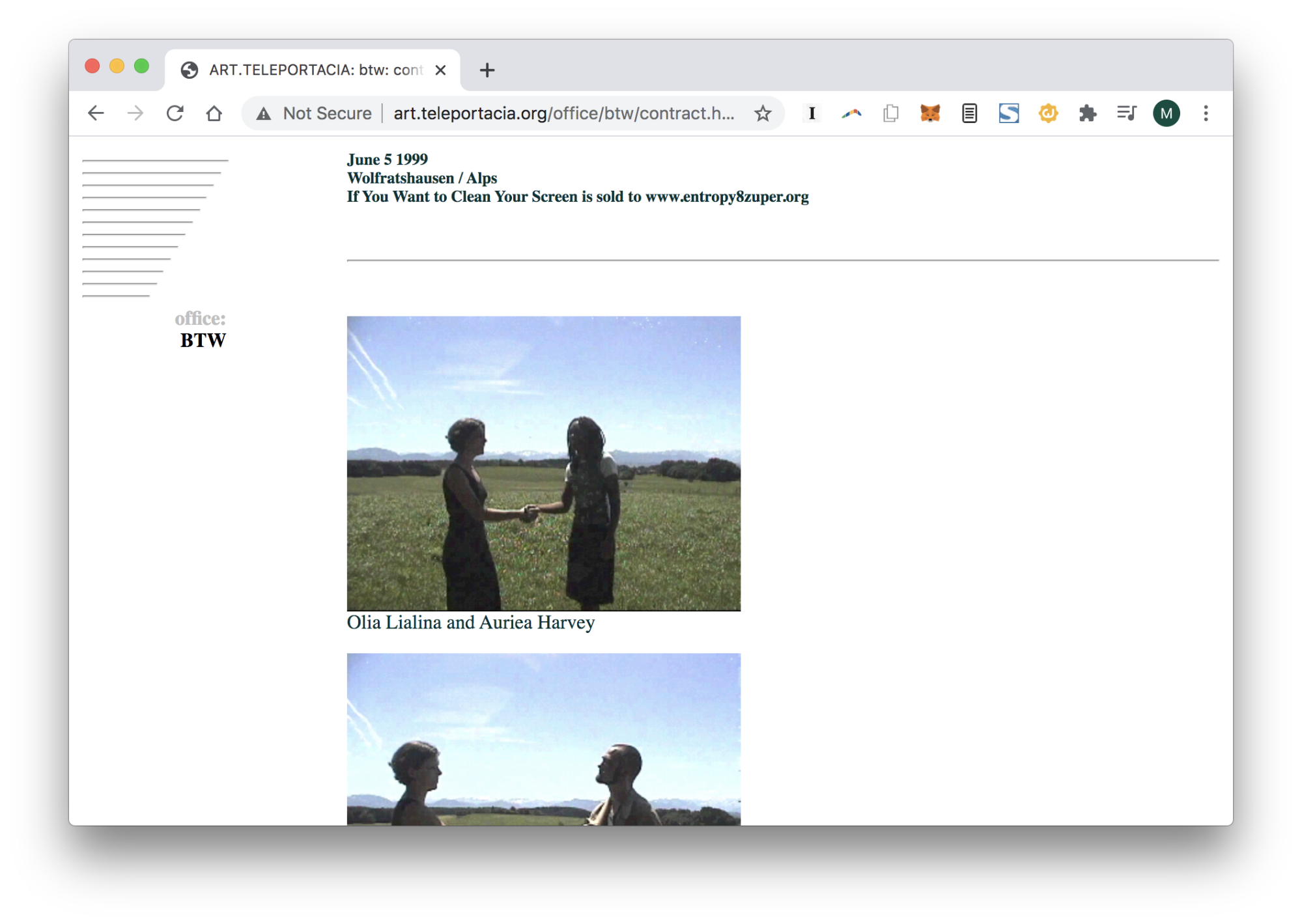

First Real Net Art Gallery

Artist Olia Lialina established the self-proclaimed First Real Net Art Gallery, Art Teleportacia, in 1998. She wrote the following about the project in a Russian magazine in 2000:

What if instead of exporting artworks and ideas into the offline world, we tried to import the artist-gallery-audience dynamic online, together with any monetary exchanges that might flow out of it?

That’s when the First Real Net Art Gallery, named Art.Teleportacia (art.teleportacia.org), came into being. It’s a place online (currently, one of several; two years ago, the principal one) where you can buy pieces of net art to decorate your electronic office or home page. Business people buy paintings to decorate their offices—why wouldn’t they consider embellishing their representative pages on the global network? Such was my logic back in July 1998.

I used the ambitious “First Real” prefix to once and forever separate this gallery from thousands of other Net Art Galleries, named this way ages ago but containing something completely opposite to true net art. Usually, these galleries feature official and private pages of painters, photographers, woodcutters, etc. They publish photographs of their art, using the web to the full extent as an electronic catalogue. I won’t be surprised to find out that some people out there still consider this kind of presentation material “net art.”

The gallery opened with an exhibition called “Miniatures of Heroic Period.” It featured small-scale artworks by five [Real Net Artists], each accompanied by a specially commissioned article written by a net art critic. The critics, who were used to writing about how being not for sale was in the very nature of net art, had this time to explain why this or that piece could become a perfect investment and a source of collector’s pride.

To this day, Art.Teleportacia haven’t yet become the “money machine”. In a year after its opening, I’ve only managed to sell one piece of art—unfortunately, it was one of my own. And since it was bought by a friendly site, entropy8zuper.org, I took it (perhaps unjustly) as a purely artistic gesture.

Neen

Neen was an art movement founded by Miltos Manetas and Mai Ueda in 2000. “Neensters”—Manetas’s internationally dispersed disciples—produced “single-serving” websites, mounted exhibitions in Los Angeles and Milan, (almost) staged interventions in New York City, and collaborated on numerous other projects. The movement was included as a work in Rhizome’s Net Art Anthology initiative.

Manetas, writing in 2002, argued that websites were a collector-friendly art form, centered around the DNS system, which tracks ownership of named spaces on the web:

A work of art, comes to the World, because of its creator, but it survives only because of the collector who will take care of it. In terms of Neen, a collector, is even more important than the artist [themselves], because [they] "do" art with less effort.

Collecting is the power to decide if a piece should continue to exist or not: once you own it, you can decide if destroy or conserve it.

Never this power has been more significant, than for a collector of websites: if [they] will not pay the hosting fee, the work will disappear. The name of the website will return to the pool of the available domain names. The whole piece will expire as it has never existed.

bitforms gallery

Founded in 2001 by Steven Sacks, bitforms gallery represents established, mid-career, and emerging artists critically engaged with new technologies. Here's Sacks on the gallery's work:

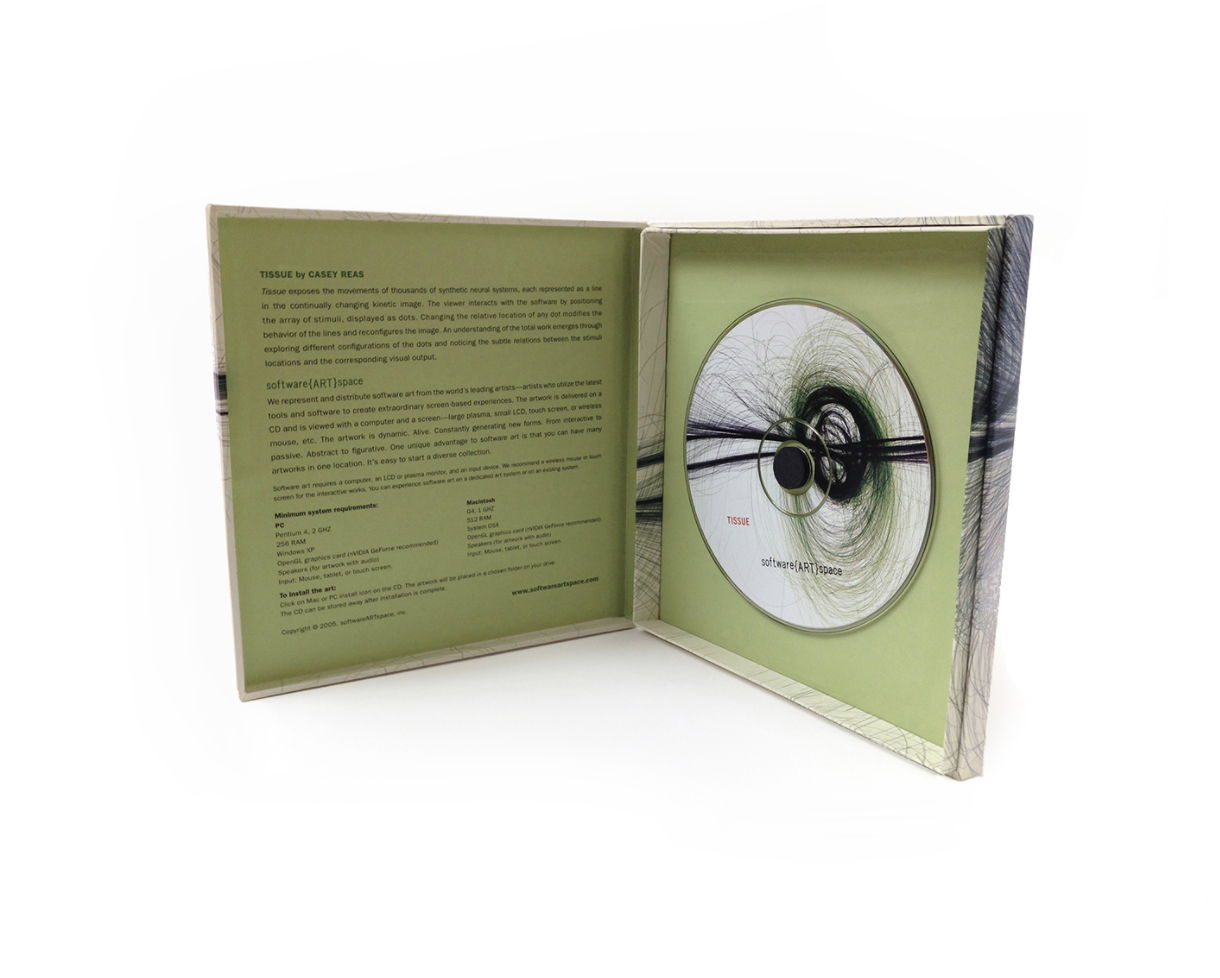

The inspiration for the gallery were the plethora of museum shows focusing on media arts in 2000-01, including bitstreams at the Whitney, 010101 at SFMoMA and Digital printmaking at the Brooklyn Museum. Other than PostMasters, there wasn’t a commercial gallery that had a deep connection to experimental media art and culture.

From the beginning it was important for the gallery to have a historical perspective, exhibiting media artists from different generations. Revealing the evolution of media tools and cultural changes that impacted the artist’s practice. Working with artists that created physical pieces and installations that referenced the digital process helped the gallery reach a wider audience of collectors who may have been apprehensive acquiring pure digital artworks.

We experimented with a few concepts over the years, like Mark Napier’s Waiting Room in 2002, a web-based works that we sold as shares delivered on a CD ROM with a signed certificate. Collectors paid $1000 a share (50 total) to gain access to a website where they could collaborate on a single online canvas. We sold around 10 of them. This inspired Software Art Space, where we custom packaged and sold CD’s of software artworks in editions of 100 for $100 each. At the time software art was just gaining traction and we felt this was a way to introduce this genre to a wider collecting audience. This led to the gallery working with many software driven artists such as Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Siebren Versteeg, Manfred Mohr, Marina Zurkow and Casey Reas who use code to create and present their works. Other historically relevant artists like Beryl Korot used code as a conceptual influence through weaving and video installations.

Today, the gallery spans the rich history of media art through its current developments, offering an incisive perspective on the fields of digital, internet, time-based and new media art forms.

And/Or Gallery

Paul Slocum and Lauren Gray founded And/Or Gallery in Dallas in 2006 focusing on digital and electronic media. Nearly from the outset, the gallery became known as an early champion of Postinternet art, including an early exhibition by Kev Bewersdorf and Guthrie Lonergan, and its program included aspects of broader internet culture such as memes. And/Or later relocated to Pasadena, California, and is scheduled to reopen in April. It also offers a multichannel media player module that makes it easier for artists and collectors to display video and image artworks.

Slocum recently wrote on social media,

In 2008 And/Or Gallery sold the first editions of ‘Landscape 05-15-05’ and VVEBCAM by Petra Cortright — a JPEG that was publicly available on Petra’s website and a video on her Youtube page. For 15 years And/Or has been producing professionally conserved digital editions that are the same as NFTs for legal and conceptual purposes, except that we use our own database and some come with an archival media box. Unlike many digital editions, ours are fully legally compatible with museum collections as the certificates explicitly permit public display. Our physical prints also include the original file and a certificate that allows reprinting in the case of loss or damage. It includes copies of the work on two DVD-ROMs and two USB drives, plus a certificate.

Website Sales Contract

Artist Rafael Rozendaal was a participant in the original Neen movement, and has continued to explore the website as art form ever since. His publicly available Art Website Sales Contract continues to be of practical use for artists selling digital work. Read more about Rafael’s work in this 2013 Rhizome article.

On his website, Rozendaal describes the contract as follows:

The Art Website Sales Contract is a document I created in 2011. I use it when I sell one of my art websites. The document is both the certificate of authenticty, and a legally binding document between the artist and the art collector. Selling websites as art pieces is still very new, and I hope this document can help any artist who want to sell their art this way.

I think selling a moving image in a domain name is an elegant solution: the work is available to the public, and the ownership is unique, because domain names are unique.

I recently revised the text of the contract together with Steve Turner, my gallerist in LA. We simplified the document, keeping the original ideas but making the text more straight forward.

The document is free to download.

left gallery

left gallery was founded by Harm van den Dorpel and Paloma Rodríguez Carrington in 2015, and offers digital file formats such as .exe, .saver, .mp4, .html, .gif, .txt, .rtf, and .m3u for sale via cryptocurrency and credit card. left gallery was profiled on Rhizome in 2018.

van den Dorpel recently wrote “Tokenizing Sustainability,” a piece about his own experience with cryptocurrency, and how it informs his view of ongoing developments in the NFT space. He writes,

We would sell "downloadable objects'' in large editions for low prices. Customers could pay with crypto, PayPal, or credit card, and, after purchase, we would manually transfer the token belonging to their purchase to those clients interested in having them – most didn't understand what a blockchain was at all.

Although the token provenance information that ascribe stored on the immutable Bitcoin blockchain will always remain there, in practice, we have lost access to it, as their web interface to retrieve it was discontinued. So, in 2018, I bit the bullet and deployed my first ERC721 smart contract and I minted Ethereum tokens for the editions that had been sold. I asked owners to send me their Ethereum wallet address in order to transfer them the tokens for the editions they owned. This was, in itself, an "interesting" situation, because this meant that some editions were now tokenized on two blockchains at once.

To my disappointment, when I announced this new Ethereum website integration, few buyers actually requested the token belonging to their purchase. Sales on left gallery continued, but interest in ERC721 tokens kept declining among our clientele. At the same time, the transaction costs kept increasing, to a degree where the costs for minting and transferring tokens exceeded the sales price of the actual artworks by orders of magnitude.

Paddles ON!

In 2013, Phillips auction house partnered with Tumblr and curator Lindsay Howard to present Paddles ON!, a groundbreaking auction and exhibition that brought together artists who were “using digital technologies to establish the next generation of contemporary art.” The project included twenty artists, of whom only six had gallery representation, and included both screen-based work and physical objects involving digital elements. The sales totaled $90,600 with 20% of the proceeds benefiting Rhizome. The event’s success led to a second edition in London in 2014 benefiting Arcadia Missa.

In an interview with Complex, Howard described her approach to bridging the gap between the contemporary art market and digital culture:

Digital technology is just another tool, but it’s been really interesting as we’re integrating it with Phillips, their lawyers, their art handlers, their collectors, and their specialists, to see it from this other perspective of people who have extensive expertise in contemporary art. For them, digital art is whole new terrain. We’ve rewritten Phillips’ contract multiple times, which has been really exciting because it needed to reflect the openness, transparency, and access—all these values that are really important to this generation.

Some people have asked me, "How did you package these works for an auction house?" We didn’t package them at all! We’re just remaining true to the artists’ intentions.

For the animated GIFs and videos, the collector will receive a USB drive with those files on them or a Mac Mini with the files on them. We wanted to keep the costs down for the auction and keep everything below $20,000, so we’re not including any of the hardware. But some galleries will sell you the whole monitor, which is really great and convenient.

One of our goals at the beginning was—what if we could bridge the tech and startup communities with digital art? These are people who really understand this work on a whole other level, and they’re people who are already think that renewing a domain name is peanuts. One of our goals was to connect that field with digital art and potentially create some kind of alignment there for collectorship, patronage, and support, because the digital work really needs that.

Transfer Gallery

LaTurbo Avedon 'New York Formation' (2013) Digital File and Direct Print on DiBond. Edition 25 + 2AP. Courtesy the artist and Transfer Gallery.

TRANSFER was co-founded in Brooklyn in 2013 by Kelani Nichole, and is currently based in Los Angeles, with programs happening in physical space and online. Via email, Nichole shared some background on the gallery’s approach to the sale of digital work:

Most of the sales at TRANSFER are digital files – file types we've placed include Animated GIFs, Videos, Algorithmic Art, Software, Video Games, HTML artworks, Virtual Reality and Augmented Reality. Almost always there is an installation component specified for the digital works. We also sell 3D printed sculpture and mounted prints from digital files, and these sales often include the digital files themselves.

There is always at the very least a package including media carriers, printed certificate of authenticity, and rights & obligations for the buyer, exhibition instructions, and additional conservation materials. Often an artist will produce custom packaging for these artifacts. There's also frequently hardware or installation components provided as part of the work. Images are sometimes produced as prints or mounted objects, along with the digital files and instructions for how to have them re-produced for restoration purposes.

TRANSFER's third exhibition after opening the gallery in 2013 placed a number of animated GIFs from Lorna Mills with an important private collection in Belgium. One of the works was a multi-channel GIF installation provided on digital photo frames, along with media carriers with the original files, and extensive documentation, as mentioned above. Our next exhibition the following month was a solo show with LaTurbo Avedon called 'New Sculpt' and we experimented with a larger edition of a digital file that was priced and sold only in bitcoin. Collectors received a thumb drive with the file along with the print on di-bond. We had a Mt.Gox button for sales! You can still see this edition on our website: http://transfergallery.com/laturbo-avedon-new-sculpt/

The gallery does a ton of work to develop certificates, contracts, terms, exhibition instructions, care instructions, and other supporting documentation, which can include more usage and rights depending on if a work needs to be maintained annually, updated regularly, or migrated to a new hardware platform. We work closely with our studios to make sure that we are offering meaningful delivery to collectors, in a way that resonates with the work. Much of what we've sold is also available online, in some format, for free. This is something TRANSFER has always truly believed in – the value of open work – so it's pretty amazing to see a similar set of values arrive en masse with the explosion of NFTs.

panke.gallery

Founded in 2016, panke.gallery seeks to open up a local and international dialogue between established and emerging artists. The presented works derive from the connection between digital or net-based art and club culture, reflecting in particular the recent history of Berlin. panke.gallery’s founder, Sakrowski, shared the space’s approach to digital art sales via email:

I have to smile a bit ;) because now everyone thinks about [sales of digital art] in the mists of the NFT hype (me totally included)… but, shouldn’t we work all together on it, so that we all could fair and easy share the revenue ? :-D …

The panke.gallery is deeply interwoven with the panke-club which means that we suffer with them together as they can not open in this times… so we have to find new forms of support…

You can see [our editions] on our website. We used the appearance from a vinyl / record … because of our relation to the club culture … but inside there is only a link to a digital file … at the first edition it was like a signature handwritten by the artist … at the second it is an engraving …

DAM

Wolf Lieser founded DAM, the Digital Art Museum, in 1998, and in 2003 opened DAM Berlin as a commercial offshoot, where he sells work including digital files accompanied by a certificate, sometimes with signed documentation prints.

In a 2017 interview with Alessio Chierico for Digicult, he described his approach to selling digital work in relation to conceptual art and performance. While the materials are quite different, the psychology of collectors can be similar:

...I suggest that collectors should not regard their Digital Art acquisitions as purchased objects. Instead, they should see the money they spend on Software Art as a means of supporting the artist, and thus enabling him or her to continue to create artworks...

Software Art is now finding acceptance; there are a number of collectors who are willing to buy it, and the market for it is, as a matter of fact, actually growing. More than 50% of what I sell is either software or animation; both are sold on a USB-Stick or a CD.

if you stop to consider why people collect, or why they often become collectors: they are intrigued by the idea of owning something that is unique, (or of which only small numbers exist), and that you can experience at any given moment. It has always worked like that. Nobody collects iTunes files, because they are generally and easily accessible. On the art market, the demand for artworks with an edition of fifty copies is limited; it’s easier to sell a unique piece that costs ten thousand euro than fifty copies of something which only cost three hundred euros apiece. Works that come in editions of three hundred or five hundred are not very attractive; it is the aura of scarcity connected to an object that makes it attractive.

YOUar

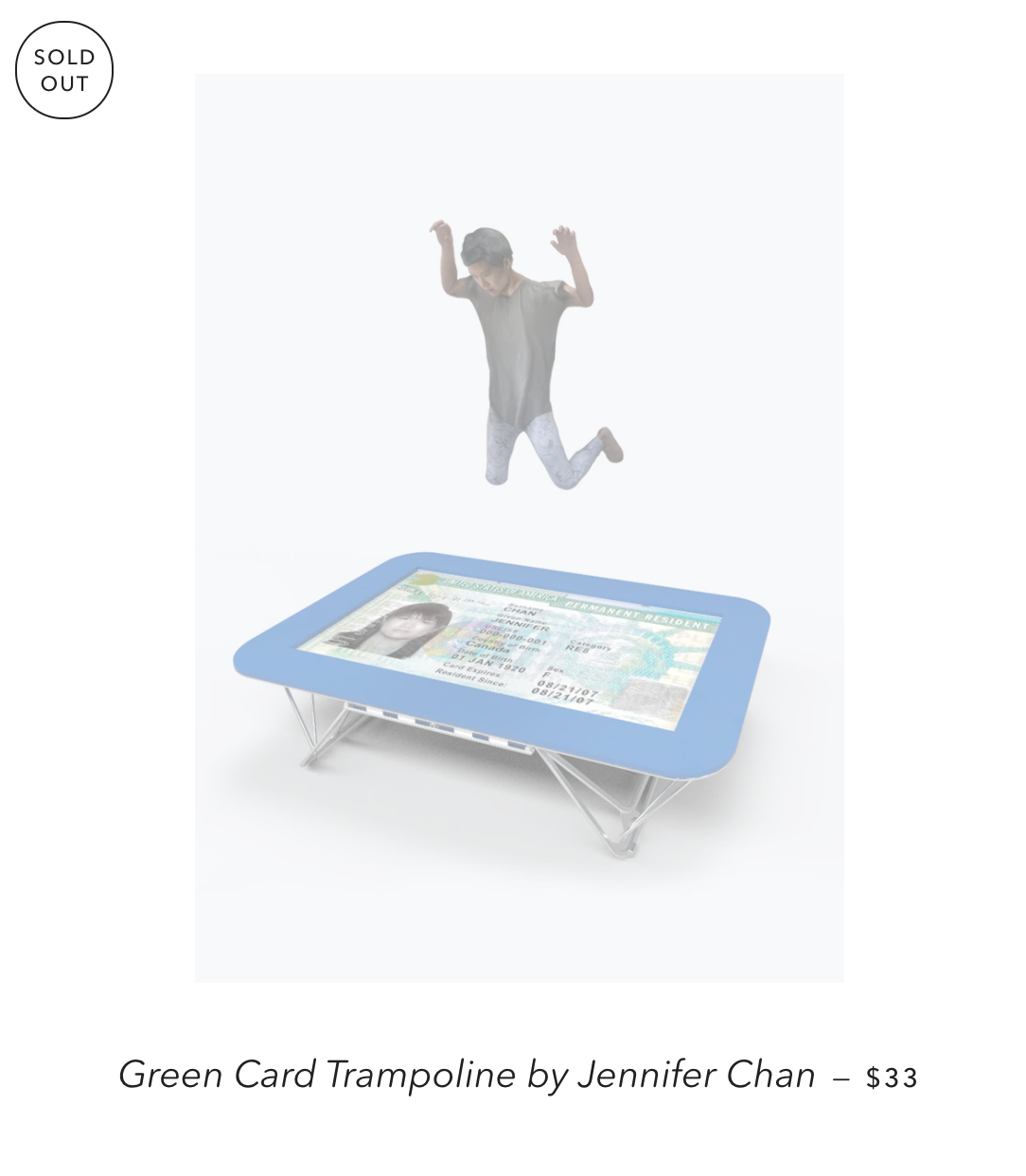

YOUar listing for Jennifer Chan, Green Card Trampoline (2020). Augmented reality object.

YOUar listing for Jennifer Chan, Green Card Trampoline (2020). Augmented reality object.

Founded by artist Jeremy Bailey, YOUar is “an ecommerce platform that sells Augmented Reality(AR) sculpture by artists directly to consumers. It eliminates the arduous limitations of traditional sculpture for both artists and collectors. Artists receive 100% of all sales on the platform and collectors receive a revolutionary product that would otherwise be inaccessible to many.”

The shop offers files both with and without physical packaging, though only the digital files sold initially. Works are also offered at a higher price tier that comes with a carpet with embedded QR code. In addition to their file, collectors received a locked and stamped PDF certificate of authenticity.

As ever, Bailey has a hot new idea for the future of the digital art market. “I am currently mulling NFTs but bothered by the financial cost but also to the environment to effectively offer a certificate of authenticity with little more security or even potential longevity than a PDF,” he writes. “Much of the hype seems to benefit those who have invested in crypto in ways that feel wrong for my practice. Instead, I’m considering more creative physical artifacts that can link to digital works via QR code. Specifically, right now I’m thinking mousepads. I believe the future is in mousepads. You can quote me on that.”

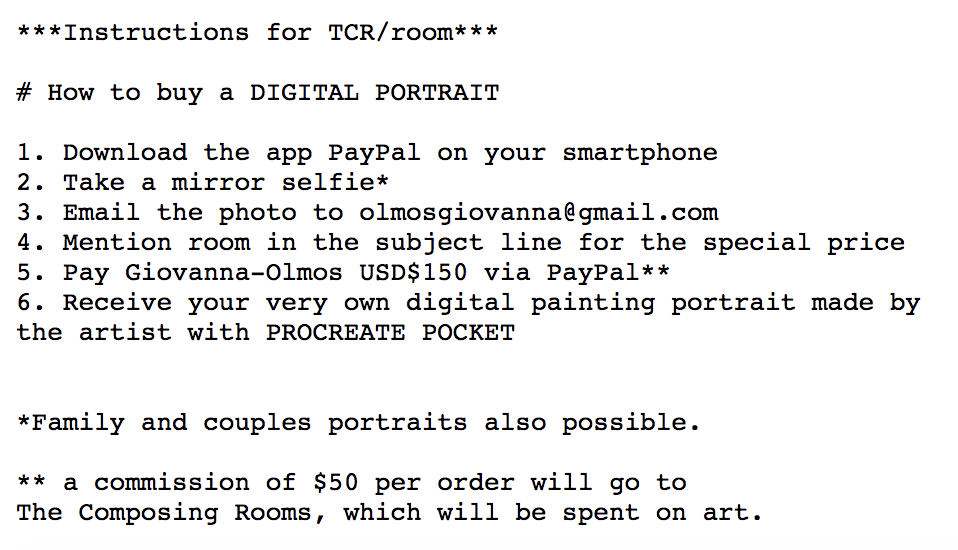

How to Sell a Digital Painting

Giovanna Olmos’ How to Sell a Digital Painting offered digital portraiture as a personalized service. In this project in which audience members were invited to send the artist selfies, which she would then paint on her iPhone using the smartphone app Procreate Pocket. She would then either “auction the work by asking the audience to bid, or selling it by prearranged price – rising from under $100 to $350 per commission due to popularity.”

Screenshot (detail) of instructions for How to Sell a Digital Painting, presented by room, 2016.

The work was presented by room, the online gallery curated by Cze Zara Blomfield alongside her project space The Composing Rooms.

There’s more...

After publishing this article, I received a deluge of messages with many examples that I overlooked. Apart from left.gallery, this article doesn’t get into the many other efforts to sell digital works via the blockchain prior to the recent NFT boom. Nor does it really cover the world of virtual collectibles, from the economies of online games like EverQuest to the StarbaseC3: The Starship Construction Site, the 1995 website where visitors could buy online space vehicles and parts. There's also a related history of the sale of virtual real estate, including notable examples like the Million Dollar Homepage, or even simply the example of domain squatting—buying up interesting-sounding URLs, and re-selling them for a profit.

For better or worse, efforts to sell digital artwork and virtual goods have been an important preoccupation at least throughout the history of the public internet, making the current NFT moment seem somehow both familiar, and unique.