In May 2014, artist Kevin McCoy sold a GIF onstage at Rhizome’s Seven on Seven conference to Anil Dash, and published the transfer of ownership of a GIF on the Namecoin blockchain. The data written to the blockchain included a link to the license, a link to the work, a hash (a kind of digital fingerprint) of the work, and a plain English assertion of ownership, as part of a system McCoy called Monegraph. Dash paid the entire contents of his wallet for this early experiment in selling unique digital works via the blockchain, which amounted to $4.

Fast forward to May 2018. Amid the sweltering euphoria of New York City’s early summer, an auction took place at the Knockdown Center, a sprawling warehouse in Maspeth, Queens, as part of a cryptocurrency conference. Fueled by amicable competition among notable investors in the room, bidding reached $140,000 for an artwork by Guile Gaspar that featured a kind of digital collectible called a CryptoKitty. A hardware wallet embedded in the physical work secured a digital token that allowed the CryptoKitty to be traded, sold, and (ugh) “bred” as a digital good in the CryptoKitties marketplace.

It was a memorable moment in the rise of NFTs, or non-fungible (that is, unique and non-interchangeable) digital tokens that are registered on the blockchain. Even though the work had a physical dimension, it was hard not to interpret the auction result as a major show of confidence in the idea of trading unique digital goods via cryptocurrency, in the standard that made it possible, and in the game that popularized it. It also seemed to illustrate something McCoy and Dash had observed in their first presentation: cryptocurrency had been in need of something meaningful to do, and for now, this was it.

Three years later, following improvements to the efficiency of the Ethereum network and a boom in the value of many cryptocurrencies, the sale of digital collectibles via NFT is everywhere. Christie’s auction house made headlines for the auction of a large-scale work by an artist named Beeple, the artist Christopher Torres sold a remastered Nyan Cat gif on Foundation for a large sum, and a number of artists in Rhizome’s community have sold work at varying levels via this new market, even while the prevailing aesthetic is more closely aligned with a platform like DeviantArt. This has to be acknowledged as a success for the NFT art market; as pointed out on a recent episode of the New Models podcast, it is, for now, turning abstract wealth that’s locked away in secure locations into actual money that people can use to feed themselves and their families and pay rent, and that can sustain experimental platforms like Felt Zine.

The NFT boom has been a kind of revelation. It should always be the case that artists can keep the wolves from the door and have their creative labors validated, even when the result is a digital file, but the market has never really supported this; the idea that it’s even possible feels revolutionary.

At the same time, the NFT backlash has been furious. Highly visible NFT evangelists make unrealistic claims to be freeing artists from the problems of institutional gatekeepers, but there are clearly still problematic dynamics of race, class, power, and gender that shape these markets too, and artists still find themselves partly reliant on social media platforms and traditional institutions to build audiences and accrue value for their work. Arguments and Clubhouse rooms that have now started could last forever because, like so many other aspects of cryptocurrency culture, they seem to boil down to questions of faith. As Ben Vickers points out, “it’s not since the early formation of the Christian Church that a text or doctrine handed down without claim to authority has produced such extreme sectarian conflict and zealotry” as the original Bitcoin white paper.

Given the faith-based arguments being made for both cryptocurrencies and art markets, it’s helpful to try to take a more material approach. In my own efforts to do this, I’ve found it instructive–following a cue from Tim Whidden and New Models–to look back to CryptoKitties.

CryptoKitties is a trading and “breeding” game that was heralded by some as “the killer app” for the Ethereum blockchain. The game became so popular that CryptoKitty transactions congested the Ethereum network, ultimately seeming to pose a nearly existential threat. Its popularity was likely due in part to the fact that it was kind of difficult to use Ethereum currency for very much at that point in time, and that the game could result in a profit for the shrewd player. Also, as we know, the internet is for cats.

But beyond that, the success of the CryptoKitties team rested in large part on their introduction of the ERC-721 standard, which defines the minimum elements of a smart contract—code that is executed on the blockchain when certain conditions are met—for a unique digital collectible on the blockchain, and it’s still the basis for Ethereum NFTs. It was quite well-designed for the purposes of a cat-based trading game, but is perhaps less perfect for born-digital art at large.

Ownership and Property

The first generation of CryptoKitties were all created by developers, and so their authenticity was guaranteed by the app itself. In addition, the smart contract governing the app hard-coded a preset limit to the number of Kitties that the developers could release, which meant that users could trust that the market would not be flooded. This kind of guarantee of limited supply and authentic provenance does not apply to today’s NFT art market; stories abound of artists like Rosa Menkman discovering that their work has been minted and sold without their consent, sometimes under their own name.

Another important distinction between CryptoKitties and born-digital art is that the former had a kind of use function. In the er, White Papurr, its makers pointed out that interest in previous digital marketplaces had waned quickly because one couldn’t do anything with their collectibles. So CryptoKitties had a “breeding” feature, and players would pay one another for particularly attractive arrangements. In traditional art collecting, collectors also feel this urge to do something with their works, to hang them and rehang them, loan them to museum exhibitions, or flip them. In the case of NFT art, there’s less that one can obviously do with one’s bounty besides participating in secondary markets.

The model of art ownership implied by NFTs has been a matter of some debate, and here, too, a comparison is instructive. Crucially, all of the imagery associated with all generations of CryptoKitties remained under the copyright of the developers. This definition of ownership was not specified in the ERC-721 standard itself; it’s found in a separate license that governed the use of the app: “you own the underlying NFT completely. This means that you have the right to trade your NFT, sell it, or give it away.” But, “your purchase of a CryptoKitty, whether via the App or otherwise, does not give you any rights or licenses in or to the Dapper Materials (including, without limitation, our copyright in and to the associated Art) other than those expressly contained in these Terms.”

It’s a generous license that allows users to have a broad range of rights to use their Kitties publicly, but given the recent debates about what it means to own an NFT artwork, this is a really important precedent: in the view of the makers of CryptoKitties, the NFT itself did not offer a general definition of what it meant to “own” a work, or what rights rested with creators.

The implication of all of this is what it means to own an artwork governed by an NFT is not some settled fact. Ownership needs be defined alongside the sale of an NFT, via a standard contract, or another kind of smart contract (Zora is one example of a marketplace that is doing interesting work in this area). I’d argue that even just an email or handshake agreement would help, because most art sale contracts are only ever used to clarify expectations and prevent misunderstandings, even if they aren’t bulletproof legal documents. This is actually an area where ERC-721 took a step backward from McCoy and Dash’s concept—in the standard demonstrated in that 2014 transaction, there was space for a (linked) legal and (embedded) plain English definition of ownership.

Interestingly, the license developed by CryptoKitties also considers “any art, design, and drawings that may be associated with a CryptoKitty that you Own” to be covered by the terms of the token sale. This recognizes a further limitation of the NFT, which is that it typically encodes a particular file, such as a PNG. This idea of the artwork as a given file, preserved in amber forever, runs counter to prevailing ideas of born-digital practice, in which variability is seen as a defining feature. As artist Sterling Crispin has pointed out, a standard NFT purchase is often more like buying a print or poster, a fixed point in the dynamic system of an artwork. This way of working is well suited to an artist like Travess Smalley, whose work is currently on sale on the Folia platform, but perhaps less so to artists who prefer to exhibit dynamic software-based work.

Currently, the use of NFTs to regulate intellectual property seems kind flawed and boring—a means to a very important end, in that it allows artists to tap into a new form of financial support, but with plenty of long-term problems one can anticipate. At Rhizome, we’ve found that immutability is not necessarily beneficial to the long-term stewardship of digital art. Histories need to be rewritten, artists change genders and names, authorship conflicts emerge years after a work is originally published. On the technical level, there is also a need for dynamic approaches to stewardship: resources external to the artwork get lost or deprecated and need to be reconstructed, and artworks need to be moved in between ever-changing, in many cases highly proprietary software environments that even might or might not support certain encryption algorithms. We’ve also found that blockchain-based preservation projects can themselves require external support in order to maintain ongoing access to the interfaces to their records and contracts.

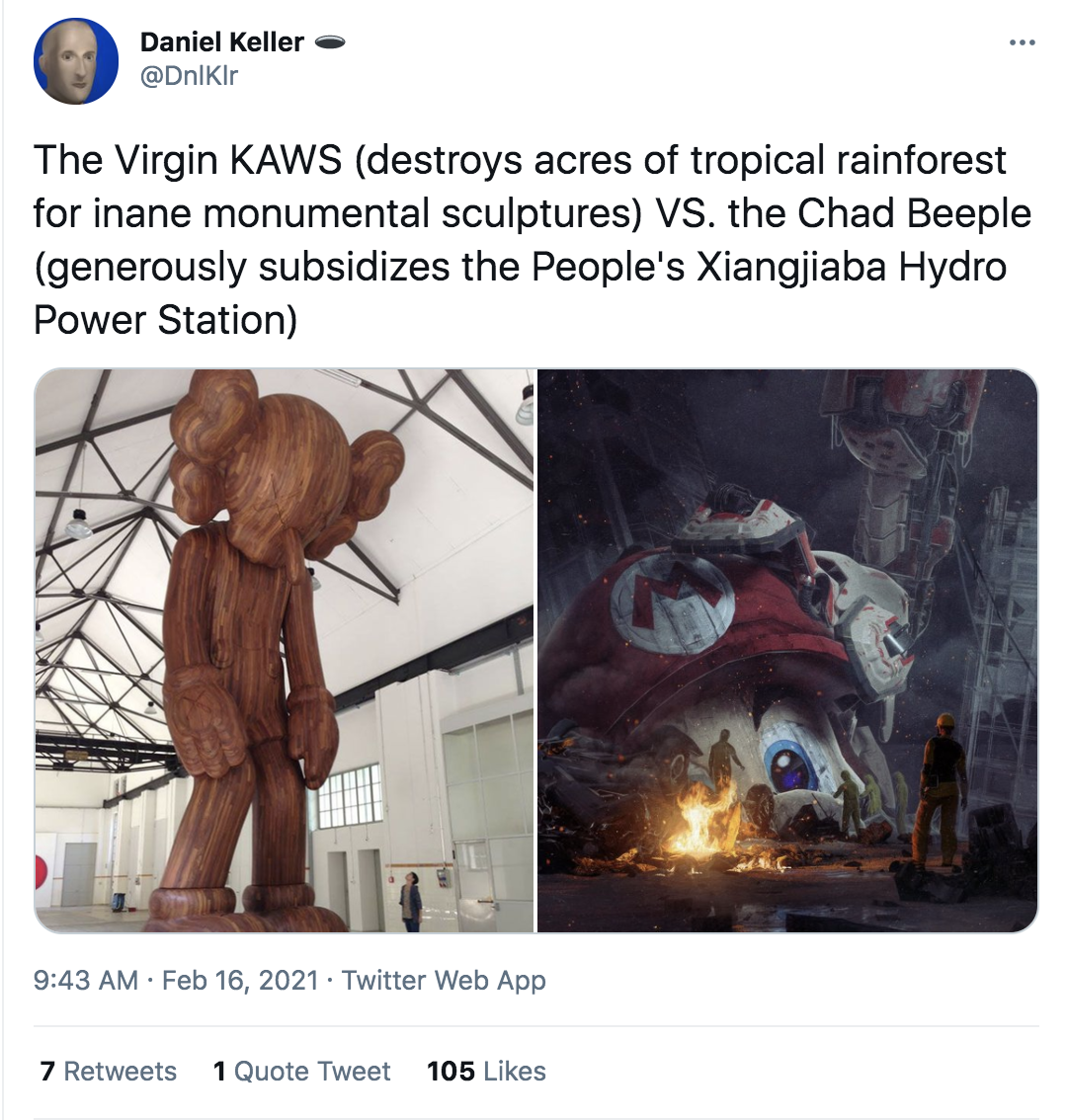

But NFTs could become a lot more interesting when, instead of forcing digital art into PNG form, they begin to operate as networked software tools that can facilitate new kinds of collaboration—forms of experimentation that, as Daniel Keller has pointed out, tend not to happen when market frenzies lead to high transaction fees and place all the emphasis on speculation. For the moment, we’re stuck in that moment when, after an artist gives a lecture bout their life’s work, there’s time for one more question, and someone in the audience asks about how they deal with copyright.

Infrastructure and Climate

Beyond intellectual property, the infrastructure required to support NFT minting has been a particularly controversial topic. With CryptoKitties, we saw how playful trading of digital art had serious material implications for the network as a whole. Transactions on the Ethereum network are verified by a system called proof of work, which involves forcing computers to solve meaningless, difficult equations before data can be written to the blockchain. This raises the cost of writing fraudulent data to this shared record, allowing for financially high stakes transactions to be recorded without a central authority like a bank. It’s hardware intensive and energy intensive, and massive arrays of dedicated computers around the world, often stationed close to low-cost power sources, crunch these numbers to receive small financial incentives in a process called mining.

The CryptoKitties debacle helped spark major improvements on the Ethereum blockchain, but the most important change has not yet happened: the shift to an alternate system of authentication called proof of stake, which is vastly less resource intensive. In this system, users put currency at stake in order to verify transactions, rather than putting computer hardware and energy at stake, and they receive an incentive when consensus is reached. This transition is promised for later this year, but from an outsider perspective, the challenge of implementing this radical change on a busy, high-value network seems incredibly daunting.

While minting NFTs on the blockchain is quite resource intensive, it may not be quite as bad for the environment as it first seems. First, as a recent post from NFT marketplace SuperRare pointed out, it’s not the minting itself that creates work for the Ethereum network; minting does not increase the network’s energy consumption, but it does underwrite the mining costs of the network as a whole, particularly when the network charges exorbitant fees to mint a work. Beyond that, while exact figures do not exist, a significant portion of the world’s mining is powered by renewable sources, heavily centered in China’s Sichuan province, where excess hydroelectric capacity is harnessed by mining facilities. For now, the economics of cryptocurrency mining just don’t really add up without abundant hydroelectric or geothermal power. It’d be more worrying if falling fossil fuel prices and rising crypto prices changed this.

Yuri Pattison, the ideal, 2015. Artist’s video depicting a cryptocurrency mining operation in China, located near a hydroelectric power plant.

Still, given the vast use of resources, it could be politically effective (if not economically viable for everyone) for artists to refuse to mint NFTs on Ethereum until it makes the promised shift to proof of stake mining. There is a growing movement for green NFTs, and an Eco-NFTs Discord, which aim to advocate for these issues. For their part, the makers of CryptoKitties haven’t waited around for Ethereum’s promised improvements–they built their own proof-of-stake blockchain, Flow, which powers their new collectibles juggernaut, NBA TopShot, and other platforms, including the art marketplace VIV3.

We Have to Change Our Money

If the NFT-backed art market is just a kind of art version of sports memorabilia, though, it’s also something kind of profound, an opportunity to think through what a different and more equitable art market would be like. For example, while she has not minted an NFT yet due to environmental questions, Sara Ludy has used the NFT as an opportunity to develop a new contract with her gallery that is more supportive of the gallery’s staff. Likewise, much has been made of the potential for smart contracts to offer automated resale rights for artists to benefit from secondary market sales, although bad faith actors can find ways around these just as they can in the traditional art world. Cryptocurrency is not a prerequisite for these ways of working, but in some way, it does open up a conceptual space that seems to prompt this type of thinking. This is the space created and explored by Nora Khan and Nick James Scavo with this 2015 piece for Rhizome, by Furtherfield with Artists Re:Thinking the Blockchain and DAOWO, and by Mat Dryhurst and Holly Herndon with through their ongoing Interdependence podcast. Cryptocurrency does offer some opportunity to define terms anew, even if the terms just end up in a traditional license alongside the NFT. It’s like this amazing video by Babak Radboy, where he argues that “if we want to change the world, we have to change our money.”

The idea of a new kind of money and a new kind of art market are powerful and important, but dangerous if taken too far. Both NFTs and the traditional art market have a significant carbon footprint. Both involve negotiable ideas about what constitute the artwork, and what constitutes ownership of it. Both involve the staking of monetary value based on reputation, perceived desirability, a good sales pitch, and more. Dynamics shaping the NFT art market are rooted in material infrastructures, politics of nation states, deep-seated societal power relations, barriers of language and access. To achieve the kind of change Radboy describes, we need to treat the NFT not as an entirely new instrument, but as one that’s embedded in these existing social realities.