ZZYW (Yang Wang & Zhenzhen Qi) is a New York-based art and research duo who examines the cultural, political, and educational imprints of computation. Their work ThingThingThing (2019), included in the ongoing exhibition “World on a Wire” at Hyundai Motorstudio Beijing and online at worldonawire.net, is a computational system made for collaborative worlding, resulting in a live simulation in which entities generated by users interact in an ever-evolving three-dimensional world. The below essay explores the history and thinking behind ThingThingThing. You can see the work itself here.

The duo will host a collaborative worlding workshop online on February 25th at 7pm. No prior experience is required to participate, though the event is limited capacity. Learn more about the event and RSVP here.

“User Friendly”

Today, life seems increasingly prescribed, recursive, normalizing. Stories depicted by mainstream media are increasingly divided. What are the conditions that enabled such narrowing experiences?

Pervasive computing is a term first created by Mark Weiss, the then CTO of Xerox PARC (Palo Alto Research Center) in 1988. Commenting on cumbersome mega computers that were difficult for everyday use at the time, Mark described the original intention of pervasive computing as “A less-traveled path I call the ‘invisible’: its highest ideal is to make a computer so imbedded, so fitting, so natural, that we use it without even thinking about it.” Mark Weiser’s new vision was widely influential in Silicon Valley. Software processes such as machine learning and AI are integrated into analog objects, making them automated, assistive, and “smart.” A smartwatch can vibrate and discretely remind us to end meetings on time. A smart mug can keep our coffee warm.

However, pervasive computing paints a very different picture when applied to cultural production — a territory previously rarely traversed by algorithms. According to AI Now Institute at New York University, an increasing amount of employers are integrating pervasive computing as part of their HR hiring process. Through AI algorithms, employers can extract social media patterns from potential employees and compare them to their social media content. Then, the algorithm calculates a probability of likeness. Trained from past behavioral data, this process naturally mirrors the historical trends of employment. Women, minorities, and other historically underrepresented populations will continue to be portrayed as less fitting. Software predicts the future based on fixed patterns from the past. As a procedural language designed to administrate systems, it produces solutions instead of experiences, narrowing focuses instead of broadening perspectives.

What Does A System Want?

A system is not static. It is a dynamic entity made up of interrelated, interdependent parts, members, or agents. The word system first appeared in publications in 1948. Ludwig von Bertalanffy used the term to describe various organismic scientific phenomenons he had observed as a biologist.

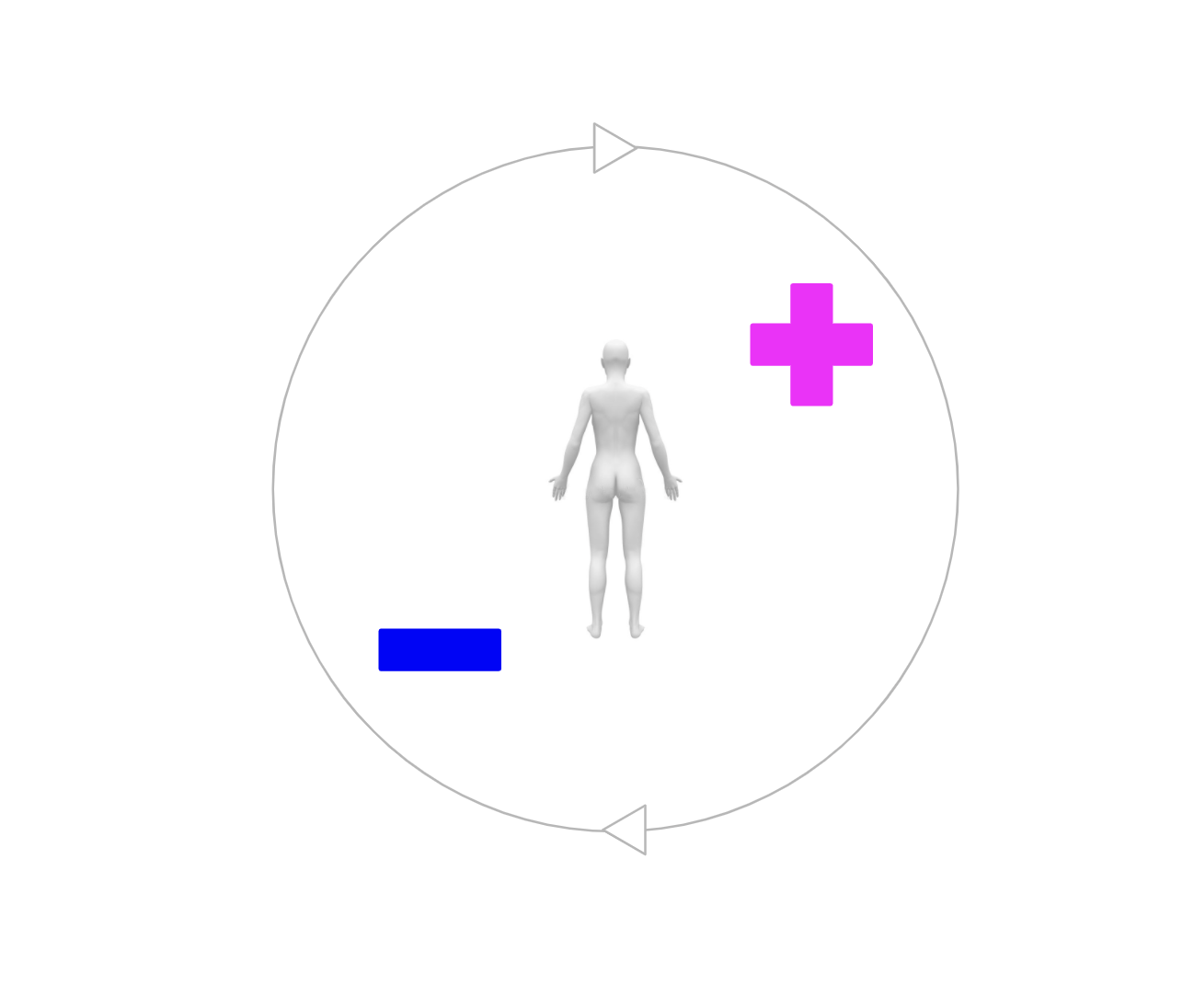

Human Body Regulates Temperature Automatically with Control Actions. Source: zzyw.org

Human Body Regulates Temperature Automatically with Control Actions. Source: zzyw.org

The human body is one of the most ubiquitous biological systems we encounter daily. When we feel cold, our muscles shiver to generate heat and warm up our body. When we are hot, we sweat and evaporate heat from our bodies. Without us paying conscious attention, our body automatically maintains a standard temperature range to keep us comfortable and healthy. Since this type of system always takes actions to cancel out excessive effects and bring the current state back to its norm, we refer to the canceling process as negative feedback. Systems involving negative feedback tend to resist change and maintain a stable internal environment. System theory refers to this tendency as homeostasis, and the stabilizing state the equilibrium state.

Besides natural science, negative feedback is also widely adopted in engineering processes and machines. For example, there is a cruise system built into cars. It uses control actions to ensure a stable driving speed without any delay or overshoot. Cybernetics is the science of exploring regulatory, purposive, and normalizing systems. Today, the advance of cybernetics research allows us to enjoy precision and predictability with a level of efficiency we never imagined before. Self-driving cars automatically steer directions to avoid obstacles and optimize routes. Social media algorithms recommend new YouTube videos, shopping lists, and even new friends based on our past behaviors. Digital writing software suggests words we are more likely to type together. In the past, we had difficulty making sense of the world. Today, we live in a world that’s filled with buttons, solutions, and answers, feeling more trapped than ever. A Cybernetic system tends to neutralize towards a specific direction, and therefore it is not neutral to most of its constituents.

Can A System Open Up?

Systems do not always narrow down. Sometimes, when its members interact with each other, it could result in entirely new properties that could not be anticipated from its individuals’ characteristics alone. For example, computer scientists can simulate an infinite amount of flocking patterns from three simple rules, Separation, Cohesion, and Alignment.

Emergent behavior simulated by computational algorithm. Source: ayearincode.tumblr.com

Emergent behavior simulated by computational algorithm. Source: ayearincode.tumblr.com

When patterns appear from within the system without centralized planning, we call it Emergence. Besides biological and mechanical systems, emergence can also happen in a social system. According to American sociologist Neil J. Smelser, if a group of people can communicate with each other, face the same constraints, believe in similar actions, have individual agency, they will inevitably act together to create differences.

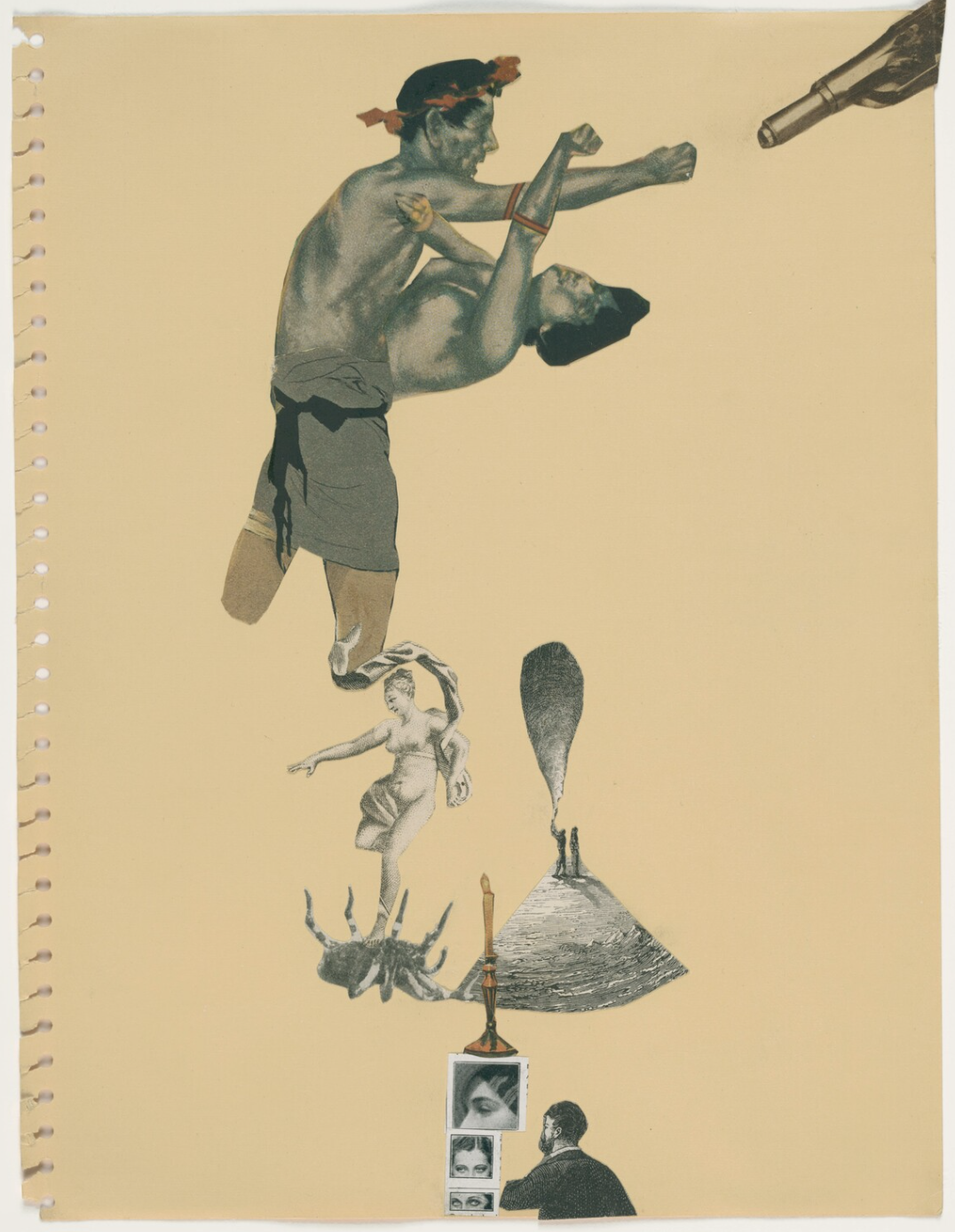

Historically, artists from different artistic moments have adopted collaborative making to redefine the boundary of creative expression. For example, Cadavre Exquis (exquisite corpse) is a collaborative drawing approach first invented by surrealist artists Yves Tanguy, Jacques Prévert, André Breton, and Marcel Duchamp in the 1920s. Bounded by the limitation of a single person’s imagination, they jointly created a new game or system of drawing. Each previous drawer folds up the sheet of paper, revealing only a small portion at the end before passing it on to the next drawer for further contribution.

Because of the unique perspective introduced by each collaborator, systematic collaborative drawing generates bizarrely imaginative compositions beyond outcomes planned by a single individual. When transitioning between drawers, hiding contents temporarily disables causes and effects, allowing each contributor to escape beyond one’s thinking mind. Meanwhile, the small portion of content revealed to subsequent drawers loosely binds independently contributed visual elements into a coherent meta-narrative.

Cadavre Exquis with Esteban Francés, Remedios Varo, Oscar Domínguez, Marcel Jean. Untitled. 1935. Source: moma.org

Today, collaborative making processes are increasingly facilitated by technological platforms. Inspired by Cadavre Exquis, we conducted a small experiment online. The goal is to reproduce a famous quote by Yoda, a fictional character from the Star Wars movies, among 160 members belonging to the same private social media group. The original passage reads, “Fear leads to anger. Anger leads to hate. Hate leads to suffering.” The instruction I posted in the social media group is: Each new writer would contribute a sentence with the structure “____leads to ____.” The first blank is the last word from the previous writer. The second blank is a new word contributed by the new writer. This experiment extended for three days, transforming the original Yoda quote into a wildly expanded version:

“Fear leads to Anger. Anger leads to Sandwich. Sandwich leads to Truth. Truth leads to Boredom. Boredom leads to Impotence. Impotence leads to Wealth. Wealth leads to Separation. Separation leads to reproduction. Reproduction leads to Hotpot. Hotpot leads to Diarrhea. Diarrhea leads to Petting Cats. Petting Cats leads to Moving In. Moving In leads to Earth Quake. Earth Quake leads to Economic Crisis. Economic Crisis leads to Withdrawing from School. Withdrawing from School leads to Soda. Soda leads to Urbanization. Urbanization leads to Low Morality. Low Morality leads to Stock Market Shorting. Stock Market Shorting leads to Inflation. Inflation leads to Stupidity, and Stupidity leads to World Peace…”

Compared to the drawings from the 1930s, this collective anadiplosis experiment produced an emergent narrative with different characteristics. The 1930s experiment revolved around topics such as religion and industrialization. In light of COVID and the global political unrest, the more recent experiment reflected a sense of collective unsettlement. Because the online environment is asynchronous and partially anonymous, it invited more loosely connected individuals to contribute within a more extended period. Group members who were reserved for posting comments also participated in the collective writing format.

Systems have a tendency to perpetuate their normalized state, and collective actions from within can sometimes generate emergent forces to counter this tendency and force the system to open up. Every time we dance, we are countering our body’s tendency to remain on the floor. Every time we work on a file on the computer, we counter its tendency to perpetuate a mechanical way of organizing data. Social scientists have attempted to theorize this transcending motivation. Two of such theories are Contagion and Convergence.

Contagion

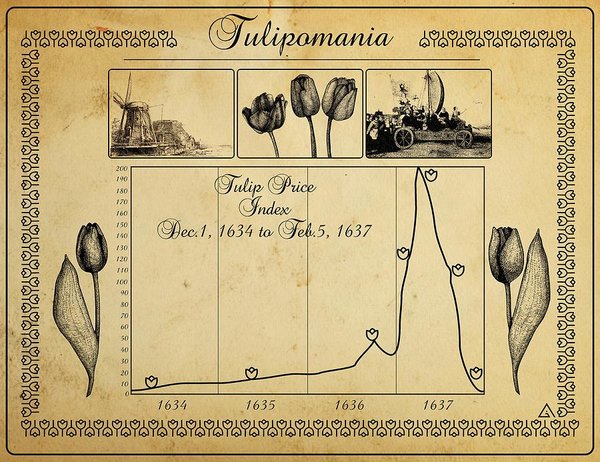

In sociology, Contagion refers to a special form of Emergence whereby individual members seems to have temporarily surrendered individual consciousness, and repeat the crowd action unconditionally. Similar to how viruses automatically spread when their hosts come into contact, human beings have a natural tendency to mimic each other’s actions. A classic Contagion phenomenon happened during the Dutch Gloden Age when prices for tulip flower skyrocketed and plummeted within a single month in February 1637.

Tulip trading price between 1634 to 1637. Source: ecotalker.wordpress.com

Tulip trading price between 1634 to 1637. Source: ecotalker.wordpress.com

At the peak of the bubble, the price of a single viceroy tulip reached five times the worth of an average house at the time. The Contagion Theory was originally developed by Gustave Le Bon. Dutch psychologist Jaap van Ginneken compared Le Bon's theory to “Hypnotized individual finds himself in the hands of the hypnotizer” (Ginnkeken, 1992). Le Bon’s theory is widely criticized by twenty-first-century crowd psychologists such as Stephen Reicher. Reicher claims that members did not lose their agency, but rather were motivated by distant causes that did not seem to be immediately connected to the collective action itself.

Convergence

Another theory is that like-minded members of a group can draw from each other’s presence. Originally developed by Floyd Allport in 1924, the Convergence theory was expanded upon by Neil Miller and John Dollard in 1941. When seeing others acting in similar ways, individuals can feel that the responsibility of the actions is shared by multiple actors, instead of him or herself alone. This can generate a sense of security, revealing hidden tendencies of individual members who haven’t previously acted in a certain way, and intensify a sentiment shared among group members.

A World Is Not A System

Collective actions among human members do not take place in well-defined systems. They happen in a world. A world shares many similarities with a system. Similar to a system, a world has boundaries that separate it from the outside environment. A world takes actions and maintains its balance. A world is not static but in a constant state of flux. Once in a while, a world emerges from the pain of growth, transcending into a new realm. However, artist Ian Cheng thinks that a world should also contain mystical figures (Cheng, 2019): “A World manifests itself in its members, emissaries, symbols, tangible artifacts, and media, yet it is always something more.”

Ian Cheng, Emissary in the Squat of Gods (live simulation and story, infinite duration, 2015). Source: theartnewspaper.com

Ian Cheng, Emissary in the Squat of Gods (live simulation and story, infinite duration, 2015). Source: theartnewspaper.com

Systems are abstracted versions of the world. The world is a system rendered with uncertainties, vulnerabilities, trauma, and catastrophe. A world is a piece of music, a series of oscillations between stable octaves. A world is both harmony and chaos, woven together through serendipitous encounters of mythical creatures living inside. A world is both a tool and an effect. A world is a hazy zone of ambiguity — always there but never completely revealed. A world grants its occupants permission to do things that might be inexplicable. A world is sometimes slow and useless, defying all explanations. A world tends to be stagnant. Its inhabitants possess the secret power to activate it in times of need.

Collaborative Worlding

Worlding is the active making of a world. Worlding is holding “the Open of the world” (Heidegger, 1971). In ancient times, worlds were made with blades and scrapers. In modern times, worlds were made with machines. The world we live in today is constructed through pixels, soundbites, data, and algorithms. We interact with the world and each other through computers, a set of containers for rules and relations. To be in an active relationship with the world we now live in, we must “erase the world, subjecting it to various forms of manipulations, preemption, modeling, and synthetic transformation” (Galloway, 2012). Instead of observing it losing color, we must restore its magic through a set of actions.

Art Museum Visitors As Worlders

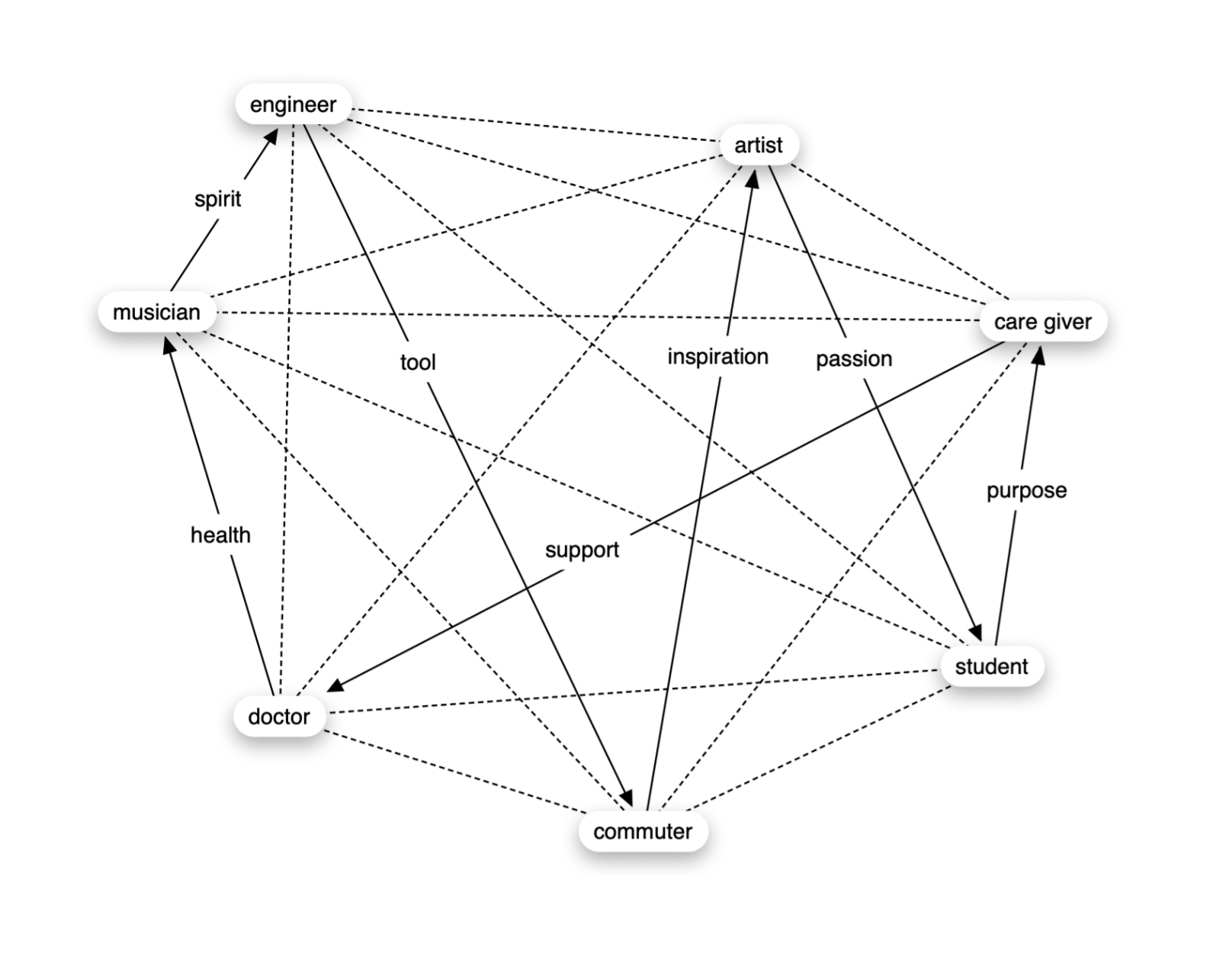

Creating a world sounds like a daunting task. All of us have lived in a world, but very few can say we created one. What kind of virtual world could be created among a group of engineers, artists, students, caregivers, commuters, teachers, musicians, chefs, nurses, moms, and more? As an experiment, we asked art museum visitors worldwide: If you have the power to create a world, what would it be like? As it turns out, every visitor already has ideas about worlding. We were told that a virtual world should “have a giant pig that says 'hi' in Chinese, and a tiny cloud that says 'goodbye' in German, warriors that can hide or defy gravity, and cactuses that lay eggs in the shape of rainbow-colored cubes.” We were also told that a world “should be viewed from many different perspectives, and every creature should be seen…” We learned that anyone could be a worlder, the moment when they are asked to become one.

A Conceptual Model of Collaborative Worlding. Source: zzyw.org

A Conceptual Model of Collaborative Worlding. Source: zzyw.org

The World of ThingThingThing

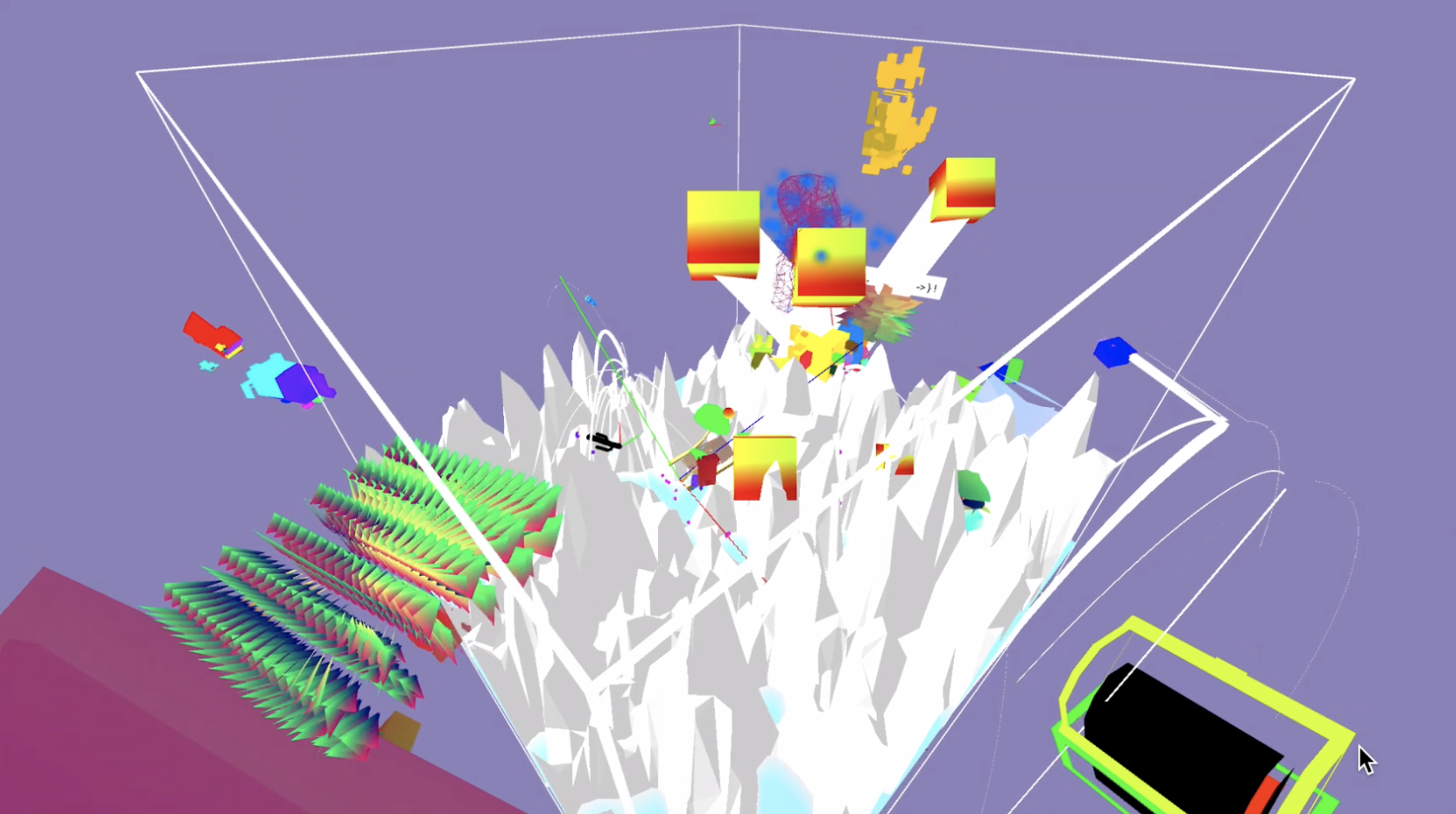

ThingThingThing, a virtual simulation made collaboratively. Source: zzyw.org

Over the past two years, with visitors from seven arts and cultural institutions worldwide, we have made ThingThingThing. ThingThingThing is a computational system that invites museum audiences to take part in collective worlding. It is built with easily-accessible tools and interfaces, allowing everyone to contribute a computational object of their own. All computational objects created by audiences are integrated automatically by the software algorithms. The result is an ever-evolving, never concluding, the three-dimensional system of instantiations, created by everyone yet owned by no one.

ThingThingThing is a world that inspires questions rather than answers. Where does it begin or end? Where are its center and edge? What are its goals? How should its members encounter each other? Does it optimize towards any goals? What motivates such optimization? What does it mean to inhabit a world where rules are constantly rewritten, and no one is in control?

References

Galloway, A. R. (2012). The interface effect. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

Cheng, I.(2019, March 5th). Worlding Raga: 2 — What is a World? ribbonfarm. https://www.ribbonfarm.com/2019/03/05/worlding-raga-2-what-is-a-world/

Thompson, E.(2007). The tulipmania: Fact or artifact? Public Choice, 130 (1–2), 99–114, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-006-9074-4

Heidegger, Martin. Basic Writings, "On the Origin of the Work of Art.” 1st Harper Perennial Modern Thought Edition., ed. David Farrell Krell (New York: HarperCollins, 2008, pg. 143-212).

Heidegger, M. (2008). On The Origin of the Work of Art. Duke University. https://people.duke.edu/~dainotto/Texts/heidegger.pdf