Katherine Frazer, ~* ☘️☘️☘️trraforming33333 🌀endlss bliss 🥴 . . .?, 2021. PNG export from a Keynote presentation file. Courtesy of the artist.

The latest in a series of interviews with artists who have a significant body of work that makes use of or responds to network culture and digital technologies.

Celine Katzman: Flowers are a recurring theme in your digital painting practice, including in your dynamic desktop wallpapers, Keynote paintings, and your online exhibition at External Pages, ∞ bouquet ∞ toss ∞ feeling, it’s just for you (June 7 – August 22, 2021). You’ve been studying at the Sogetsu school of Ikebana since 2017 and maintain a physical flower arranging practice. How has studying and practicing Sogetsu-style ikebana informed your digital painting practice? Have you shown your paintings to your ikebana teacher?

Katherine Frazer: I started studying Sogetsu Ikebana after having a dry spell with making visual art. I was working long hours at my day job, and felt burnt out. I was disappointed in how little work I was producing, so I sought out a new hobby that would provide accountability and structure for me to be creative.

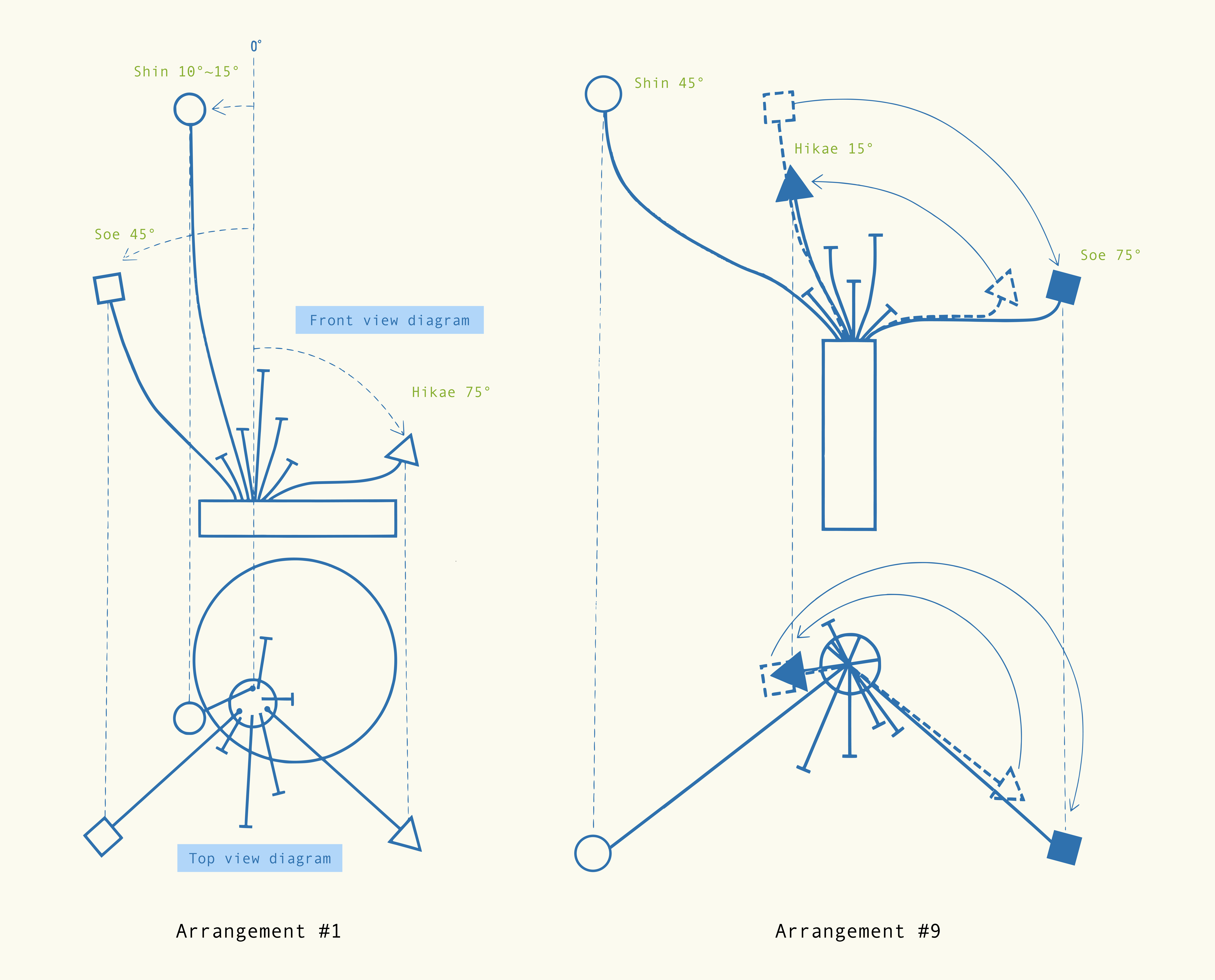

Diagrams from the artist adapted from Sogetsu Textbook 1, Hiroshi Teshigahara.

Diagrams from the artist adapted from Sogetsu Textbook 1, Hiroshi Teshigahara.

Beginner ikebana lessons are prescriptive. The first forty lessons require you to create flower arrangements that follow diagrams in a textbook that are all derivative of the very first flower arrangement you make. You use the same number of flowers, the same proportions, with only minor tweaks in the angles you bend the flower stems at. Only after you complete the first two textbooks, can you move onto more freeform expression.

Even though the first forty arrangements are all built from the same building blocks, the personalities of these arrangements differ greatly. I have tried to emulate this methodical, iterative and simplistic approach in my art practice.

In ikebana, you work with the flowers. You are supposed to emphasize the natural beauty within them. There’s a saying that “beautiful flowers don’t always make beautiful ikebana.” Similarly, when I create a painting, I try to emphasize the particular quality of a line, color, or texture. It may not be the most striking element of an asset, but in combination with other assets, it creates a harmonious composition. Like pruning leaves on a flower to draw attention to the curvature of the stem, I extract and remove excess material from 3D models and photographs to emphasize the essence of the formal qualities I find most attractive.

I’ve shown my ikebana teacher my paintings. She enjoyed them, but immediately emphasized that they are not ikebana! She said they are more like European style bouquet design, which is true.

Katherine Frazer, Painlets iv, 2021. Digital painting created in Figma, 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

Katherine Frazer, Painlets iv, 2021. Digital painting created in Figma, 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

CK: You’ve previously worked as a designer at Apple on the Keynote team and as a designer at Figma, and you use both tools to make digital paintings. How does your work as a designer of these tools influence your use of them as an artist and vice versa? What are your favorite ways to (mis)use each software?

KF: It’s a way for me to have fun, and think of the software I’m intimately familiar with in a new light. I used to make countless presentations in Keynote for work. I really lived in the app—before other user interface design tools like Sketch and Figma took off, I used to draw mockups of Keynote, Pages and Numbers in Keynote!

I was previously designing the constraints and limitations of these apps. Now, I am looking for ways to surprise myself, and use them to unintended ends. While they’re built for professional use, it’s heartening to think there are opportunities for play even in the most mundane of places. Tools are what you make of them.

Similar to working with the natural elements of flowers in ikebana, I’ve found that particular software has certain personality traits. It’s important to work with the natural strengths of each app, and emphasize those characteristics. Keynote is great for working extremely fast and iteratively. It’s easy to remove backgrounds and work with photographic imagery. Figma is less fast paced, but it’s easier to achieve sublimely digital vector compositions. Figma also allows for much larger file sizes, and collaboration with peers.

Aside from my personal connection to these apps, I like that they’re available for free on the web. People have sent me their own Keynote paintings, and joined me real time in Figma files to create compositions. I like this participatory element to the work, and I hope it demystifies how digital artifacts are made.

CK: You minted ikebananana2 – sketchbook as an NFT on the Foundation platform during the NFT Aesthetics panel on May 4, 2021, and Rhizome accessioned the work to ArtBase. The work is an Apple Keynote presentation file which you describe as an interactive sketchbook containing 53 sketches (one per slide), where each slide contains an altered version of the previous one, offering a unique window into your painting process. Given how iterative your process is, how do you decide which sketches are finished paintings? Do you return to unfinished paintings later or archive them?

Katherine Frazer, ikebananana2 – sketchbook (Timelapse), 2021. Timelapse presentation, 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

Katherine Frazer, ikebananana2 – sketchbook (Timelapse), 2021. Timelapse presentation, 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

KF: I try to work in a way where anything I create contributes to other things I will create in the future. I refuse to use the delete key, and always opt to duplicate an asset, slide, or file immediately. My Keynote files usually have between 50 and 100 slides with different compositions in them. I try to limit one “idea” to each file though.

No one particular slide takes a long time to create. Gradually over the span of a presentation however, the slides usually get more and more complex. I don’t spend more time on later slides, but this process creates repositories that have a snowball effect. I am able to copy and paste pieces of older compositions together to create more layered, intricate new ones. I am extremely incremental.

I rarely have a concrete idea of what I want to produce, and often look back on old files to see if anything strikes me, and use that as a jumping off point. I’ve tried to set up processes in place to make creating work as easy as possible for myself. Keeping archives around means I never start from scratch.

When a painting is “finished” is an intuitive process. Painting is a bit like playing chess with myself—I’m done with a painting when I’m out of moves.

--

Name: Katherine Frazer

Age: 29

Location: Brooklyn, NY

How/when did you begin working creatively with technology?

My parents told me that when I was a toddler, they used to wake up to the sound of the printer. I was printing drawings I made on the cracked version of Photoshop my dad installed over dial-up. I don’t remember this. I do remember being 9 years old and working on my first website, harvestmoon911.com. I was hand coding web pages and making graphics for the website layout. Not much has changed.

What did you study at school or elsewhere?

I double majored in Communication Design and Human-Computer Interaction at Carnegie Mellon University.

What do you do for a living or what occupations have you held previously?

I’m a full time artist. Previously, I was a product designer at several tech companies in both enterprise and consumer spaces. In a past life, I worked in research labs exploring collaborative online creation tools and social therapy robots.

What does your desktop or workspace look like? (Pics or screenshots please!)