“Are Drexciyans water-breathing, aquatically mutated descendants of those unfortunate victims of human greed? Have they been spared by God to teach us or terrorize us? Did they migrate from the Gulf of Mexico to the Mississippi River basin and on to the Great Lakes of Michigan? Do they walk among us? Are they more advanced than us and why do they make their strange music? What is their quest? These are many of the questions that you don’t know and never will.”

-Drexciya, The Quest, 2001

About a year ago, I was at Mood Ring in New York to see a couple of friends, some of whom were DJing that night and absolutely killing it. I don’t have much to remember the night by in terms of Instagram stories or pictures other than a video of me crying to an Aphex Twin track. If you’re born in and subsequently raised in southern Louisiana for 25 years, you rarely get a chance to listen to ’90s Cornish techno outside of the confines of your own headphones, but here it was happening. Later on in the night, something transcendent happened. My friend played the now-culturally minted bounce track “Gimme my Gots” by Shardaysha. The song begins with a harsh, prolonged root-tongue roll of an R, the kind that marks so many bounce songs. As we celebrated getting a little warmth of home on vacation, I began to really observe the crowd. Many of the bar patrons really didn’t know how to act. Some flailed; others did loose interpretations of Big Freedia music video choreography, and I think someone in the corner wound up screaming for 10 seconds until the beat dropped.

I’m a sucker for semantics. Definitions matter, and I like being on the same page. As I was working on this, I kept stumbling upon a frustration definition of Bounce music. According to Wikipedia, for instance, Bounce is not considered a dance genre, but a sub-genre of southern hip-hop. Certainly, in some ways, classification via an open source information website may not matter that much, but Wikipedia is still the go-to for information across the internet. This mundane discovery got me thinking: Why don’t we place New Orleans Bounce music within the lineage of American dance music? Regionally and especially in New Orleans, most parties start with the 90’s hits and flow into house and afrobeat, but any DJ worth their weight in the Crescent City will definitely end the night with a bounce shakedown– a “Bunny Hop” session if you’re lucky. Bounce has been deconstructing club music since well before Resident Advisor or Pitchfork heralded the genre’s onset. Unfortunately, the farther you travel from the Birdsfoot, New Orleans Bounce starts to fade from dance floors, eventually to the point of near-nonexistence. The shadow-banning of bounce from the continuum of Black dance music is glaring, despite its multilayered affinities with the electronic genre.

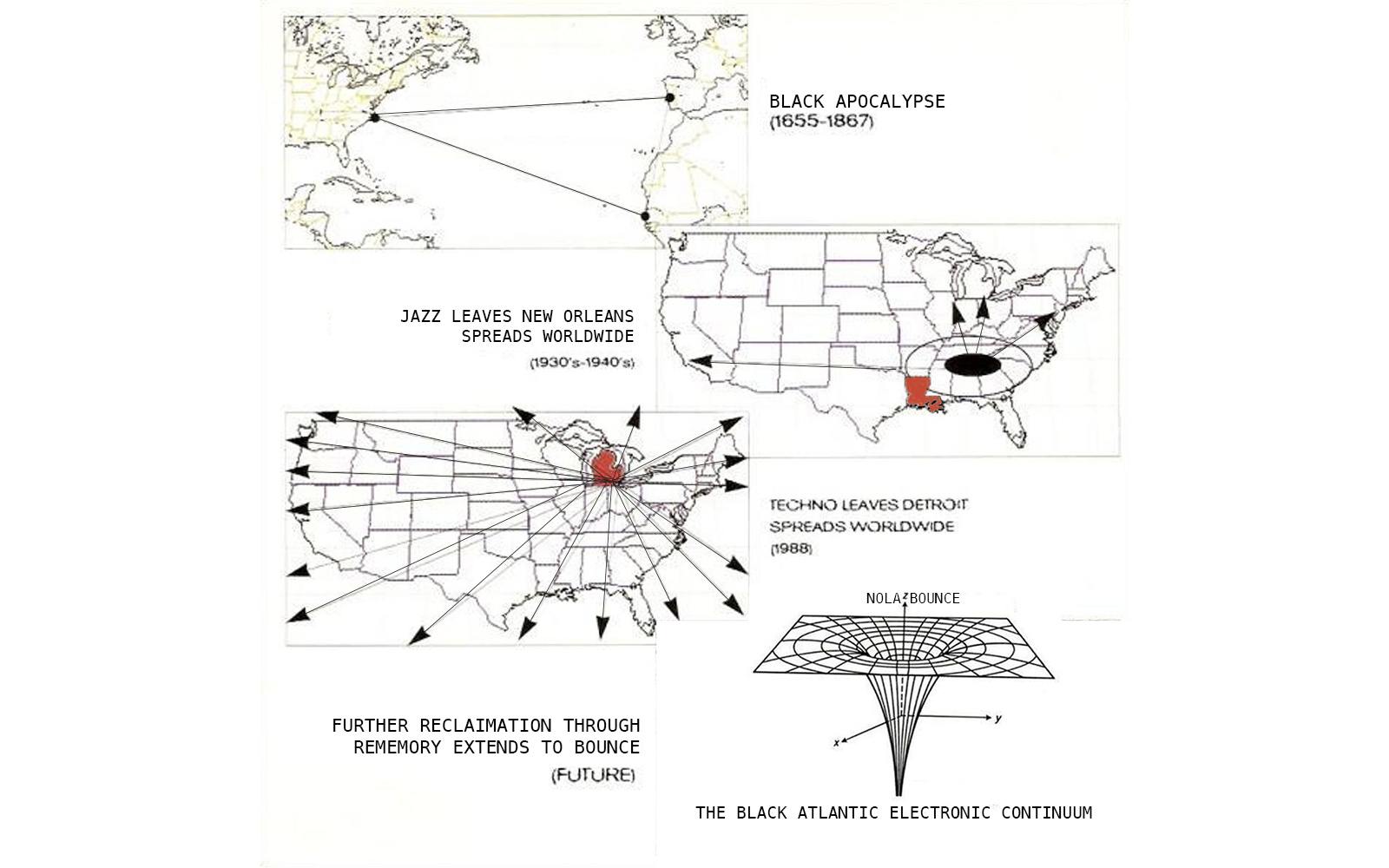

As a city, New Orleans has suffered from a generalized reverse hallucination with regard to its own history, a process that long precedes Bounce music’s conception. As New Orleans culture is being forgotten, so are our tangible products. And when something is forgotten, it’s often ripe for third-party revision. This concept is no better seen than in the exportation of Jazz as it spread throughout America in the early to mid 1900s. As suffocating de-facto and de-jure racist policies forced much of black life in the Mississippi Delta to Detroit, Chicago, New York, and California, new definitions and perspectives formed around what Jazz was. Since the great migration, Jazz music has found worldwide appeal via the music of Miles Davis, Dizzie Gillespie, and John Coltrane, and the like. Though touted as a wholly new form, the nascent genre bore strong relation to the sounds once heard in New Orleans’ Congo Square where enslaved Africans once communed. In 1819, British-American architect, Benjamine LaTrobe wrote some observations on the energy and machinations on Congo Square:

“An elderly black man sits astride a large cylindrical drum. Using his fingers and the edge of his hand, he jabs repeatedly at the drum head — which is around a foot in diameter and probably made from an animal skin — evoking a throbbing pulsation with rapid, sharp strokes. A second drummer, holding his instrument between his knees, joins in, playing with the same staccato attack. A third black man, seated on the ground, plucks at a string instrument, the body of which is roughly fashioned from a calabash. Another calabash has been made into a drum, and a woman beats at it with two short sticks. One voice, then other voices join in. A dance of seeming contradictions accompanies this musical give-and-take, a moving hieroglyph that appears, on the one hand, informal and spontaneous yet, on closer inspection, ritualized and precise. It is a dance of massive proportions.”

Congo Square gatherings took place Sunday mornings off and on from 1817 to 1885. Latrobe’s early observations of drum circles as their primary format make sense as in the beginning many of the musicians leaned heavily on the instrumentation they knew in West Africa. However, in a few decades’ time, Congo Square looked very different:

“groups of fifties and hundred… in different sections of the squares, with banjos, tom-toms, violins, jaw-bones, triangles and various other instruments… The dances are more fancifully dressed with fringes, ribbons, little bells, and shells and balls, jingling and flirting about the performers’ legs and arms, who sing a second or counter to the music most sweetly.”

What began as an energetic call and response drum circle evolved into a cosmic arkestra with an ocean of instrumentation and performances enrapturing the players and audience. Descriptions of 1830s Treme sounds not unlike the Spiritual Jazz movement in 1960s’ Oakland.

This is not to say that the world has forgotten New Orleans as the progenitor of Jazz, but as the genre continued to expand beyond the levee system, a historical revision of New Orleans’ place in its history was set in motion as well. The city has been robbed of its role as a hot-bed for new ideas and relegated to lukewarm reverence for what it created but cannot push forward. The city is revered for its history and deemed worthy of preservation, but is no longer upheld as a space for sonic progression. This recontextualization smooths out rich and complicated histories for the ease of commodification and misinterpretation. When it comes to jazz, a sort of reverse hallucination occurs here, refashioning the genre’s development so that emphasis is placed on its maturation through upwardly mobile diasporic movement instead of in continual and ongoing relation to the open wounds of the delta.

Bounce music finds itself subject to the same nursing home syndrome within progressive black music circles. That cursory search on Wikipedia delineates bounce music under the genre southern hip-hop, but if you head to any bar on a night here in New Orleans, you’ll quickly find that find bounce is more sonically akin to footwork than a 75 bpm riding track. This isn’t to say that bounce cannot be considered in relation to hip-hop. In fact, bounce is infinitely amorphous. Bounce is able to slow itself to the tempo of a “grown and sexy” daiquiri lounge and lie comfortably under Sade acapellas, but it can also escalate to the intensity of a speaker-bleeding, Limewire-quality Sissy Nobby track that sounds like someone recorded the last millisecond of an 808 short circuiting, tossed in the river and looped it endlessly.

Bounce’s historical treatment–like that of jazz–strips a sound and a people of its history. This process, however, also places New Orleans in a state of acceleration, constantly out of joint with its own time and with history. The city creates new technologies in its own rapidly decaying shadow. Black Accelerationism, or specifically “Blaccelerationism” as coined by Aria Dean, argues that black people have been living in a “post” environment since the Middle Passage in the 1600s. Fractured, scattered around the world, and forced to build cultures anew from leftovers and refuse Black people have become the culture d’jour for society writ large. Society shovels it back to us in degraded form– bounce tracks for TurboTax, and simulacral repatriations to the city. The hood is Babylon.

Due to its particular, ongoing ecological, infrastructural, and political degradation, New Orleans has accelerated even faster than many other cities not only throughout America but around the world. We don’t have the time. We’ve lost our land. Bedrock doesn’t exist. New Orleans has always-already lived in the after, and continually cycles through new potential visions of a final form. Beginning with the arrival of the first African slaves–brought by the French– at New Orleans’ port in 1710, and the city’s “founding” eight years later.

A nearly 300 year cycle ended early in the morning August 25, 2005 with water as its harbinger. Between 7:21 and 8:29 AM, gulf water breached the city’s levee system and overtook the Lower Ninth Ward and Lakeview, heading for higher ground. Many clocks stopped, inundated by the force of Katrina. These clocks formed a symphony of timelessness for the gulf coast as we knew it. A moment of silence for a city once afforded love, care, and resources now forgotten.

An aerial view of Isle de Jean Charles, LA

It is well-documented that the two months following the water’s breach were nothing short of a complete catastrophe. FEMA blocked delivery of emergency supplies to Methodist Hospital, turned away local doctors for not being in the right, actively blocked flights carrying private medical air transport, prevented the Coast Guard from delivering diesel fuel, and delayed all emergency supplies, vehicles, and equipment from other nations for months. (Elizabeth Williamson, “Offers of Aid Immediate, but U.S. Approval Delayed for Days,” Washington Post, September 7, 2005.) The complete lack of non-federal aid exacerbated existing problems as the Superdome had surpassed its capacity of 20,000 and all the displaced citizens it housed were moved to the Convention Center within one day. For both evacuee areas, there was no air conditioning or proper sanitation.

The acceleration towards the collapse of the American empire is something we’ve read about and probably felt in the past few years–especially since the 45th president’s infiltration of our collective subconscious and twitter-feed, but these anxieties have been torturing the American south for decades, and they came to a head during Katrina’s fallout. Environmental anxiety, climate change, political corruption, etc. are the ABCs of Louisianan culture. Many understand the notion of a post-environment conceptually but it’s a whole ‘nother story when it’s right before your eyes.

Taking the I-10 over the Pontchartrain leads you directly through the ruins of what once was. First you see the forgotten planks of an old path that farmers would lead cattle over to reach the city. Then, as you reach the lake bank, you transition into patches of lost earth; once a vibrant wetland now shrinking away into the muddy waters of the Bay where it first rose from over 100 years ago. This habitat is necessary for the survival of the diverse wetland species in our area, which are now migrating away to more stable lands or just going extinct. This, of course, isn’t due to the natural course of the earth’s processes. What we see in front of us is the swollen corpse of what oil and gas corporations have killed and placed at our feet. Past the barren mudflats lie the culprits: the many smokestacks and refineries at Exxon and Chevron off in the distance, proudly burning forever, vowing to choke us off until we are a people underwater.

This threat of a subaqueous existence brought by climate disaster not only appears to culminate a historical cycle for the city of New Orleans, but also marks a weird actualization of African diasporic water-myths, particularly the mythology of Detroit techno duo Drexciya. Told across track titles, sleeve illustrations, record engravings. and the music itself, the Drexciyan myth begins with the story of the Atlantic slave trade. In the middle passage, as Africans were being forcibly moved to the Western Hemisphere on colonizers’ boats, pregnant women decided to spare their offspring this life of absolute horror and jumped overboard. The women drowned, but their offspring, born with gills in place of lungs, survived; they became Drexcyians, the children of Middle Passage. They soon navigated their way to their new underwater home Drexciya where, using their intelligence and ingenuity, they developed their own technologies such as Wavejumpers. Taking influence from Paul Gilroy and his writings on the movement of the African diaspora breeding a cultural nationalism around the Atlantic Ocean, providing a form of unity regardless of how splintered black people are geographically, Drexciya (the musical group) created cultures, enemies, and an entire livelihood out of these traumatic beginnings. Mythology is a healing mechanism and the Drexciya story is no different, acting as a lighthouse for lost black souls.

As a revisionist history and speculative fiction, the Drexciyan mythology models a form of speculative acceleration as theorized by Kodwo Eshun. In “Further Considerations of Afrofuturism,” Eshun describes Afrofuturism as an “enigmatic returns to the constitutive trauma of slavery in the light of science fiction.” Reaching “a point of speculative acceleration,” these methods “[create] temporal complications and anachronistic episodes that disturb the linear time of progress . . . . Chronopolitically speaking, these revisionist historicities may be understood as a series of powerful competing futures that infiltrate the present at different rates.”

Drexciya follows in this tradition of post-historical (i.e. non-linear) myth-making, figuring the Drexciyans themselves as the cornerstone of various ends of the world. First, we find them at the beginning of the modern age as African were thrown overboard as capital, not humans, and central to a global economic revolution that seeded the logics of finance capital and modern insurance. But we also find Drexciya at another world’s end, this one specific to Detroit in the 60s through the 80s after the mass exodus of the city’s car manufacturing plants, which left the city resourceless for those who could not move to the suburbs. Though never explicitly named as such, Drexicya’s (the musical group) myth employs hyperstition as a therapeutic counter to the upheaval that characterized 1980s Detroit, transmuting fiction into truth, rewriting and folding history onto itself to narrate an alternative account of capital, struggle, and blackness in the new world.

By rewriting this history into a format that grants us power, we can move into a future with more tools at our disposal. Instead of a diaspora that sees itself akin to a shattered mirror, Drexciya provides a missing link through which we can see each other, and moreover see ourselves. The Drexciyan myth is nothing short of how a religion is spread and realized. To live in the world of Drexciya and within the shell of post-1968 Detroit (their own personal end of the world) exemplifies Paul Gilroy’s extension of DuBoisian double-consciousness in Black Atlantic as a “characteristic of post-slave populations in general.”

That between-ness that Gilroy describes is nothing new for New Orleans. In fact the terminology historically available to name these “fractal patterns of cultural and political exchange and transformation” are endemic to New Orleans’ culture–creolization, for one. In the Treme, many people’s heritage is hardly binary. Creoles, Cajuns, Quadroons, Passé Blanc, etc. There’s a natural risk of drifting, untethered, for those with such lineage. You have to attach yourself to something otherwise you’ll be pulled in so many directions, have your feet in so many homes, but all without the ability to lay your head anywhere. This blur is the defining characteristic of New Orleans and its music. Is Jazz classical black music? Is it folk? Is it noise (I mean that in a beautiful way!)? Bounce music finds itself within the same confusing continuum Jazz once did half a century ago. Is this “genre” party music? Is it minimalism? Is it for the cool down room? Is it for a cookout? Is it religious? Yes to all.

The conviction to stay firmly with the between runs deep in bounce music and its culture. The party bus where the party is always on the move, the samples and bpm speeding up or dropping off to the point where you can have two slow jams and a breakdown in the same song at the same time, . Songs like “Iberville” by Messy Mya, Sissy Nobby’s “Consequences” to Kortney Heart’s “My Boy,” and Shardeysha’s previously mentioned bop all confirm the total fluidity of the bounce backbeat.

Bounce also liquifies the boundary between what is generally understood as human and inhuman. Is that roll of the tongue the artist on the song? Is it an 808 snare? Maybe it’s a sample from some Carl Thomas deep cut or a voicemail from way back when Cingular was a thing. Hard to tell. This human-machine ambiguity is laid bare in Bounce, and this indeterminacy is one of the most radical notions I’ve seen in my time as a music lover. The Roland 808 drum machine is the match to the powder keg of black Atlantic music in the postmodern, late capitalist era. For bounce, electro, footwork, and techno, this machine is the canvas for which black expression was spread and queered across dance floors around the world.

Even further, bounce music and its culture incorporates an amalgamation of identities that many are still coming to terms with elsewhere, but that have long been the norm here in the Crescent City. Bounce, one of our biggest cultural exports, has for decades accepted genderqueerness, with people across the spectrum of gender expression shaking down and expanding ideas of what’s considered masculine and feminine. The music video for 1993’s "Jubiliee All” by DJ Jubilee shows tons of men in the music video read as traditionally cis and masculine, who end up twerking halfway through the video. Cheeky Black’s 1994 “Twerk Something” doesn’t discriminate in its call to action; the command to “twerk somethin” is universal. Before the more recent entrance of nuanced terminology around queerness into the mainstream, the position of “Sissy” and other forms of queerness circulated in the Magnolia projects uptown with little fanfare–though in the last few years, many queer New Orleans bounce artists have gone on the record saying that they find the term disrespectful to the genre as their music should merely be considered bounce music. The bending and widening of masculinity for Black men who usually find themselves shackled to the wall performing dancefloor stoicism in any other setting can enjoy some loose footwork in a second line and a shake if they so choose.

Bounce enacts the ethos of black music, being in a looped and literal dialogue with its past–the repetition as progression that characterizes so many black musical genres. From formal repetition within a given song like Juvenile’s 65 “Ha’s” to larger cultural-historical loops like the sonic and affective affinities between Congo Square gatherings, their modern-day recreations, and Thursday night Bounce only parties at the Dragon’s Den. Percussion shakedowns in the 19th century seep into the 21st. New Orleans is proud of this repetition as we eke out a future through our past.

Capitalism has trouble commodifying a snake happily eating its own tail. As most of bounce culture exists outside the purview of the mainstream music industry, most of these songs include well-known songs that would be nearly impossible to license samples for. With most bounce tracks refusing to conform to modern day music industry practices around sample clearance and intellectual property, it’s tough to get these songs into mainstream circulation. While this largely shuts bounce artists out of the market and due compensation, it’s tough not to feel pride in the genre’s refusal to bend to the RIAA’s will. Instead, New Orleans’ recent musical history exists primarily on sites like DatPiff, LiveMixtapes, and Youtube in an appropriately diffuse digital archive of vernacular diasporic culture after the internet.

New Orleans bounce has so much going for it, and it would be a waste just for it to be commodified and divorced from its origins like other genres, culture, and neighborhoods. It asks so many questions about how we perceive not just music but culture as a whole. Queerness, humanity, technology, it’s all up in the air here. There are no boundaries between the thematic, the performer, and the identity that appears onstage or in the crowd. Already too fast for radio and its listenership, acceleration is inherent to bounce music as technology and humanity are in lockstep as a means to dismantle the limits of what we have previously perceived to be dance/southern rap or any kind of music at all. Many black geographies hold unearthed myths and histories that we can look to as astronomical guideposts. At this time, whoever can sell the most commodified narrative of Bounce music controls its history and future. We can counteract this cultural sepsis; the city that care forgot only has to begin to remember.

Watch/listen to Care Forgot, a visual mixtape by Ryan Clarke. Special thanks to the Jules Cahn Archive at the Historic New Orleans Collection.

Care Forgot, a visual mixtape by Ryan Clarke

Ryan Clarke is based, born and raised in Louisiana. He’s currently studying for his doctorate in coastal geology at Tulane University. Intimately aware of the ways his home is at great risk of physical and cultural erasure, he finds way to quantitatively document this loss in his research and qualitatively with works that try to unpack the plethoric connections Black people have with the delta and its tributaries. Through the lens of Jazz, New Orleans Bounce, Detroit Techno, and Chicago House, he views the progression of technology and culture at-large as byproduct of Black innovation under a theory known as “Southern Electronics”.