Nick Pinkerton reviews 1995: The Year the Internet Broke, a screening series programmed by Screen Slate at Anthology Film Archives in March 2020. Cut short by COVID-19, the program lives on in the short publication produced to accompany it. Taking the program as a starting point, Pinkerton explores the internet-obsessed films of the mid-90s and their variously accurate visions of a digitally networked near-future.

A joke, loosely paraphrased, from a message board that I used to frequent while wasting time at my day job back in the mid-to-late aughts: “Every time I log on, I crack my knuckles and say: ‘I’m in.’” To get it, you’d have to be familiar with an entire set of tropes that had emerged during the mid-90s, when mainstream movies first started to visualize the internet and integrate it into narratives, more often than not as a gimmicky hook. For a brief moment, characters in studio films were suddenly talking about “hacking into the mainframe”—whatever the fuck that was. By the mid-2000s, this period already seemed remote; by then, the internet no longer plausibly offered the promise of out-of-the-ordinary adventure—everything implied in the once-popular habit of using the verb “surfing” to refer to hopscotching between links provided by a web directory—and had turned to, yes, something that was part of the furniture, something literally in the air, something banal that we used to waste time at work, with little expectation that it would rebuild the world for the better.

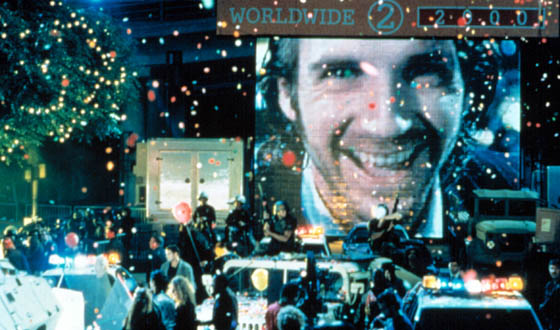

Hollywood’s brief, promise-filled love affair with the microprocessor was the subject of 1995: The Year the Internet Broke, a short retrospective series collectively programmed by writers at listings website Screen Slate that ended its run at Anthology Film Archives just as quarantine shuttered New York City. The series was comprised of six narrative feature films released in ’95—the same year that Jean-Paul Gaultier’s knitted circuit board collection hit the runway—each paired with a short, most of these abstrusely complementary experimental works by new media-oriented artists, including the likes of Jon Rafman, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Nam June Paik, and Faith Holland. In an inspired and perverse design decision, a slim companion book of essays available at the box-office reproduces several of the eyeball-straining palettes of early web design, including the nigh-impossible-to-bear green-text-on-black-backdrop in which my first film criticism was published online in 2003. The book opens with a quote which might summarize the premise of the series, from Emmanuel Goldstein in his review of Irwin Winkler’s The Net in the publication 2600: The Hacker Quarterly: “The summer of 1995 will be remembered as the year [sic] Hollywood discovered the internet.”

The films shown are occasionally prophetic, even, situationally, clairvoyant. The series was cut short by a single screening when Anthology shut down on the evening of March 12th in response to the CoVid-19 outbreak. What was lost was a Thursday night run of Robert Longo’s William Gibson adaptation Johnny Mnemonic, which begins with an on-screen text scrawl reading “SECOND DECADE OF THE 21ST CENTURY, CORPORATIONS RULE. THE WORLD IS THREATENED BY A NEW PLAGUE.” This was the night before a Rose Garden presser in which the chief executive calmed a panicked nation by obsequiously petting and fawning over a collection of incredibly morbid-looking pharmaceutical company CEOs.

Many of the films in the series stumbled into relevance, while all of them in one way or another land wide of the mark in how they envisage computerized living, now or in the future. If you were to nominate a single movie as the archetype of clunky net novelty cinema, you could do a lot worse than having The Net as your candidate. (The title, I might mention, is a double entendre.) The movie opens with a primer in the incredible efficacy of new technology, and the possibilities it presents for total social immuration and isolation. Sandra Bullock, playing a systems analyst who works remotely for a software company in San Francisco from her cozy redoubt in Venice Beach, lives through her computer in much the same way we’ve become accustomed to doing and are now forced to do by government regulation. She orders dinner via Pizza.net, checks into her flight for a planned vacation online, and socializes via a chatroom, where the first thing we hear is a text-to-speech voice belonging to someone named IceMan, pronouncing “No one leaves the house anymore. No one has sex. The net is ultimate condom.” Later, in a breezed-past moment, IceMan is revealed to be the screen name of a 12-year-old named Kelly. Much thinking about the internet at this period focused on the frightening possibilities of online anonymity; now of course the fear as much concerns living in public, and the potential for public dogpile shaming.

The screenplay for The Net was the work of John Brancato and Michael Ferris, who got the job on the strength of their then-unproduced script for The Game, made into a film by David Fincher two years later. Both films play with the same basic premise: The ease with which identity can be erased or compromised in a world where all information is online, or, as a frayed Bullock puts it: “Think about it, just think about it, our whole world is sitting there on a computer.” The films feature some of the same scenarios, such as proposing the problem of getting across the Mexican border without papers, and both even feature CNN anchor Daniel Schorr playing himself—the television journalist as actor, “fake news” before the coinage of the phrase.

Putting the two side-by-side is, among other things, an object lesson in the importance of having a real director on your movie. Nothing ages on screen faster than technology—Fincher’s The Game, which puts little emphasis on its tech aspects, still plays gangbusters today, whereas Pizza.net is a howler. Fincher’s film is also noteworthy for its application of game logic in a narrative context, something also explored in David Cronenberg’s 1999 eXistenZ which, like Gibson’s work, imagines logging on done via biotechnological modifications—literal everyday cybernetics like neuro-surgical implants rather than the practical cybernetics that, glued to our screens round-the-clock, we enjoy today.

eXistenZ (1995)

The Net director Winkler, an ex-agent and producer, came up through the Hollywood ranks, while the career of Brett Leonard, whose Virtuosity also played in the ‘95 Anthology series, was tied up with Silicon Valley and new computer technology to an unusual degree. The year after Virtuosity’s release, Leonard gave a presentation before an audience at a lab co-hosted by Creative Artists Agency and the Intel Corporation, concerning the future of interactive entertainment. (The presentation involved digitizing Danny DeVito.) Leonard had been living in Santa Cruz in the ‘80s, and there he fell in with the rising stars of tech, including Jaron Lanier, the former Atari employee who coined the term “virtual reality” and, in 1985, founded the first company to sell VR equipment, VPL Research, Inc. It was Leonard who would effectively break VR into the mainstream, incorporating it into his 1992 blockbuster The Lawnmower Man, adapted from a 7-page Stephen King story that had none of the film’s techie elements, with Leonard adding the element of VR, and Pierce Brosnan as a sort of sinister Lanier.

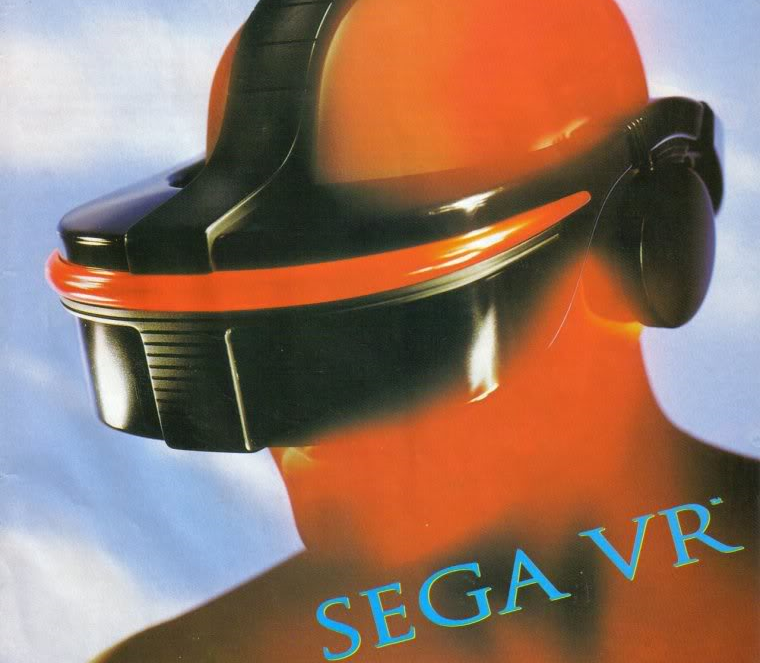

Leonard’s Virtuosity trots back to the virtual reality well, featuring Denzel Washington as an ex-cop serving out a prison sentence, sprung to beat the streets when the programmed serial killer that he’s been sparring with in an experimental VR training video, SID 6.7, manages to acquire a nanotech android body and sets out to wreak havoc IRL. Leonard gestures towards satire of bloodthirsty American media culture—an identifiable low point involves an arena full of gormless idiots chanting “Kapow” at a UFC octagon—but Paul Verhoeven he ain’t, and Russell Crowe, playing the peacocking SID 6.7 in his American debut, was lucky to slink away from this with his “promising young actor” tag intact. The film had none of Lawnmower Man’s success, leaving Leonard to move into new techie territory, namely 3D IMAX. (I can affirm that one of his efforts in this department, 1999’s Siegfried & Roy: The Magic Box, is at the very least transfixingly awful.) What was novel in ‘92 was a known quantity by the time of Virtuosity—the music video for Aerosmith’s “Amazing” featured Alicia Silverstone modeling VR goggles, Sega had tried and failed to get a VR system to market and, in ’95, Fox even trotted out a virtual reality-themed TV series, VR.5, that lasted all of ten episodes.

Sega VR advertisement

Sega VR advertisement

While the visual possibilities of VR for movies were already self-evident by ‘95, the stodgy, stationary keyboard still proposed a difficult problem. In The Net, one can see Winkler and cinematographer Jack N. Green struggle manfully to crack the riddle that has perplexed filmmakers since the dawn of the personal computer—namely, how to make something “cinematic” out of a person sitting and staring at a screen? In John Badham’s 1983 WarGames—the original whiz kid hacker film—the great DP William A. Fraker gets some good effects from showing Matthew Broderick’s face reflected in a monitor, this already presaged by Fraker’s shooting an entire scene in the glass of a honky-tonk Pong console in Frank Perry’s 1975 Rancho Deluxe (The same is done by Karl Kofler in Robert Dornheim’s 1983 Digital Dreams, an account of Rolling Stones bassist Bill Wyman’s love affair with his Apple II.) The Net’s not-entirely-satisfactory solution is to have Bullock anxiously narrate her actions at the keyboard (“Disc, disc, where are you?”), with some swooping zooms into password prompts, while for neither the first nor last time an instrument of suspense is made of waiting on a download bar to fill out. As internet access became less and less rarified, to the point of everyday banality, attempts to create dramatically charged browsing sequences moved away from the user and towards the screen. As early as 2000, you have something like Pierre-Paul Renders’s Thomas est amoureux—to my knowledge the first narrative film told entirely through the mise-en-scene of a computer monitor, in the fashion familiar from later desktop thrillers: Unfriended (2014), Unfriended: Dark Web, and Searching (both 2018).

A rather more adrenalized approach to the interface than that seen in The Net is taken by Iain Softley’s Hackers, another download bar nail-biter released in September of ’95, just over a month after Virtuosity. The film is the American debut for Brit Jonny Lee Miller, who the following year would appear as “Sick Boy” in Danny Boyle’s Trainspotting. Like that movie, Hackers exemplifies the jittery, pedal-to-the-metal hyper-stylization that was very much in the air at the time. Miller’s high school hacker Crash Override and the confederation of young console cowboys—and one cowgirl, played by Angelina Jolie—that he falls in with are speed junkies, getting around New York City by rollerblade, pounding proto-energy drink Jolt Cola, and seeking ever-faster processors. These early extremely online youths live at the speed of information, the internet seeping into their daily lives. Crash’s fantasies come in hot-shot, hyperlinked montage, and in the film’s opening, which has him arriving in NYC by plane, the towers of Manhattan seem to transform before his eyes into a circuit board as Orbital’s “Halcyon + On + On” pumps up under the title card. Crash may have an oversized Nirvana poster on his bedroom wall, but the soundtrack here is all electronica and house, an association of sound and subject matter that would run through a great many cyberthrillers.

Hackers (1995)

Hackers (1995)

In Hackers, getting online is a trip, a dopamine rush: Crash and friends can be seen bathing in the “million psychedelic colors” of a state-of-the-art laptop’s active-matrix display, while their hacking exploits plunge the viewer headlong into a modeled cyberspace or the stacks of a compromised supercomputer belonging to a multinational mining company. (Its towers, aptly enough, resemble impersonal, undecorated Skidmore, Owings & Merrill-style corporate skyscrapers.) Hackers, it’s worth noting, was released in the same year as Larry Clark’s Kids, and takes place in approximately the same milieu, that of a diverse group of New York City high schoolers living rich, independent lives that are largely hidden from their parents and are grounded in subculture participation—skateboarding in Clark’s film, hacking in Softley’s—though two films couldn’t be any more tonally dissimilar otherwise. (Both movies also feature club scenes, somewhat de rigeur for the computer-driven film of the era—the Hackers kids congregate at Cyberdelia, Virtuosity has an interminable nightclub hostage sequence at a club called “The Media Zone,” and Kathryn Bigelow’s Strange Days, also in the series, features Juliette Lewis performing P.J. Harvey, and had Aphex Twin DJing Detroit techno on-location at its climactic millennium rave.) Hackers finally shares more DNA with the same year’s Empire Records, both very much glossy pop pictures chasing counterculture cool, though in the case of Hackers this is undertaken with apparent earnest interest in the then-current techno-utopian dialogue—screenwriter Rafael Moreu was inspired by attending a 2600-organized meetup in New York and hackers Tristan Louis, Kevin Mitnick, and Nicholas Jarecki consulted on the film.

The belief in borderless cyberdelic utopianism of the sort exhorted for by Hackers wasn’t to be long lasting. Per a conversation between hackers kejace and iostat included in Screen Slate’s booklet, our future belongs to the film’s corporate hired-gun heavy, The Plague, not the ragtag band of kids allowed to take him down. And in point of fact, most of the films in the series hew closer to a dystopian line that was part of speculative sci-fi from the jump.

One name from the annals of dystopian fiction has an outsized influence on these films, either directly or otherwise. In The Net, Bullock’s character’s mixed drink of choice is a Gibson; in Hackers, the supercomputer mainframe is The Gibson. The reference, in both cases, is a fairly obvious nod to the don of cyberfiction William Gibson. The visualizations of the internet in Hackers owes quite a bit to Gibson’s “matrix” cyberspace introduced in his 1982 short story “Burning Chrome” and further detailed in the novel Neuromancer. Gibson’s navigable, gravity-free landscape, in which data has a physical presence, remained the go-to for visualizing cyberspace even when the less glamorous future of GeoCities and Angelfire had practically arrived. Faith Holland’s RIP Geocities (2011), which played before Anthology’s screenings of The Net, sews together a number of images of wormhole internet as imagined through CGI and modelwork, from Winkler’s movie, Hackers and The Lawnmower Man. All of these belongs to a period when the internet was popularly visualized as a carnival thrill ride that would blow back your hair and blow your mind, rather than what it would become—an interminable cascade of e-mails and a handful of social media platforms that you numbly flick through while waiting around to die.

_N8gOFFq.jpg)

Faith Holland, RIP Geocities (2011)

Gibson’s cyberpunk aesthetic had already been borrowed from wholesale by the 90s, fodder for role-playing games made into 16-bit cartridges (Shadowrun), Billy Idol albums with special edition digipak (1993’s Cyberpunk, for which Leonard shot music videos), even fodder for over-the-top parody (in Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash). Johnny Mnemonic, however, was the first official Gibson adaptation, from the author’s own screenplay, based on his short story of the same name, first published in 1981 in the science fiction magazine Omni. Here, three years before the publication of Neuromancer, most of Gibson’s universe was already in place: the megalopolis concatenation of the Sprawl, the ultra-powerful corporate fiefdoms fighting proxy wars through yakuza hitmen, the cybernetically-modified “street samurai,” and the hired-gun hackers.

The work of world-building has been done, but the process of transposing it to film is another thing entirely. Longo’s completed film is one of those movies that sounds more fun than it is. To say that Johnny Mnemonic is a movie in which a cyborg dolphin named “Jones,” formerly employed as a Navy code-cracker and now living in a vat on a fortified bridge somewhere in Newark, uses satellite dish-amplified psychic force to immolate a raving eschatological street preacher played by Dolph Lundgren, is technically 100% accurate, but the conceptual lunacy, alas, never finds an analog in the filmmaking.

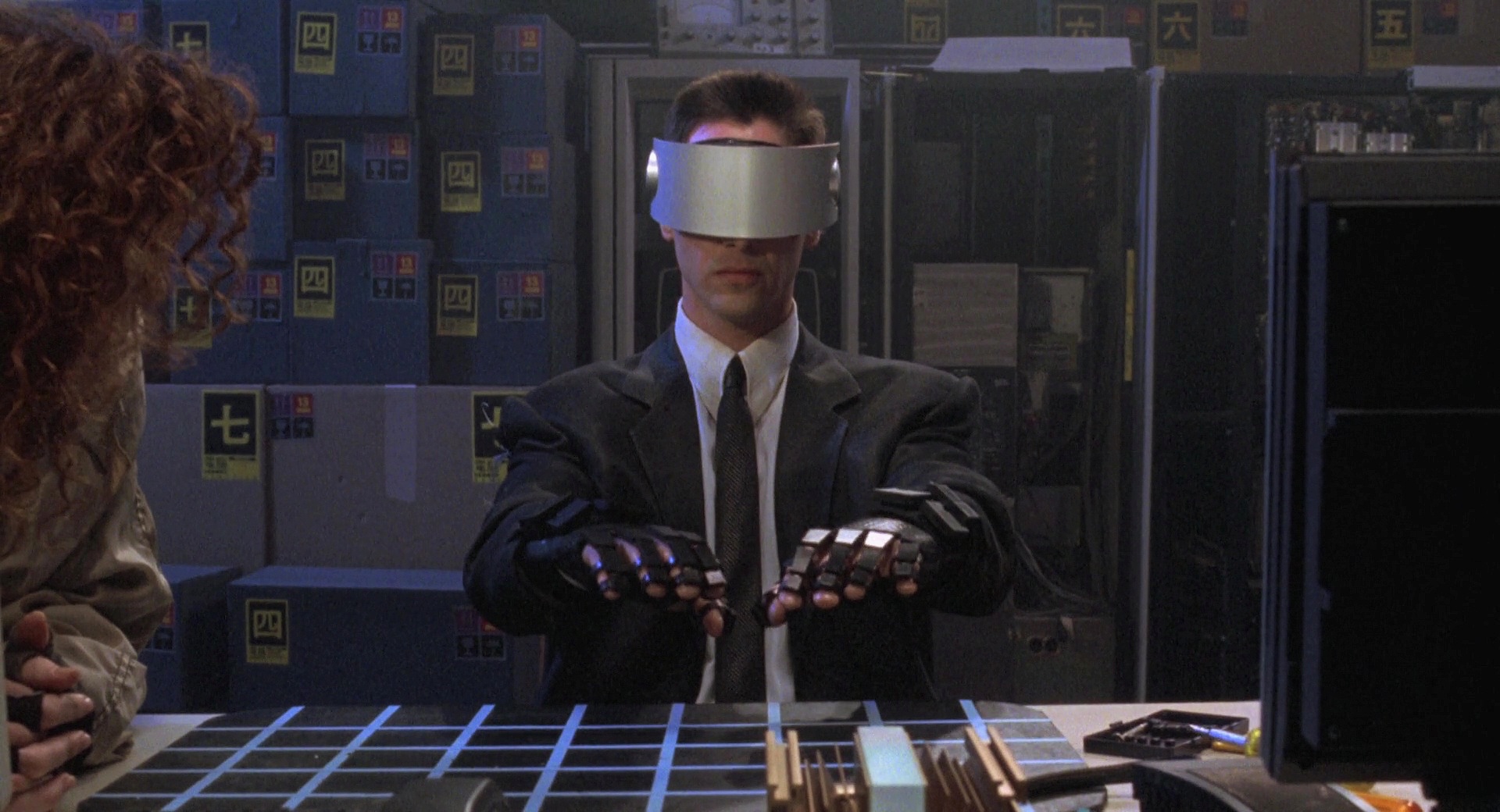

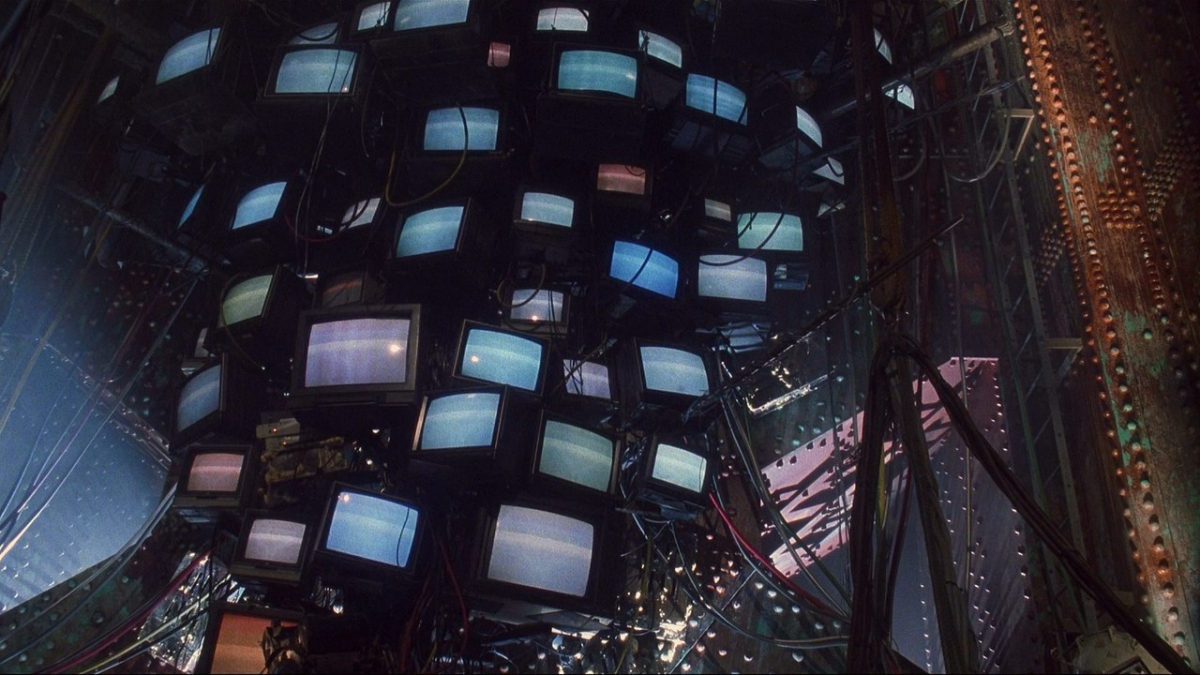

It needs be said that Longo was an odd fit for a would-be blockbuster, which is what Johnny Mnemonic, first conceived of as a mid-budget genre piece, eventually became. Longo was an occasional music video director and ‘80s art world star best known for his “Men in the Cities” series of large-scale drawings depicting sporty yuppies caught in mid-thrash—his stated inspiration was the dance of death that concludes R.W. Fassbinder’s The American Soldier (1970). Johnny Mnemonic was Longo’s first and last feature film, and he seems more comfortable with matters pertaining to art direction than with handling actors. Reeves, playing a “mnemonic courier” who’s had his childhood memories extracted in order to make room to carry filched corporate secrets, is at his most stilted; Dina Meyer without the necessary steel as his partner and hired muscle, Jane—in the original story the character was “Razorgirl” Molly Millions, a recurring character in Gibson’s fiction, but at the time the rights to Molly were tied up elsewhere. The movie, however, shares production designer Nilo Rodis-Jamero with Virtuosity, and he manages a couple of interesting touches, including a tower of tube televisions that’s like a Tower of Babel by Naim June Paik, whose 1986 Bye Bye Kipling was paired with Longo’s film.

Johnny Mnemonic (1995)

Gibson may have predicted our present pandemic—his NAS, or Nerve Attenuation Syndrome, comes of exposure to omnipresent technology, as some would have it that our predicament today is the fault of 5G towers—but he didn’t imagine cell phones in the future, an absence that would be even more glaring in 1995 than it was when his Neuromancer was published in 1984. Par for the course with cyberpunk films from Blade Runner (1982) on, Johnny Mnemonic imagines an East Asia-oriented near future. The story begins in Beijing, and actor/director Takeshi Kitano plays a Yakuza higher-up, given significantly more screentime in the film’s Japanese release version. in fact, the movie might’ve been enlivened by paying more attention to the pop sensibilities then emerging from Asia. The sclerotic handling of the action is confirmation of just how much, by the mid-90s, North American action movies that had lost sight of their own tradition of classical clarity, and needed to be revivified by an infusion of energy from Hong Kong—as happened when the Wachowskis hired venerated HK filmmaker and fight choreographer Yuen Woo-ping to work on their The Matrix (1999), a film whose debt to Gibson has been amply discussed.

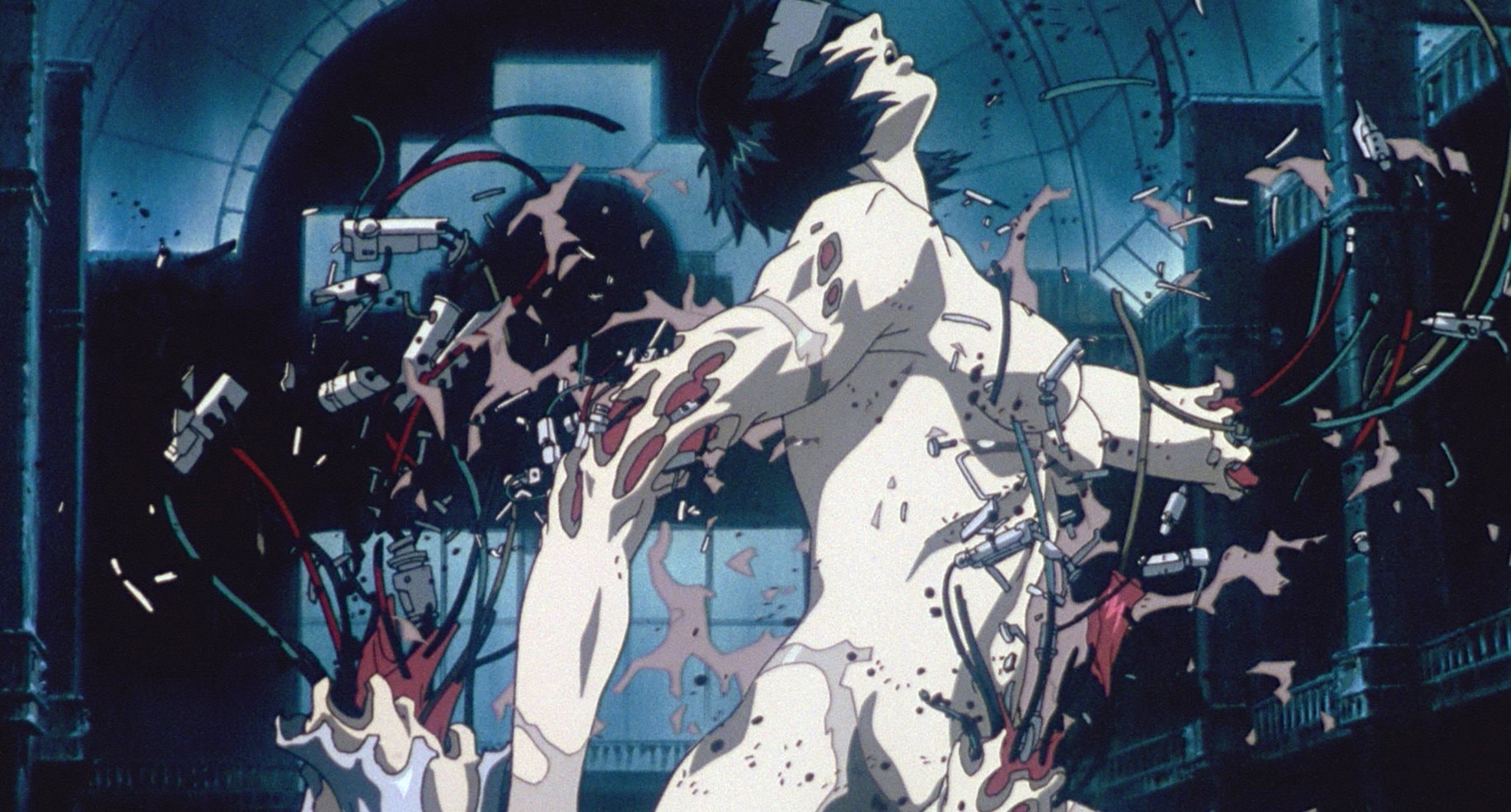

Many others joined Gibson in exploring the terra incognita of the new digital world in the ‘80s and ‘90s. Per a Los Angeles Times piece hyping the release of the ultimately ill-regarded Johnny Mnemonic: “the cyberpunk blend of technological literacy and social subversion is coming into its own as a cultural force—and moving into the mainstream.” The belief that a certain long-gestating underground aesthetic was getting ready to surface in the mid-‘90s was widespread. This aesthetic had no single author, but seemed to, like Pop Art, be shaping up in several places at the same time—while in the weeds writing Neuromancer, William Gibson was put into a mess of self-doubt by the sudden appearance of Blade Runner, the production design of which seemed to anticipate in near-entirety the world he had been privately and obsessively developing. Around that same time, in the beginning of the ‘80s, the first works were appearing from manga artist Masumune Shirow, whose 1989 Ghost in the Shell would be adapted six years later into a feature anime by Mamoru Oshii. Shirow was, seemingly independently, working along parallel lines to his approximate contemporary Gibson, whose work didn’t appear in translation in Japan until the mid-‘80s. Oshii’s Ghost in the Shell film in turn became an international cult item straightaways, first in Japan and then in the U.S., where it was released in spring of ’96, and was to be namechecked in due time by the likes of James Cameron and the Wachowskis.

Ghost in the Shell (1995)

Ghost in the Shell (1995)

Both Gibson and Shirow imagine a future populated with cybernetic or synthetic bodies–in particular female bodies, following a long lineage that can be traced through Auguste Villiers de l’Isle-Adam’s 1886 novel The Future Eve, the figure of the Maschinenmensch Maria in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927), and the cyborgian aspects of Roberta Breitmore, the fictional persona developed by artist Lynn Hershman Leeson since 1973. (Leeson's 1994 Seduction of a Cyborg screened before Ghost in the Shell at Anthology.) Ghost’s femme cyborg, fitted with neuro-surgical implants of her own, is Motoko Kusanagi, an agent for Public Security Section 9, on the trail of a mysterious hacker called the Puppet Master who is eventually revealed to be the creation of another Security Section turned sentient. As in Gibson’s cyberpunk narratives, we see the master’s tools turning against him: In Johnny Mnemonic it’s the uploaded apparition of the deceased founder of corrupt corporation Pharmakom; in Neuromancer, it’s the super-AI Wintermute.

Prior to the completion of Johnny Mnemonic, Gibson had struggled for years to get film projects off the ground—and it would be a few years until the first Gibson movie appeared that got the spirit of the source material, Abel Ferrara’s New Rose Hotel (1998), a bargain-basement production using b-roll from Ridley Scott’s Black Rain (1989) to stimulate a Tokyo setting, and that played up the vague-yet-profound sense of loss at the core of Gibson’s work, and Ferrara’s. (Heartache surrounding an ellipsis of a lost memory and tech fetishism, both of which play their part in Johnny Mnemonic, are driving forces in Ferrara’s 1997 masterpiece The Blackout.) One very promising prospect was Gibson’s screenplay from his 1982 story “Burning Chrome,” which as of the late ‘80s was slated to be directed by Bigelow—like Longo, an art world crossover into cinema, who’d trained in painting at the San Francisco Art Institute and the Whitney’s Independent Study Program, and palled around with Vito Acconci and Richard Serra. The film was never made, but some years later Bigelow would be responsible for Strange Days (1995), an end-of-the-century movie fairly splitting at the seams with ideas, executed with power and passion, and a work which increasingly looks like one of the most inspired American pictures of the 1990s.

Strange Days (1995)

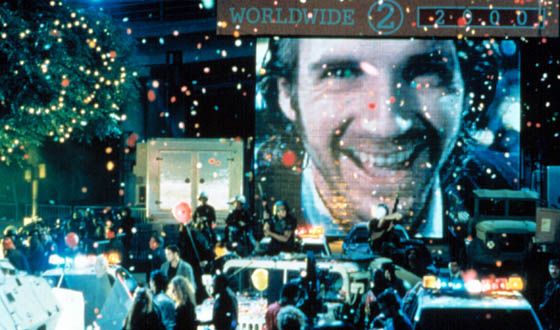

Strange Days takes place in the comedown countdown to the millennium, in a Los Angeles on the precipice of fall-of-Rome bedlam. Its central character, Ralph Fiennes’s Lenny Nero—get it?—is an ex-cop who now hustles a living dealing in contraband SQUID recordings: real-as-life first-person impression of audio-visual-sensorial data burned to MiniDiscs that can be played back through a scalp-mounted deck, which gives the “viewer” a firsthand experience of various adrenaline-rush experiences, mostly of a sexual or extralegal nature. In short, it’s VR with all of its still-unsolved haptic issues worked out. An archetypal noir hero, before being drawn into the line of fire by a woman in distress Nero is a small-time chiseler and a nightly tippler introduced nursing an old heartache, replaying his scuppered relationship with the Lewis character through a shoebox full of SQUID discs. (The title presumably comes from The Doors album and song, which includes the lyrics “We linger alone/ Bodies confused/ Memories misused.”)

The SQUID videos, shot with a customized, streamlined 35mm Arri, are eerily predictive of the now-ubiquitous GoPro/bodycam/POV porn aesthetic. The movie’s bravura opening is a SQUID-eye view of a restaurant robbery gone awry that ends when the fleeing perp wearing the headset loses his grip on the end of a building and plunges to his death. The evocation of the opening of Hitchcock’s 1958 Vertigo is, I suspect, not accidental, for Bigelow’s film shares its core preoccupations: the melancholy of memory, voyeurism, and the male gaze, now augmented by new state-of-the-art technology.

To this, Bigelow, working with the 1992 Los Angeles riots still a very-recent memory, adds the issue of race. Nero and his best friend, limousine driver “Mace” Mason—a fantastic Angela Bassett, with what one might consider the Barbara Bel Geddes role—are drawn into a conspiracy that involves an attempt by two LAPD cops to cover up their cold-blooded execution of a politically militant rapper, Jeriko One. (Released in October of ’95, Strange Days predated the murder of Tupac Shakur by nearly a year.) I last reviewed Strange Days shortly after seeing Bigelow’s Detroit (2017), simply because I couldn’t believe that someone could make one movie so complex and one movie so simpleminded dealing in essentially the same subject matter: the ethics of bearing witness, the complicity of voyeurism, and both the capacity and limitations of moving images in transferring trauma. (I write as, in still-recent memory, Alejandro González Iñárritu was purporting to allow posh Cannes patrons to experience a furtive crossing of the U.S.-Mexico border with his 2017 Carne y Arena, a VR “experience”—what the gear’s simpleton salesmen insist on referring to as an “empathy machine.”)

Strange Days was co-written by Jay Cocks and Bigelow’s ex-husband Cameron, whose career is defined by a double-edged technophobia and technophilia. Some years later Cameron would cite Ghost in the Shell as an inspiration for his Avatar, whose title nods to gaming and online lingo—Stephenson’s Snow Crash is credited with popularizing the term as referring to virtual online presences—though Strange Days is a far more penetrating and troubling investigation into the permeation of game logic into everyday life. Bigelow’s fin-de-millennium film straddles the divide between the 20th century, the century of cinema, and the digital future. Strange Days refers back to the key texts concerning the ethics of the cinematic gaze—Vertigo, yes, with a touch of Michael Powell’s sublime snuff-killer sickie Peeping Tom (1960)—while recognizing at the same time that we were entering uncharted waters. This was to be a world of ubiquitous, almost second nature image-making, in which Christopher Isherwood’s turn of phrase, through his author surrogate narrator in 1939’s Goodbye to Berlin—“I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking”—would come to a kind of literal fulfillment.

But even images caught in a passive, unthinking lens—if we allow that such a thing exists—offer a weighted perspective, and part of what Bigelow is compelled to imagine here are the possible side-effects of the sudden availability of so many subjective point-of-view perspectives. Technology is responsible for unleashing a sickness in Strange Days, as in Johnny Mnemonic, but its symptoms are first psychological, rather than physical: one of the film’s primary villains is a music mogul played by Philo Gant, a SQUID junkie for whom kicks just keep getting harder to find. Where much of the dialogue in the ‘90s revolved around the concept of what would eventually be dubbed digital dualism, proposing a hard barrier between the online anonymity and the “IRL” self—“Anybody can be anything in cyberspace!”—Strange Days shows a world where such boundaries have crumbled, where SQUID videos don’t just document real-life events, but incite them.

Video games and iPhones didn’t bring the POV shot into narrative cinema—there’s a lineage of roving stalker POVs that leads from Paul Leni’s The Cat and the Canary (1927) up through a whole host of giallo thrillers into the opening of John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978)—but they certainly brought about a sort of renaissance for it. From id Software’s launch of gore-soaked first-person shooter Wolfenstein 3D in 1992 it is a short hop to the POV shoot-out in Virtuosity, or the apotheosis of insipid play-throughs like Ilya Naishuller’s Hardcore Henry (2015) and Sam Mendes’s 1917 (2019). And from there to the police bodycam that allows you to live and re-live University of Cincinnati police officer Ray Tensing murdering unarmed citizen Sam DuBose in cold blood, or the massacre at the Masjid Al Noor mosque in Christchurch, New Zealand, captured and livestreamed by killer Brenton Tarrant’s helmet-mounted GoPro.

I don’t know what a diet of such images does to us, or what the internet has done and is doing, though I expect in the main it has not always been good—for some time after the New Zealand massacre, as a reminder of something or another, I kept on my desktop a screengrab from an 8Chan thread discussing it, an anonymous comment reading “It was like this pretty much to me” accompanied by a still from POV shoot-‘em-up section of Andrzej Bartkowiak’s 2005 film Doom, adapted from the first-person-shooter game of the same name, with a foregrounded gun being brandished by a ravening hellspawn. Very few films bother to pose these questions intelligently today, but Bigelow did twenty-five years ago. Her Strange Days hasn’t aged a minute, I’m sorry to say.

Nick Pinkerton is a Cincinnati-born, Brooklyn-based writer focused on moving image-based art; his writing has appeared in Film Comment, Sight & Sound, Artforum, Frieze, Reverse Shot, The Guardian, 4 Columns, The Baffler, Rhizome, Harper’s, and the Village Voice, among other venues. Publications include monographs on Mondo movies (True/False) and the films of Ruth Beckermann (Austrian Film Museum), and a forthcoming book on Tsai Ming-liang’s Goodbye, Dragon Inn (Decadent Editions).