Notes from Quar is a series that features diaries, playlists, musings from members of the Rhizome community while under COVID-19 quarantine. Here, Xin Liu of slow immediate reflects on her experiences distributing PPE in New York as an organizer of N95forNYC. Previously, Brud founder Trevor McFedries shared content from the far corners of the econ-web and other miscellanea.

April 9, 2020

Home in Brooklyn

When does my pandemic story start? I was still at Sundance when I started following tweets from Xiaohang, a woman my age living in Wuhan whose family was devastated early on by COVID-19. Fast-forward four months, and I’m self-isolating in my Brooklyn apartment, my personal and professional life upended, spending half my day organizing volunteers in New York to deliver donated personal protective equipment (PPE) to frontline health workers. Beginning in January, my memory forks in two timelines: one in China, one in the US.

The last week of February, right after Frieze Los Angeles, I went on a birthday road trip with two friends, Emilia Yin and Tiffany Xu. We drove from LA to the Grand Canyon, eager to see nature and land art, and hoping that the isolation and distance would provide a much-needed break from art fairs and festivals. I had a perfect birthday night in the mountains, with a tiny cake and one sparkly candle. We drank beer and sang songs in our motel room till late.

As we started back the following day, our phones buzzed with notifications from the Los Angeles Times, announcing that a Korean flight attendant who had landed in LA a few days prior had tested positive for COVID-19. She had reportedly dined in Koreatown. Emilia and I were a bit shaken by the news. Minutes later, a Chinese friend in New York messaged that she had found some 3M N95 masks available at $5 each. This was more than double the normal price, but I was nervous enough already and bought 15 on the spot. Arriving in LA, we stopped at a CVS before heading back to Emilia’s place. The shelves were already emptied of surgical masks, and only gloves and alcohol wipes were left.

At that point, even though the numbers of infections were growing dramatically each day, the public was still taking a wait-and-see approach. From China, my dad started sending me daily updates on US confirmed cases. I flew to Orlando on March 6 and Denver on the 9th, both for work, and he worried that I was not taking the matter seriously. I couldn’t explain to him why the public in the US seemed convinced that the imminent pandemic was just another flu season, but I started taking regular masked selfies to assure him of my diligence in self-protection. Out in the city and at the New Museum’s NEW INC, the 50-person co-working space where my studio is located, Gershon (my partner) and I were the only two in masks, which still felt embarrassing.

The reality finally hit on March 12th, when major museums, libraries and public spaces in the city all closed in a span of 24 hours. The notice we got from the New Museum predicted a 2-week closure. We were not so optimistic, so Gershon and I decided to move most of our essential studio materials and equipment out and prepare to “work from home.” On the evening of the 14th, Gershon's sister came over and picked up three N95 masks from us. Everyone had dinner together and then we separated.

On March 15th, the two of us officially began our "shelter in place.”

In the first week of quarantine, I was thrilled about the rare leisure time: planting flowers and vegetables, planning reading I had long put off, movies, regular exercise, and variety of virtual social activities (Animal Crossing fans add me!). But on the morning of the 22nd, I felt unwell and unusually exhausted. Later that night, I developed a low-grade fever. Both of us got quite nervous. Gershon moved to the living room and slept on the couch. I turned up the heat in the bedroom and spent the night alone. Fortunately, the fever subsided on the following day, and the other symptoms were only congestion and exhaustion, with no dry cough or chest tightness. We were still very vigilant. We slept in separate beds throughout the second week, and there was rarely any physical contact. I didn't have much interest or mental space to read books anymore, and passed time staring at the ceiling or playing video games in bed. That’s when Echo Yu of Fou Gallery sent me a WeChat message and asked if I had some spare masks. She had read about the extreme shortage of PPE facing New York, and was looking to collect masks from the Chinese community to donate to hospitals. Two days later, she told me that she decided to assemble a small team to import PPE from China for New York. This was not a new idea for us. Earlier in the year, Chinese people living abroad had organized huge donations of PPE to Wuhan. It was the same plan again, just in a different direction. Still mostly confined to bed, I decided to join them. The team quickly got to work, decided on the name N95forNYC and a visual identity, and launched our GoFundMe.

N95forNYC's GoFundMe fundraising page (April 10, 2020)

None of us had worked in supply chains or medical supplies before. But in the past few months we had read enough news reports online to understand the critical needs of frontliners facing COVID-19. The US-standard N95 respirator mask that blocks at least 95% of 0.3-micron airborne particles is the most crucial tool for individual protection. We researched for suppliers in China through personal networks, asking friends, friends' friends, friends' cousins……. I stayed up till very late several nights in a row, talking to people back home. The cost of N95 masks had already surged dramatically, and there were long lines of buyers outside the factories every day. To secure the stock, RMB payments in the full amount were required on the spot. All this chaotic bargaining would take place in the afternoon in China, or anywhere from 1am to 4am in New York. One night I held my phone while half asleep till the morning, waiting for my on-the-ground contact to call me to confirm payment. Later, Fou Gallery partner Wan Qiao would find a more reliable supply company to work with, and the orders would stabilize. Throughout, Echo continued finding forgotten back stocks of PPE throughout North America.

In addition to the N95 standard, there is another standard called KN95, which is set by the Chinese government. Standard-compliant KN95 respirators are functionally equivalent to N95, and are available from more suppliers. However, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Centers for Disease Control (CDC) have strict controls on the import, export, and use of medical supplies. Although these restrictions have been relaxed slightly during the pandemic, major hospitals in New York City still require medical personnel to wear CDC-certified N95 masks for liability reasons. As a result, many KN95 masks donated to hospitals by individuals have been backlogged and have not reached medical staff. In addition, many public hospitals and small clinics are far from government subsidies (such as Elmhurst, Woodhull, Jacobi, NYP Queens, Bronx Lebanon and St. Barnabas) . As more people started digging into these issues, I joined several COVID-related WhatsApp groups. The dearth of reliable information and loose structure of the groups made everyone's efforts feel a bit frantic. I was irritated by the lack of progress and wanted to do something myself.

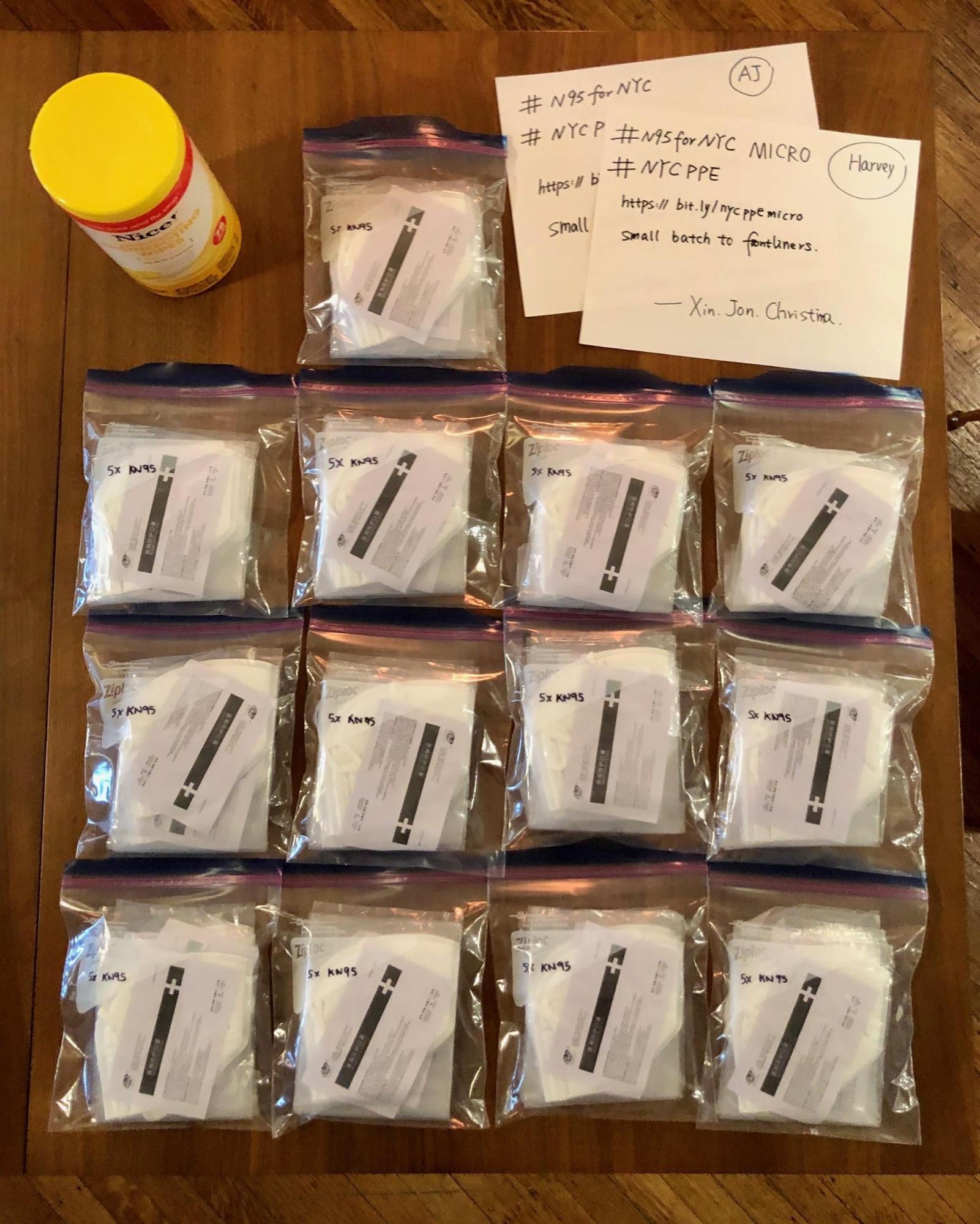

My parents are both doctors. When my father saw news of the outbreak in the United States in early March, he got so concerned that he sent 100 KN95 masks to me. Two weeks later, on the 26th, the masks arrived in Brooklyn. When he shipped them, I was still feeling awkward about wearing the extra gear, but the price of a 3M N95 mask in Chinatown had already surged to $15 USD.

Masks sent by my father, packed in groups of 5 for distribution.

Looking at the masks my dad sent, I felt certain that these 100 individually packed KN95 masks with certifications and seals in Chinese would not be accepted by hospitals. The only way they would find immediate use on the front lines was if I donated them directly to front line workers. I figured that once the respirators were in medical workers’ hands, they could decide what to do, if not just wear the masks on their commutes to work. I posted that I had respirators to give away. That night, a nurse from the Bronx contacted me through the WhatsApp group, and then drove to my house in Brooklyn. For a no-contact handoff, we put 15 of the masks in a ziplock bag on top of the mailbox and moved away. As she backed towards her idling car, masks in hand, she started to cry.

With that, I started distributing my remaining 85 masks, and others that Chinese friends quickly began sending my way. As the pace of donations from friends increased, I recruited a few delivery volunteers through social media and formed a “micro-batch” distribution team. We focused on delivering the PPE directly to frontline individuals, as I had done before. My friend Christina Xu helped me build an online system using a service called Airtable, incorporating a request form, delivery status, volunteer information, and recipient data. The delivery process quickly transformed from WhatsApp chaos to an efficient end-to-end system (thank you Christina!): the #NYCPPE initiative. In parallel, Echo’s group, N95forNYC, kept their team small and nimble. Having followed the events in Wuhan, the majority-Chinese N95forNYC team knew that other types of PPE besides respirators would soon be in short supply too, and bought medical coveralls early on. Frontline needs, federal regulations and our teams’ capacity were changing every single day. By the end of March, supplies from several of the COVID-19 response groups finally began to arrive at JFK.

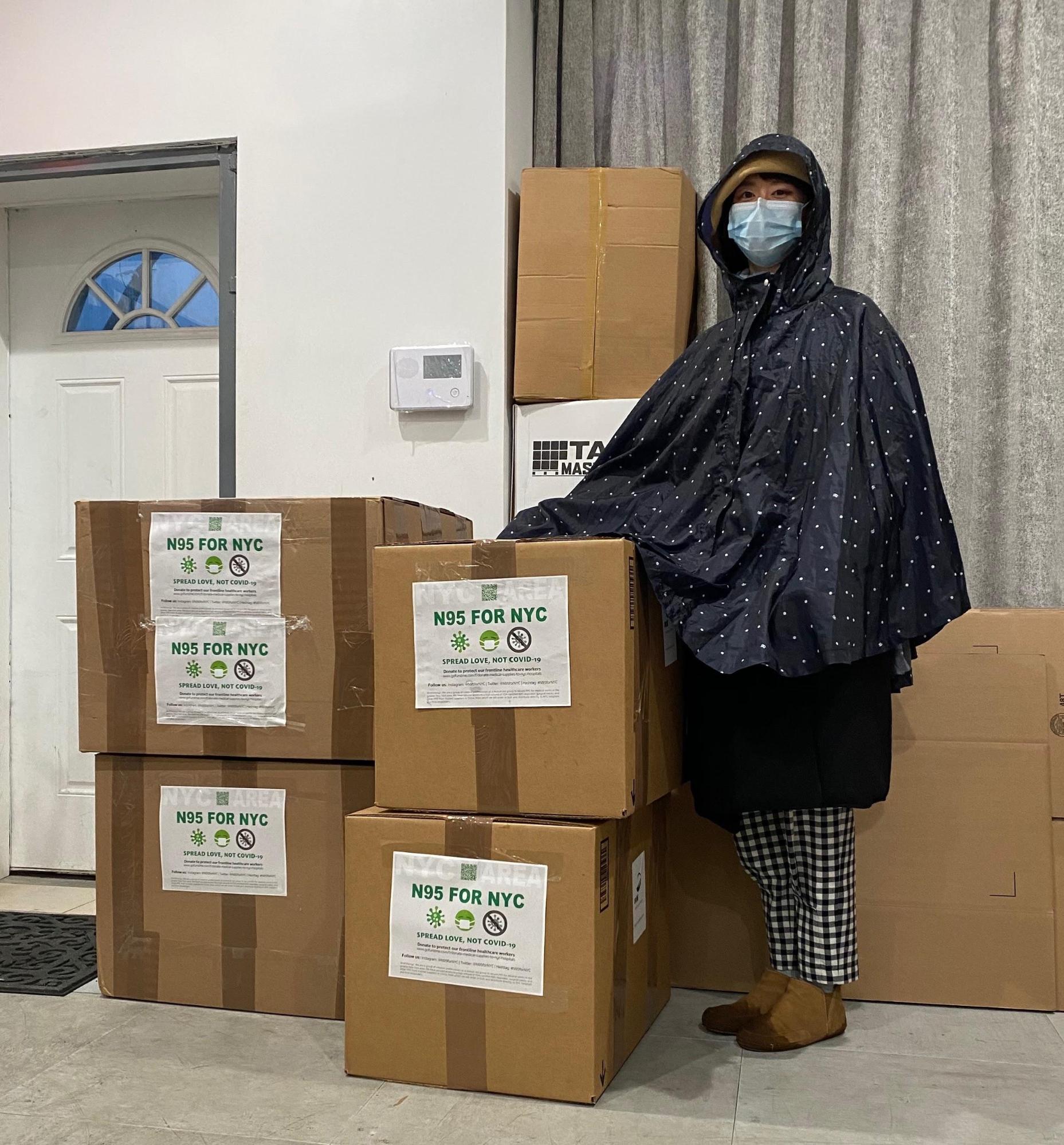

Echo He delivering medical coveralls to doctors in Flushing, Queens

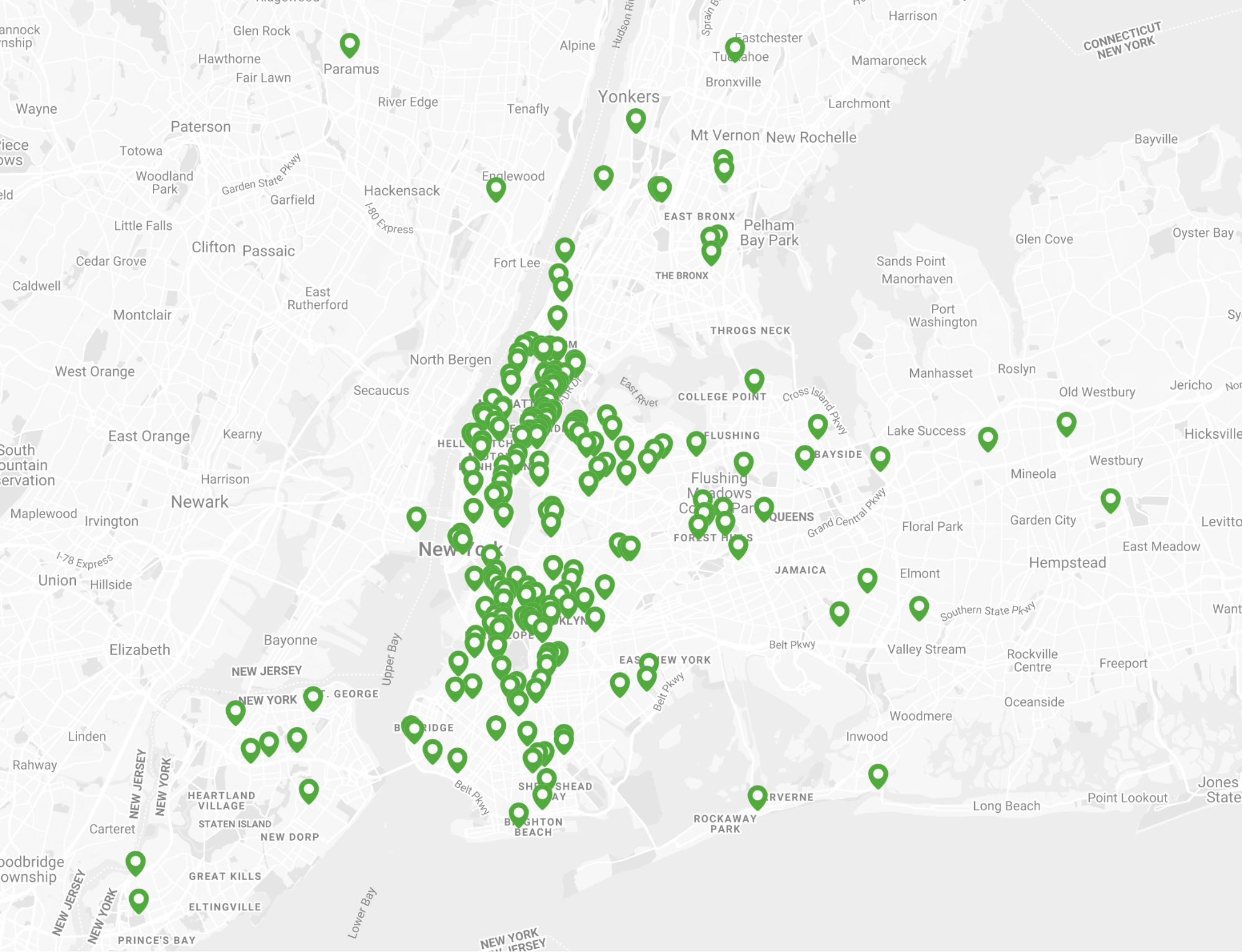

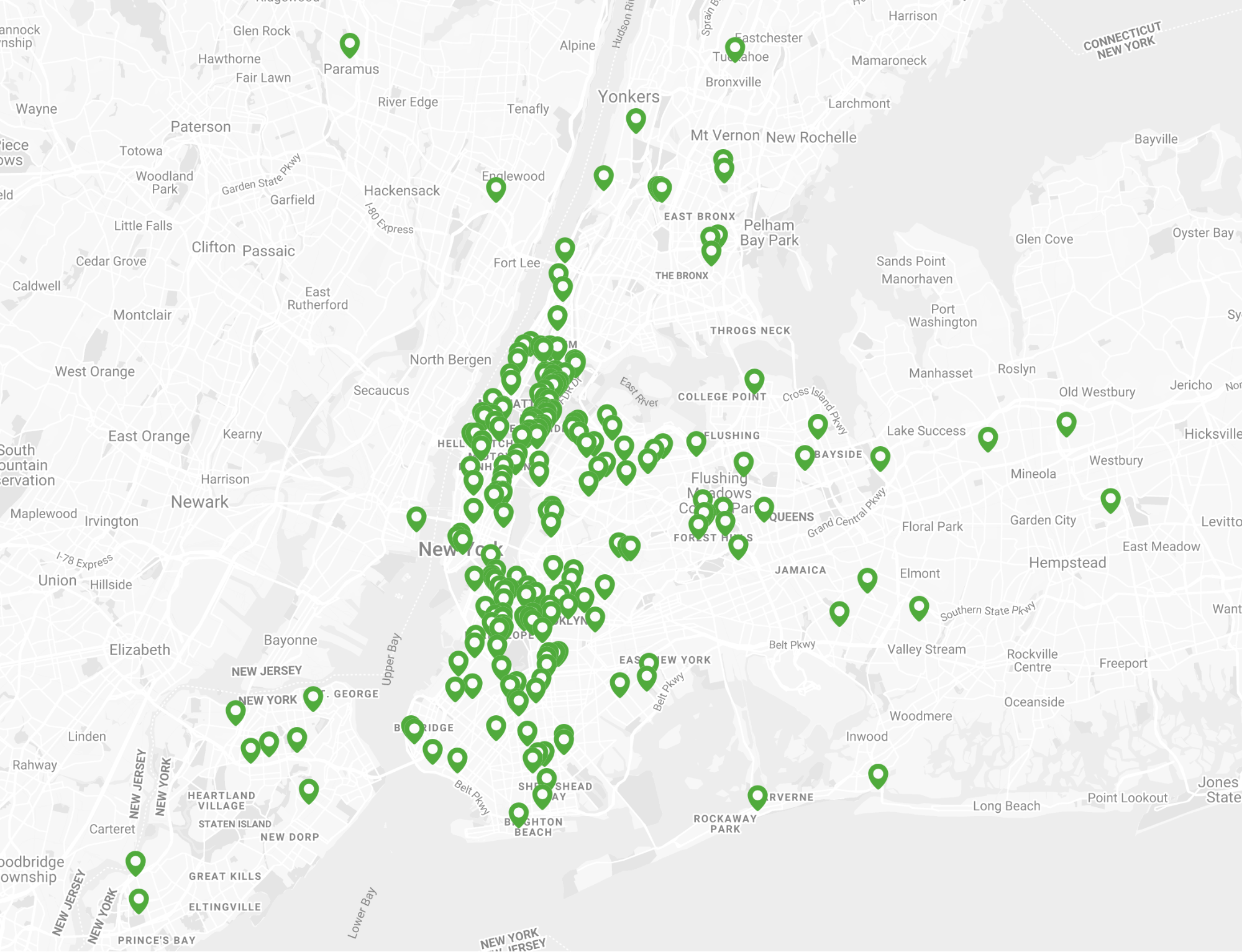

Locations of completed micro-batch deliveries as of April 10, 2020 (image credit: Xin Liu)

In the past few days, both #NYCPPE and N95forNYC have received press requests. Most of them are looking to highlight the fund-raising and donation efforts of Chinese and Chinese-American communities, in the face of the growing racist and anti-Chinese sentiment. I have mixed feelings being celebrated and villainized at the same time, where actually, I’d prefer neither. I couldn’t agree more with Camus as he wrote in Plague, “This whole thing is not about heroism. It’s about decency. It may seem a ridiculous idea, but the only way to fight the plague is with decency.” Looking back, when I was recovering from my fever and feeling down stuck at home. I lost interest in anything. My work was stopped and life felt stagnant. The tedious volunteer work punctuated by "thank you" messages from health workers made me feel needed again. Couriers came to pick up supplies at our apartment starting at 10:00am every day, which forced me to get up and maintain a routine. Volunteering slowly brought me back to working and reading. I felt better. Last week, Gershon and I drove to Staten Island for several deliveries. There was no traffic and we ate lunch in the park. If we had gone on the trip for fun, we would have felt guilty. But since it was for PPE deliveries, we felt at ease. We were able to enjoy the time outside, the scenery along the way.

Starting in mid-March, I became a COVID-19 “expert." Friends and family would turn to me, asking about the difference between social distancing and quarantine, whether and how to wear masks, how to sanitize the phone, keys, clothes, etc. All my "expertise" comes from having read the news from China since the outbreak in Wuhan. The same went for me and my Chinese friends’ immediate response to the PPE shortage, as we’d all seen the same plot play out 3 months earlier. We knew what would happen, what would be needed: first, the respirator masks, then medical coveralls, then ventilators, then makeshift hospitals. It felt like we were living in a sci-fi movie, not in the way Žižek fantasized about Wuhan, but one in which some people know the “future”, so they can plan ahead and act fast. When I voiced the need to cancel SXSW back in early March, my non-Asian friends and colleagues did not agree with me. Most of the arguments against cancellation focused on the economic consequences, but there was a constant undertone to it all, as if COVID-19 wouldn’t be the same in the US, really. When lessons from the infamous Biogen conference in Boston and New Orleans' Mardi Gras have proved my prediction, I felt validated but at the same time rejected and invisible. My peers couldn’t accept the severity of the disease, the imminent self-quarantines and closures. But why was it so difficult to face a pandemic that had already taken place for months? It was painful for me to confront that the racial bias is so rooted in our minds, that could render an infectious disease “Asian”. The 45 days lived by the entire Chinese population inside their homes were passed off as distant foreign authoritarianism and results of “dirty” Chinese eating habits, not something accepted in the western timeline. The few ones who relate to these shared experiences ironically ended up becoming “experts”, and here we are, living through the pain once again.

As China slowly relaxes its restrictions, I am seeing many pictures of people enjoying the springtime back home. The images are very similar to the ones taken by our PPE couriers out on their deliveries. Springtime cherry blossoms blur these two worlds for me. Now, in #NYCPPE conference calls, we talk about how our emergency rapid-response volunteer work might need to continue for 6 months, not the 2 weeks we initially planned for. Our team is building infrastructure and databases for the long run. As the head of the Brooklyn “warehouse," I have met most of our couriers from a safe distance. Although everyone wears a mask, I’ve started to recognize them from their postures and voices. Last night, I joked in the group chat that we’re like a delivery startup now with all the efficiency and usual divisions of labor, only we’re all hoping these jobs won’t need to exist sooner rather than later. When that day comes, maybe we can finally grab a drink all together, momentarily unmasked.