This text accompanies the presentation of Art Thoughtz as part of the online exhibition Net Art Anthology.

Michael Connor: Can you tell me about what led up to Art Thoughtz? What were you doing before you came up with Hennessy Youngman?

Jayson Musson: I started graduate school in 2009. It was about eight to nine years in between undergrad and graduate school. I still made art in between those times, and I made music. Going back into the school setting was somewhat of a culture shock.

Philly, it’s kind of a debaucherous, free-form kind of world, and academic fine art is just the total opposite of that. For me, school was quite an alien culture.

MC: Before going back to school, were you involved in the Philly art scene, like Space 1026?

JM: Yeah. I had a studio at 1026 twice, in 2002 and then again in 2006. There are many, many artists in Philly. The art world in New York is vastly different than the art world in Philadelphia, because so much capital and media is centered in New York, and it doesn’t necessarily look outside of itself, except maybe if it’s looking at like Los Angeles, or Berlin or London. Philadelphia is very overlooked, and in some ways it’s good, some ways it’s bad.

It allows the city to develop its own innate cultural markers and values, and Philadelphia kind of resists being homogenized by trends in contemporary art.

I didn’t make art with the idea that it would A, be exhibited in large spaces, or B, make any money. I did text-based posters. I did a lot of cartoons, political satire. I definitely was more playful in my younger days, and I think that’s really important.

If I was in my late teens, early twenties, going to school in New York, and being in proximity to all these great institutions, it would have steered my art-making towards being enveloped in those institutions, where in Philly, I was just like, “That’s not an option ever at all. That’s like, something else, so I’m gonna fucking make these stupid cartoons, and do my like, vitriolic text-based posters. The Philadelphia Museum is not gonna show these, that’s not on the table. Museums, that’s just not for me.”

MC: Were you involved in an online art scene at this point?

JM: No. I think I had a website. I wasn’t aware that were people using [the internet] as a platform in and of itself, which is fucking rad, but I was a colloquial traditionalist with my brick-and-mortar drawings and writings.

MC: So how did Art Thoughtz begin?

JM: I think around my first semester [of grad school] I came up with the idea—in 2009—for the character, but I kind of sat on it. Essentially, I wanted to create a stand-up comedian who talked about fine art, but in a comedy setting. Hennessy Youngman was conceptualized as a comedian, like a lesser-known comedian from the Def Comedy Jam era of the early ’90s.

The first video I filmed (in the bar I was working at, at the time) was modeled after a stand-up set. It’s called Hennessy Youngman! Live at the Laughway House! I enjoyed it, but when you kind of create this mock setting for a comedy club, it becomes more about how you fabricate the environment and simulate the stand-up set.

I did a second video, which was just a talking head video, which is me taking my same notes and doing it in monologue format to the webcam, and that felt better to me. The focus was on the words, the dialog, not on like, “is this a real comedy club?”

Initially it was wanting to discuss a quote/unquote refined fine arts culture, but in this garrulous kind of way. The kind of cultural opposition at play. This person who seemingly didn’t have, at first glance, the position to discuss these things with any authority.

MC: Did you actually perform the character in comedy clubs?

JM: No. I’ve never done a live comedy set in my entire life.

MC: Was it always the intention to put the videos on YouTube?

JM: Nah, not at all. I initially made them as video art. They were actually initially conceptualized to just be shown in a gallery setting or an exhibition setting, whatever that might be. Even though I was addressing the internet, saying “what’s up internet?”, that was just a part of the performance. It wasn’t until I showed them for review in grad school that I decided to put them online.

MC: Do you remember what was the impetus for doing that?

JM: It just seemed like a waste to keep the videos in the context of an exhibition. Exhibitions just don’t happen frequently, and I felt that it’d be interesting to give the videos a chance to live in a more dynamic context.

MC: When you began to upload them, can you talk about the initial reception? Who were the first people to find out about the videos, and when did you notice they were starting to become popular?

JM: Initially, the viewership was people and friends from Philadelphia, and those friends adjacent to them who might share friend networks and social media. The viewership was really, really small, actually, maybe a couple hundred views for each one of them.

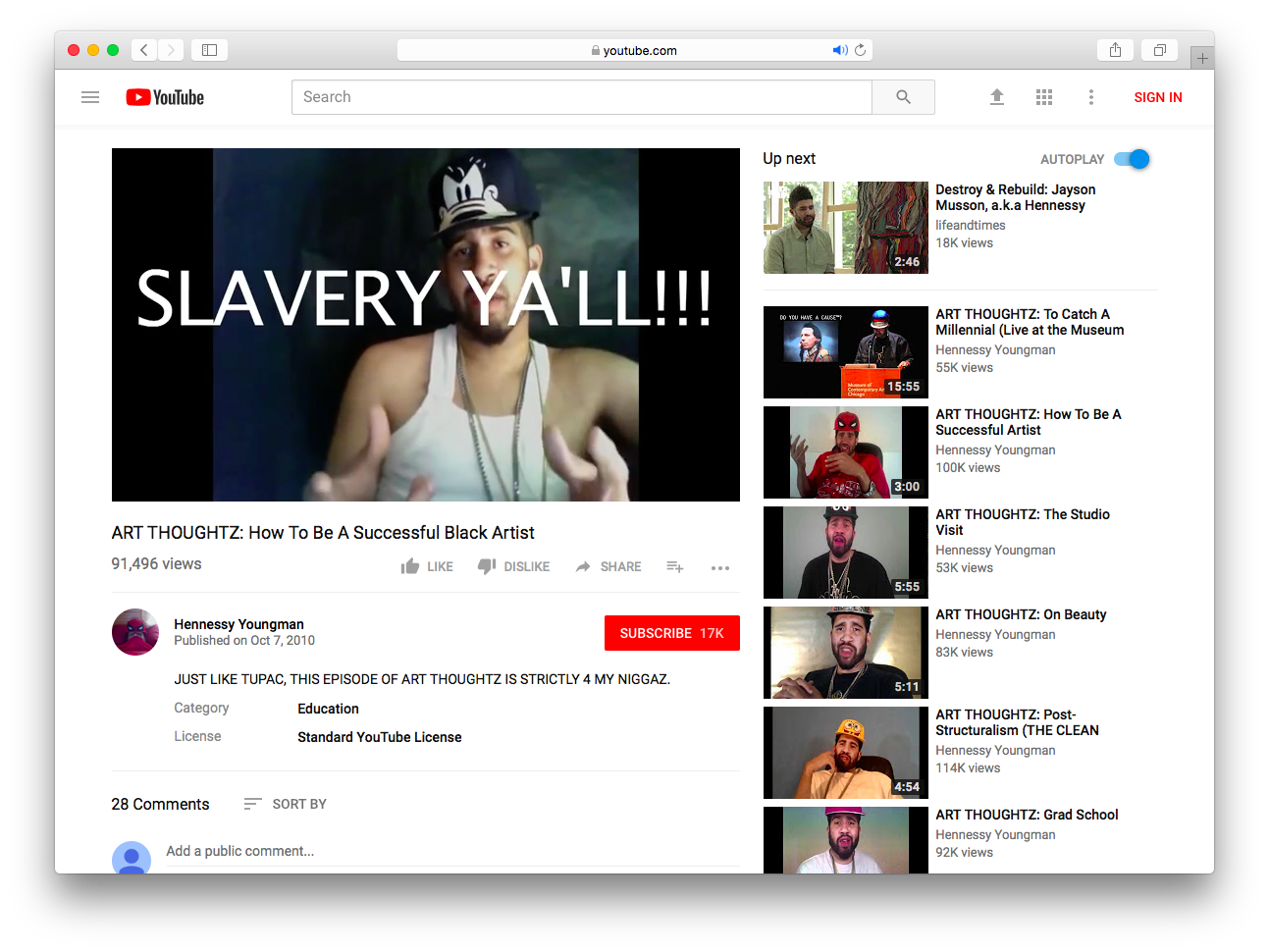

Then I did the Post-Structuralism video at the end of 2009, maybe. That was somehow picked up by Art Fag City (now ArtFCity). But they shared that, and then that was shared more widely within the art world at large, the New York art world, I guess. Then that kind of began the mass sharing of those videos in the larger art world. [That video] was taken down from YouTube for the fucking scene from The Crying Game–which I originally pulled from YouTube. I think someone just reported it, because why not?

I kind of lived in a weird Philadelphia bubble, and I wasn’t an avid reader of those blogs. Honestly, when I started that project, I didn't think anyone would watch the Hennessy Youngman videos. I was looking at other video art pieces that had somehow ended up on YouTube, and the viewership numbers were pretty low.

I didn’t really expect people to watch them, but I did want the videos to have some kind of public life.

MC: Did you notice your online audience shift away from art at some point, or cross over to a wider public?

JM: I did notice. I don’t really know when, but the videos did end up receiving viewers outside of art, that I guess enjoyed them for the humor.

The opening of Itsa Small, Small World at Family Business in 2012

MC: You had an opportunity to meet your online public when you did the open call project in 2012. What did it feel like to meet those people that had connected with that character you created?

JM: Kind of insane, man. That project, Itsa Small, Small World, I knew that I was gonna be stopping the project, and so I guess for me, that project, the open exhibition was kind of like a goodbye and thank you in a way. I didn’t make an official farewell, but I wanted to do something that could have some kind of physical catalyst to bring people together. But, I also was just curious to see what, who, the online audience, what this audience kind of looked like, and what do they look like coalescing through a space.

It was an interesting experience, partly because I didn’t really know what it would be. The opening wasn’t anything that I expected. We were already jam-packed. People were still bringing work in. People were just dropping their work off after the exhibition opened. People turned the opening into their own performance space. People took it into their own arms, and I really, really enjoyed that, because I have this static idea of an exhibition. Then to have different people turn it into their own venue in their own ways, it was awesome to me. It absolutely defied the narrow scope of what I had initially intended it to be.

People just kept dropping their work off. It was like 550 official submissions in that tiny space.

MC: Oh, wow.

JM: Then we took the unclaimed works and just distributed them on the street after the show closed.

I didn’t really give it that much thought, that that would be an opportunity for people who haven’t really had a chance to exhibit, to show their work. I don’t know why. I think YouTube had rotted my mind into thinking that everyone has a chance to get their voice heard, put it online.

There are a lot of people in New York, or just in general within the art-making world, that really don’t ever receive any kind of platform or audience, or have a venue to share their work with anyone. For a lot of people, I think that exhibition was a minute chance for them to present their work to the world, present themselves to the world.

That was a really endearing experience, ultimately, and I re-evaluated my own luck in having a project that received any kind of attention at all.

Installation view, Itsa Small, Small World (2012). Courtesy of Jayson Musson.