If the World Wide Web is an iceberg, its tip is the Surface Web, the Visible Web, the Indexed Web, the Lightnet of detectable cyberspace. This is the 4% through which average internet users navigate each day, while the remaining 96% rests beneath a veneer of public search engines and social media. This vastly uncharted alternate multiverse is colloquially termed The Deep Web. Yet even further within such recesses, lies a Dark Web—through which the Silk Roads of the e-scape wind over, past, and beyond servers, where cryptomarkets offer goods to buyers without the utility of exports, imports, and governments in general—undulating and virtually untraceable. Whereas these darknet zones originally served to sell anything from illicit drugs, pornography, and weapons, to prosaic merchandise, the digital marketplace today has evolved into an arena of legitimized transactions and investments out in the open, involving digital currencies (also known as cryptocurrencies) such as Bitcoin.

Meanwhile, though online art networks have been in existence for quite some time, the art world has often lagged a step behind the breakneck developments of the tech industry. But over the past several years, in what could be considered a “digital media art” vogue, the exhibitions, galleries, and collections of today, such as Dot Dash 3, Vngravity, Daata Editions, and Sedition, have increasingly moved—sometimes entirely—into virtual marketplaces. For better and worse, the fate of these initiatives will be taken as an indication of the answer to a long-standing question: can art display and collection be sustained in the screen-contained expanse of game engines, AR, unsupported plugins, mobile apps, defunct links, and the swelling necropolis of extinct sites?

_by_harm_van_den_dorpel%2C_2016.jpg)

Harm van den Dorpel, Autobreeder (lite), 2016

Left gallery, based out of Berlin, is a particularly enterprising model, the first to directly employ Bitcoin and blockchain technology, though it does not (yet) operate on the Dark Web. Co-founded in 2015 by artist and programmer Harm van den Dorpel with anthropologist and partner Paloma Rodríguez Carrington, it is perhaps the most organic offering within this space, given its adaptation of cryptographic exchange and computational language. Supported by cleancut content, sleek aesthetic form, and the mission to “produce and sell downloadable objects,” the platform’s matter-of-fact UI—designed in collaboration with Beautiful Company—mimics the feel of an app store that meets contemporary art gallery. All available works and curated exhibitions are viewable via the click of a button and horizontal scroll. Said “downloadable objects” are available for purchase by credit card, PayPal, and Bitcoin in file formats such as, but not limited to, .epub, .mobi, .app, .exe, .saver, .mp4, .html, .gif, .txt, .rtf, and .m3u.

During his studies in artificial intelligence at the Vrije Universiteit and then in time-based arts at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam, van den Dorpel first noticed the art world’s lack of affinity for and indifference towards the curation and preservation of immaterial media. After he attended an event at the Austrian Museum of Applied and Contemporary Arts (MAK) in Vienna in 2015, by invitation from Cointemporary, left gallery was born. The museum bought one of van den Dorpel’s works, Event Listeners, which became the first recorded occasion that an artwork was purchased by an institution using Bitcoin, and eventually all one hundred editions of the work sold out. With the hope to fill a gap while extending the precedents set by platforms such as Cointemporary, van den Dorpel and Rodríguez Carrington geared left gallery’s vision toward a generation acclimated to buying smartphone apps, icon packs, and subscriptions to software and streaming services.

This model, centered around “affordability,” translates into a collection of large editions (often in editions of one hundred) made accessible to a wider demographic of collectors, while simultaneously made scarce on the web in order to sell exclusive, largely commissioned work. So far, the gallery’s growing collectorship includes a wide sample set, from graphic designers to startup offices, individual collectors from the tech and business worlds, to speculation-focused art collectors in China purchasing with Bitcoin.

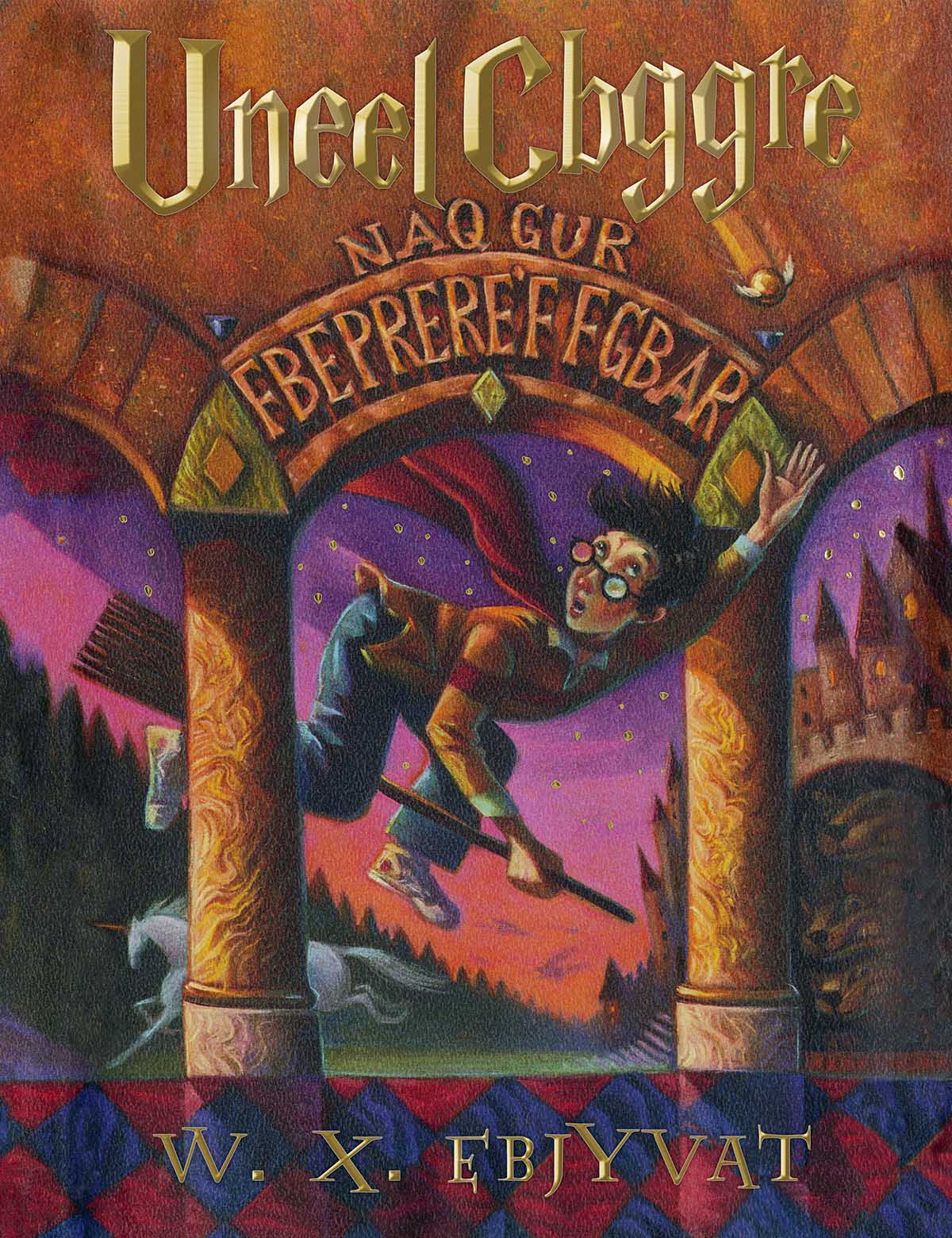

Damon Zucconi, uneel cbggre naq gur fbeprere'f fgbar, 2016

A quick primer here for those unfamiliar with the lingo: cryptocurrency is an electronic currency type for the online market, and Bitcoin is the earliest and most popular decentralized cryptocurrency. Underlying Bitcoin and many other cryptocurrencies is the technology of blockchain, which helps create and then serve an open consensus of synchronized data that records transactions between two parties efficiently, in a verifiable and permanent way. By design, blockchains are immutable to any data modification without the consensus of a majority of users. Bitcoin is just one of many possible applications of this particular blockchain, and there are many other customized blockchains, each with many possible applications built on top of them.

In an application of ingenuity, left gallery’s platform further authenticates its editions through a platform called ascribe, which facilitates the connection between art world makers and collectors and auctioneers. The platform further registers all works, offering artists a way of selling with a certificate of authenticity attached to the moment of timestamping ownership. Any information can be stored in the blockchain. If ascribe or left gallery cease to exist, that information will remain verifiable as long as the blockchain is around, since ascribe only offers the interface which places the work on the blockchain. Through a seemingly complex technical story, ascribe reveals itself to be quite a basic service. Once collectors understand how their ownership is stored independently, the purchase incentive increases. Perhaps most credibly, ascribe’s system allows the resale of editions independent of the gallery’s interface, as opposed to other digital edition sites that vendor-lock work into their platforms. Left gallery therefore makes it possible for collectors and buyers to take that artwork out of its original context for recirculation in the wider art market.

William Kherbek, Retrodiction, 2017

In a vignette published in Spike Magazine, the gallery’s curatorial vision explores “the quasi-colonial relations that are increasingly being built into the internet’s infrastructure, a mentality left gallery seeks to confront and oppose.” The mobile landscape has undoubtedly been dominated by heavy corporate censorship. The only way to get an app on a smartphone is through an account with Google or Apple which earns 20% of the revenue from purchases. And for every app purchase from any kind of service or shop, there is a further sum deducted just to allow the transaction to take place. Left gallery offers a way of bypassing this system by offering apps otherwise disallowed by Apple or Google (given that there are no categories for “art” in those app stores).

The question of obsolescence is a pressing one. “Digital editions” of works shown by galleries are often limited to video, and do not necessarily take full advantage of the new medium-specific capabilities that software offers. Even software and files are now becoming outdated with the advent of online streaming media. Packaging the works as standalone “files” simplifies some of the issues inherent in browser- and network-dependent works. Left gallery takes a pragmatic stance towards conservation issues, exploring a range of strategies depending on the artist’s project alongside practical considerations. For instance, when macOS does not support a particular screensaver file format anymore, the software will be recompiled in collaboration with the artist.

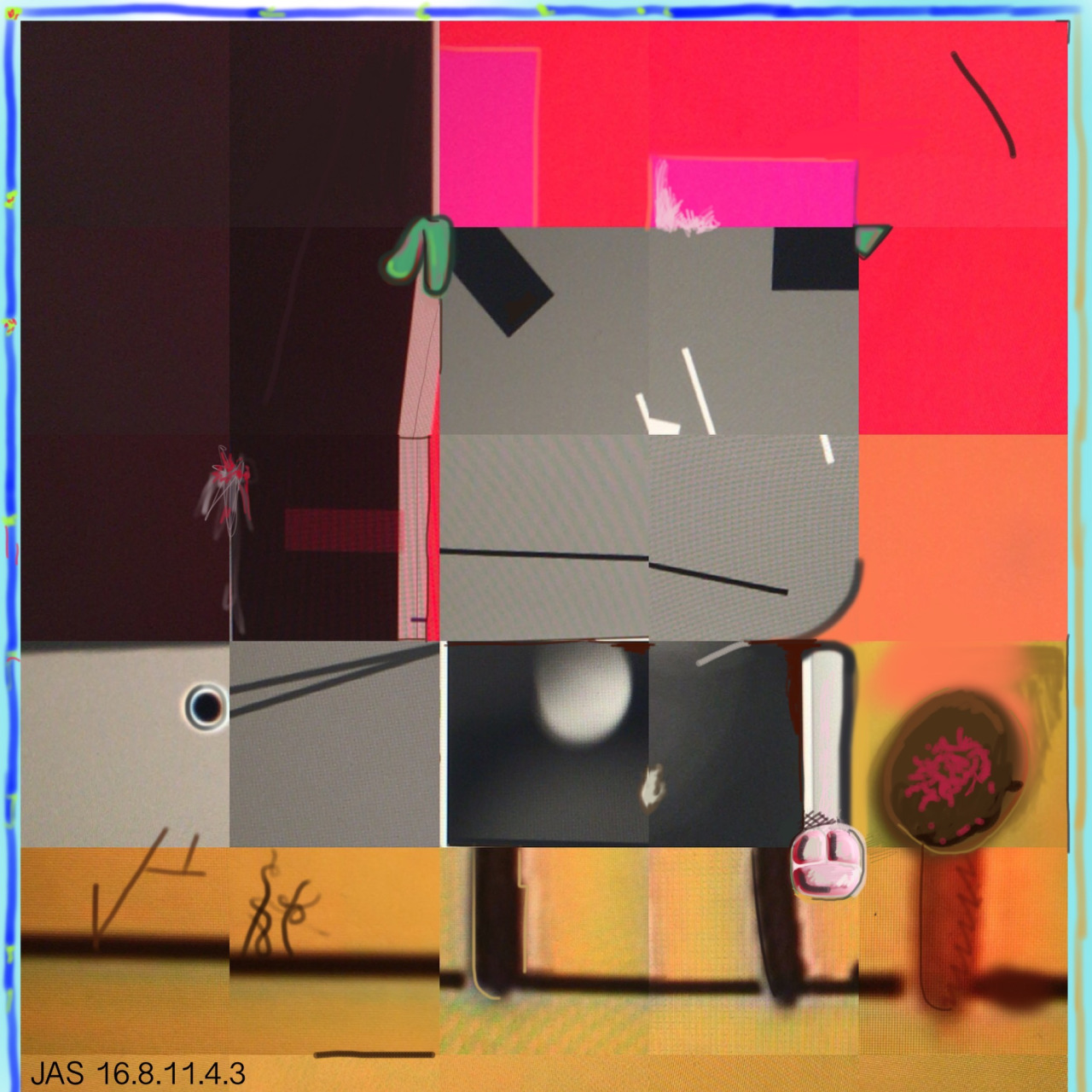

Jeffrey A. Scudder, JAS 16.8.11.4.3, 2016

In a conversation over Skype, van den Dorpel muses, “left gallery offers software so that the art can be interactive and generative. Not only using decentralized technology for ownership but also for payment, and calling it left gallery, is a political conviction. We have very limited means of opposition or rebellion, but generally, art has a very small but direct force.”

As Rodríguez Carrington elaborates, “The most important thing is that we offer art, and that people can buy this art without understanding blockchain or Bitcoin. We don’t perceive these works as purely digital or virtual; they are actual objects, hence ‘downloadable objects.’ The blockchain enables us to offer people a decent and relaxed way of ownership, of collecting art, while supporting the artists directly.”

Rodríguez Carrington’s background in anthropology with a concentration in popular culture has further driven left gallery’s broader interest in the art world as interdisciplinary community. The gallery hosts events in physical spaces, its owners understanding that an exponential increase in online peers has not diminished—and perhaps has only exacerbated—a longing for physical contact. Offline events have incorporated digital painting, live performance, music, and cooking as a way of increasing visibility, introducing artists and the gallery to the public, and expanding dialogue. In one collaboration with the artist William Kherbek, the gallery worked with a bookstore in Amsterdam selling physical copies of the artist’s poetry, and organized a poetry reading in conjunction with the launch of their virtual poetry pieces. Other collaborating artists include Micah Hesse, Dorine van Meel, Damon Zucconi, Gene McHugh, Sean Lockwood, and Ryan Kuo.

.jpg)

Gene McHugh, Bang Bros, 2015

It may be interesting to note that despite the exclusivity and legitimacy which comes with physical gallery space (versus the lack of scarcity in cyberspace), software-based works that are inserted into actual physical spaces take on a newfound scarcity via a subsequent need for programming. This demand adds value and legitimacy to the software-based artwork, bringing value full circle. Perhaps one recurring lesson is that founding utopian ideas driving the development of the internet and the internet art lauded in the 1990s do not and cannot survive on their own, without adaptations of hybridity, and hybrid exchanges between on- and off-line, as left gallery practices deliberately.

In terms of expanding a long-term vision, left gallery has also begun to offer “mastery editions”—unique, extended, and exclusive editions which are further bound to hardware—equipped for those collectors looking for guidance in terms of display, an output the gallery describes as more “backroom” and off-model. While there aren’t necessarily plans to start sending out small computers or screens to individual buyers, left gallery does aspire to find solutions for digital art collection in real time. “We’re not looking to get the next thousand digital artists to use our platform. The curatorial process here is very important and we include works that we believe in,” van den Dorpel affirms in conclusion. “We’re not a startup in the capitalistic sense, which is very much based on quick growth, quantity in user-base, investors, and exit strategies. I think it’s most critical that left gallery as a whole has an experimental and collaborative structure. The future is to maintain what we do, while making what we do clearer and clearer. We’re not in a rush.”

While the value of the few million existing bitcoin across the globe is on a parabolic rise, with a predicted end-game value of $400,000 each, according to analyst Ronnie Moas, left gallery hopes to meet the increasing demand for digital artwork by offering an organic solution to the precarious complications of virtual art circulation for both artists and collectors. While the blockchain-based space certainly operates on left-leaning attitudes regarding accessibility, the platform itself is one where the worlds of tech and art, software and hardware, virtual and actual, collide at a generative center.

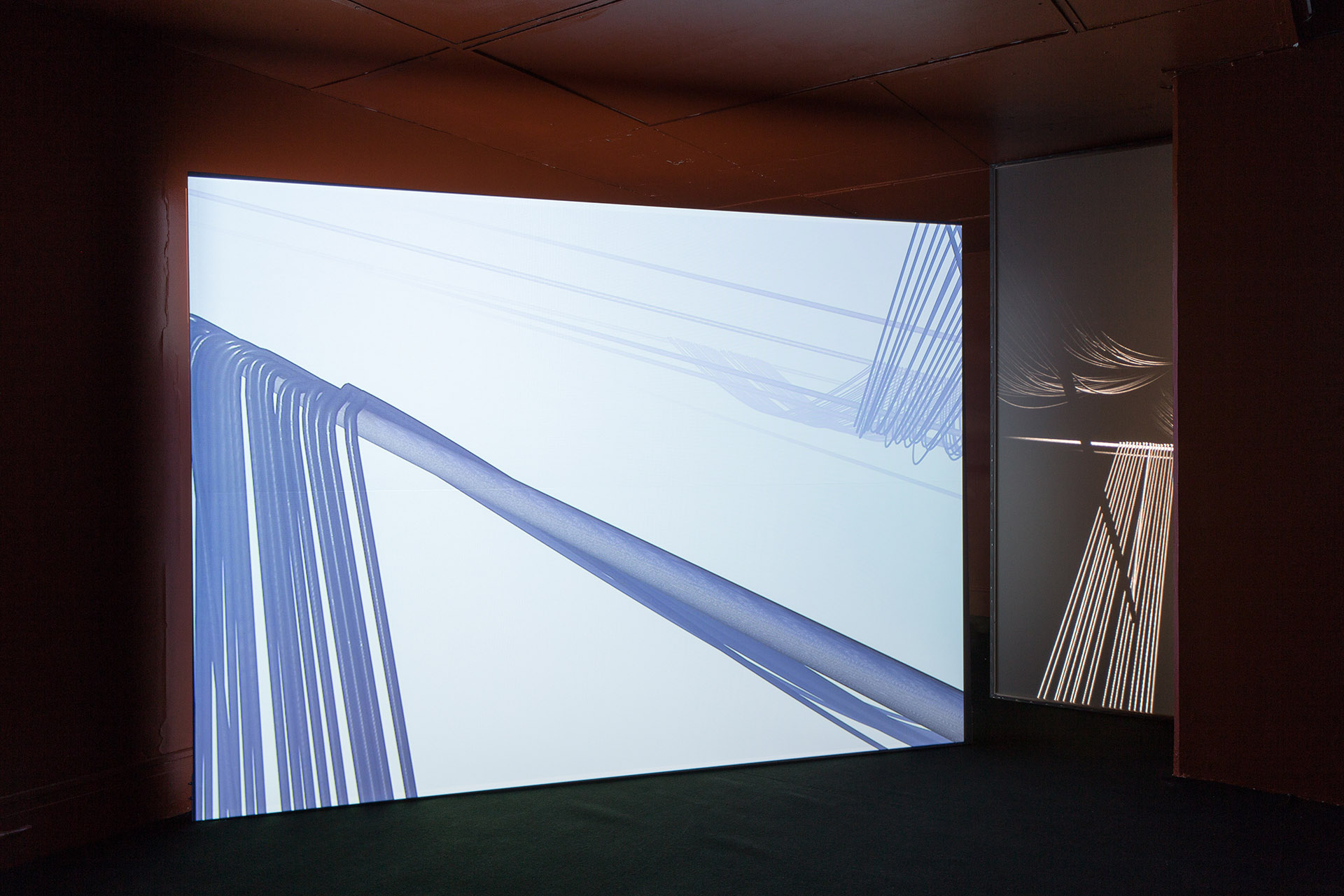

Header image: Dorine van Meel, Disobedient Children, 2016