Image: Miao Ying, LAN Love Poem—FLOWERS ALL FALLEN, BIRDS FAR GONE (Still), 2015. GIF animation.

This article accompanies the inclusion of Miao Ying's Blind Spot (2007) in the online exhibition Net Art Anthology.

I landed in China almost five years ago, beginning a trip to Myanmar by bus and train that has not yet ended. I wanted to better understand how media, especially art, changes within different cultural, legal, and economic locales. I was just beginning to feel the dimensions of my lived experience in the US, the windows through which I saw the world, and wanted to push myself beyond.

Early on, I interviewed artist Miao Ying in a hip cafe in Beijing. Despite having no Google maps to help me find my way, and difficulties adjusting to censorship via VPNs for my Gmail, waiting for Miao I found myself closer to home than I expected. I ordered an Americano in English, and looking around, found half of the customers were on Facebook (over a VPN, of course). Down the street was a bustling McDonald’s. That feeling, of being at home, was a profound misreading of the place, and Miao quickly showed me just how far away I was from an internet and media ecology I understood.

Miao’s artworks, featuring remixes and collisions between various local internet cultures, were the most bizarre yet nuanced representations of the kind of cultural exchanges going on in China that I had yet seen. US media discourse presents China’s internet as a black box, filled with single-party promoted content and hounded by censorship and surveillance. I was led to believe that in China, there is no freedom, no opportunity for expression or cultural exchange. This was the West’s own propaganda, more subtle for sure, but there.

Miao’s animated in-browser collages of net screengrabs acknowledge these negative attributes, while also revealing insanely vibrant and weird net cultures thriving in spite of the limitations. Chinese netizens were picking from many influences locally, as well as around the world, and then remixing and transforming content. They created sophisticated and constantly mutating vernacular languages, at times in spite of censors, at times designed to escape the notice of censors. Google was simultaneously there, and wasn’t; privacy software allowed access, but the difficulty allowed for Chinese equivalents, most notably Baidu, to emerge and thrive. The tension produced a lot creativity.

Now, I live in Cambodia. Google hasn’t really fully arrived here. My street is not imaged on Google Street View (GSV). As I wrote for Rhizome in 2015, here, “a mere 26.7% of the population claims they've used the internet,” and almost exclusively through a phone. In Cambodia, poverty engenders lack of access to education and the requisite language needed to engage with technology. Of the small percentage of people online, they are predominately male, educated, relatively wealthy, and urban.

Growing up how I did, in a middle-class, white home on a pre-GSV grid, privileges of my offline world carried over as my life became more networked. I could connect and engage with people and ideas over great distances, while never experiencing censorship or harassment. Accordingly, it was easy to consider these corporate platforms as liberatory tools for exchange and self-expression. While Miao’s artwork showed the fallacy of an universal internet culture by highlighting the creativity on various Chinese platforms, Miao also helped me to reflect more critically on the parameters of my own networked life.

Miao’s work allows for a more nuanced view, one which creates space for agency. While networked power is undeniably undemocratically wielded in China and Cambodia, it too is increasingly centralized amongst a handful of private platforms in the USA. Companies such as Google possess an ever more powerful stake in how we see and relate to the world, yet meaningful access to their inner workings, their own black boxes, remains nearly impossible. At their most perilous, a corporation—like a government—that controls the means for relating to or seeing the earth risks reorganizing the planet to fit its business model. What artists can help us see inside our own centralizing internet? Who will show us Google?

What we see when we look at Google is a methodically manicured image. It is only advertising; noise hiding much deeper machinations. To begin with the basics and look beyond the sleek design and the various end-user interfaces Google provides, let’s reflect first on the hardware supporting our browser experiences. To do so, I turn to writer and artist Ingrid Burrington. Burrington investigates the politics embedded in networks, especially through their infrastructures, the hidden interfaces not for intended for us—the end-users—at all. Any ability I could claim to seeing Google, comes in part from thinking with Burrington’s writing.

In Burrington’s series of essays for The Atlantic, she seeks to counter what she refers to as the “pernicious metaphor of The Cloud.” What Burrington unearths are a much more lively, and untidy images. Through Burrington’s research trips, she begins to reveal for us some of the actual wires, data centers, and people constituting and maintaining a network. The hardware and people she finds therein are antithetical to the advertising we are sold; they are messy, fragile, and they are human. Their intricacies are often hidden within giant private data centers, or buried under public streets, only suggested at through obscure symbols spray painted on the sidewalks above.

We are encouraged by companies like Google to put as much of ourselves onto the network, to rely upon it completely. To entrust these platforms with precious family photographs, intimate correspondence, and our businesses, to name a few, requires a great deal of trust on the part of us, the end users. The more we come to rely on these services, and the infrastructure supporting them, the more trusting we must be.

To garner this level of confidence, the platform must present itself as seamless, the storage impermeable, and the connection flawless. This ephemeral, sleek, universal network is not at all what she uncovers. As Burrington writes, the “rhetorical promise of The Cloud is as fragile as the strands of fiber-optic cable upon which its physical infrastructure rests.” It doesn’t inspire a lot of trust, but this is how it all actually works.

But I didn’t know all that when I moved from my home state of Indiana to New York City in 2010. The myth and magic platforms peddled still felt largely real to me then. However, one of the first, personally monumental exhibitions I saw there was New Museum’s “Free,” curated by Lauren Cornell. “Free” featured work that deeply challenged not only my understanding of art, but also my assumptions around the kind of media ecology in which we were all swimming.

Wandering “Free,” I kept returning to works from Jon Rafman’s series Nine Eyes of Google Street View (2008 - ongoing). Rafman screen-grabbed, enlarged, printed, and framed an assembly of unrelated moments from GSV. Men in tracksuits flip off the camera; possibly sex workers stand along the road. A curious bright glitch stains an otherwise remote wooded road. I was previously aware of the project, but only via its blog. Physically manifested in the museum, the photographs gained a presence hard for most photographs, random or curated, to earn bumping around online. They demanded deeper reflection.

As writer Joanne McNeil noted in her catalog essay, the images possessed a disconcerting grainy quality, giving them a worn-out look that was discordant to the fairly contemporary tools (automated facial blurring) and prodigious scale of the project. While in-browser GSV’s images are utilitarian and impressively thorough, presented as finite art objects the tiny imperfections in the shots come to the fore.

These blemishes reminds us of Clement Valla’s essay and artwork, “Universal Texture,” which specifically seek out the imperfections in Google’s algorithms. Universal Texture is the algorithmic system that the company uses to create some of the most comprehensive—and certainly most used—maps of the Earth. Valla calls into question Google’s “God’s eye view” by slowly picking at the edges, searching for seams and cracks. While Burrington was busy digging for pipes and humming data centers, Valla begins at the opposite side by reverse engineering what Google shows us, in order to reveal the embedded politics steering our gaze.

Image via Clement Valla, 2012.

Image via Clement Valla, 2012.

Valla scours the Universal Texture, collecting what he calls “edge conditions”: instances that at first glance appear to be glitches, but in fact reveal glimpses into the inner workings of the map itself. Collapsed bridges or skyscrapers stitched together into near-cubist sculptures are the still-visible clues into how the algorithm attempts to stitch together a singular, universal view from millions of disparate photographs taken on different days, at various perspectives, altitudes, and with disparate technologies. These are the limitations of this still-human product.

In Rafman’s work however, the algorithm’s constraints are secondary to the unprecedented gaze GSV allows. For Rafman, GSV’s incursion into public space was a violent rupture in privacy. The blown-up shots simultaneously humanize and objectify the subjects, existing somewhere between fiction and a documentary. We pass and look at much as we drive and public space always contains passing glances, but in the moments Rafman has chosen, people are frozen in time, and a passing glance becomes a corporatized gawking.

“The detached gaze of the automated camera,” Rafman writes, “can lead to a sense that we are observed simultaneously by everyone and by no one.” Erasing these pedestrians’ identities through facial blurring, which Google does for legal reasons, is little absolution for the invasion. Whether we, the viewers of GSV, know who they are or not, whether we know exactly when these shots were taken, these people are captured, flattened, decontextualized, and made vulnerable in the unflattering utilitarian light of Google. Their image is not their own.

Jon Rafman, Nine Eyes of Google Street View, 2008–.

But Google is not a cohesive whole, either. GSV’s scale resists comprehension, but Rafman’s highly curated selection makes it possible. Google’s data—and therefore profits—come from a variety of quotidian sources, such as geodata from your phone or cookies from a search, the cameras on a GSV car, and frequently, an unseen woman, sitting for a long shift, scanning thousands of books, as is the subject of artist Andrew Norman Wilson’s ScanOps, (2012 - ongoing).

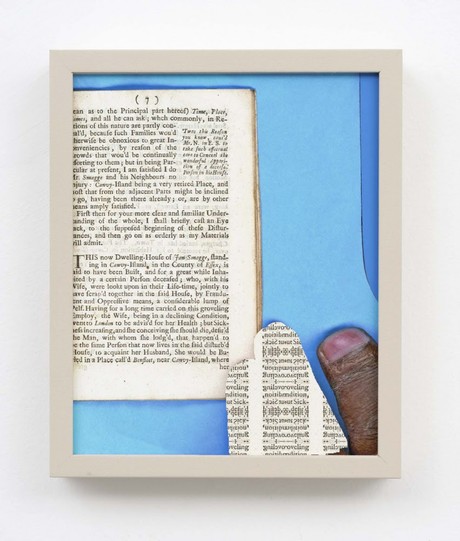

In ScanOps, Wilson collated small mistakes from Google Books scans such as the fingers of the scanners, or a page, only half-way turned and distorted. By collecting errors made by Google’s employees, Wilson highlights not the algorithms, but the labor, and most importantly, the employees behind the scanning. So as Rafman calls attention to and humanizes those captured by GSV, so does Wilson for some of the most marginalized employees within the Googleplex.

Looking through Wilson’s selection, we find odd glitches and lovely color schemes such as a white page, and pink rubber thimble worn a brown-skinned hand, accidentally captured. Slowly, the number of digits of people of color in ScanOps becomes unignorable. When Wilson—noticing a racialized difference in labor—attempted to interview and film these workers, he was promptly fired from his contract at Google. His footage was ordered to be destroyed. The resulting artwork, Workers Leaving the Googleplex (2011), details the story.

Andrew Norman Wilson, An Exact Narrative of Many Surprizing Matters of Fact Uncontestably Wrought By an Evil Spirit or Spirits, In the House of Master Jan Smagge - 8, 2012. Inkjet print on rag paper, painted frame, aluminium composite material.

Wilson highlights the distinct classes of workers within Google, and the proportions of privilege and respect they are allowed. While Silicon Valley promises high wages and respectable jobs, data entry remains nearly invisible, and decidedly so. Asking how the service is made, how it works, who profits from it and who doesn’t, stands to tarnish the company’s image. Luckily for Wilson, he was already planning on quitting for graduate school. I wonder whether any of the scanners would be so lucky.

These curated windows into Google begin to reveal the dimensions and power of its gaze. We see bystanders within their own personal stories, staring at the nine camera clad car, and we stare back at them. We are given access to data, but we cannot forget the people who made it possible. We may use this exceptionally large map, but here we are reminded of edge conditions left by imperfect technology and the programmers still troubleshooting. In the process we begin to feel hints of the dimensions of Google. It is a subtle, and pervasive presence, its mode of looking and collecting everything, embedded into our daily lives. But, what can we do?

There is a slow-creep to surveillance, always searching for increasingly granular data. Obfuscated collection and labor hinders awareness and agency, not to mention protest. As Rafman reflects, while there is a “‘report a concern’ on the bottom of every single image, how can I demonstrate my concern for humanity within Google’s street photography?” The space in which to have this discussion, the edges with which to see, for room to reflect, are barely visible now, and constantly shrinking.

In seeking to organize all the world’s information, Google has the potential to reorganize much of the planet to fit in with its bottom line. Searching behind the interfaces we so often take for granted in-browser, these artists reveal complex undercurrents, bubbling just beneath their smooth surfaces. They provide tangible artifacts and frameworks with which to see and debate Google’s own black boxes. They offer their concern.