This interview accompanies the presentation of Mendi + Keith Obadike’s Black Net.Art Actions as a part of the online exhibition Net Art Anthology.

Aria Dean: What prompted the Black Net.Art Actions project?

Mendi + Keith Obadike: We had been making projects online for a couple of years. Our site Blacknetart.com was inspired by a shop that Mendi’s parents (who are academics) had in the 1970s called Blackness Is . . . The shop was a place where you could buy art objects, crafts, and kitsch from Africa or African-America. We loved that the name of the shop was the beginning of a sentence but the end was open. It felt more like a question, and we thought of these actions as a series of questions about Blackness we wanted to pose on the internet.

We asked these questions against a backdrop of a scene were commercial ventures were selling the internet to the public with the notion that in the absence of mediating everything through our physical appearances, we would be free of both racism and race itself. There was already some push back on this notion coming from scholars in media studies and ethnic studies, but most artists working on the net seemed to be concerned with other issues altogether. For us, the various strategies at work in a conceptual art practice, our lived experiences as Black people, and the virtual terrain of the internet suggested a clear way to put pressure on these conversations, engage our communities, and invite others into our serious play.

AD: You work across many different mediums, but what drew you to use the internet as a way of exploring these questions of blackness and identity? What does the internet offer that installation and sound can't?

M+KO: We started working online because it was a way to play with images, text, sound, and time in a really flexible format. We liked that there could be multiple ways of entering a piece. We also enjoyed that challenge of dealing with contingent network access speed, screen color calibration, etc. The internet was also both a venue and an instrument at the same time. We began working online because we were living part of our lives online. We believed in making art everywhere.

AD: Today, online and on social media, blackness is hypervisible. Images of black people and black culture circulate rapidly and with great reach. There are elements of this that are new, but we also know that it’s an extension of existing cultural dynamics that long precede the consumer internet. Can you talk a little bit about what we might call “state of blackness” online at the millennium? How did you see blackness in relationship to the discourse around online identity at the time?

M+KO: There were always elements of Black culture online as well as the idea of Blackness. From the earliest days of the network, even when it was dominated by academic researchers and government employees, people were injecting ideas about gender, race, sexuality, and culture into the system. Perhaps even the need for a late-1960s robust communication network (Arpanet) rose out of concerns about the Civil Rights Movement and general social unrest in America. As we have pointed out in other places, in the ’90s the language of the internet was the language of western exploration colonialism, from Netscape Navigator, Internet Explorer, Ebay.com, Amazon.com. We started working online in 1996 and we were mainly talking to groups of artists, primarily media artists around the world. By the late 1990s/early 2000s, we had a critical mass of Black people online and artists participated in listserves like Alondra Nelson’s Afrofuturism group and sites developed like CafelosNegroes.com (a Black and Latino space) and later Benjamin Sun and Omar Wasow started Community Connect Inc., the parent company of BlackPlanet.com, AsianAvenue, and MiGente.com.com. All of these commercial and community projects affected how everyone online thought about race and culture. AD: Both Blackness for Sale and The Interaction of Coloreds deal with race as material or concept beyond its attachment to a given body. Blackness for Sale finds Keith auctioning off his “blackness,” seemingly questioning the ontological status of blackness at large, and drawing attention to blackness as a commodity. Blackness becomes transferrable. The Interaction of Coloreds also plays with the materiality and ontology of race, but looks more at the pseudo-objective regime of racial classification and colorism. Can you speak a bit about these two works and their relationship to each other?

AD: Both Blackness for Sale and The Interaction of Coloreds deal with race as material or concept beyond its attachment to a given body. Blackness for Sale finds Keith auctioning off his “blackness,” seemingly questioning the ontological status of blackness at large, and drawing attention to blackness as a commodity. Blackness becomes transferrable. The Interaction of Coloreds also plays with the materiality and ontology of race, but looks more at the pseudo-objective regime of racial classification and colorism. Can you speak a bit about these two works and their relationship to each other?

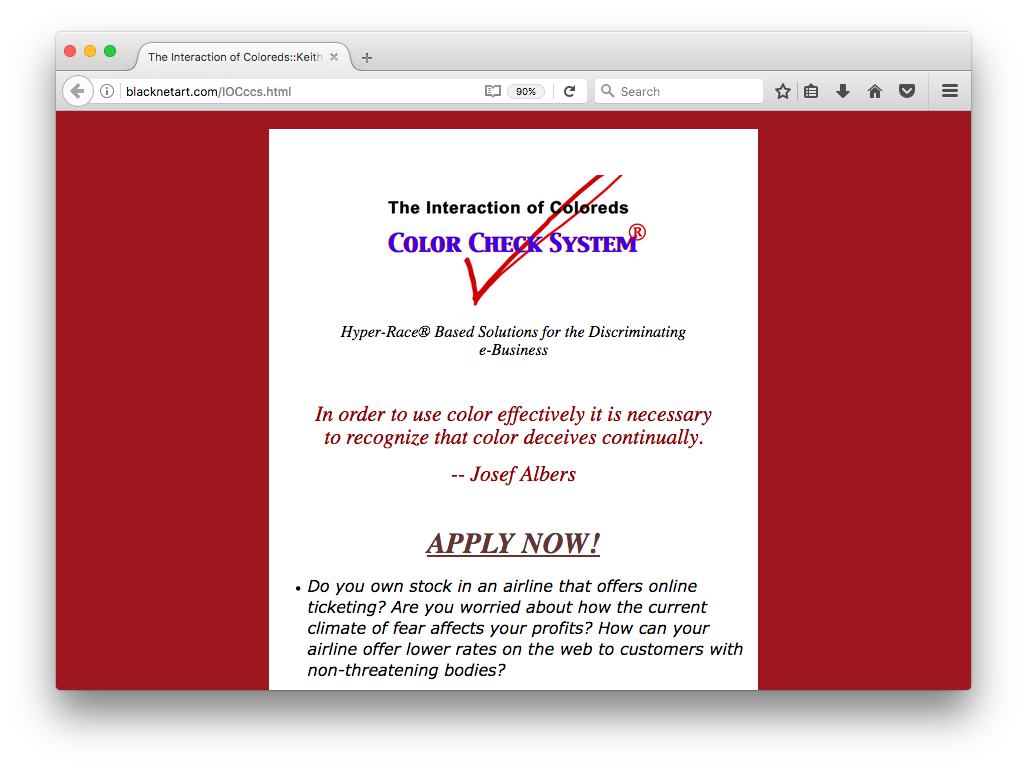

M+KO: The Interaction of Coloreds is about new mediated ways of “looking” and it plays with language of color theory. We use phrases from Albers’s The Interaction of Colors to hint at a kind of racial coding that we imagined might happen online. The project is an online brown paper bag test. We ask audiences to answer a question about color and relations and also to photograph parts of their body associated with color classification—behind the ears, fingernails, palms, faces, eyes, etc. In return, we offer to assign a hex code for that person’s skin color (so that it can be read accurately across browsers). We were playing with what we called “social filters,” or the mechanisms that allow or deny access based on social classification. It was one way of thinking through and pushing back on the claims that race didn’t matter online because we didn’t see people. We understood that we’re never just seeing people in real time. We’re also activating a series of calculations that are stabilized in our imaginations as color terms, but they are more dependent on interpretive frames and relations than on color. We continued this exploration of color in the final piece in the Black Net.Art Actions suite, The Pink of Stealth (2003), which was commissioned by the New York African Film Festival and Electronic Arts Intermix.

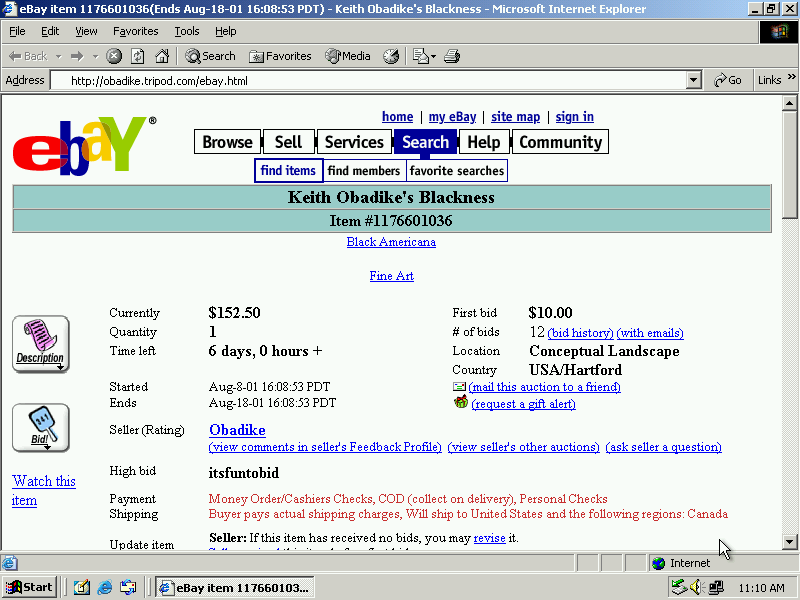

In Blackness for Sale, we offer Keith’s Blackness for auction at eBay. The piece suggests that with his Blackness, the buyer would acquire a series of benefits, but we also caution that it also comes with some concerns. Audiences are invited to laugh, read aloud, and share the text. They are also invited to assign monetary value to the blackness. Blackness for Sale plays with the idea of an online transferable identity. During the early days of the net there was a fantasy of going online and taking on a new identity. We wanted see what an artwork could say to this question of who are we when we are online and ask questions about where Blackness (race and culture) lives. Is it in the body or somewhere else?

Both projects ask questions about value, color, and/or race as code, and interpretive frames. They are both performances and they both invite audiences to perform.

AD: Both of these works also seem to be concerned with authenticity. The Interaction of Coloreds is really tongue in cheek about it, highlighting the absurdity of the intricacies of racial categorization. How can there be an authentic blackness when the boundaries are always shifting? Likewise Blackness for Sale pokes fun at its subject. In some ways, it seems like undermining authenticity is one of your goals. Would you say this is the case? What are your thoughts on authenticity as an ideal—particularly online?

M+KO: When we talked to each other we were primarily concerned with other concepts, like interpretation, relation, and value. Once you start down that road, however, of course authenticity comes into play. We would have said that we were asking questions about race, difference, nation, and belonging. We wanted to unearth some of the implications of the words we use to talk about these things. Some people were arguing that race had less meaning online; we felt, instead, that racial logics were accruing new methods of operating. We noted that in the online environment people use both language and images associated with race to assign value in the marketplace, and we wanted our work to invite meditation and dialogue about that.

AD: Blackness for Sale also opens up an interesting conversation about censorship. eBay removed the auction for Keith’s blackness from the site. To me, there is something interesting about seeing blackness policed online—here, not just in the sense of traditional policing and surveillance, but in the sense that it is constantly being regulated in the market. Can you talk about this element of the work? What was your initial reaction to the censorship, and how do you feel looking back on it?

M+KO: We had an ongoing conversation with eBay’s bots about appropriate sales and all of the ways it was already selling Blackness through figurines and other paraphernalia. It ultimately felt appropriate that our intervention on the sale of Blackness at the marketplace was met with resistance. What else would happen? Dialogue with people from around the world continued over email and in interviews about the function of Blackness in its intersection with gender, the internet, and the marketplace. The work continued.

AD: Mendi, can you discuss Keeping Up Appearances? What prompted making the work?

M+KO: Keeping Up Appearances, which we called “a hypertextimonial,” is a text-based, net.art work that appears to be a poem with a lot of white space. If the viewer moves the cursor over the white spaces, text that has been rendered in white turns pink. The viewer can see that the work is instead a narrative told in a straightforward manner. The story is about sexual harassment. The only text that is constantly visible are the parts that do not recount harassment, indicate discomfort, or reveal emotion.

The two of us had been having a lot of conversations about form across creative contexts. We had been working on a few projects that reflected on color as code, on the social meanings ascribed to colors. We were also talking a lot about Raymond Saunders, the painter who published a pamphlet called “Black Is A Color” in 1967. Saunders is an abstractionist. That pamphlet is typically read as a pushback on identity politics and sometimes as a disavowal of Black Art, or art that is valued or understood to be Black because of its subject matter. But Saunders was also a family friend and Mendi had grown up with paintings of his from that time that were abstract but also often dealt with Black subject matter. We were grappling with the ways certain formal choices could have both aesthetic traditions and social meanings. So we were thinking about race and gender and the codes by which people accessed that, and the ways people performed gender in language, and decided to performing hiding in language and think about the ways and reasons people use language to say more than one thing at a time. Keeping Up Appearances came out of that exploration.

AD: It seems that you (Mendi) have a vested interest in exploring poetry and written texts online. What makes this interesting for you?

M+KO: We’re both very interested in the ways that language performs in different contexts. Mendi comes from a background as a poet, and that’s one of the reasons that there is writing in our work, but it’s a shared interest. And we have explored language and poetry online for the same reason we explore anything anywhere—because it’s where some of our life happens. That said, there are opportunities for interactivity, which may be performed or just implied, that allow for deep engagement. We have enjoyed exploring them in this medium, alongside all the others.