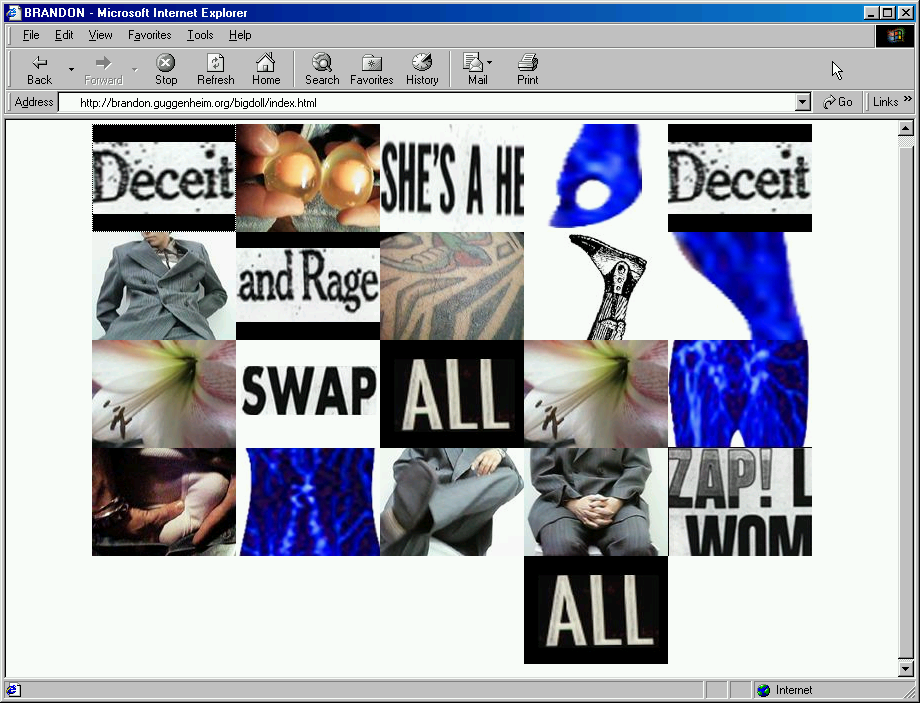

This interview accompanies the presentation of Shu Lea Cheang’s Brandon as a part of the online exhibition Net Art Anthology.

-

On June 30, 1998, the Guggenheim launched its first artist project for the web: Brandon. For artist Shu Lea Cheang, the artwork was a process of “becoming,” and included multiple authors while working against geographical and disciplinary boundaries. The artwork refers to the life and death of Brandon Teena, a young transgender man who was sexually assaulted and murdered in rural Nebraska because of his gender identity. The artwork released five years later, on June 30, 1998, as a collaborative platform, still undefined, inviting guest curators to illuminate Brandon’s story. An important part of the work was developed in association with Waag Society, an institute for art, science, and technology based at the Theatrum Anatonicum in Amsterdam. Built in 1691, the theater was first used by doctors to dissect corpses of dead criminals. Within this setting a series of performances were organized as part of the Brandon project. On March 20, 2017, I spoke with Shu Lea Cheang and Marleen Stikker, the director and co-founder of Waag Society, looking back at the evolving state of Brandon from 1998 to 1999.

Karin de Wild: Brandon developed between 1998 and 1999 as a “one-year narrative project in installments.” Two installments took place at the Theatrum Anatonicum. Let’s start with the first one: Digi Gender Social Body: Under the Knife, Under the Spell of Anesthesia (September 20, 1998). Can you explain the title and its concept?

Shu Lea Cheang: At the time, the real Brandon Teena could not cross the border of Nebraska. He was pretty much tied up in Nebraska, and I think in America people always say if you’re queer, you are not comfortable in this country’s state, you should go to San Francisco. But Brandon was never able to do that. So the idea with the Brandon project was teleporting Brandon onto the cyberspace. So in terms of “Digi Gender”: for me gender is not fixed. “Digi”: digital, there you can really free up the concept of gender. And “Social Body,” being the other part of the work, was inspired by this article by Julian Dibble, about the rape in cyberspace.1 So for me it’s about this kind of virtual community to create a kind of social body, a social space.

KDW: Marleen, why was De Waag interested in Brandon, in particular this installment?

Marleen Stikker: In 1994 I organized the Cyborg Festival, because of the Cyborg Manifesto of Donna Haraway that was translated into Dutch.2 We explored the internet as a cultural space and its artistic potential. The whole cyborg story was part of our world, our reference about thinking about cyberspace and uploading yourself to cyberspace. Brandon moved in this discourse between the still emerging idealistic idea of a new space, cyberspace, where we could redefine our sexuality, redefine the social, redefine power. On the other hand, gloomy visions that it was already starting to become a space which was not open. The work for me contextualized very well that moment in time.

KDW: For the first installment, a Netlink forum took place.

SLC: It was a public forum. I had invited people who studied gender to come and give a talk, and there was also sort of remote participation. Brandon, in terms of my own development of concept at the time was quite influenced by the whole Cyborg Manifesto, so it was about the “trans,” possibilities of “trans,” but it also involved embodiment and the body apparatus.3

It was totally on the web at the same time. All the chats were happening on the web, so you could participate on the web. But as far as the live event, it was not netlinked. I think technically we just could not achieve that.

MS: The virtual and the real really merged into each other.

KDW: The second networked performance took place in May 1999 and had the title Would the Jurors Please Stand Up? Crime and Punishment as Net Spectacle.

SLC: I did a residency at Harvard University at the Institute on the Arts and Civic Dialogue.4 At that time I was working with a lot of lawyers. Harvard was more like a real space; a real theater; real life; actual developments. They even hired a dramaturge to make it into a public theater performance piece. It was taking up all the court cases that I had researched on gender: some of them were raped, some of them got murdered. And the lawyers were doing a debate about all these cases. So at that time, it would become like a theater piece with the lawyers as the performers. After that development, I came back to Waag Society to stage the virtual court. For the virtual court everything got simplified. So there were questions that people had to agree on. Yes or no? Which one would you choose? Sometimes we had a hung jury, when people didn't come to an agreement.

MS: There was at that moment the idea that people could use software and the internet to brainstorm. They could add their ideas and they could do this anonymously. So it was an idea of the web as being an open space for contributions. I disliked most of these kinds of projects, because people were mainly presenting their own ideas. There was not a dialogue. So what I really liked about the whole concept [of the jury software in Brandon] that it was structured in a way that people had to discuss, they had to react on each other, they had to try to convince each other to not have a hung jury. The software was designed for debate and for real dialogue. Or you could be like the troll, making it impossible for people to come to a consensus. Until now I think this has been one of the most elaborate places in conversation on the internet.

I started in 1994 with the Digital City.5 This was the first news groups where ideas were discussed together on the internet. And they all failed. In every of these web news net groups people started blame and flame wars. From the early beginnings, the internet has been a terrible place for discussion. So my interest in this jury application was this very elaborate way of trying to get people in a constructive conversation. And then, of course, the topic was the Brandon case; very complex questions were at stake.

SLC: We started court sessions in the Theatrum Anatomicum, I remember it was with the rings still installed. I was doing the moderation, engaging people, joining in the jurors. It was an intense virtual experience at the same time. It was still a kind of public spectacle in a way.

MS: The moment that it started, we put the laptops on the structure. It became a virtual session as the screen absorbs you. We also scheduled only virtual version, so without people in the physical space. Also the clock was ticking, which was very interesting as a dramatic element in the whole spectacle. People had to come to a final conclusion within the hour.

KDW: How was the web, as a space for artistic experimentation, different in 1998 compared with today? Did you experience any limitations during Brandon, Shu Lea?

SLC: Now the question with Brandon was [it was] always kind of accused of being elitist exactly because it’s difficult to navigate, it takes a lot of bandwidth to, you know…you want to go through the roadtrip [part of the work], for example, and it always takes some bandwidth to navigate it. So I did have to answer a lot questions about the project being elitist, like who had the ability to watch this piece. I always say, “Well, it is a public piece, and it's supposed to be for the museum. You can go to the museum, you can go to the library.”

I think my debate for this was always like, at the time, it was the institution that had to promote this kind of work, had to provide the access to view the work. I think it was the same when I came to know the World Wide Web. The first art project I saw on the World Wide Web was actually Muntadas’s The File Room. And it was in Mosaic, and I remember I was in New York. This was 1994, and I was like “Wow, okay.” I had to travel to Columbia University to check out where the exhibition was happening in the library just to see it, just to browse it. And that was my first experience, so it’s not like at the same time the piece was particularly available, say, “Oh, you just stay at home visiting the web,” because the bandwidth doesn't allow you to do that for a lot of people.

So, yeah. Of course there’s this limitation, but I think in a way, what we tried to do at Waag was with such a team: program management, a developer, also a designer, it brings the project to a different level, like I’m not an artist alone anymore. I was in a creative industry. I was in such a management system with this residency. You really have a team of experts who work with you in every different aspect of it. So that’s a very different. Even with that I remember we struggled with that opening sequence of having the image to shuffle. We were showing images from the Guggenheim opening. We were beaming the Waag Society opening at Theatrum Anatomicum, and that was the first time we tried to do that.

But then in 1999 when we did the courtroom [performance], the virtual trial, and that was even more ambitious in a way that we called up a lot of jurors global-wide and tried to figure out the time zone difference to when all these different jurors could do the virtual call together. At that time absolutely we could not do any voice or image for the jurors, so it was totally by chat. I don’t even know how we did it. It was quite crazy with all this connecting, speaking about time zones, try to figure out people joining from Australia, the time zone difference so they can be online, and then the virtual calls taking place. It was actually quite ambitious at the time I think.

MS: The internet started in its public form, it started as a social environment where people started to collaborate and to meet. And a lot of tools and the interface were there to express ourselves and to connect and to interact with each other. But there were a lot of limitations because of bandwidth. We had this event We want bandwidth as an exploration of bandwidth.6 It was really a big issue and still is, I guess, but less. So I think that the things that we wanted from the internet were not always possible, because of bandwidth limitations and also some tooling that was not there.

KDW: Brandon was a multi-author, multi-artist, even a multi-institutional piece. What was your role as an artist, Shu Lea?

SLC: I’m doing the concept and direction. And so of course I’m quite involved with all the aspects of it. I also make movies, so I know that as a film production way. It’s very normal for me to be in this kind of system. Of course, the artist imagination is ahead of the programming reality, right? So there is always a discussion about what you want to do, cannot be achieved at this moment of time. So that was always such a challenge.

KDW: How was Brandon at the forefront in this rapidly changing technological landscape?

MS: Even today, people are trying to figure out what narratives are on the internet. What is storytelling? What is a narrative? What is a new construction? This was a collaborative work. There was a clear director and clearly Shu Lea was the person to create the narrative or the backbone of the project. But being able to collaborate in such an open way is still, I think it is very special. There's a lot of artworks that have been made with such an approach, but at that time, definitely it was totally a new way of creating work.

KDW: Shu Lea, could you elaborate on the narrative structure of Brandon?

SLC: It’s an open narrative idea. I was inviting different participants to join to fill in the narrative, the content. I had been doing video installation that always involve collaborating with performance, so I’m very used to collaborating with performance. I have always planned the project as multi-artist collaboration. It is by chance encounter that i got to “install” myself in several institutions: a residency at Banff Center for the Arts, a residency at Waag Society with its Theatrum Anatomicum setting, working with Institute on the Arts and Civic Dialogue at Harvard Law School.

How did the collaboration with Waag Society start?

SLC: De Waag was not even open yet. I think it was 1996…

MS: Waag Society Foundation was founded in 1994. We started working in De Waag in 1995 and officially opened on June 21, 1996.

SLC: I must have come around in that time, because I remember it was still under renovation. I totally fell in love with the space, the Theatrum Anatomicum, and the plan to develop it into Waag Society, an institute for old and new media. I became one of the first artists in residence in Waag Society. In 1998-1999, during this whole year, I was mostly at Waag Society developing Brandon.

This installation by Atelier Lieshout, which featured a revolving webcam, was used during Brandon’s launch event on June 30, 1998 to upload live images to Brandon from the Theatrum Anatomicum in Amsterdam.

KDW: On June 30, 1998, the launch of Brandon took place at the Guggenheim Museum (New York) and simultaneously with Bloody Merry Party in the Theater Anatonicum (Amsterdam). Both places were connected through a Netlink. What do you remember of this event?

SLC: The Theatrum Anatomicum installation was done by Joep Van Lieshout, so it’s a kind of a sculpture.7 On the top we actually had to take down the chandelier and replace it with a projector. So that's how you saw the surgery table in the middle, which was quite bloody. On the surgery table the billboard interface for the opening was projected.

MS: In the Anatomical Theater there was a re-installment of how [dead] bodies were dissected in this theater in the 17th century. It used to be an amphitheater. We have been discussing to bring back the amphitheater, but I think the rings were beautiful as it only gave back the spatial orientation.

SLC: There was a camera, a small webcam that was making a circle on the second ring.

MS: Yes, it was like a little train.

SLC: It was at that time, of course, so it was a webcam, but we could only grab still images. And that's what the interface was. So it just goes around the circle grabbing images of the audience that was present at the opening. I think the main thing for this first opening was the camera idea that was able to send images. The Netlink interface still exists, but the billboard should still be there too. I think it were different slogans that were being put on a billboard.

MS: De Waag was experimenting with teleconferencing. Before Brandon we did the Virtual Kissing project, where two audiences in different locations could video-kiss each other and the images where streamed and combined in both locations. We used this experience for the video/images exchange.

KDW: Shu Lea, what are your ideas about the future of Brandon?

SLC: The fact is that the topics of the discussion are still very valuable. I myself continue to work with gender. Currently, I am working on the project Wonders Wander for the Madrid Pride 2017 project. Calling it a “location based mobi-web-serial,” I am applying a GPS-guided mobile app to track homo-trans-phobic attacks with queer fantasia narratives embedded along the walks in Madrid. Maybe this is my updated version of Brandon’s roadtrip with mobile technology? For myself, Brandon is an open narrative. I do hope that Brandon can be further developed as an open platform to allow public upload. The new generation of non-binary gender can add some new perspectives to these on-going narratives.

KDW: Marleen, how would you like to contribute to safeguard Brandon’s future?

MS: Well, this is an interesting moment in time, because there is a lot of interest in the early days of the internet and especially in iconic projects. I think Brandon is an iconic project, an iconic artwork, and you can tell a lot of stories through the work. Guggenheim really takes it seriously; this time there’s a lot of work being done. At the Waag we have an archival project. There’s a reason to work on how we can contribute to it. So that means that we will dig further into our old servers. I think, especially the court session would be good. We really need a mix of people and expertise to explore how to deal with our archive. For example the digital legacy from 1994, like the Digital City, is now being archived with practitioners, the original creators and the University of Amsterdam. What we did is that we found an e-depot, which is big enough to ensure that when it’s in this depot, they will guarantee that also in twenty years, it’s still accessible. Because in twenty years, again, the machines that we want to read the stuff will be changed. So you need a organization that is committed to keep it alive in the coming hundred of years. At the moment we are overwhelmed by the requests for access to the remains of digital projects. We do not have enough resources I’m afraid, to fully fulfill this task.

Notes:

1. Julian Dibbell, “A Rape in Cyberspace,” The Village Voice, December 21, 1993. This article described a “cyberrape” that happened on the platform LambdaMOO, the repercussions of this act on the virtual community, and subsequent changes to the design of the program.

2. The Cyborg Festival took place at De Balie in Amsterdam (The Netherlands).

3. Donna Haraway, “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century,” Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (New York: Routledge, 1991), pp.149-181.

4. The Institute on the Arts and Civic Dialogue (IACD) was founded in 1997 by professor and playwright Anna Deavere Smith. It supported the development of artworks and projects specifically concerned with social conditions. It tried to establish collaborations between artists, activists, scholars, and audiences to develop works of art about vital social issues of the time.

5. The Digital City (De Digitale Stad, DDS) started on January 15, 1994 as a free net initiative making internet access available for a large group of citizens in Amsterdam. This resulted in the first online internet community in the Netherlands. For more information about the Digital City: www.dds.nl.

6. During the We want bandwidth campaign, European politicians were criticized for their policy on access and infrastructure for local producers of content. It was proposed that the European Union should get a stronger grip on the social and cultural components of existing European Information and Communication Programmes (ICT). For more information about this project: http://waag.org/en/project/we-want-bandwidth

7. The original design was by Mieke Gerritzen.