This essay accompanies the presentation of Mendi + Keith Obadike's Black Net.Art Actions as a part of the online exhibition Net Art Anthology.

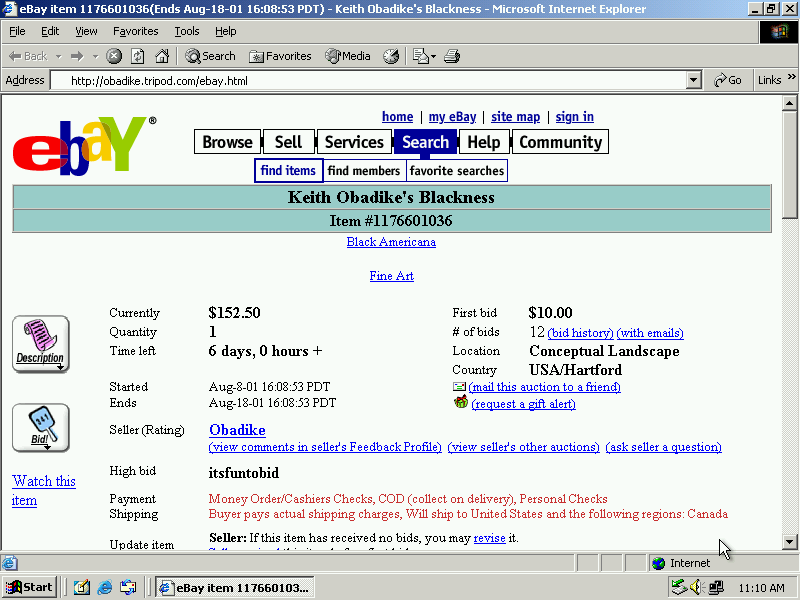

On August 8, 2001 Mendi + Keith Obadike listed Keith’s Blackness, Item #1176601036, for sale on eBay under the categories Black Americana and Fine Art. Ten benefits and ten warnings for this Blackness are outlined in Item #1176601036’s description, such as “This Blackness may be used for creating black art” and “The Seller does not recommend that this Blackness be used in the process of making or selling ‘serious’ art”. The auction of Item #1176601036 was set to last ten days, but was removed by eBay after four days, when that company decided that it was inappropriate for listing on its site. In an interview with Coco Fusco in 2001, Keith Obadike tells us that he “didn’t really see net artists dealing with this intersection of commerce and race,” and that he “really wanted to comment on this odd Euro colonialist narrative that exists on the web and black peoples’ position within that narrative.”1 As part of the Obadike’s Black Net.Art Actions, Blackness for Sale aimed to “explore the language of color and its relationship to art, the body, and politics.”2 Blackness for Sale can be read as a critique of colonial encounters and the commodification of blackness, from the auction blocks of racial slavery to the online circulation of Black Americana and the consumption of items of distorted blackness. It is, then, an interrogation of categorization and the negation of Black life.

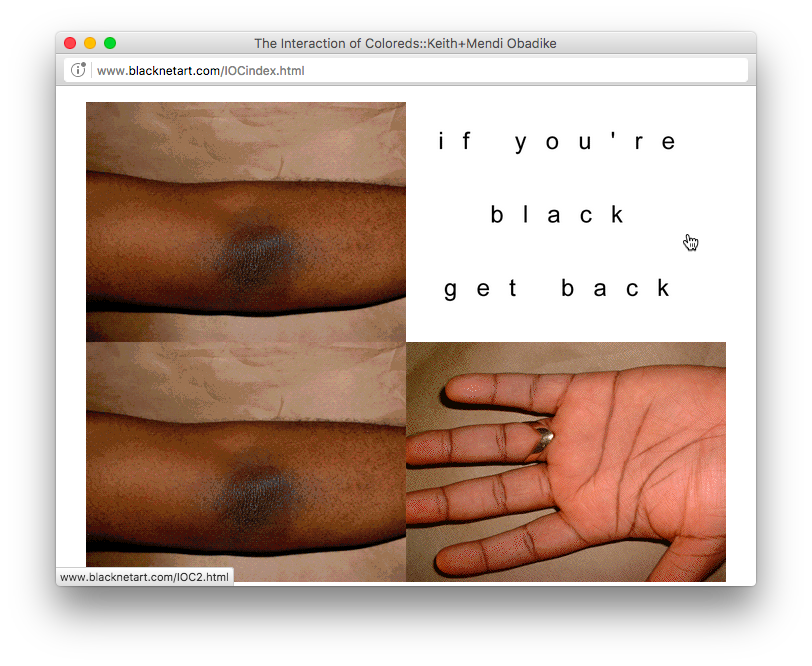

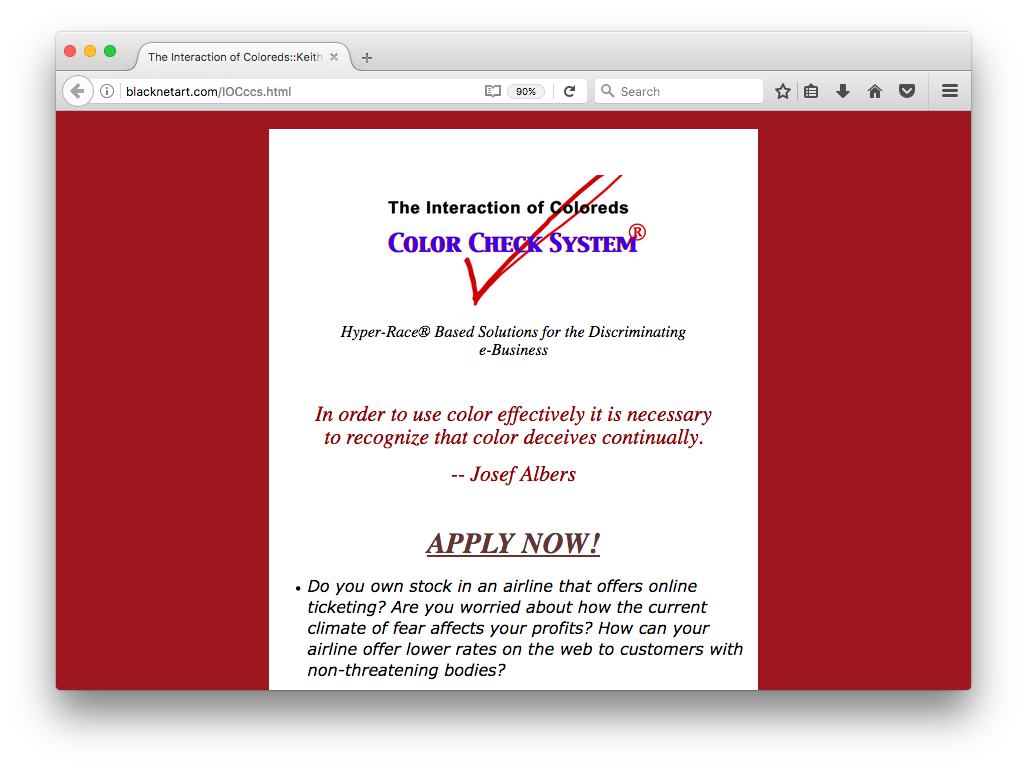

The rules that govern the classification of the human by way of “social filters,” online and off, were again taken up by Mendi + Keith Obadike with their 2002 piece The Interaction of Coloreds.3 On the dedicated website for this work from Black Net.Art Actions, photographs of hands, elbows, the back of the ears, and other body parts appear in a 2 x 2 grid formation in quick succession. These body parts are of the artists, with a brown paper bag (test) as the backdrop. Scroll over the top left of the screen and the phrase “if you’re white you’re right” appears. Long before I knew of blues musician Big Bill Broonzy’s protest song Get Back, I knew the line “if you’re black, get back” served as a warning and made clear the racist color coding of our past and still present social order. Click anywhere on the 2 x 2 grid and users are taken to the main page of IOC Color Check System® where they are encouraged to “protect your online community from unwanted visitors” and to apply because “websafe colors aren’t just for webmasters.” Click again and users are taken to an information page for IOC Color Check System® and told that “in this fast-paced, ever-changing world of e-commerce and online communities, who can afford the time and embarrassment of taking or administering a brown paper bag test in public?” and “Wouldn’t it be refreshing to get trustworthy color info like John Smith, #FFFFFF (read: true white) when you receive an email?” Answer a series of questions (“Has anyone ever checked for your color behind your ears?”) and follow their strict JPEG guidelines for uploading and users will receive a dedicated hexadecimal color code for the purposes of verification, identification, and measurement of one’s worth.4

In almost every undergraduate course that I teach on surveillance I share with the class Blackness for Sale. I see the students nodding their heads, some chuckling, when they read it. It’s so familiar to them. More recently and quite often, I’ve had to explain to them “why Florida?” in the warning “The Seller does not recommend that this Blackness be used while voting in the United States and Florida,” as many knew nothing of hanging chads, the recount, and Bush v. Gore. They almost always wonder aloud what would happen if Mendi Obadike’s Blackness was “for sale” instead, and this year we talked about street harassment, objectification, cis-normativity, reproductive injustice, gender-based violence, and the African American Policy Forum’s #SayHerName campaign that focuses on police violence against Black women and girls. Speaking on this question of gender, in that same interview referenced above, Keith Obadike notes that “with this project I think most people read my black maleness as normative and by default ungendered just as whiteness is often read as unraced. I think black womanness is a much harder sell. Once you add the idea of sexism to this list of warnings it becomes much more complicated.”

On August 8, 1951, fifty years earlier to the day that Keith Obadike’s Blackness was put up for auction on eBay, thirty-one year old Henrietta Lacks checked in to John Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore for the last time. By that time her cancerous cells had already been taken from her by way of a biopsy, without her knowledge, and set to become the HeLa cell line, now a most profitable commodity within biomedical and genomic research and pharmaceutical patents. The HeLa commercial cell line, the afterlife of Henrietta Lacks’s cancer cells, subsists within, as Marlon Rachquel Moore tells us, “a state of bioslavery” where,

Henrietta’s motherhood yields no financial benefits for her heirs. On the cellular level, then, the medical establishment subjugates Henrietta’s reproductive labour so that generations (strains) of HeLa perform as breeder slaves (bio-objects) in laboratory colonies all around the world. This irony is not new, for Black women have a complicated history of maternal and reproductive rights that further links HeLa’s biofuture to this country’s racial past.5

Fifty years apart, though not one and the same, Blackness for Sale and HeLa, however, both point to the ongoing racisms of unfinished emancipation in interesting ways—one creatively theorizes the conditions of Black life, the other serves as a notice of the vulnerability and reproductive injustices visited upon Black women and what could happen when that which is derived from Black life (and Black death) is made patentable. What are our responsibilities for racial justice when we factor in the specificities of Black womanhood?

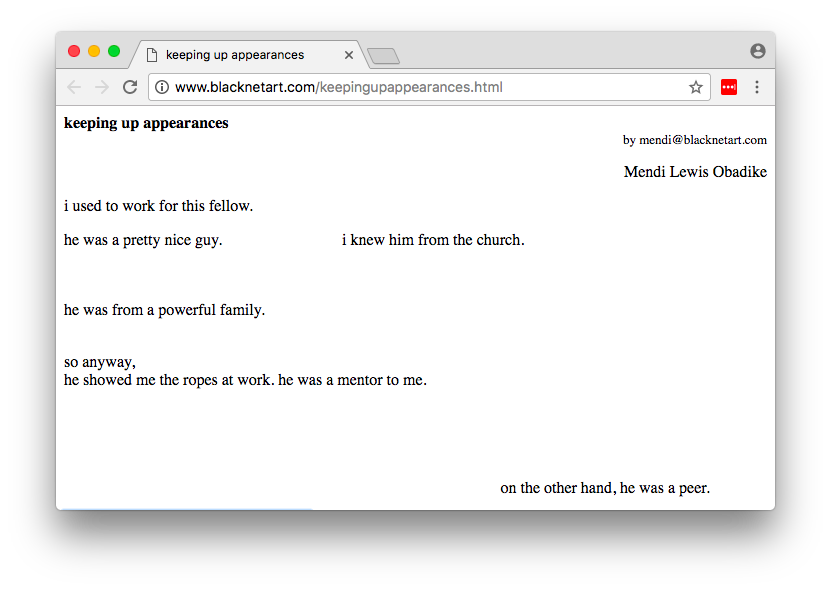

I look to Mendi + Keith Obadike’s hypertextimonial Keeping Up Appearances, now over fifteen years from when it first appeared online, for a guide to start to answer this question and that of my students posed above. In this piece, Mendi Obadike contends with power, violence, and investments in respectability by way of redactions and disclosures to “get at a way of telling which says: ‘this is what i want to say’ and: ‘i do not want to say this’ at the same time.”6 At first look, unremarkable, with minimal text on the page, it is seemingly a short story of mentorship. But in scrolling over its blankness, that which was redacted—the sensitive data—comes into bright pink view. This revelation demands of the reader to read differently and to imagine the simultaneity of the protagonist’s other story, this one a kind of vulnerability that is often hidden in plain sight. The kind of story where we are made complicit by our own acts of looking away. If a testimonial is a form of witnessing, then the hypertextimonial form, in this case, calls on us not to look away from the truths encoded in its form.

Mendi + Keith Obadike’s Blackness for Sale, Interaction of Coloreds, and Keeping Up Appearances all, in different ways, “get at a way of telling,” and telling on, the structural violences coded on black life forms.

Notes:

1. Coco Fusco. “All Too Real: The Tale of an On- Line Black Sale: Coco Fusco Interviews Keith Townsend Obadike.” September 24, 2001. Accessed April 25, 2017, http:// blacknetart.com/coco.html.

2. Keith + Mendi Obadike. “The Black.Net.Art Actions: Blackness for Sale (2001), The Interaction of Coloreds (2002), and The Pink Stealth (2003), pp.245-250. In re:skin, edited by Mary Flanagan and Austin Booth. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2006.

3. Ibid., p.248. Social filters being “the systems by which people accept or reject members of a community.”

4. Interestingly, in May 2016 a group of software researchers issued a call to the Unicode Consortium for software standards on the issue of skin tone modifiers for emojis. Taking particular issue with the Consortium’s use of the Fitzpatrick scale’s human skin color classification schema, the group warned that ignoring the scale’s colonial lineage and applying it to emojis “is emblematic of implementing a standard without careful examination of its scientific, political, cultural and social context of production.” (http://possiblebodies.constantvzw.org/feedback.html)

5. Moore, Marlon Rachquel. 2017. “Opposed to the being of Henrietta: bioslavery, pop culture and the third life of HeLa cells.” Medical Humanities. 43: 55-61.

6. Keeping up Appearances (http://blacknetart.com/keepup.html)