This essay accompanies the presentation of Cornelia Sollfrank’s Female Extension as a part of the online exhibition Net Art Anthology.

Michael Connor: How did you hear about Extension?

Cornelia Sollfrank: It was announced in spring 1997. It was shortly after I came back from New York, where I had a scholarship to research internet art in 1996-97. As the field was not so vast back then, I had the feeling that I had a quite good overview of what was going on. I knew a lot of people personally because I conducted interviews and attended the spaces like The Thing. Of course, Mark [Tribe] from Rhizome and many others were active at the time. Postmasters gallery, of course, was showing that stuff, especially Tamas Banovich.

That was the context I explored when I was in New York. I came back and one of the first things that I encountered was this call to create the first competition for internet art.

My interest in that regard was mainly based on the idea that the internet would not only be a new medium for production but in particular also for dissemination of artworks, or interventions, or whatever. Things we wanted to do, we could share amongst ourselves and build our own context.

That was, to me, the fascinating moment of the internet, to be independent from traditional art institutions. Then in that very moment, as I kind of grasped that and understood and got really totally excited about that, the museum [Hamburger Kunsthalle] came with their call for finding the “best net art work.”

It’s a gesture of appropriation and reintroducing these mechanisms of inclusion, exclusion, quality, definition of quality, giving away prizes and all that stuff that we wanted try and get rid of. It was so totally against my expectation or my intentions of what I wanted to achieve with net art.

This competition [Extension] was the first of its kind and it was the most obvious attempt from an institution to get hold of this scene that was independent—that could live and did very well outside the traditional art institutions.

MC: So for you the issue was more with the institution’s embrace of net art as a whole than the representation of women within it?

CS: I just received an article, this morning, where Female Extension was discussed, and they said my intention was to bring more female net artists to the museum. That was not my intention. My intention really was to destroy the competition or at least disturb it in such a way that it would become obvious that there is a critical energy or there is something in the net that is not happy with what they are doing there.

MC: How did you go about destroying or disturbing it?

CS: I decided to go with the idea of flooding. I created 300 female net artists. It was, for me, a given that it needed to be females, but that was more a side aspect. For me the main aspect really is the institutional critique aspect of the work, of the intervention.

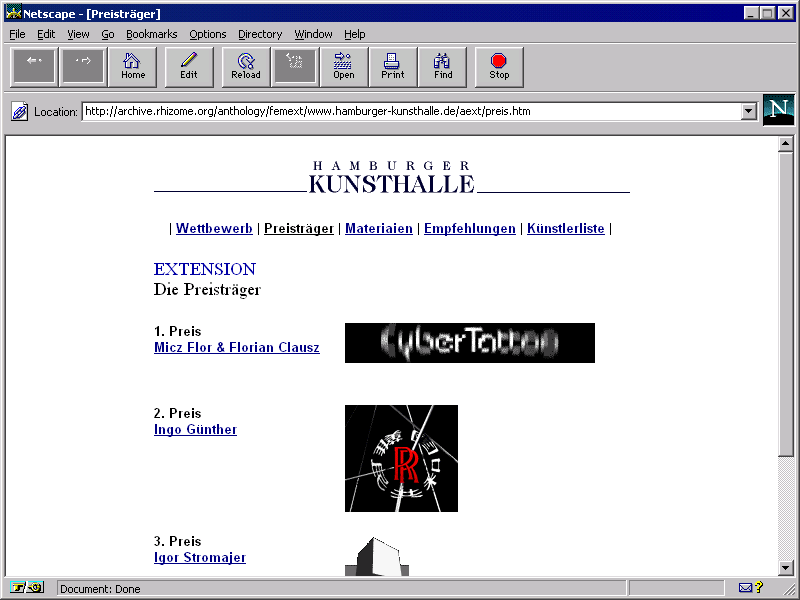

Announcement of Extension winners from Hamburger Kunsthalle's website, 1997, as seen in Netscape 3.

MC: How did the entry process work?

CS: First I had to create all these names, which was also not so easy because there was not the material online that we have now. I went to a local post office and was going through their international phone books, and was looking up names in different countries that were plausible, and last names connected to a real existing address in the particular country. There was quite a lot of idiotic work to do. It was not very interesting. Then I registered all of them.

Actually it was not so easy also to get functioning email addresses back then, because there was no Googlemail or anything where you could just register for free and get an email address. The commercial ones, like CompuServe, were very expensive.

I was really lucky that I was in touch with a lot of artists and groups and initiatives that were running their own servers and could provide me with email addresses. That was The Thing New York, Digital City of Amsterdam, Desk in Amsterdam, it was Internationale Stadt Berlin, which was an online project, it was t0 netbase and The Thing in Vienna, it was The Thing in Berlin as well, it was Ljudmila in Slovenia. Places we know now from the history of net culture that were early hubs of net culture and net art. They were all a part of Female Extension that’s often overlooked, they played a really important role.

I had hoped that the museum would already not be able to cope with these 300 entries because it’s not what they expected. They expected maybe fifty or something, maximum. But they were using the technical facilities of Der Spiegel. The museum wouldn’t have been able to process this [many entries] in any way.

It was automated and for each name I had registered I received a password. It was the requirement of the competition to upload the net art onto the museum server. That was one aspect that showed that they didn’t know what they were doing, because if you wanted to access an online artwork you would not ask for the data of the website to get uploaded on your server. You would just ask for a URL and then go there. They totally did not trust the sites that the artworks would be really online when they wanted to see them.

I think there was also, in the call, a defined maximum size of five MB. The data you would send to the museum could not have more than five megabytes.

For me, it was good because I would have had problems to really come up with 300 different URLs that still would be plausible. It was much easier to just create some data trash that had the format of the website. Just HTML sites that contained whatever, it was totally random.

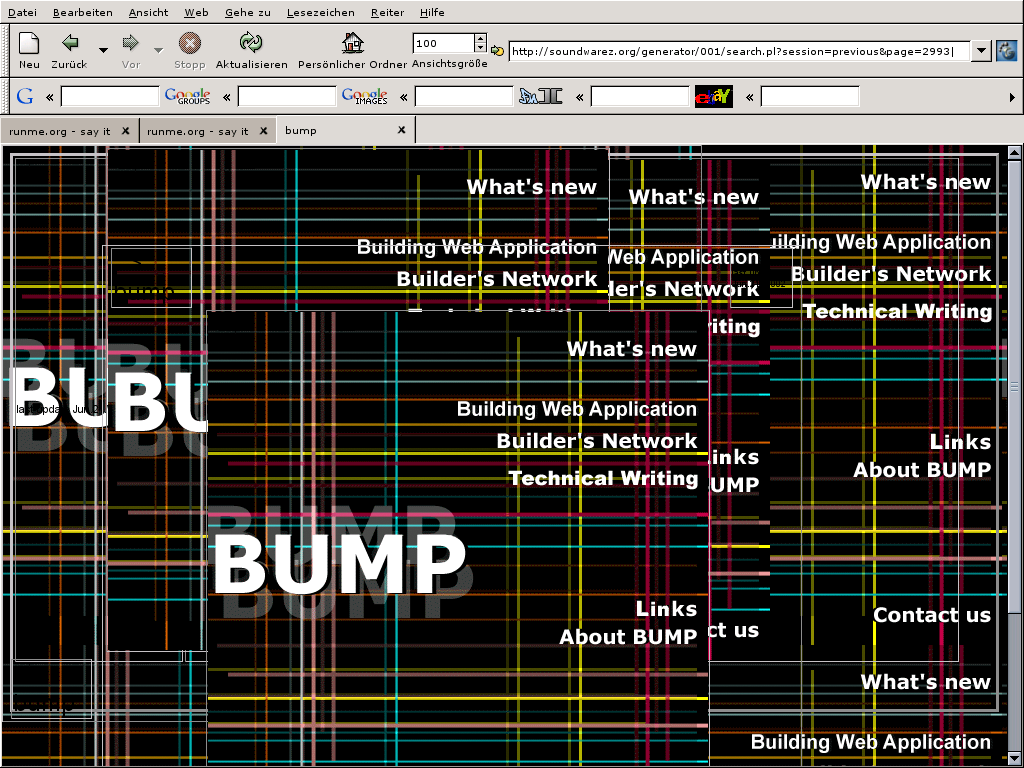

I decided to create 300 web pages by using the old technique of collage and applying it to a sham URL code. I just copied and pasted code from existing websites online into a new HTML file and saved it. Then I sent it to the museum. If you opened it in the browser, it would always look somehow interesting, you would not be able to figure out what it was because it didn’t make any sense, but it yielded some really interesting effects and graphics, whatever, structures and things and a lot of broken image icons and question marks and all kinds of things.

It looked interesting. I started to create these fake HTML websites by copying and pasting and doing that by hand. I found it a bit tiring. I was meeting a friend and told him about this thing. He suggested to automate it, to write a script that would do exactly that, go online, grab some HTML code from different websites and merge it into one.

That was actually the first version of what would later become the Net Art Generator. With the help of this program, we were able to really produce, in a very short time, a lot of websites and upload it on the museum server. They did not find anything irregular about that, so the museum just processed it, and each email address was sent a confirmation letter that the work was received and it would go to the jury meeting as scheduled.

Screenshot of image created with Net Art Generator, from runme.org software art archive.

The first press release sent out by the museum said, “Extension is big success. More than two thirds of the submitted works are by female artists.” That was quite funny for me to see, that they were really already advertising the fact that there were so many women who had entered the competition.

I know for sure from someone who attended the jury meeting that they really looked at all the works. They tried to understand what was going on, but of course they couldn’t figure out any sense in the works that I sent in, because they were just trash. There were so many of these sites and they all looked different in a way.

The idea that somebody would have been able to make an intervention or to create fake identities or something like that was not in their mind. They could have recognized a pattern, I think. A pattern of this kind of randomly combined stuff that made structures and created broken links and all that. I think that is the structure that becomes visible if you pay attention, and if you shift your attention from the actual content of one page to a structural aspect.

They didn’t, because they were not aware that something like that could happen. I think it still confirms what I had in mind, or what my suspicion was from the beginning: that they simply had no idea about the functioning of the internet, not at all.

The jury met, and because they could not really get any sense out of the works they just neglected them. They gave the three prizes away to male artists who had submitted works that obviously made more sense than what I had submitted. That was of course, I can imagine also for the museum, a little bit of an embarrassing moment when after the first press release they say, “big success, more than two thirds of the submitted works by female artists.” Then the next week, the three winners, all males, very funny. [laughs]

Cornelia Sollfrank at the Cyberfeminist International, part of Hybrid WorkSpace at documenta X, Kassel, 1997. Photo courtesy of Cornelia Sollfrank.

MC: How did you reveal your secret?

CS: I had the choice either to just let it go and have my own private fun with it, or to reveal it myself. That's what I decided to do and I wrote my own press release describing what I had done. I went to the museum press conference, which was very well advertised, there were about thirty journalists present and I went there and I handed out my own press release on top of all of the stuff of the museum.

That’s how the journalists found out and of course they all found it very funny so I got a lot of good press basically. There were making fun of the museum and they were making fun of the jury, and they were making fun of the curator of the museum and everything.

I got a lot of positive recognition and appreciation from the net art scene and from the net culture scene but the museum, the people from the museum in Hamburg, they never forgave me, never. They never spoke a word to me afterwards. They also gave up the original idea of Extension, which was to build a virtual extension of the museum.

Again and again there are art historians that do research on internet art, net culture, that get in touch with the museum and try to get information from them. Either they don’t get an answer or if they catch someone on the phone, the museum people totally deny having anything. It’s totally deleted from the history of the museum, does not exist.

They try to ignore it. It’s quite funny because it’s actually, the interest in the project, it’s actually becoming more and more. It’s not going away, but it’s just the other way around. It’s this historical project twenty years ago which was the protest of this first attempt from the art world to take over net art. It had become this iconic intervention.

MC: What about net artists, how did they receive the project?

CS: They laughed at it, they all laughed at it. Jodi said, “That’s so cool!” I knew most of the net artists at the time. I know that there was a discussion, whether they should participate or not. They were all very unhappy, but on the other hand no one could actually make any money with what they were doing.

That’s how you discipline artists or how you corrupt them. You put a few thousand dollars here and say, “Come on, jump,” and then you get the money.

Some decided not to send in something, others did but they felt very unhappy. I think Alexei Shulgin, he didn’t send anything in. I think Jodi did, but if I remember right, they made a compromise. They said, “We sent something but we didn’t send our best work,” which didn’t make any sense at all. [laughs]

That would be another thing I think, to do research on. I think it would be fun to talk to the net artists who were around back then and ask them how they remember it and if they participated or not. I don’t think there are any files left in the museum.

MC: This took place after Vuk Ćosić’s theft of documenta X. Do you see those projects as being more or less sympathetic in their aims?

CS: Vuk’s intervention was after, but in the same year. The call for Extension came out in spring and then in June, document X opened. Vuk’s intervention was at the end of documenta, in September.

In one space, documenta X presented net artworks. That was totally funny. I wrote an article about it but I didn’t make any photos of it. It was just a room full with computers and people could sit down and click the websites.

The funny thing was they were not connected to the internet because the curator was afraid that people would just check their emails or browse on the internet.

It was also documenta X where the Hybrid WorkSpace took place, curated by Pit Schultz and Geert Lovink, where we had the first Cyberfeminist International. It was a very busy year with a lot of important stuff going on.

There was a lot of criticism regarding the presentation of net art in this really totally inadequate way at documenta X. Then again, the Hybrid WorkSpace was a much appreciated context, as far as I remember, because it offered a real working situation and offered a lot of resources for ten different groups to meet and work together. Each group had the space for ten days and they could really work on what they found important, and you have an international audience, all funded through documenta X.

That’s where we had the first Cyberfeminist International, which was a great opportunity for us to have. We had the feeling with the Cyberfeminist International that the resources and the attention we would get through documenta X would exceed the compromise we were making by dealing with the art world. We could really do something. It was not about dropping a finished piece of work that would then be appropriated by the art institutions. It was really about meeting people and doing something together, and it had a lot of impact. I still think it was very good that we went there with the Cyberfeminist International.

Cyberfeminist International, part of Hybrid WorkSpace at documenta X, Kassel, 1997. Photo courtesy of Cornelia Sollfrank.

MC: What was going on in the cyberfeminism conversation at that time?

CS: Cyberfeminism started in the early 1990s with Sadie Plant mainly and VNS Matrix and it was very much focusing on the body. It basically was a very essentialist approach to conceive a relationship between the female body and digital technology.

I just reread Sadie Plant and reread also VNS Matrix and reviews of that because I published an article on cyberfeminism, which is called “Revisiting The Future” because [in the 1990s] cyberfeminism was called the “feminism for the 21st century.” Having arrived in the 21st century, what actually happened to this feminism of the 21st century? It seemed to have gone nowhere or it’s not so obvious where it has gone.

In 1997, we founded the Old Boys Network, the cyberfeminist alliance in Berlin. The Old Boys Network organized the First Cyberfeminist International at the documenta X Hybrid WorkSpace. Our idea was to appropriate cyberfeminism and free it from this essentialist load of the early phase and open it up to include many other feminist aspects, which were also, for example, more materialistic. Economic considerations, the material basis of the internet, and many other aspects that were not present in early cyberfeminism.

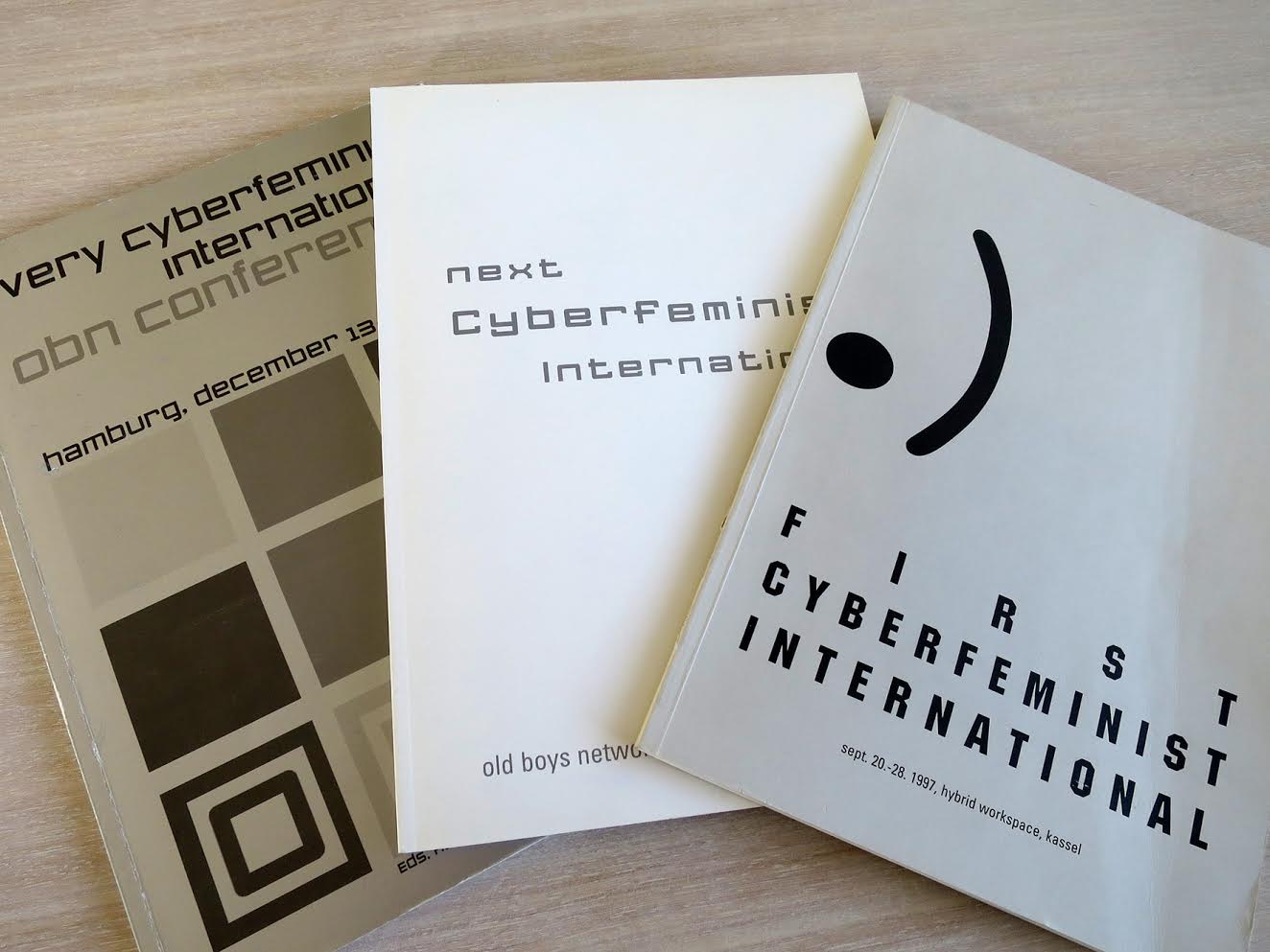

Publications from Cyberfeminist International. Photo courtesy of Cornelia Sollfrank.

We were trying to practice a very pluralistic approach, I would call it now, which is in a way also questionable, but that was at least a first step, or that was a step after the first phase. We were active for five years and we held three different international conferences and published all the readers and had this discussion.

There was then, I think, a bit of a cluelessness on all sides how we could continue because it would have been needed from the pluralistic, very wide platform idea of Old Boys Network to really narrow it down again and see what the political concepts were, certain people can agree on and political goals and then continue working again in smaller groups, which partly happened, only partly I think.

MC: So the cyberfeminism conversation and Old Boys Network was one aspect of the net’s ability to allow you to create your own context, and you saw projects like Extension as a threat to this type of activity?

CS: I don’t know, I think one interesting question that I’m always asking myself in relation to net art is, what is the relationship of net art to the art world?

There is no good theory and no good analysis of this, because very often the whole of net art is said to have been critical of the institution, which I don’t think was the case. A lot of early net art was very modernist, interested in exploring the materiality of the media and playing with that, pushing the material to the limit and making aesthetic experiments with it, which is fine—it’s just not institutionally critical.

A more profound analysis—what is the relationship between net-based art and the art world?—until today doesn’t exist, in my opinion, or only in very fragmentary aspects.

MC: Increasingly I think the question is flipping. How does the art world accommodate this juggernaut of internet culture?

CS: My theory is that currently net art is used to give credibility to postinternet art in this historical trajectory. In my opinion they have nothing to do with each other, it’s a total mistake, but I think it’s intentional because in the art world there is this kind of reputation around net art as something authentic and important, work of pioneers if you want, which postinternet art doesn’t have to a large degree. I think here net art really serves a purpose to upgrade, give more credibility to postinternet art.