This essay accompanies the presentation of Vuk Ćosić’s Documenta Done as a part of the online exhibition Net Art Anthology.

In the mid-1990s, a network of artists, including Ljubljana-based Vuk Ćosić, came together at conferences and on mailing lists to develop the concept of “net.art.” A number of these artists were involved in documenta X, the 1997 edition of the major exhibition held every five years in Kassel, Germany, that included a particular focus on net art and culture. Following the exhibition, the news circulated that the exhibition’s website, which included browser-based art and online forums, would be taken offline and sold as a CD-ROM. Before it disappeared, artist Vuk Ćosić quickly copied most of the documenta X site to his own server, Ljudmila.org, and circulated a mostly fake press release about his act.

This interview took place via Zoom in February 2017.

Michael Connor: So were you actually in documenta X?

Vuk Ćosić: No, no. They selected, I believe, Heath Bunting and Jodi from our little band. And we also had a thing in the Orangerie in that one summer [1997]. All of our mailing lists had a week each, something like that. And I was preparing a couple of those as well.

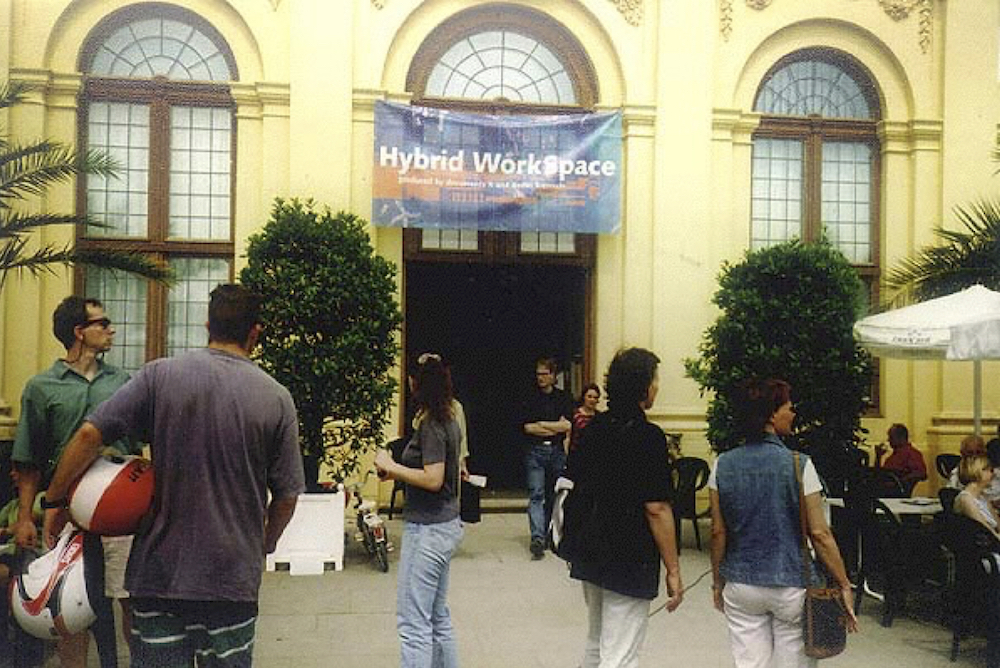

MC: That was called the “Hybrid WorkSpace” right?

VC: There you go. When you look back, you know, all these R2-D2-type names of things...everything had a robotic name. So, yes, this was a hybrid workspace.

MC: Can you tell me about Hybrid WorkSpace?

VC: Oh, it was like a prolonged festival. Some of our German friends had a way to influence the makers of the program. So everybody got a week’s time there and came up with a bit of an intervention. I remember [the email list] Syndicate was issuing immigration visas, or was it stamps in the passports? Everybody came up with their own thing. Just to spend the investor’s money.

Exterior of Hybrid WorkSpace at documenta X, 1997.

MC: And you were there as part of Syndicate?

VC: I can’t remember if it was Syndicate or Nettime. Because it was all together, it was like, which scheme do you use this week, or this time? It was more about creating an alibi to work in that space. And it was used by this super fluid network of people that kept meeting every week in another city. So sometimes you couldn’t even remember the actual alibi used this time around. Honestly, especially twenty years later, this is how I remember it.

MC: I know that you have talked about how you think about net art as being very much about this community of people. Is it possible to evaluate the success of Hybrid WorkSpace versus other programs like that? Was it successful?

VC: Well, Hybrid WorkSpace was not the place of origination of anything. It was like a gig in a bigger club. But all the primary ingredients came about in smaller venues and in more intriguing, far more interactive spaces. This was like having a shop window on Carnaby Street, you know, this was like, “Okay, now let’s go there to that big fancy place and try to reenact some of the weird things that we are doing for a couple years now.” It wasn’t the place where anybody could bring a new, big idea to play with.

MC: Where were the more “grassroots” venues where people would bring their big, new ideas?

VC: There were smaller meetings. Heath Bunting organized those at Backspace [a London internet club and space], I recall. There were a couple of those in London. One good one happened twice in a row in Budapest in 1995 and 1996...it happened three times actually. But I didn’t go in ’94. I’m sorry. Maybe it was excellent, maybe that was the best one.

You had these gatherings where somebody like Jodi would come and say, “Look, we’ve just come up with this new idea, this new piece.” I remember Olia showing us for the first time My Boyfriend Came Back from the War, her one and only piece [at that time]. And also, I recall points when people came up with new work. Those were interesting, or spots where we had some really cool dialogue that later spawned some new work. Specifically in net art terms. Of course, there were other events that were great for articulation of discourse. Such as Next 5 Minutes in Amsterdam. That comes to mind. Or even DEAF, Dutch Electronic Art Festival. That was in Rotterdam and was organized in those days by Andreas Broekmann. So there were these slightly less glamorous, not even much less glamorous, events that were somehow hotter. Even Ars Electronica—it sounds crazy, but even there we had some juices flowing.

MC: Since we’re on the topic of this network, do you think of the Net.art per se meeting as also on that same continuum?

VC: This is called strategic humility. I intentionally failed to mention that one. But of course it was the most important one.

MC: [laughs]

VC: Nah, I’m kidding. The criteria there was, “Let me get everybody in Europe that uses that expression net art in the same room and see what happens.” The meeting was relatively superficial if I'm honest. We created a fantasy or a cult exactly because it wasn’t recorded in any way.

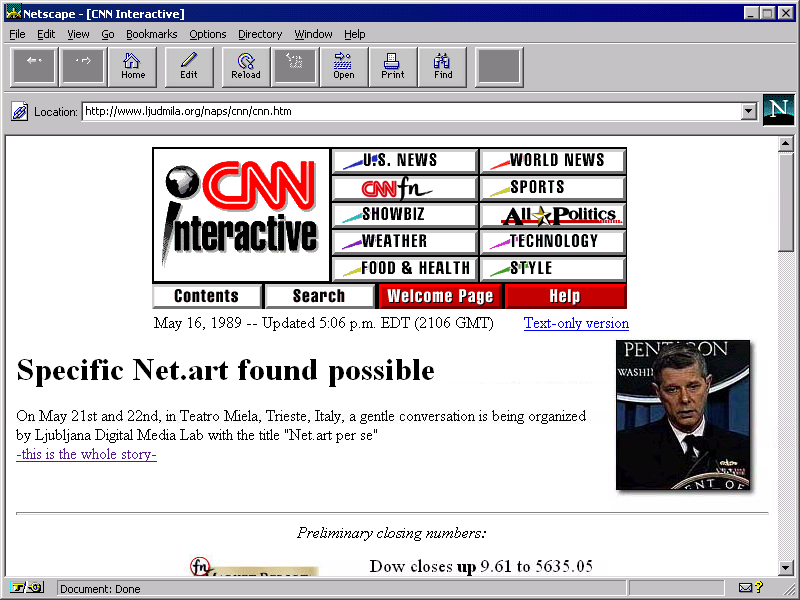

MC: [laughs] I think the website that you made might have had something to with its legendary status.

VC: As a matter of fact, [it was the] first time I used this message “View, source, copy, paste.” You know, literally copied four little websites and created the website for the event. The same gesture that I used a year later for Documenta Done. Only, for documenta I didn’t even change anything. The documenta was a sacred directory.

MC: I remember you copied the site of CNN...

VC: There’s Yahoo, I believe AltaVista. And Cybercafe, Heath Bunting’s website. They’re inside those four questions about net art. What is net art? Global, I don't know. So there you go. And I like the fact...for instance the one about Cybercafe is a website of Heath Bunting, right? I like that it was meant to be a critique of a net art piece, and the critique consisted of liking it so much that I copied it one hundred times, very many times. So you can just scroll through the same website over and over and over again. Well, these ideas. Sorry, it looks banal today...

Vuk Ćosić, Net.art per se, 1996.

MC: Was the Net.art per se convening something that you had to get funding for?

VC: Well, it was done within a context of some small festival in Italy [Teatro Telematico]. And I knew the organizers and they said, “Would you maybe like to do something?” And I got some cash from the planner for some tickets. But it was all-in-all about seven or eight people who flew in and stayed with my Trieste friends. A very, very simple affair, and the contents of the conference was this website and then us walking on the beach and eating ice cream for a day and a half. Then having a panel at the end of the second day telling the audience what we spoke about while eating ice cream. And these were the questions. I wrote them. That really was the agenda. That’s it, that’s the complete format of the conference.

MC: Recently Olia Lialina republished an old article where she said that conferences were sort of a native habitat for net artists.

VC: Yeah, there was nothing else. We didn’t do exhibitions. We didn’t do publications or fiestas or parties. All we had were these and we gladly traveled everywhere. We were approximately of the same age, plus or minus three or four years, I don’t know. Twenty-five to thirty years old, not too many very young people. That was interesting. And the circus went on all the time. And we would do pieces continuously to feel that tempo. Like that drummer in Ben Hur. You would just do it all the time.

MC: Was there still some excitement about the documenta X exhibition, initially?

VC: You see, we were already very busy for a couple of years and by this time we’d all had our things commissioned by Ars Electronica and we’d been in touch with the money part of the art system. And we didn’t exactly love it. We liked it and we didn’t want it at the same time. The whole media attention and museum’s attention. So this thing in Germany, this documenta X thing, was not something we adored, really. It wasn’t like, “Oh, this is what I dreamt of when I was a kid. I wanna be this when I grow up.” Totally not. So obviously we were looking for mischief, ways to subvert it. So when they did the actual, physical internet show with a big, blue wall and the office furniture, obviously everyone had to make fun of that. And we did. But, when you think back, it was actually not exactly not the worst possible show, the way it was set up. I’ve seen much worse things since, much worse. With projections, with printouts, super un-interactive things offline. So that was actually an honest event.

MC: So you don’t consider it necessarily a failure as an attempt at gallery exhibition?

VC: No, I curated a “historic net art exhibition” [laughs] here in Ljubljana two years ago. It was called “Net Art Painters and Poets.” And it was an exhibition of different net art exhibitions, all kinds. And there were I think seven or eight, six or seven, installations, like reenactments. And the one from documenta X was I believe among the best, to be honest.

Net art section at documenta X, 1997, documenta-Halle, Kassel. Photo courtesy of Joachim Blank.

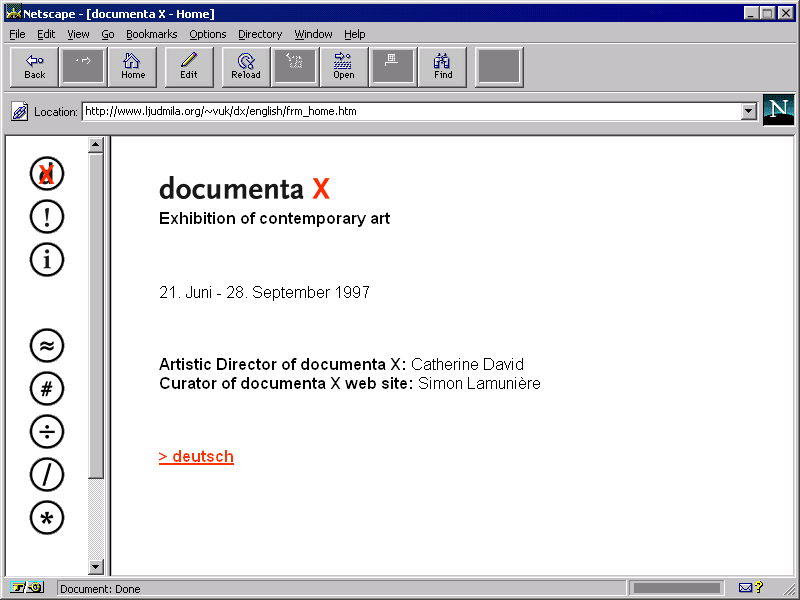

MC: To go back to documenta, the gesture of copying a website in particular has been taken much in the spirit of critique, as if it’s to symbolize the failure of documenta X.

VC: Unfortunately, it’s true. For most of ‘97 and ‘98 and even later, we were all in these very pompous, important museums everywhere. Pretty much in every museum I ever heard of. Which is great for the ego. But then you realize that you’re like one more column in the political correctness Excel file, where it’s very good to be in any of the minority or vulnerable groups, for a museum to prove how they’re dealing with contemporary practices or inclusiveness of their curatorship models and shit like that. But you end up in a museum where they don’t know where to switch on the lights, where there’s no technician there. I’ve actually been commissioned by several museums who would pay good money to produce new online work that got deleted from the server only two years later during some maintenance update. The museums were completely clueless and they were not at all questioning any of their wrong “business models.” Which is what everybody should have been doing in these last twenty years, instead of waiting for the catastrophe of digital disruption. And in reality, I think that overall those were very insincere little collaborations.

Vuk Ćosić, Documenta Done, 1997.

MC: But if documenta wasn’t the worse, what was it that created the need for this critique and lead you to think that the collaborations were dishonest work?

VC: Documenta was the biggest game in town at that time. So if you want to make a statement, you don’t do it with some irrelevant, small venue or joint. You just hit the big one, right? I remember the show itself outside the digital part of it. I remember documenta itself. And it was a grand affair every time. It’s a very big thing. Later I had some show in Kassel in that same, big museum, and I went to the bookshop and the archives. It’s tremendous, it’s tremendously important and for good reason. And not only because of Beuys. So I have lot of respect, and [the critique] wasn’t so much about documenta itself. It was about all the biennials and all the future biennials, too. And even by now, I’m noticing that when it comes to online art or art that’s serious, institutions don’t reflect the existence of digital realms. I’m not seeing big museums doing honest work. There’s been of course a few positive incidents that I do appreciate. But in archiving, in preservation, in displaying, in curating, and valuing online work, there’s a lot to be done, I believe. And museums are not the first ones to go there.

MC: That’s true. So it’s almost like, for you, the gesture is more about the failure of museums and institutions and biennials as a whole to really address this net art practices in a sincere way. Was your decision to copy the website and create this piece specifically triggered by their taking it offline and selling it as a CD-ROM?

VC: Yes, that was an immediate trigger. I’d already visited and everything, and this CD-ROM came up much later, about a month before closing the actual physical exhibition. But the atmosphere was clear and in our little mailing lists at the time, Rhizome included as a matter of fact, we were all discussing how this interfacing between our glorious practice that was unique and universal and eternal, and the old world of museum and galleries and art bureaucracies, how we have to lean down and look at those poor sods and be gentle and kind, because they’re having a hard time understanding what we're doing and they need some extra help and things like that. We were really pompous! Much more than I'm trying to imitate now. So [the CD-ROM] was like a little slap on the wrist by some guys who are failing to understand you. At that time we were so full of ourselves. It was like, there’s no way global evolution of art is not going to go this way and we simply happen to be the first guys around to do this. And these guys who don’t get it deserve a lesson. There was a little bit of that atmosphere too. The reaction was so swift. There was this press release in the evening and the next day I already had the work done. Like, zero effort and it was a clear thing to do. There was no dilemma whether the people from documenta deserved such a treatment, if this is what I hear in your question. Because they were the representatives of the big, wrong, old thing that we were all against.

MC: And why is taking a website offline such a rebuke to the net art practice of the nineties?

VC: Oh, come on. Private space, public space. It was the year of “unfenced prairies,” you know, it’s the American mythology, isn’t it? And then a bad guy comes, a farmer and fences off pieces of my prairie and I wanna pass my herds this way towards the Mississippi River, right? Is it not from John Wayne films? Anyway, we happened to believe these things. Even today I see benefits in open space more than in closed corporate spaces. Even this dialogue of ours is limited to forty minutes within our “freemium” business model of the commercial service we’re using [Zoom].

MC: How did you copy it?

VC: Because I’m not a geek, I’m an archaeologist, I started by copying them document by document, all those pages, and there were many. And then luckily my dearest friend and partner in crime, Luka, from our lab, said, “You silly fuck.” You see there is a four-letter word. It's wget. It's in Unix. I said, “It's in what?” And anyway, he did the rest of the copying for me and we put it all in my machine, in my little chapter on that server. And I wrote an funky press release and shot it out: “Lady DX Dies in an Attitude Crash.” You see, Lady Diana died in those days, in a car crash, so that explains the syntax.

MC: It’s interesting that you decided to make it a woman.

VC: It’s not about that. It’s just that, really at the time you couldn’t walk in the street without everybody telling you how sad and tragic it is that the English princess, queen-to-be, has died. That's all. All the headlines in all the newspapers were about that.

MC: The press release itself was kind of like part of your project?

VC: Totally, yeah. Heath Bunting helped me a lot with that. He made a good mailing list of international art media that looked very much like the list used by documenta. And I used it to send out a piece of information, saying that an Eastern European hacker stole the documenta website, these were the five buzzwords. Each and every one of them already guaranteed attention. So of course five of them in a row, hey, what could go wrong. Um, it was quite fast. I believe it was the next day that I got this mention or what was it, a little bit of an award by MIT for the “Most Notable Art Achievement of the Year” or something like that. It was really fast for the time.

“Lady DX Died in an Attitude Accident.” This was the first one sent to Nettime. And then there was a proper press release, with a subject line “Eastern European Hacker Steals ‘Documenta’ Website.” Then it was signed by Keiko Suzuki, which was our little pseudonym.

MC: Why would you call yourself a hacker?

VC: Because you know I had to be this Eastern European hacker. [laughs.]

MC: Of course.

VC: You know, for the article to pass. It came out in many newspapers around the world. I only saw a few of these. Also here in Slovenia, where they knew me already of course as an artist, they called me here from the biggest national daily and they asked me, “Look, we got this funny press release and it mentions you and we’re curious because this name here, Keiko Suzuki, no way it’s a real name.” And I said, “You got me.” I remember on the phone. I said, “You got me there, it's actually a pseudonym of Luther Blissett.” And the woman was super happy I gave her a little bit of inside information. But of course, Luther Blissett, he’s another pseudonym.

MC: Did documenta ever respond to the copying?

VC: Not formally. I was in touch with this German journalist called Tilman Baumgärtel. He [wrote] great stuff about net art at the time. And he was in touch with the people there, with Simon Lamunière. And they said they were kind of pissed but said that I was right and that they were not going to do anything.

There was a one day event at ICA in London. Something called “Archiving New Media” or something like that, where they invited a few clever people that I admire and incidentally they invited Simon Lamunière as a French curator of the documenta website. And me. So we had the public onstage, kind of a show-off. Nobody was shouting, “Jerry, Jerry, Jerry,” but the climate was there and everybody was expecting a wild fight. But this guy, Lamunière, he's actually quite clever and he simply had a few of these official statements: how this was the act of piracy aimed against the work of honest-to-God German, Swiss, and I don’t know what else, curators doing their best to promote this intriguing new practice. But still everyone hated him in the room. And it was insane. All I had to do was behave like Mt. Rushmore and people loved it. I remember the climate.

GIF by Vuk Ćosić made during a conference at the ICA, London, organized by Mute magazine.

MC: Is piracy an inherent part archiving on the web?

VC: Every act of using a website, is an act of copying a piece of content, and for me, it’s not piracy really. It was just let’s say a recorded session of visiting a full documenta X website. If this were a courtroom, I would use something like that as a defense. But, seriously, yes of course it was an act of digital piracy as the only possible gesture to preserve something in its natural habitat. I believe that online art can only exist online. It’s the only natural habitat. It’s context. If you put net art in a gallery, you’re taking art out of the context. This is why, for this particular piece, Documenta Done, I keep repeating that it is my little love child of Duchamp and Debord. I know this sounds like it’s for students of art history and I’m trying to sound like a proper Eastern European pirate today. So, tough. So it’s a ready-made detournement. This time it is a ready-made that’s incidentally found in a gallery and then taken back to the wilderness where it belongs. So, it’s a boomerang thing. It’s the opposite of the pissoir. And I were only a little bit more brilliant, I would actually be able to tell you by heart how you read pissoir in reverse, but it's way too complex. Roysop or something.

Header image courtesy of Vuk Ćosić