This text accompanies the presentation of Neen as a part of the online exhibition Net Art Anthology.

Neen is not a static thing, we cannot really put it down in words. When we will be able to do so, it will probably become Telic. Like the old miracle of Jesus walking on water: if he came back today and he did it again, it would be a sort of ‘déjà vu,’ ‘Jesus as usual.’ Instead, if he started swimming, most people would refuse to believe that he is actually Jesus.

—Miltos Manetas, 20041

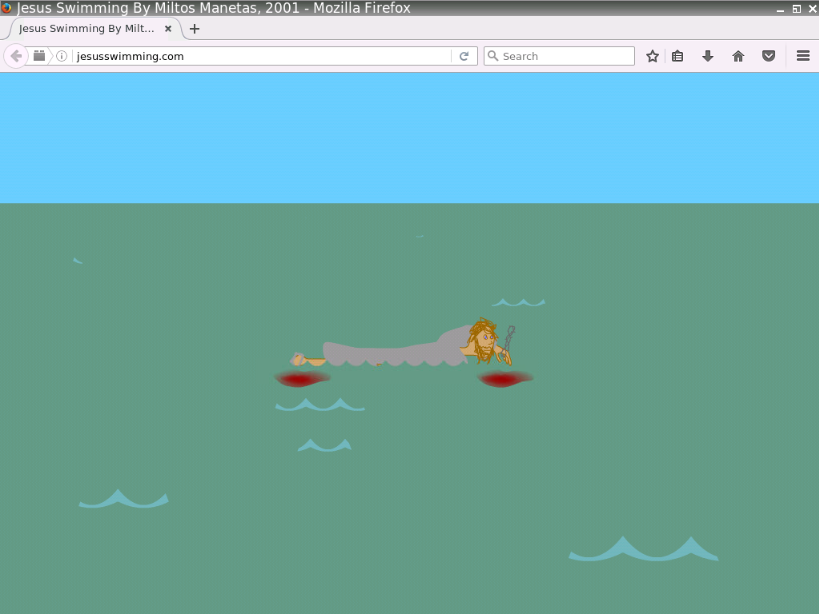

According to Who Is, the web domain jesusswimming.com was registered by Miltos Manetas on August 7, 2001. Visiting that domain, we are faced by a full page Flash animation, jesusswimming.swf, in which an hand drawn, vectorial man looking like Jesus swims in an endless sea, at the slow pace of a midi soundtrack. The drawing looks amateurish and careless, and the dominant aesthetics is flatness. In the html code of the page, the work is tagged as “Contemporary Art Jesus.”

When he made jesusswimming.com, Miltos Manetas was thirty seven years old, older than Jesus. And he was quite a successful artist, with works in good private collections such as the Dakis Joannou Collection, the support of respected curators like Nicolas Bourriaud, and participations in important institutional events. Born in Greece, at the age of twenty he moved to Milan, where he studied painting at Brera Academy. He started working with photography, installation, and performance. In 1994, he bought his first computer, and started making works with or about it. In 1995, he made a few oil paintings featuring fragments of computer interfaces, and in 1996 he was included in Traffic, the survey exhibition curated by Nicolas Bourriaud that helped to launch “Relational Aesthetics.” These works, together with Sad Tree—later turned into a website—marked his return to oil painting, a medium that he used to portray people, machines, and the both of them together: computer hardware, screens, web pages, games, cables, peripherals, people playing computer games. In 1996, he made his first videos modeled after videogames—later recognized as an early form of machinima—followed by his vibracolor prints, inspired by Zelda, Tomb Raider, and Super Mario. In the meantime, Manetas had moved to New York. In 1998 he launched Chelsea, an online art community designed by architect Andreas Angelidakis in Active Worlds, a 3D virtual world active since the mid-nineties.2

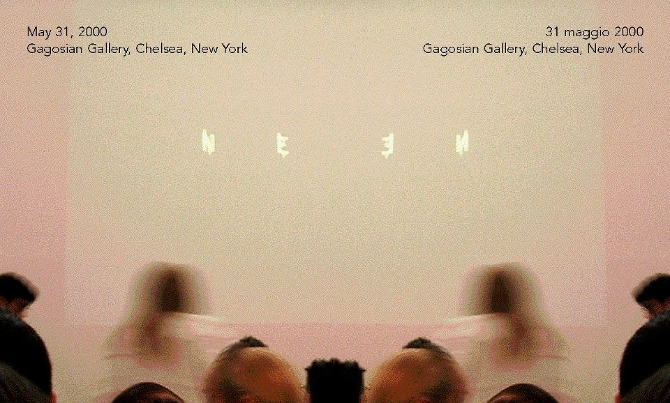

Neen announcement at Gagosian Gallery, 2000.

On May 31, 2000, with a press conference organized at the Gagosian Gallery in New York, Manetas announced that he had bought “a new name for the arts” from the California branding company Lexicon. The budget for the acquisition ($100,000) was provided by Yvonne Force from the Art Production Fund. The new label, Neen, was picked by Mai Ueda— at the time Manetas’s girlfriend, and the first self-proclaimed Neenstar, out of a long list of names sent by the branding company. The press conference took place in a room full of Warhols.

At the risk of sounding anecdotal, this long list of events stresses something that should never be forgotten, in order to understand Neen: unlike early net.art, it’s not the output of someone who refuses, contests, or bypasses the art world, but of a perfect insider. Manetas might have had his own, clear idea of what art is and should be—so clear that he bought a new name for it—but the world he is talking to, the language he’s speaking, the ways he behave—including his dialectical relationship with consumer capitalism, and with the worlds of fashion and commodities—are those of contemporary art. Neen mostly produced websites, perceived at the time as immaterial entries in a public domain; but all those single serving websites were placed on dot com domains, an extension then used almost exclusively by commercial ventures. The sites mostly used Macromedia Flash, a proprietary software popular among professional web designers who created fancy online vitrines for commercial companies, and hated by net.artists, who preferred the open code of html and javascript. Colorful, animated, and sometimes interactive, Neen websites are like paintings. They playfully and comfortably place themselves within a commercial realm, and present themselves as commodities (and Manetas was the first to collect them).3

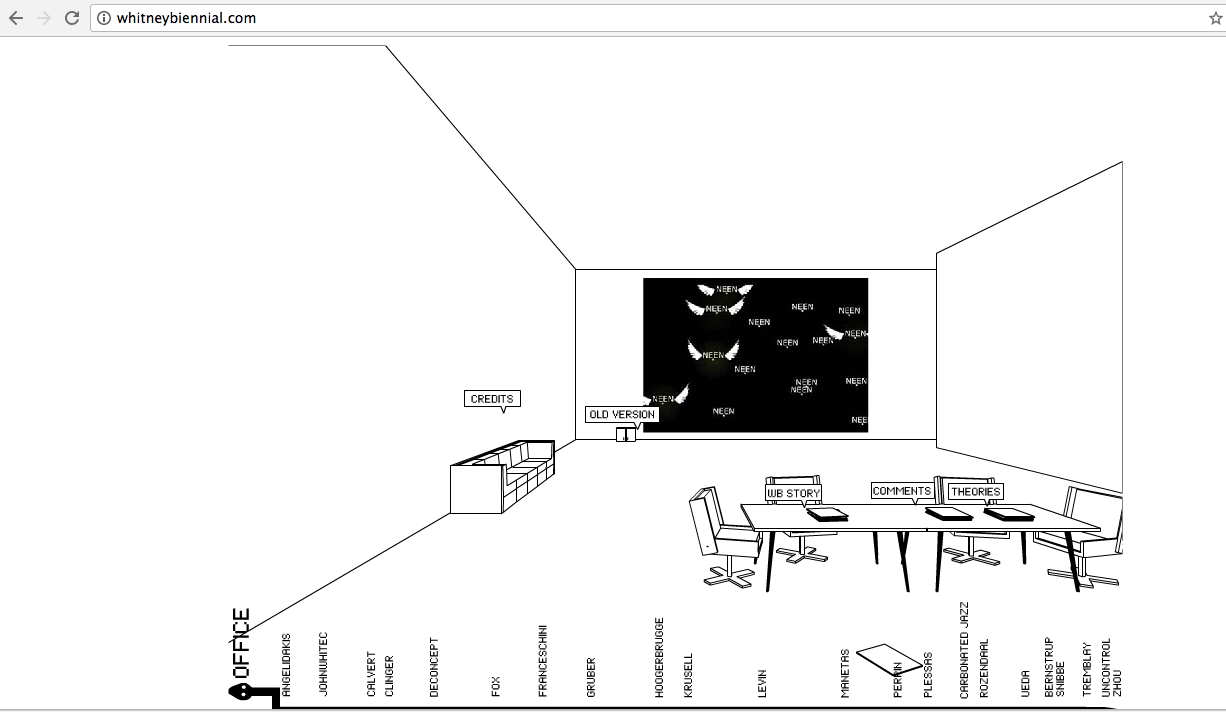

Neen squatted domains, but it did it as part of a domain name flânerie that brought them to purchase domains such as whywasshesad.com, dontcallmeelephant.com or elasticenthusiastic.com, not as part of a strategy of identity appropriation or as a consequence of a political agenda. Sometimes, the pure pleasure of adding a .com after a poetic sentence or a name, and owning it, was enough—look, guydebord.com is still available! Let’s register it! Some others, the owner or somebody else, could find the right content for the domain: so, francescobonami.com may deliver art theory, whitneybiennial.com4 may host an exhibition, and jacksonpollock.com may become an interactive generator of infinite dripping paintings.

Miltos Manetas, whitneybiennial.com, 2002. Screenshot created in Oldweb.today using Firefox 49 for Linux.

Another, important things we should know about Neen is that it isn’t a new name for net.art, or, even worst, for a subgenre of net art. Neen was commissioned and chosen as “a new name for the arts.” To Lexicon, Manetas and Force showed “a work by Gino De Dominicis, the Alessandro Dell’Acqua Men’s Collection 2000, two paintings by Anselm Kiefer [...] sodaconstructor [...] and above all works by Lucio Fontana.”5 This selection alone shows that Neen sits between contemporary art, fashion, and software. After presenting Neen in New York, Manetas moved to Los Angeles, where he started hanging out with the cyber elite and where he founded, in 2001, the Electronic Orphanage (E.O), a space in Chinatown that served as a working and meeting point for Neenstars and as an exhibition space for their works. There, Neen became an art movement, whose features are pretty easy to detect: single serving websites, playful animations, the ability to flirt with the art and the fashion system, etc. But Neen was born, and now exists, as a new name for the arts, chosen to describe what happens to art when it meets screens and enters the information age. As such, it may or may not have a life beyond Manetas and the Neen movement. Or, to paraphrase Manetas himself: if Surrealism without Breton became a trend and Communism without Lenin became a dictatorship, it will be curious to see where Neen will end up without Manetas.6

Even if Neen shouldn’t be understood as a subgenre of net art, it had a tremendous impact on the developments of net art itself. Manetas’s seamless postmedia approach, his way of going from paintings to websites, from screen capture videos to installations and performances, as well as his ability to speak the language of the internet without necessarily doing net-based work, was extremely influential for the younger generation that grew up in surf clubs starting in the early 2000s. Additionally, while early net art, though critical about both worlds, was still floating between contemporary art and media art, their separate traditions and their different ideas of art, net-related practices after Neen decisively embraced values, forms, and traditions from contemporary art. Finally, postinternet practices have inherited Neen’s realistic approach to the inescapable commodification of the internet, starting from the neutral usage of the .com domain.

--

Header image: Miltos Manetas, jesusswimming.com, 2001. Screenshot created in Oldweb.today using Firefox 49 for Linux.

Notes:

1. Quoted in Miltos Manetas (Ed.), Neen, Charta, Milan 2006.

2. Most of these informations are taken from http://timeline.manetas.com/.

3. Cf. Manetas Collection, online at http://manetas.com/manetascollection/.

4. About whitneybiennial.com, cf. Lucas Pinheiro, “The Flash Artists who Cybersquatted the Whitney Biennial”, in Rhizome, August 14, 2015. Online at http://rhizome.org/editorial/2015/aug/14/flash-artists-cybersquatted-whitney-biennial/. Although I agree with most of the in-depth analysis provided therein, I think Pinheiro’s interpretation of this project is partially invalidated by his attempt to situate it in a “net art only” tradition. Manetas is here playing with a system he belongs to, not hacking a system he doesn’t want to have anything to do with; whitneybiennial.com has, to some respects, more to do with Cattelan’s Oblomov Foundation than with RTMark.

5. In Miltos Manetas (Ed.), Neen, Charta, Milan 2006.

6. Cf. Miltos Manetas, “Neen Manifesto,” 2000. In Miltos Manetas, In My Computer, Link Editions 2011, p. 21.