This interview accompanies the presentation of Neen as a part of the online exhibition Net Art Anthology, and is part of a series of interviews with Neen participants. Other interviewees are Mai Ueda, Andreas Angelidakis, and Nikola Tosic. Domenico Quaranta also contributed an essay on Neen in the context of net art.

Lauren Studebaker: How did you begin collaborating with Miltos Manetas and how was the philosophy of Neen introduced to you?

Rafaël Rozendaal: I’m from the Netherlands and there’s this design group there called Experimental Jetset who did the identity for the Whitney and things like that. They collaborated with Miltos before and I think through their work together—because it was in the Netherlands—I got to know them a little bit. My parents were living in San Francisco for a year and Miltos had opened this place called Electronic Orphanage [in Los Angeles]. I was in California and Miltos had noticed my work online and he said, “Oh, you're very Neen,” and I didn't know what that meant. But I saw his work and I was very intrigued. I was very fascinated with the idea of using computers as subject matter in fine art, in painting. I’ve always loved computers, but you just didn’t see that in galleries. It was another world. I like this merging of worlds and this idea of, we would paint still lifes in the seventeenth century, and then what does the “still-life” mean now. There were a few very sharp and important ideas to me.

That was one of the ideas, and the other idea was treating the internet as a space and not as a tool. I found that very interesting. He said my work is Neen, but I made work before I knew about Neen. It wasn’t like Neen arrived and I changed, I was part of it before I knew about it.

It was very interesting seeing people take on media art from more of a personal perspective, because media art to me up until then, seemed like testing the material and stretching the material as far as you could, and it was also a little bit critical. Neen was more, “this is how I feel, so I’m going to make a work about that. That to me was the key difference between net art, glitch art, and this. I also really remember that art online was always a lot of small, fine things. Like little glitches and things, and I wanted to make bigger gestures. To me, net art felt like a swarm of mosquitoes and I wanted to make an elephant. That difference. But a purple elephant. Something.

He had the space in the Los Angeles and he said, “Why don't you come over and do a show?” That was the first exhibition I ever did. I think I was nineteen or twenty. He had seen one work, and I made another work for the show. I really liked the idea of the Electronic Orphanage. It was a place for people without a home; his idea of all these lost artists who go around with their laptop without a place to go because the art world was not really there for them. The commercial world is luring them because they’re so tech savvy, but that’s not where they belong. And the premise was interesting, that it was a gallery space that had a window façade and it was painted all black except the back wall. And the back wall would be projected on for exhibitions, but that was it. You were not allowed to have objects in the exhibition. He wanted the space to behave like a screen.

That was another idea that I thought was interesting. You had Chung King Road in LA, which had a lot of galleries and all the galleries at the same time would have an opening. It was massive and everybody, of course, was trying to sell stuff. And this was just ... the gallery’s a screen, you weren’t even allowed inside. The doors were closed and you just see the work. Artists were allowed to work there, but you weren’t allowed to leave any objects.

Rafaël Rozendaal, whitetrash.nl, 2001. Collection of JODI.

All these ideas now seem pretty straight forward. It doesn’t sound crazy, but at the time that was very different. Because it was always the idea if you make works for the screen, but then when you enter the space, you have to consider the space. So you have to make media art installations. But he’s like, “No, let's just show a website as a website.” And it will just behave like a website.

I met Miltos and it was very exciting because we both had similar things we were thinking about. It was very interesting to talk about—he had a lot of connections from the art world. I was at a dinner with Yvonne Force who was part of the funded naming of Neen, which was so expensive. We had a dinner and I had never been to these kind of dinners where they say, “You’re sitting here, you’re sitting there.”

Farrah Fawcett was there. And Farrah Fawcett was there because Art Production Fund was this fund that would make artist’s dreams happen. That’s kind of their premise. So they made Vanessa Beecroft’s first big show. They did things with the Beastie Boys. That kind of impossible thing. I think the nineties had a lot of room for ambitious projects, that were not sellable. Jeremy Blake was there with Theresa Duncan. There was another sculptor there. Farrah Fawcett was there because this sculptor, they asked him, “What’s your dream?” And he said, “My dream is to meet Farrah Fawcett and make art about her.” And they met and they fell in love. For the rest of his career, he just made sculptures of Farrah Fawcett. So she was there.

The reason I was there was I had made this website with my face and you could click on the different parts of my face and you would see different mustaches, different glasses, and different hair cuts. Very almost adolescent humor. And I made a fart website. I was kind of giggling that I was in this restaurant in Beverly Hills for that reason.

I remember people were at the dinner were like, “Oh yeah, I saw your work. I thought it was an ironic take on online culture.” It was online culture, but it wasn’t an ironic gesture.

It was a very exciting time meeting everybody from Neen. I felt like I had met a lot of people before and I was aware of the work of people like JODI, which I thought was interesting, but I didn’t really feel at home. It was a bit too much focus on technology for me, and I wouldn’t feel at home. Neen was a group of people. It really is something between net.art, and then later social media. This was somewhere in between. It was pre-social media, but it was very personal.

I remember everybody’s homepage. The members of Neen didn’t all agree on this, but almost everybody had a photo of themselves on their homepage. Which is something you would do back then. But net.artists wouldn’t do that, it was all very anonymous. I think we were very much about using the internet to express yourself, to publish yourself. To me, it always felt like the internet was about uploading yourself into different art works.

A sketch of Electronic Orphanage by Mai Ueda, 2001

LS: What about Electronic Orphanage? You had your first show there in 2001. Could you talk about both the show and the space itself?

RR: I made that piece with my face, which later on I traded with JODI. For me, the internet was a way of being myself. Because I felt like, in galleries you had to act very serious and I was eighteen, so I wasn’t so serious. Then for someone to say, “Oh, you belong here,” was a very good feeling, saying it’s okay to be like that. It was just a funny take on so many serious works in the art world about identity and revealing the self and we are many versions of ourselves. You can talk about that in very different ways. That piece was doing that in more of an online, silly way.

So I made that piece and Miltos said, “Oh, you should make a new piece.” Then I made the fart website, which, I mean, to make a fart website on the internet, okay, but then to put it in a gallery? Miltos had cache with the art world and people would stop by and they were clearly embarrassed. But out of respect for Miltos, they would keep being like, “Yes, very interesting.” So I found that very funny that they had to politely look at it, even though they knew. Up until to this day, I’ve hardly ever exhibited those works. After that, my work slowly went more towards abstraction. It was almost an adolescent art moment.

I also remember the opening was very packed. I really didn’t know much because this was before social media. So I couldn’t verify anything. This guy from out of nowhere with a webpage said, “You should come over.” I didn’t know if he was for real or not. I went on a Greyhound bus and I was like, “I hope there will be someone there.” I didn’t know. I was supposed to stay for a day and I ended up staying for a week and I hung out with a lot of people. It was very meaningful in a sense that there was a lot of things I was thinking about, he was a lot older and provided a lot of insight and experience. But the show itself, I didn’t know what Chung King Road was. It was so packed. Big surprise to see that happen. Yeah, it was great. I also really liked that I had e-mailed the works and there was no practical issue. I always tell people that if you start a gallery just buy a projector and then you have no expenses after that.

It was a really positive, interesting, and almost a transformative experience because I’d been making works online, but I wasn’t sure if that’s something you could expand upon. Miltos also came up with this idea of domain names and making domain names the title of the work and the location of the work. That was a very stimulating idea for me.

Electronic Orphanage, other than that, I think there were a lot of events every month, every month and a half, and I experienced those remotely online, but I wasn’t there until much later. It wasn’t like I was flying every week and keeping up with the scene. There was a time when it felt like there was a big crossover between disciplines. So there would be architects or designers or theorists or artists or video game makers or musicians and kind of blended in natural ways and I really liked that.

Aftermath of the crash at CascO.

LS: I was going to ask you about what happened after that at the Afterneen opening at CascO.

RR: Yeah, yeah. So what happened at CascO was, I was living in the Netherlands and CascO is in the Netherlands, and Miltos was waiting for his green card registration, so he couldn’t go to the Netherlands, so he said, “Why don’t you go, and why don’t you organize the show?” I had never organized a show before, so I just went over and said, hey, I’m going to fail. We started talking, and Andreas Angelidakis built the installation. I was sort of the bridge, because I was there. We made an installation and he made buildings based upon our personalities and our work. So he took one of my websites, which is clouds, and he made a cloud building. For Angelo Plessas, he made a rainbow building and interpretations to his work. I believe it was built in Second Life. You could walk around, ask questions, hang out there.

The gallery was basically a very long space on the canals in Utrecht and it was a glass façade just like the Electronic Orphanage. There were four computers and projection and you could wander in the space. Then there was a book space and an office area of the art space. There was a car here in the afternoon and the guy stepped on the gas to turn and get out of parking, but he lost control of the wheel somehow. He slammed into the gallery, which is not that wide. The car was almost as wide as the gallery. He ran over the installation and ran over the bookcase, which fell down. There was only one person working, but she broke her collarbone and her jaw. Imagine you’re just checking email and all of a sudden a car runs in.

There was always this weird stuff around, totally unexpected. But it was almost like a gesture between the physical, and the non-physical, it was a very strange moment.

LS: Very Neen.

RR: Yeah, when you think about glitch art, that’s really...

LS: Yeah, a physical manifestation of it, I would say. You also curated a show. The Neen Today show in Eindhoven in 2004. The concept of that was based off of Miltos’s FourFortyFour concept, so the exhibition was only open for sixty seconds, fully, right? Could you talk about that and explain the concept?

RR: The idea was that the space itself was that we wanted something experimental and not too formal. Not just works hanging on the wall. So I wanted to do this idea of a space where people make things, instead of a space where you present things. Since we’re all working on the computer, we had an apartment for a month, and we had this gallery space for a month. So people just came and went. Some people stayed for a week, and some people stayed for two weeks; we made works there. The idea of the minute was just the idea to focus everybody from one minute on being together—something that’s so opposite of online. I think the idea of being as much in the moment as possible. There was music and there was architecture by Andreas, and there were different websites projected, and bean bags so people could hang out and carpet floors so it felt homey, or more domestic, or more inviting than a cold space.

That, to me, also felt a little bit like the end of the completion of the whole project. I put a lot of work into it for half a year and also realized that curating is a lot of work. I think we had a big show after that in Milan, and then a book, and it kind of felt like a completion of the project. The hard thing with Neen was that it was maybe too ambitious with a launch at Gagosian, and a manifesto. Miltos was always stressing that it’s not a group, but it’s a movement, but for something to be a movement, you have to have people that come along.

Sometimes I feel like there were too many expectations. If it had just been, “Oh, this is just what we’re doing,” maybe that would have been more of a natural fit.

Neen Today, Eindhoven, 2004

LS: How much did being a part of Neen influence your personal practice or, do you think it kind of grew and developed alongside the project?

RR: Yes, for sure. To explain Neen in words is very hard, but part of it is that making things that don’t make too much sense. Because even when you’re an abstract painter, you’re still making sense because you have this history and trajectory and discourse and you can be like, “Well, I’m really into this material and I went to Yale,” and all this stuff. Even in the nonverbal area, there’s still a trajectory. But Neen was about incomplete thoughts, and I think the internet is also a place of incomplete thoughts and it formed me in the sense that I was always taught in school to gather lots of library items, to build your discourse, to build conversations and materials and make them connect, make them click into a complete finalized thing. With Neen, it felt like those niche, small interests on their own were better on their own than trying to make everything a cohesive mammoth project. I think even media art, you can have a tendency of explaining too much and saying this is here for that reason and this is here for that reason. This was more letting your interests be interest by themselves. That’s what it confirmed for me. I already felt that, and then working with this group of people it was like, “Yeah, it’s okay to do that.”

LS: Can you talk a little bit about Telic? Can you compare the two?

RR: I was not so into that idea. It was bit of categorizing things, almost a hierarchy way of thinking, which I was not so interested in. It was almost like a game that Miltos was playing, a provocation. Telic being the idea that things make more sense, are more goal-driven, are more oriented towards defining something and arriving at a logical conclusion. I’m not so interested in categorizing, I think it’s kind of dangerous. You agitate people, and then you want a reaction, but people just get annoyed and walk away. So, I don’t think that was the best side of Neen.

LS: Can we talk a little bit about the medium you used? There were a lot of works made by Neensters with Flash, especially with the Whitney Biennial project and the exhibitions.

RR: Yeah, that was the best tool at the time.

LS: Right.

RR: There were tons of tools. There was JavaScript, Shockwave, Director. There was Real Player. You had Chromeless Quicktime windows and the QuickTime plug-in. You had copy, paste, HTML, hacks. There was all kinds of ways in doing stuff. But for me, I want work to be scalable. That was really big...this idea of an elephant. It’s something that felt monumental and that’s something. Like for example, Processing. Everybody was excited about it, but if you would run Processing full size in the browser, it would crash. Flash was the best tool for what I wanted. It was a nice moment where programming was pretty accessible. Very rudimentary programming. You could just make a few buttons and you could draw on them. Everything else outside of that was much more complicated. It’s almost like the Snapchat of the time.

There’s legacy problems now. So my programmer is re-coding most of them. Now that there’s so much more possible with JavaScript and drawing objects on HTML and all these things that weren’t possible at the time. It’s just the best tool. Every other plug-in that I knew crashed a lot and doing things in JavaScript was hard to make scalable and was hard to do cross browser, there were a lot of cross browser issues. Things are much more standardized now. It just felt like the best tool. I never thought of the political implications of using a proprietary tool. I was just using my computer and was like, “Okay, this works best.” That’s it.

I remember people mentioning, “Oh, shouldn’t you use open source?” I hadn’t even thought about it.

LS: Would you say Neen is a word or concept is still useful? Or is it something that people still refer to and you see it as a completed project at this point?

RR: I see it as a completed project. I think Neen was something only the participants understood and will also only understand. So in that sense, the word is not even needed. It seems now if I look at historians contextualizing history of net art, it’s very easy to go from net art to social media-based practice. It seems like, “Okay, we had the web and then we have social media.” Neen is this weird thing in between that’s very hard to explain. The point was to be hard to explain. The weirdest thing to me was $100,000 was spent on the creation of a word and they didn’t even get the .com, at the time. So, in terms of history of branding, that’s really weird. Then they had the .org. Art Production Fund had the .org and they lost the password so they couldn’t extend the .org, so they lost that, as well. That’s kind of symbolic that it existed for a moment in time and it’s okay that it went away.

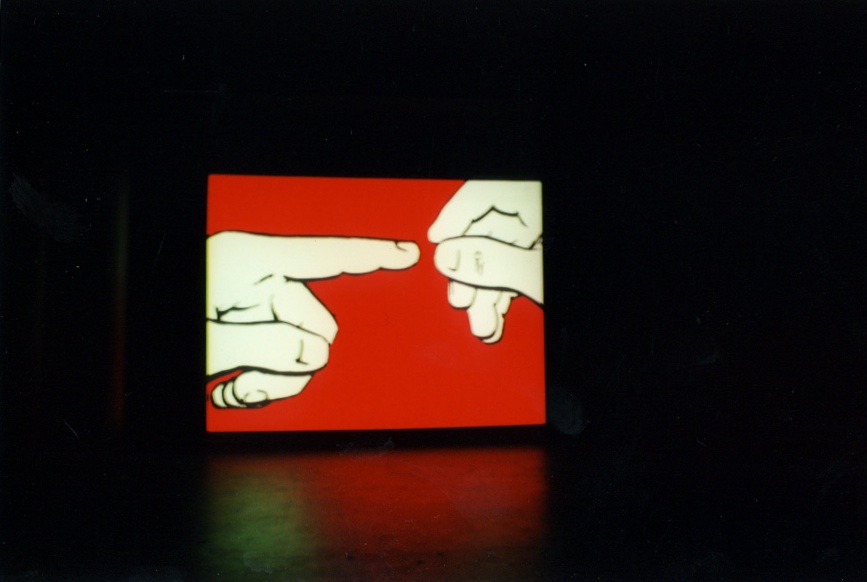

Rafaël Rozendaal, mrnicehands.com, 2002 Electronic Orphanage exhibition

LS: Do you see any sort of Neen’s legacy in work being created today through digital means?

RR: No, I don't think so. I know a lot of artists who are nervous about being copied and I never had that feeling that I was being copied too much. I felt like the work was very personal so it doesn’t make much sense. I think I always feel like I’m very much on my own. And that’s a good thing and a bad thing. For example, in the work of JODI I can see a lot more branches on that tree. I don’t think it was influential in that sense. For me, Neen was just a nod of the head that it was okay to continue in my direction. And that was very important.

It was very fun. I have to say that. After a while, there was a bit of jealousy or rivalry and things like gossip, but the first five years it was very fun. With these weird accidents and weird people you get to know.