This essay accompanies the presentation of Yael Kanarek’s World of Awe: The Traveler’s Journal (Chapter 1: Forever) as a part of the online exhibition Net Art Anthology.

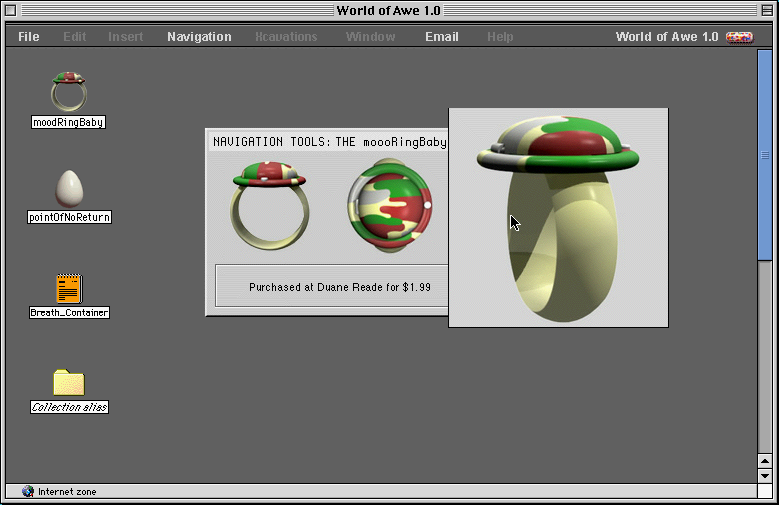

In 1995, Yael Kanarek began World of Awe: The Traveler’s Journal, a multi-part work detailing an anonymous traveler’s epistolary ruminations in Sunset/Sunrise, a desert found through a portal on 419 East 6th Street in Manhattan. Exhibited in the 2002 Whitney Biennial, the first chapter of the piece, titled Forever and created in 2000, uses a non-linear narrative structure, presenting a series of love letters and journal entries that describe regions like Silicon Canyon, “a dumpyard for all the hardware and software ever created,” and accounts of strange fictional technologies the traveler carries with them like moooRingBaby, a ring purchased for $1.99 at Duane Reade that speaks in expletives. World of Awe: The Traveler’s Journal (Chapter 1: Forever) uses a graphical user interface that acts as salvaged hard drive content from a laptop built by the protagonist. Narratively, the piece is driven by the Traveler’s desire for a nameless, lost treasure, the specifics of which are unknown to both the narrator and viewer alike.

What is most distinct throughout Chapter 1 is perhaps not its exploration of technology on its own terms, but rather Kanarek’s use of the desert landscape as the setting for the Traveler’s exhaustive yearning for intimacy. Kanarek’s work benefits from being read through theorist and anthropologist Elizabeth Povinelli’s theorizations on the Desert and intimacy in Geontologies: A Requiem to Late Liberalism and The Empire of Love: Toward a Theory of Intimacy, Genealogy, and Carnality. Povinelli’s viewpoints might assist the viewer in understanding the Traveler’s political and social existence in New York as impossible to execute in Sunset/Sunrise. Povinelli’s writing applied to Kanarek illuminates creeds of a liberal society that vitalizes itself through adherence to orders of liberal governance. Within these parameters, irregular affects and environments necessitate a larger technological solutionism and intervention to maintain their rhythm. Kanarek prefaces most of the Traveler’s journal entries with windows containing renderings of landscapes from Sunset/Sunrise: aerial perspectives of orange canyons, mosaics of weathered, eroded rock lacking any trace of water––though the homepage for the work states that in the Traveler’s journey, “an algorithm represses thirst.” Despite transcending this biological necessity, the Traveler’s situation in Sunset/Sunrise is ultimately distressing, complicated by the specific nature of the Desert as well as their separation from the subject of their love letters.

Yael Kanarek, World of Awe: The Traveler's Journal (Chapter 1: Forever), 2000. Screenshot created in EaaS using IE4.5 for Mac.

Throughout the work, it’s difficult to locate the Traveler amongst conventional place-markers, buildings, and landmarks. Most descriptions of settings articulate the overwhelming emptiness of the territory they occupy and travel through. This terrain, the Desert, in Povinelli’s formulation, is an affective tool that can explore how the non-living evokes panic amongst the living. The Desert undoes the dissimulation that life will always be life by failing to be immune from biological processes and the immanent conclusions of resource extraction.

Povinelli writes that “[the Desert] stands for all things perceived and conceived as denuded of life—and, by implication, all things that could, with the correct deployment of technological expertise or proper stewardship, be (re)made hospitable to life.” In the narrator’s only detailed account of Silicon Canyon under the “Navigation” part of the toolbar, we learn that though it is devoid of life or discernable political structure, the vast quantity of technological detritus amongst organic life indicates that Sunset/Sunrise may have once been grounds on which a civilization existed. Silicon Canyon––functioning as a metonym for the larger technocratic project that always already views barren terrain as a prospective blank slate for liberal governance and processes of dispossession––also exemplifies the crisis that modern “development” projects are always tied up with extinction, depletion, and negation. Povinelli, again: “The Desert is also glimpsed in both the geological category of the fossil insofar as we consider fossils to have once been charged with life, to have lost that life, but as a form of fuel can provide the conditions for a specific form of life—contemporary, hypermodern, informationalized capital.” If the abandoned technologies can operate as a kind of fossil, it is by this recuperative logic (referred to as the Carbon Imaginary by Povinelli) that the narrator––amazed and overjoyed by the forgotten processors, hard drives and monitors––constructs a laptop in an attempt to find the treasure, despite its seeming impossibility to be located.

In addition to finding the treasure, the other driving plot mechanism in Chapter 1 is a series of love letters to another anonymous character, often addressed simply as “beloved.” Though impossible to be sent or received, the letters (sometimes poetic, sometimes detailing the journey and searching) permeate with yearning and loneliness. Despite their only function as temporary relief, these letters in the work convey the Traveler’s anxieties, delineating a larger social anomaly wherein the Traveler’s former existence in New York prevents them from projecting liberal fantasies of vitalization onto the Desert. Instead, though written from Sunset/Sunrise, the letters reveal the Traveler’s continuing identification with and function within the city they departed.

Modern forms of intimacy “secure the self-evident good of social institutions, social distributions of life and death, and social responsibilities for these institutions and distributions.” Thus, there’s a symbiotic relationship between the domestic and cultural practices of the intimate couple and the larger necropolitical state apparatus. Both the independent and intimate subject, while disparate, are both symptoms and constitutive events of contractual forms of recognition within structural power. Specifically, the intimate and genealogical subject seeks to make themselves more coherent and legible by engaging in politics of visibility, entrusting the State as an alleged ally through apparatuses like marriage.

In the case of the narrator in Sunset/Sunrise, this specific mode of discipline is thrown into crisis, particularly as they are situated in the Desert environment that would otherwise be productive for genealogical action and realization (colonization, creating kin). In other words, the Traveler is upset by the impossibility of existing within liberal social order as they did prior to being in Sunset/Sunrise. At such an impasse, of course most of the love letters discuss the lost treasure with bleak obsession, a distraction from existing in political paradox. From “Love Letter 37/5”: “I’ve been surrounded by dark evenness for a while now. Wherever I turn I encounter sameness. Even when I assume to see or sense a structure it appears the same in any direction I turn.” The desire for structure, or the normative trajectories of existing intimately as it pertains to paradigmatic cultural function, is sought but never found.

Yael Kanarek, World of Awe: The Traveler's Journal (Chapter 1: Forever), 2000. Screenshot created in EaaS using IE4.5 for Mac.

Through the narrator’s constant enunciations of desire, they cloud their own memory, noted throughout part of their travel log. Textually, what appears as mere separation anxiety is also the narrator’s excesses of memory overflowing. They fail to exist in a state of both personal and historical amnesia as they once did, wherein memory loss is a perennial symptom and constitutive event of liberal society’s production. Povinelli states that “intimate recognition establish[es] a new subject out of the husk of the old and reset the clock of the subject at zero.” If normative love and intimacy maintain the orders and addresses of these organizing schemas, then the narrator’s newfound loneliness forecloses on the possibility to start over, to achieve the privilege of resetting the clock. Resigned to viewing themselves on their own terms without inter-subjective recognition, capitulating to “adapt or die” capitalist sentiment, the Traveler is left to locate themselves amongst a scattering of obsolete technologies.

In short, Sunset/Sunrise as the Desert provides the narrator with a shock powered by the excesses of existing outside of traditional economies, social paradigms, and capital flows that are centered by the intimate couple they once existed within. By lacking potential for functioning intimately but possessing an excess of the individual personhood, they are left with an ultimately useless, double-binding self-determination. Technology—often by projecting onto an imagined void like the Desert that necessitates its own use—determines its own fraught ontology in the same way. In the feedback loop of the lonely narrator and electronically wired paths and deserts in Chapter 1 of World of Awe, Kanarek demonstrates that modernity’s sick obsession with extraction, vitality, and extinction makes Sunset/Sunrise appear as a likely future.